Introduction – The Ancient War Machine

In a conventional sense, when we talk about the ancient Assyrians, our notions pertain mostly to what is known as the Neo-Assyrian Empire (or the Late Empire) which ruled the largest empire of the world up till that time, roughly existing from a period of 900-612 BC. Known for its utter ruthlessness and effective military system, this is what historian Simon Anglim said about the ancient state of the ascendant Assyrians –

…an aggressive, murderously vindictive regime supported by a magnificent and successful war machine. As with the German army of World War II, the Assyrian army was the most technologically and doctrinally advanced of its day and was a model for others for generations afterwards. The Assyrians were the first to make extensive use of iron weaponry [and] not only were iron weapons superior to bronze, but could be mass-produced, allowing the equipping of very large armies indeed.

But unlike the supporters of Nazi Germany, the Assyrians were arguably more ‘progressive’ in their political institutions. While having the tendency to deport a large number of people, they believed in the collective nature of being Assyrian (a ‘title’ given even to the conquered people under their dominion). In essence, they didn’t believe in nonsensical entities like ‘master race’; rather the later Assyrian rulers looked at every subject as a potential military/economic resource integral to the empire.

Moreover, the Assyrian state existed for long before its final culmination into the magnificent Neo-Assyrian Empire. In fact, according to most historians, their capital city of Ashur was founded sometime in the 3rd millennium BC, thus being even older (by centuries) than the great Babylonian king Hammurabi and his code. So without further ado, let us take a gander at the fascinating history of ancient Assyria and the incredible Assyrian army (military system).

Contents

- Introduction – The Ancient War Machine

- The Assyrian Paradox

- War – The Great Economic System of the Assyrians

- The Assyrian King Embodied Ultimate Power

- The ‘Rightful’ Policy of Frightfulness

- The Imperial Political Moves

- From Summer Service to a Professional Standing Army

- Chariots – The Shock War Machines of the Ancient World

- The Shield and Archer System of the Assyrian Army

- Proficiency in Siege Warfare

- Honorable Mention – Inflated Skins for Swimming

The Assyrian Paradox

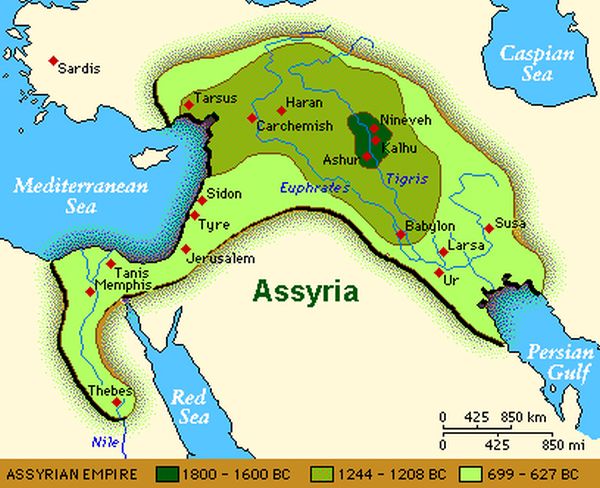

During their zenith from the 10th century BC to the 7th century BC, the Assyrians controlled an enormous territory that extended from the borders of Egypt to the eastern highlands of Iran. Many historians perceive Assyria to be among the first ‘superpowers’ of the ancient world.

In a brilliant insight by historian Mark Healy, quite paradoxically, the rise of Assyrian militarism and imperialism (from the 15th century BC) mirrored their land’s initial vulnerability, as it lay inside the rough triangle defined between the cities of Nineveh, Ashur, and Arbil (all in northern Mesopotamia).

Simply put, this terrain rich in its plump grainlands was open to plunder from most sides, with potential risks being posed by the nomadic tribes, hill folks, and even proximate competing powers. This, in turn, affected a reactionary measure in the Assyrian society – that led to the development of an effective and well-organized military system that could cope with the constant state of aggression, conflicts, and raids (much like the Romans).

Such an intrinsic scope of the military being tied to the economic well-being of a state resulted in what can be called a domino effect. So in a sense, while the Assyrians formulated their “attack is the best defense” strategies, the nearby states became more war-like, thus adding to the list of enemies for the Assyrian army to conquer.

Consequently, when the Assyrians went on a war footing, their military was able to absorb more ideas from foreign powers, which led to even more evolution and flexibility (again much like the later Romans). These tendencies of flexibility, discipline, and incredible fighting skills became the hallmark of the Assyrian army that triumphed over most of the powerful Mesopotamian kingdoms in Asia by the 8th century BC.

War – The Great Economic System of the Assyrians

As we discussed before, the scope of Assyrian military development and expansion was intrinsically tied to the economic prosperity of the rising realm. In the period circa 1450 BC, such a military system was required to actually protect the vulnerability of the Assyrian lands locked between the powerful Mesopotamian states of Mitanni in the north and Babylonia in the south, which supported the land’s economic stability. But as the centuries went by, Assyria morphed into the aggressor with the aid of its continually developing military prowess.

Suffice it to say, more conquered lands brought more plunder in the form of various valuable resources, ranging from metals, and horses to skill-based populations. This was complemented by the control of crucial trade routes that crisscrossed through various parts of Mesopotamia.

In essence, waging wars (along with conquering and raiding) became organized ventures conducted for the betterment of the Assyrian realm’s economy. So simply put, by the 11th century BC, the security needs of the state became indistinguishable from the prosperity of the ascending empire – with the Assyrian army playing its crucial role in both the ‘merged’ affairs.

The Assyrian King Embodied Ultimate Power

As warfare became an organized economic activity of Assyria, the realm’s militarism was epitomized by its ruler. In other words, when the kingdom evolved into a burgeoning empire, the scope of expansionism was mirrored by ideological values (since economic prosperity alone was not enough in enticing a growing populace).

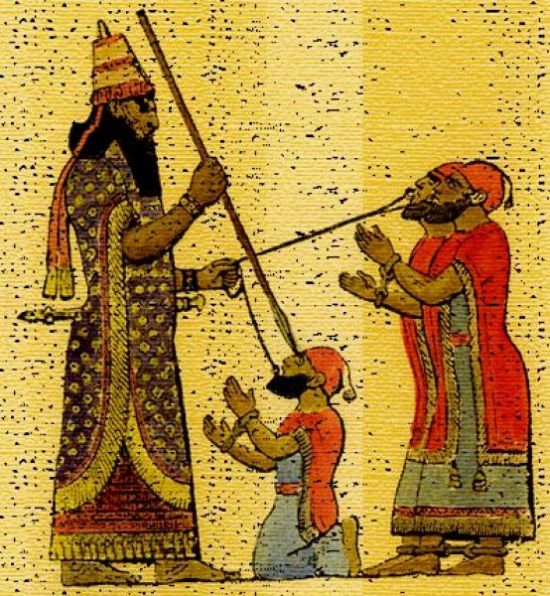

Such theological/nationalistic tendencies to associate war with glory became a cornerstone policy for the political elite of Assyria, with the king taking center stage in war-based policies. The Mesopotamian god Ashur was the head of the Assyrian pantheon, and hence every decision made by the ruler was taken under the symbolic ‘validation’ of Ashur – ranging from plundering, massacres to even domestic policies.

So in many ways, the Assyrian state (along with its power and policies) was espoused by its king. This meant that the Assyrian ruler had to take up multiple roles – like acting as Ashur’s earthly ‘agent’, proving himself as a capable commander-in-chief of the Assyrian army, and also taking part in domestic and political affairs.

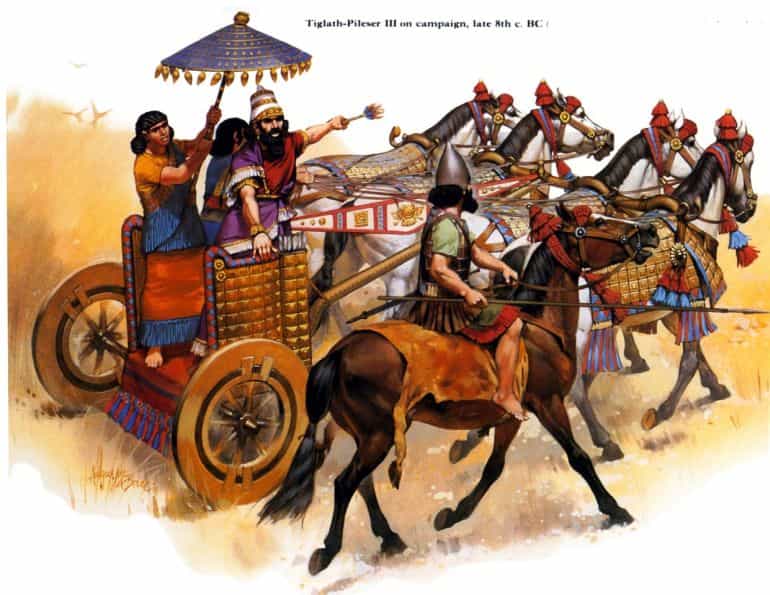

Such a stringently centralized structure of administration and politics was advantageous to dynamic rulers like Tiglath Pileser III, Sargon II, and Sennacherib. But on the other side of the coin, it also made the Assyrian state overtly dependent on its king. Consequently, a weak ruler usually mirrored the ‘bad times’ faced by the empire.

The ‘Rightful’ Policy of Frightfulness

In an example of Assyrian annals in the 9th century BC, the 7th campaign of King Ashurnasirpal II had been described in full and gory detail. The keywords in these official records often contained phrases like ‘massacred’, ‘razed’, ‘destroyed’, ‘burned’, ‘felled with the sword’, and ‘erected them (alive people) on stakes’.

Now while these words concoct imagery of savagery and sadism (which actually might have been the truth in some cases), there was more to the scope of Assyrian brutality than sheer terror. In fact, according to historical pieces of evidence, most of these punitive campaigns were usually conducted for mitigating rebellions that fumed around corners of Assyria. So in a sense, the very nature of these brutal actions and punishments acted as a counter to the restlessness (and apparent disorganized scope) of the rebels and potential rebels.

In other words, the policy of frightfulness was employed as a psychological measure that would ‘discipline’ the rebellious Assyrian (and other clients) subjects – a military strategy also used by the Mongols on their opponents. To that end, such terrors were inflicted as intentional ‘calculated’ ploys by the king and his loyal commanders.

Moreover, if we go the route of Assyrian annalistic traditions, the punishments were specially selected and only employed in chosen circumstances. But when they were indeed inflicted, the savage actions were fully ‘advertised’ so as to serve as reminders to the future rebels and proximate powers.

The Imperial Political Moves

By the first half of the 8th century BC (from around 811-745 BC), the Assyrian empire delved into political turmoil with many provincial governors gaining more power and virtually declaring their autonomy from the traditionally centralized state.

But the ascendancy of King Tiglath-Pileser III changed it all, with a flourishing period of rigorous political and administrative reformation. One of his first orders of business was to break down the areas (and thus populations) encompassed by each province into smaller administrative units.

Simply put, such measures were approved to fully undermine the power of the provincial nobles and political elites. However, the dynamic Tiglath Pileser didn’t just stop at reducing their territorial integrity.

He also took the seemingly desperate approach that would inherently curb the power of the nobles in future scenarios – by employing ‘sha reshe‘ or eunuchs as state-monitored governors of many such administrative units spread across the empire. Such drastic steps made sure that the disgruntled descendants of many elites couldn’t access their power base, while at the same time reinforcing the loyalty of the state-employed eunuch.

From Summer Service to a Professional Standing Army

Beyond the political and administrative realms, Tiglath-Pileser III was also known for reforming the much-touted Assyrian army. In the period between the 14th century to the early 8th century, the army was mainly drawn from the native peasant population.

In that regard, the military had to follow the dictates of seasonal campaigning, since most farmers were occupied throughout the spring and early summer. So only by July, the annual call-ups were generally made; and thus campaigns, invasions, and even raids were ‘adjusted’ in accordance with the yearly agricultural timetable.

Suffice it to say, this mustering system was inflexible due to a lot of seasonal variables. But Tiglath-Pileser traversed the whims of nature by creating an entire standing army known as ‘kisir sharruti‘. In other words, his army (or at least most of the manpower) was available to him throughout the year, with a strict recruitment policy being imposed from the native provinces.

This was supplemented by tributes in the form of manpower from the proximate vassals along with mercenaries, thus transforming the national Assyrian army into a diverse bunch.

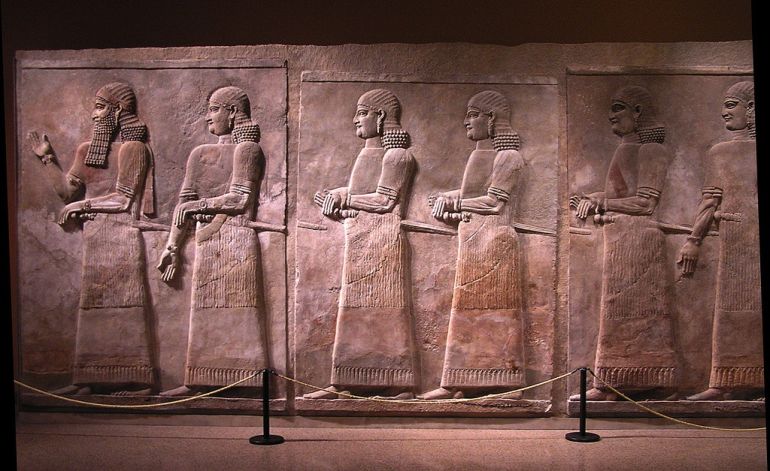

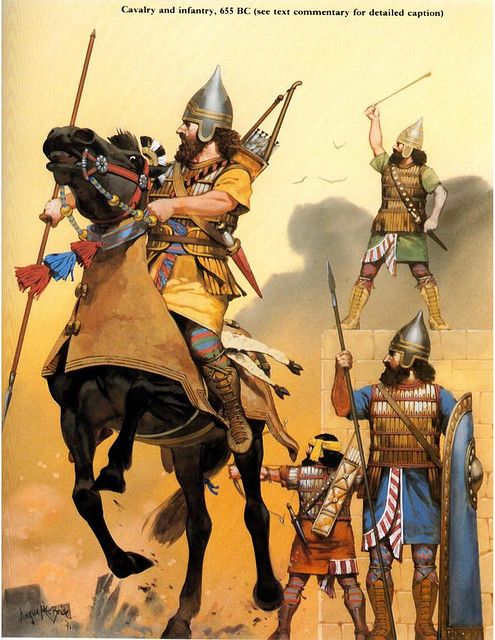

However, in spite of such diversity, the Assyrians were probably among the first factions in history to make use of uniformed appearances for their military forces. Beyond tactical advantages, the element of uniformity in armor types and arms was possibly utilized to endow a ‘nationalistic’ flair to the empire’s army. These factors, in turn, led to the momentous creation of well-equipped armed forces that were the ancient precursors to modern-day professional armies.

Chariots – The Shock War Machines of the Ancient World

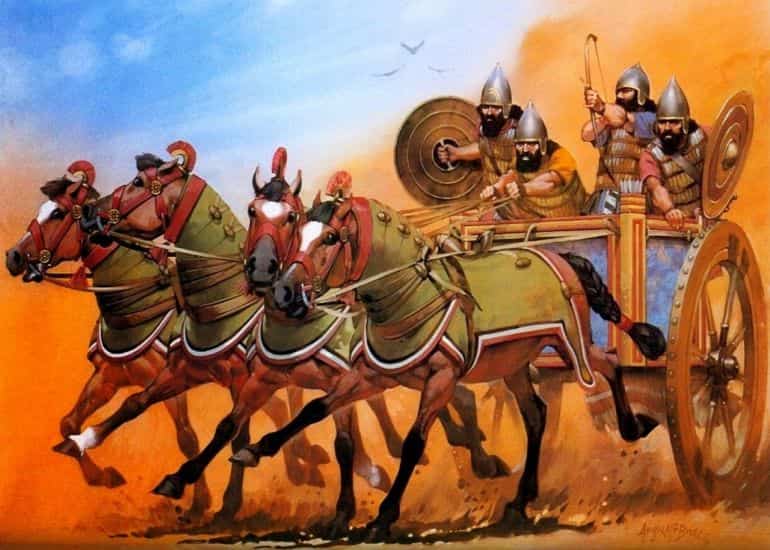

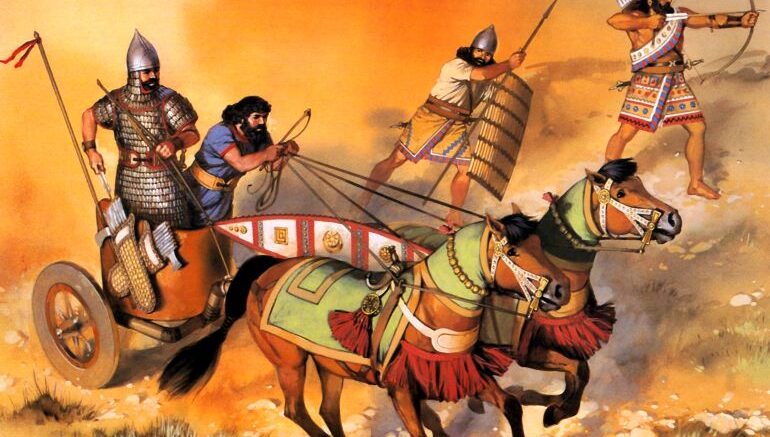

Historically, chariots have often been relegated to anachronistic traditions among Bronze Age civilizations. In the Assyrian army, however, chariots took a special place among the royal family and their wealthy retainers – as is evidenced by their continuous use on the battlefield for over a millennium.

In fact, by the time of Ashurbanipal in the late 7th century BC, the chariot morphed from a flexible platform of archery and reconnaissance into a heavy, boisterous instrument of war drawn by four horses and mounted by four men.

So in many ways, the chariot was designed as the ultimate shock weapon that after serving as a mobile missile platform, would charge into the enemy ranks with its imposingly sturdy frame. The impact, like the later charges of the medieval knights, would have both psychologically and physically afflicted the enemy.

However, the chariot also had shortcomings in the scope of flexibility, especially in uneven terrain. This is where the trained cavalry forces of the Assyrians came into the fray. On the battlefield, they were used to exploit and then drive home the charge that was initially carried forth by the heavy chariots.

Such grand maneuvers were complemented by other crucial activities like surveillance and flanking. Interestingly, one of the tactical units of the Assyrian army pertained to the pairing of two horsemen, where one rider held the reins of the other horse while his ‘partner’ rider shot his bow. Tiglath-Pileser III’s army reforms retained such a pairing tactic, but the horse archers were gradually replaced by dual lancers.

Over time the economic advantage of cavalry forces over chariots became much evident, and as such the Assyrians began to treat horses as valuable resources. In fact, by the 9th century BC, many of their wars and raids were targeted towards acquiring lands with proven horse-breeding pedigree, like Medes. Furthermore, horse supply lines within the empire were micromanaged at the provincial level with specialized officials employed for the task.

The Shield and Archer System of the Assyrian Army

In the previous entry, we talked about the pairing system of horsemen that allowed them to function as a tactical team on the battlefield. But beyond elite chariots and cavalry forces, the bulk of the Assyrian army was formed of infantrymen. Given the Assyrian penchant for organizational capacity, the infantry must have been grouped into specific formations – each with its own set of tactical values.

To that end, the Assyrians also employed the pairing system when it came to their often vulnerable archers. In ancient times, some cultures valued the skill of archery, and so its predominance as an offensive arm of the Assyrian army was ingrained in their military doctrines.

The Assyrians further developed this ambit by employing a dedicated spear bearer who accompanied the archer. So while the archer reloaded his bow, the spearman was responsible for protecting his partner (a formation type also encountered in the later Persian Achaemenid armies).

The enormous shields (that were often higher than the men) are evidently portrayed in the bas-reliefs from the time of Tiglath-Pileser. According to contemporary records, these shields were apparently made of thick plaited reeds. And once again harking back to the organizational skill of the Assyrians, there were specially allotted river beds that were chosen for growing the reeds (to be used specifically in the large, protective shields).

Proficiency in Siege Warfare

Neo-Assyrians were also known for another element of warfare, and it entailed their dedicated approach to sieges. By the 8th century BC, most of the major commercial centers and settlements of Mesopotamia and nearby lands were walled. And that is when the experimentation of the Assyrian army reached its heights with the deployment of various siege towers and machines.

For example, the Lachish wall relief that portrays Sennacherib’s siege in 701 BC, clearly showcases wheeled engines draped in thick leather skins. These massive constructs were arrayed and pushed to the walls of the city with the help of specially made tracks (that were supported on previously built earth ramparts outside the city wall, by the siege engineers). The Assyrian objective mainly entailed bringing these humongous siege engines close to the wall where they could batter the defenses with the help of ‘built-in’ ramming rods.

Suffice it to say, there was an Assyrian method to the madness when it came to advanced siegecraft. But as historian Mark Healy noted (in his book The Ancient Assyrians), the Assyrians were not always ‘comfortable’ with siege warfare; and their first choice traditionally harked back to disciplined yet flexible maneuvers on open battlefields. In that regard, it can be argued that the policies of terrorizing and frightfulness might have been used as ‘solutions’ that broke the morale of the enemies before it even came to the final stage of defensive siege warfare.

Honorable Mention – Inflated Skins for Swimming

The Assyrian military ingenuity, however, didn’t stop at mixed cavalry forces and incredible siege crafts. One particular bas-relief aptly showcases how the Assyrian army (probably the ones assaulting from the riverfront) was provided with specially designed goatskin bags that could be inflated and then used to ferry across the water, with the horses tethered and guided behind them.

In a similar manner, their enormous war machines were basically modular in design. So these engines and towers could be dismantled and tied to specially devised marine crafts made of skin and easily hauled across rivers, to be later assembled outside the city walls. And we stretch the scope a bit, there are also references to scuba diving in ancient Assyria, as is represented in a 3000-year-old fresco that shows men swimming underwater, using some kind of breathing device.

Book References: The Ancient Assyrians (By Mark Healy) / The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy (By Mario Liverani)

Online Sources: Livius / Aina / Fordham University / Academia

Featured Image: Illustration by Angus McBride

Be the first to comment on "Assyrians: The ‘Ruthless’ Superpower of the Ancient World"