Often viewed as the working-class heroes of Roman society, the gladiators (derived from Latin gladiatores) have surely seen their fair share of screen time in our modern-day popular media. However, beyond grand spectacles and bloody feats, the very nature of gladiatorial contests alluded to the ‘institutionalization of violence‘ ingrained in Roman society since its tribal days. So, without further ado, let us take a gander at the origins and history of the Roman gladiators that go beyond the realm of glitzy fiction to account for brutal reality.

Contents

- Munera – the Funerary Contests That Gave Way to Gladiatorial Combats

- A Mishap that Supposedly Killed 50,000 People!

- The Hoplomachi – Professional Gladiators of the Day

- A Paradox of Low Class and High Fame

- ‘We Who Are About To Die’

- ‘ Uri, vinciri,verberari, ferroque necari ’ – The Oath of the Gladiators

- Safety Measures Backed by Precise Diets

- Ostentatious Armor and Bending of Rules

- A Theater of Blood Lust, as Opposed to Chaotic Fighting

- The Naumachia – ‘Gladiatorial’ Ship Combat

- The Chances of Survival of a Gladiator

- Rudis – the Symbolic Wooden Sword of ‘Freedom’

Munera – the Funerary Contests That Gave Way to Gladiatorial Combats

In what might have been the precursor to latter-day gladiatorial combats, a nobleman named Brutus Pera made his death wish in 264 BC that his two sons should pay for combats that were to take place in the marketplace to mark his funeral. In less than a hundred years, such contests became pretty commonplace, and the combatants were generally the slaves of the organizer – thus becoming the first gladiators.

In fact, in 174 BC, one of the munera (a ritualistic service dedicated to the dead) involved 74 men pitting against each other in a gruesome event that took place over three days. And as time went by, the munera expanded in scope to include spectacles like the venatio – which entailed the hunting of hundreds of exotic wild animals across the Roman lands by the trained venatores.

There was a symbolic side to this grisly affair, with the animals like lions, tigers, and other predators alluding to the savages and ‘barbarians’ of the world that mighty Rome had subjugated (interestingly enough, the Mongols also had a similar type of hunting ritual that involved the ‘tactical’ killing of innocent beasts).

And, as the Roman Republic grew in pomp and size, her nobles thought out newer and grander ways to commemorate their legacy – by even making provisions in their wills for such funeral contests. In essence, the funerary service became more of a political statement (combined with bloody spectacles) that supposedly espoused the greatness of the patrons.

As a result, being miserly regarding such ‘expected’ funeral games often incurred the displeasure of the common townsfolk. One particular incident aptly exemplifies such hedonistic attitudes – during the reign of Tiberius, a centurion’s funeral service was forcibly interrupted by the townspeople as they demanded funerary games. The situation soon turned into a riot, and the emperor had to send his troops to quell the disturbance.

A Mishap that Supposedly Killed 50,000 People!

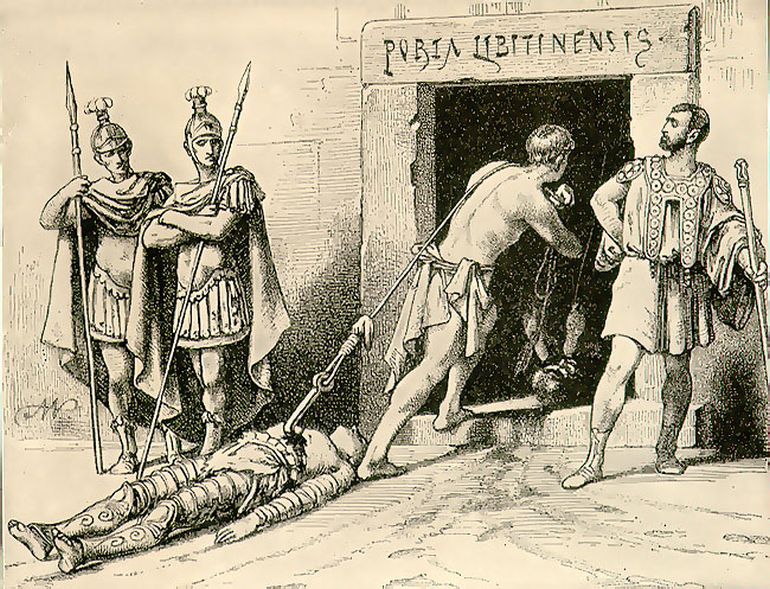

The popularity of such funeral contests among the ancient Romans increased exponentially – so much so that the patrons had to accommodate a variety of spectacles at specialized purpose-built venues, thus culminating in the final ‘evolution’ of gladiatorial games. These amphitheaters mostly sprung up inside Rome (the city) beside the Forum and were initially constructed from wood with sand floors.

In fact, the very word harena – meaning ‘sand’, gave way to the term arena. Suffice it to say, overcrowding was a major predicament for the engineers, and as such one of the accidental mishaps resulted in the collapse of the entire superstructure of an amphitheater at Fidenae.

According to Tacitus, the death toll reached over 50,000 people – which might have been an exaggeration on the author’s part but still hints at the massive surge of popularity of such gladiatorial contests that took hold across the Roman world.

The nature of the incredible demand for gladiatorial combats could also be measured by the actual number of amphitheaters inside the Roman-held lands. According to architect and archaeologist Jean-Claude Golvin, this figure accounted for 186 venues spread over the Roman-ruled realms, while being additionally complemented by 86 other possible locations that might have had some kind of arenas for gladiators and their bloody spectacles.

The Hoplomachi – Professional Gladiators of the Day

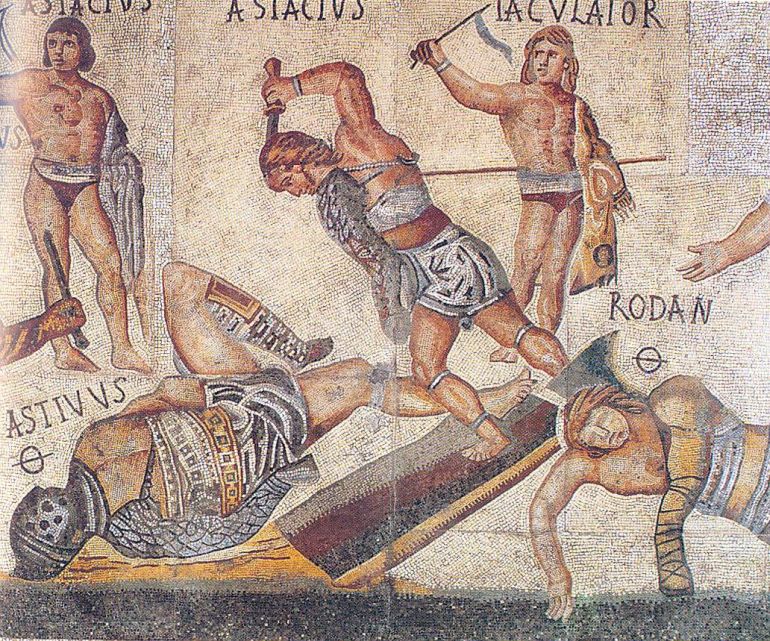

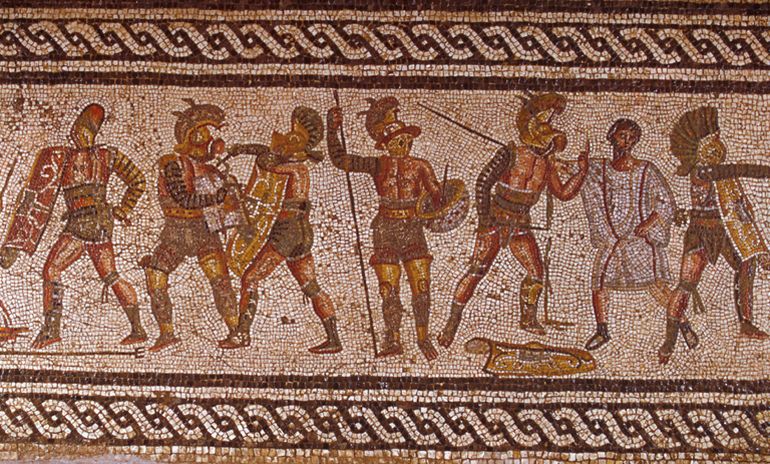

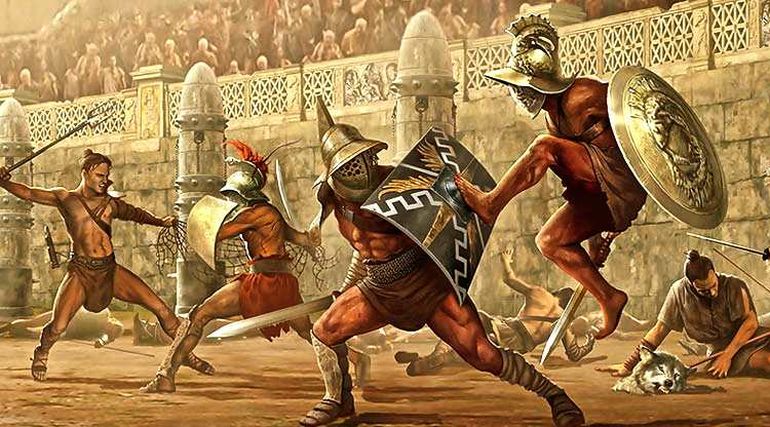

While the gladiatorial combats had their precursors in funerary contests fought among ill-equipped slaves, the spectacles at their gory zenith were ‘fueled’ by the professional warriors called hoplomachi (or armored fighting men – mostly inspired by the Greek hoplites) and their prowess inside the bloody arena.

To that end, these heavily armed men were the actual ‘gladiators’ that we are accustomed to seeing being depicted in popular movies and television programs. Skillful in handling their short sword (gladius) and round shield, the combatants were trained to ‘entertain’ the crowds whether it be in single combats or staged battles inside the arena.

Such forms of crowd-pleasing entertainment alluded to the spectacle of long-drawn conflict as opposed to quick bloody events. In that regard, the hoplomachi were experts in prolonging the suffering of their opponents which entailed the drawing of blood and its spilling onto the sand.

Simply put, they were a far cry from the ill-prepared criminals that went into the arena to die. Instead, they were viewed more as dashing daredevils, who while sharing some of their bad luck as being initially dispossessed, lived to please the rousing and often ruthless Roman spectators.

A Paradox of Low Class and High Fame

The question naturally arises – where did such professional gladiators come from? Well, in the majority of the cases, the men (and few women) were bought from thriving slave markets. Some of them were simply sold by their masters because of their past crimes or transgressions, while others were prisoners of war.

However, beyond the scope of dispossessed slaves and war victims, even free men joined the ranks of gladiators – some who had lost their inheritance and some who were simply addicted to the thrill of gladiator games, fighting and winning accolades from the crowds. According to modern estimations, around 20 percent of gladiators admitted into the ludi gladiatori (gladiatorial schools) were free men of Roman society.

And once the person was branded as a gladiator, he was seen as a social equivalent of a prostitute – with the term ‘gladiator’ even used as an abuse in various Roman circles. This directly contrasted with their fanfare and popularity among the citizens of the Imperial Era, especially during the grand gladiatorial spectacles that were akin to big sporting events of our modern world.

In fact, the fame and reputation of some famous gladiators reached such dizzying heights that their names appeared on city walls, while discussions about their victories and even sex appeal arose in inns, villas, palaces, and private dining rooms. And if discussions were not enough, the paradoxical adoration of gladiators took bizarre forms – with their oily grease, skin scrapings, and even blood (brushed with jewelry) being collected and sold to Roman women as aphrodisiacs and restorative potions.

‘We Who Are About To Die’

Till now, we had talked about the ‘professional’ side of gladiators, and how gladiatorial contests formed an integral part of a thriving business model that was intertwined with the political system of Rome. But beyond such glitz and glory, there were the other fighters who were basically forced into the arena to spill their own blood – in what can be termed as gladiatorial combat.

These were the noxii, the most condemned prisoners, criminals who were mainly accused of robbery, murder, and rape – and thus provided expendable ‘fighters’ whose sole purpose was to die inside the arenas, almost as a form of a grisly public execution that morphed into a sadistic ‘entertaining’ form.

After being shackled, shoved, and paraded inside such gladiatorial rings (especially during the afternoon shows) with jeering crowds clamoring for their blood, they had to make a grim proclamation before the Roman emperor – Ave Caesair, morituri te salutant! (We who are about to die, salute the Emperor).

After this statement, they became a part of the mass spectacle that sometimes involved a fight to the death till the last man was standing (or everyone was killed). However, at other times, the noxii were simply used as living props who were unarmored (or sometimes dressed in ‘show’ armor) and then declared as opponents against the adept postulati, veteran gladiators armed with maces.

Consequently, these famous gladiators made a gory demonstration of slowly dispatching the straggling criminals by spilling their blood on the sands of the arena. Once again, beyond just the Romans, such ‘mock’ gladiatorial combat (or execution) was also practiced in other warrior cultures, namely the Aztecs.

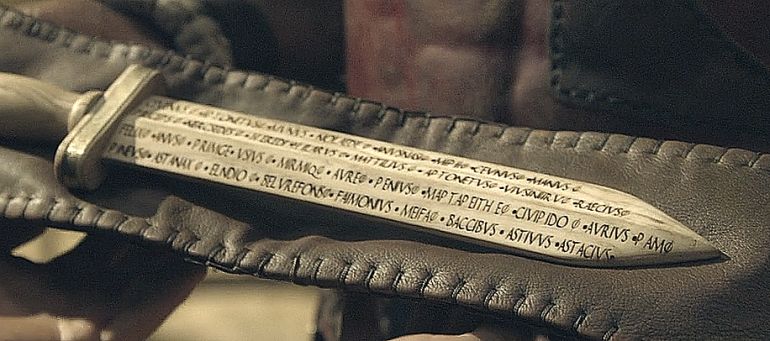

‘Uri, vinciri,verberari, ferroque necari’ – The Oath of the Gladiators

Now while the noxii class belonged to the lowest strata of the gladiatorial scope, the actual gladiators also had to endure hardships and adversity, as is exemplified by their sacramentum gladiatorium (oath of gladiators) – ‘Uri, vinciri,verberari, ferroque necari.‘ Roughly translating to – ‘I will endure, to be burned, to be bound, to be beaten, and to be killed by the sword’, the phrase had to be repeated by the men before their induction into the gladiatorial ambit.

After the utterance of these words, they were solemnly led to their tiny lockable cells that were spread around the perimeter of the gladiator training school and grounds – and thus their brutal lives as ‘dispensable’ showmen of Rome started. Fortunately, the free men who willingly accepted the dangerous career were still given an ‘opt-out’ opportunity where they had to pay a cash fee to the lanista (the trainer or manager of the acquired gladiators).

Suffice it to say, the balefully dangerous nature of frequent arena fighting (and the subsequent harsh lives inside the guarded barracks) took its toll on many a Roman gladiator, not only on the physical level but also on the psychological level. As a result, there were occasional incidences of suicide within their ranks, so much so – that even special guards kept vigilance to prevent such self-destructive activities that could potentially hamper the business of the lanista.

To that end, there was one incident of a Germanic gladiator self-choking on a sponge material. Another grisly scenario involved the apparent mass suicide of 29 Frankish prisoners, who had strangled each other while the last man standing smashed his head – before they could make their bloody debut inside the arena.

Safety Measures Backed by Precise Diets

As for those gladiators who continued to live, fight and emerge victoriously, had better chances of making a name for themselves in the affluent Roman circuits. Interestingly, such candidates were also taken care of by a specialized staff of the famous gladiator schools, thus mirroring our modern-day treatment of athletes and famous sportspeople.

For example, while the training schools themselves were guarded by fences and walls (so as to prevent ‘jailbreaks’), stringent safety measures were taken inside the premises. Such aspects included the prohibition of sharpened weapons in most cases, with wooden swords and substitutes being the favored training arms. Moreover, when an accidental injury occurred during training sessions, physicians rushed to the training school grounds to treat such wounds (with their medical equipment, like scalpels, hooks, and forceps).

Incredibly enough, the schools also employed specialized diet experts who dictated the food types and daily nutrient intake by the training gladiators – for their prolonged healthiness and defined muscular development. For example, sometimes gladiators were nicknamed the hordearii (‘barley men’), since the consumption of barley aided in mitigating the arteries with fat, thus preventing heavy bleeding that occurred through deep cuts and injuries.

Ostentatious Armor and Bending of Rules

While most armor systems were adopted by the different gladiatorial classes for their intrinsic practicality, there were also ornamental armor pieces that were only flaunted by the gladiators for their dramatic effect in crowd-packed venues. In fact, many of the armor sets donned by the gladiators evoked the imagery of Roman ‘enemies’.

Such stereotypical representations (like the British type, Samnite type, and Thracian type) added to the theatrical flair inside the arena where ordinary Romans could cheer and jeer at their favored factions. Later developments also incorporated various thematic styles with mythological and fantastical motifs – like the retiarius armed with his net and trident (like a stylized fisherman), who was often pitted against the murmillo with his ostentatious helmet (with a fish-shaped crest) and half-man half-fish attire.

Unfortunately, the status of most gladiators fighting in the arena was so low that they didn’t even have a say when it came to significant changing of rules in the grand contest events. These decisions and thematic alterations were usually made by the editor before the commencement of the gladiatorial match.

However, there were also times when the rules were unfairly exploited so as to give one gladiator-type advantage over the other. For example, it is commonly believed that Caligula intentionally made the murmillo gladiators reduce their armor because he favored their opponents – the Thracian-type gladiators, who had different fighting styles.

A Theater of Blood Lust, as Opposed to Chaotic Fighting

As we can gather from the thematic presentation of the different types of gladiators, the ambit of gladiatorial fights inside the arena did take a theatrical route, as opposed to practical combat. Some of us can visualize such gaudy yet bloody affairs from the scenes of the movie Gladiator (a fictional scope that otherwise was unhistorical in many respects).

To that end, the gladiators were not only dressed to look enticing and exotic, but the manner in which they fought sort of had a choreographic element to it that lengthened the scope of combat, instead of quick and effective dispatching of their opponents. But therein lay the paradoxical scope of such gladiator contests, where fantasy set-piece of Roman arenas played their part in entertaining the audiences, while the reality of deaths and severe injuries played their part in affecting the fighters.

The Naumachia – ‘Gladiatorial’ Ship Combat

Since we brought up the scope of fantastical elements, no spectacle exceeded the Roman penchant for grandeur and butchery than the naumachia (literally ‘naval combat’). Believed to be founded by Julius Caesar himself, the first of these massive engagements were conducted on a specially dug lake by the Field of Mars (in Rome).

When this lake was filled with water, the entire area could easily hold 16 large war galleys manned by over 4,000 oarsmen. And aboard these huge ships, the organizers forced more than 2,000 prisoners – who were thematically dressed as Roman enemies and then ordered to fight among themselves to death. Some of these grandiosely conceived naumachia events received so much fanfare that later emperors occasionally had to empty the prisons to make up for the massive number of ‘fighters’ aboard the ships.

According to one particular incident (as mentioned by Suetonius), when the inmates aboard the ships made their customary proclamation of ‘we who are about to die, salute you’, emperor Claudius made a grave mistake of responding ‘or perhaps not!’. This instilled a new sense of hope among the prisoners, who steered away from their vessels from each other. Such ‘peaceful’ moves instigated the spectacle-hungry audience members to start rioting.

Thereupon, Claudius became furious and had to threaten to massacre these rowdy viewers by sending in his troops. Fortunately, the survivors of the mock naval battle were allowed to live. Consequently, the later naumachiae were conducted under the strict supervision of Roman troops who protected the periphery of the lake, while being supported by siege weapons like ballistae and other catapults.

And once again, the popularity of such events is epitomized by astronomical numbers – like one occasion of 500,000 reported people attending a naumachia on the Fucine Lake that was 60 miles east of Rome.

The Chances of Survival of a Gladiator

All of these grave incidences, bizarre laws, and grand spectacles naturally bring us to the question – how much chance did the average gladiator have to actually survive the process? Now, according to the munera traditions, the best fights tended to result in casualties. In the Republic phase, the trends of bloody encounters were actually quite frequent, with some fights already announced to be sine missus (where the loser would die).

However, by the first phase of the Roman Empire, such fights were banned (on the orders of Augustus Caesar) – thus allowing for a ‘nobler’ practice where the defeated gladiator was often pardoned if he showed his courage during the fighting. These changes in societal values mirrored the casualty numbers found in pieces of evidence.

For example, according to historian George Ville, in a hundred analyzed duels from the 1st century AD, only around 19 gladiators died out of the studied 200 specimens. But such figures took a worse turn in the succeeding years of the Roman Imperium wrought by internal conflicts and harsher measures. In that regard, by the 3rd century AD, it is estimated that at least one of the gladiators got killed or succumbed to his injuries in every alternate combat scenario.

Rudis – the Symbolic Wooden Sword of ‘Freedom’

With all said and done, there was still hope for the actual gladiators (as opposed to the criminals) to gain their freedom from exploitative bondage. Such measures of pseudo-freedom were offered to gladiators who had demonstrated exceptional courage and fighting prowess during their long gladiatorial tenures. This was symbolized by the rudis – a wooden sword that was presented to the participant on such very rare occasions.

Now, we used the term ‘pseudo-freedom’ because, by the very nature of segregated Roman laws, gladiators couldn’t truly be designated as free men. However, the fame and fortune that could be gained by their dashing feats inside the arena still inspired many gladiators to fight for the rudis – thus seemingly alluding to the fundamental nature of man and his simple freedom.

*Note – The article was updated on January 3rd, 2020.

Sources: University of Chicago / History Today / VRoma / BBC / AbleMedia

Book References: Gladiators 100 BC-AD 200 (By Stephen Wisdom) / Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome (By Eckart Köhne, Cornelia Ewigleben)

Be the first to comment on "Roman Gladiators: The Bloody Origins and History"