The controversial rise, the enviable peak, and finally the ignominious fall – this, in a nutshell, defines the historical spectrum of the elite Janissaries of the Ottoman Empire. However, beyond contentious (and often biased) perspectives, there is no doubt that the famed Janissary Corps of the Ottoman Empire played its pivotal role on many a battlefield ranging from Europe to Asia (from circa 15th to 17th century).

Their unique training and discipline bridged the tactical gap between the missile and assault troops. So without further ado, let us take a gander at the origins, military, and culture of the Janissaries – often heralded as the precursor to Eurasia’s first modern army.

Contents

Origins of the Janissaries

Beyond ‘Slave Soldiers’

Like the traditionally unfair historical treatment of the Eastern Roman Empire (which is conventionally called the ‘Byzantine’ Empire), the Ottoman Empire (or Turkish Empire) also meets its fair share of prejudice in historical circles, especially regarding the discussion of the famed Janissaries. To that end, while often dismissed as mere ‘slaves’, there was obviously more to the Janissaries when it came to their social scope.

For example, it is highly probable that the first Janissary units were recruited from the Christian prisoners of war who were converted to Islam. This alludes to their fate (of being elite soldiers) which is far more agreeable than the brutal capital punishments reserved for foes during the earlier Crusades.

However, this initial system was replaced by the state-sanctioned levy of Christian subjects by the Ottoman ruling class. As historian Dr. David Nicolle noted, the classification of a slave in medieval Islamic society is rather misleading, if perceived through the lens of our modern sensibility.

In that regard, in Ottoman society, a slave or a Kul often enjoyed more social benefits and even better opportunities than an ordinary subject (as opposed to oppression), at least till the 17th century. Essentially, they displayed their ‘slave’ status with pride, thus mirroring their predecessors and contemporaries, like the Ghulam and the Mamluk – the latter of which even formed their ruling dynasties in Egypt.

Dervishes And Christianity

The origins of the Janissaries rather reflected the dynamic nature of the nascent Ottoman state in the 14th century. It was a realm originally founded by refugees from the Mongol invasion. Within decades it was transformed into a burgeoning principality (beylik) that started to incorporate a unique form of syncretism – where some elements of traditional Islam were mixed with both pagan Turkish shamanism and Christianity followed by many peasants.

The dervishes (Muslim ascetics) who were often considered heretics in other Islamic domains, took center stage in Ottoman military affairs with their disparate followers (Muslims and Christians alike) and brotherhoods populating the rural regions bordering the Byzantine Empire.

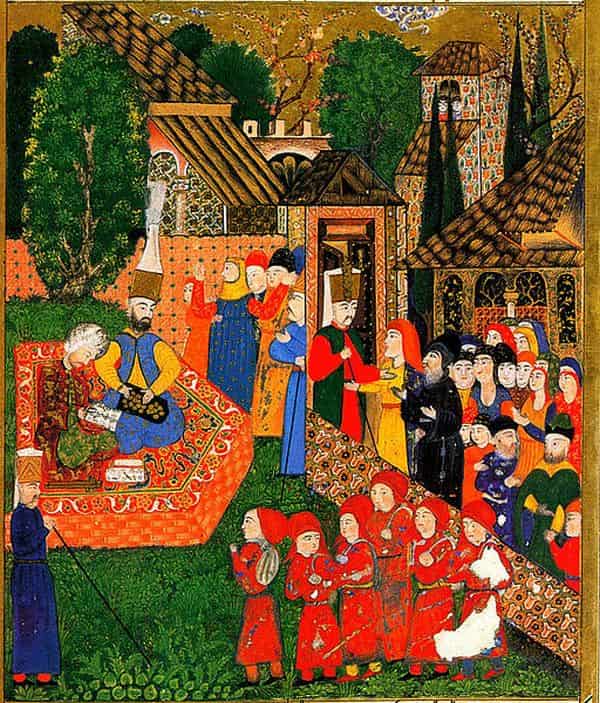

Among these dervishes, it was the Bektashi sect that possibly played an influential role in the creation of the first Janissaries. According to one traditional account, it was Ali Pasha (who might have been a Bektashi himself) who convinced Orhan, the second chieftain (bey) of the Ottoman Sultanate to create his ‘new soldiers’ – yeñiçeri (meaning ‘new soldiers’).

These men were attired in white caps to distinguish themselves from the rest of the army. Coming to their recruitment, as we mentioned before, many of the initial Janissary troops were simply captured Christian soldiers who were given the option of converting to Islam and serving the Ottoman state.

This relatively open-minded scope allowed for Bektashi dervishes to serve as dedicated chaplains inside Janissary barracks, and these ascetics, in turn, were influenced by the initial Christian beliefs of the recruits.

In fact, the teachings of Haji Bektash Veli (the founder of the Bektashi dervish order) were sometimes identified with that of Orthodox Christian saints. Such synergistic religious overtones translated to unexpected displays, like the carrying of gospel quotations by many Janissary troops as lucky charms.

However, from a logistical perspective, the number of POWs was not enough to fill the ranks of the Janissaries. Thus over time, the state formulated the sourcing of slaves (kuls) who could be trained as soldiers, mainly from the newly conquered region of Thrace.

Essentially, these new soldiers replicated the style of the effective Eastern Roman Empire and Serbian infantry archers (Mourtatoi), and thus it might not be a coincidence that the early Janissaries served as heavy archers. On the practical level, the Janissary archer bodyguard units gradually replaced the irregular Yaya infantrymen – the previous mainstay of the Ottoman military used for siege scenarios.

The Infamous Devsirme

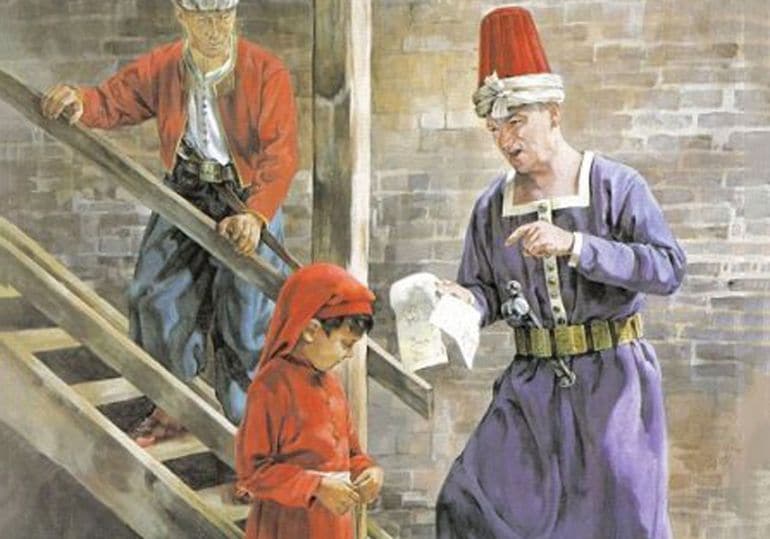

But as the Ottoman beylik grew into the Ottoman Empire, the ‘makeshift’ system of acquiring full-fledged slaves for Janissaries was deemed to be inadequate. Thus the controversial Devshirme (or devşirme – literally meaning ‘lifting’) system was adopted. This was a sort of blood tax that enabled the recruitment of one Christian child or youth from every 40 households, with their ages varying anywhere between 8 and 20.

This form of recruitment was possibly initiated in the 14th century and probably happened once every five years, especially in the Christian territories conquered in the Balkans (which still had their Christian majority). According to scholarly estimates, a fully initiated Devshirme could account for over 1,000 youths (to 3,000 youths) in a single year and cover just a part of the quota of 8,000 male kuls required by the state.

The recruitment drive for Janissaries was mainly focused on the rural areas of the Christian Balkans (and later Anatolia), whereas large cities, islands, and strategic passes were largely exempt from the Devshirme.

The idea behind this was that the recruiters looked forth to healthy, ‘rough’ boys (as opposed to streetwise and ‘soft’ urbanites) who could be molded and easily indoctrinated into the religiopolitical and military scope of the steadily ascendant Ottoman Empire. Interestingly enough, the very same philosophy was also applied 1,400 years ago by the Romans when it came to conscripting their legionaries.

However, judging by the seemingly flagrant structure and agency of this system, suffice it to say, Devshirme was initially not popular among the Ottoman state’s Christian subjects – with several instances of local resistance against the policy. Even the Muslim scholars and Ottoman Ulama of the contemporary period didn’t look kindly upon the forcible recruitment of youths, which was perceived as a violation of the rights of the Christian subjects.

But over the course of a century, with the rising social status and military prestige of the recruited Janissaries (rather bolstered by their well-to-do economic means), there were some families, especially the impoverished ones, who preferred their children to be ‘lifted’ by the authorities.

By the 15th century, a few Christian (and sometimes even Muslim) families bribed the officials to take in their children, while the Bosnian converts were the only Muslims formally allowed for recruitment through the Devshirme.

However, by the late 16th century (circa 1594 AD), given the chronic shortage of manpower for the elite Janissary corps and the existing political climate, all Muslim males (of the Ottoman Empire) were finally allowed to be recruited. This period coincided with the tumultuous reign of Sultan Murad III.

And ultimately, by the mid-17th century, Sultan Mehmet IV abolished the ‘redundant’ Devshirme as a recruitment system. The decision was made because a significant number of originally Muslim Turkish families already had their scions serving in the Janissary ranks of the Ottoman army.

The Systematic Organization of the Janissaries

The Education

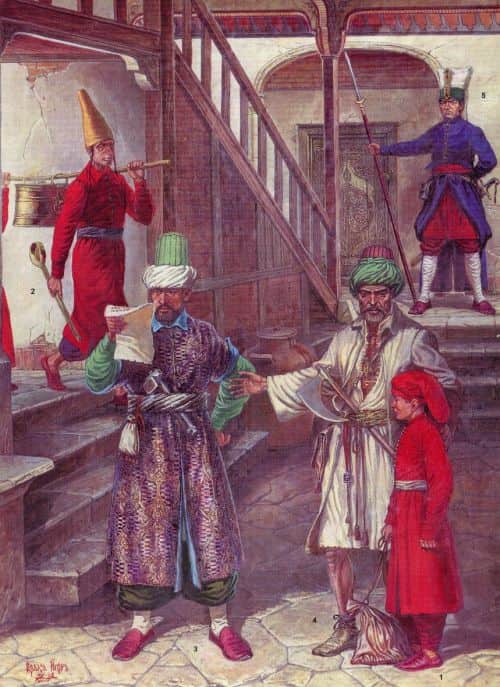

Now it should be noted that with the evolving nature of the Devshirme system, not all the youth recruits were trained as Ottoman Janissaries. A few of them, noted for their apparent intelligence, were selected as iç oğlan (or inner ‘service’ boys) – and they were sent to the palace schools (after several tests that involved aptitude and IQ tests).

Consequently, they were offered the best of education the state had to offer in numerous fields like administration, religion, military, and court etiquette. They were additionally trained in literature, horse riding, archery, wrestling, and even music.

Among them, the brightest were further appraised and selected as loyal staff members of the Sultan’s palace, an initial position from where they were destined for higher offices. The rest of the iç oğlan were drafted into the cavalry arm of the elite Kapikulu (‘door slave’) corps – the household troops of the Ottoman sultan.

As for the other youths ‘lifted’ through the Devshirme system, they were called the acemi oğlan (foreign boys) – and most of them were drafted into the Janissary Corps of the Ottoman Empire. And while their basic education mirrored that of the iç oğlan, the emphasis was more on obedience and military tactics.

Training Period

In fact, the majority of the aforementioned acemi oğlan had to initially serve as Türk Oğlan – basically glorified farmhands who worked in the estates of esteemed Turkish families for a period of seven years. During this time, they were not only accustomed to labor but also had to practice their ‘newfound’ Muslim faith. And after the seven years were completed, the youths were sent to the Acemi Ocak (basically the ‘training camps’) for advanced military drills and weapons handling.

Interestingly enough, a few of the Türk Oğlan candidates, the ones who showed their aptitude in tests, were directly selected for the functioning auxiliary Janissary divisions (or Ortas – each composed of 50-100 men), like Bostanci (‘gardeners’) and Baltaci (‘woodcutters’).

From there they were often promoted to specialized corps, like the gunners and the armorers. A few others were also taken in by the rich households (Konaks) of pashas and beys, to be further educated and trained in the elite provincial side of affairs.

The rest of the youths, as Dr. Nicolle mentioned (in his book The Janissaries), were inducted into the Acemi Ocak – and their military training was imparted over a period of six years, after which they were eligible for employment via the regular operational Ortas of the Janissaries.

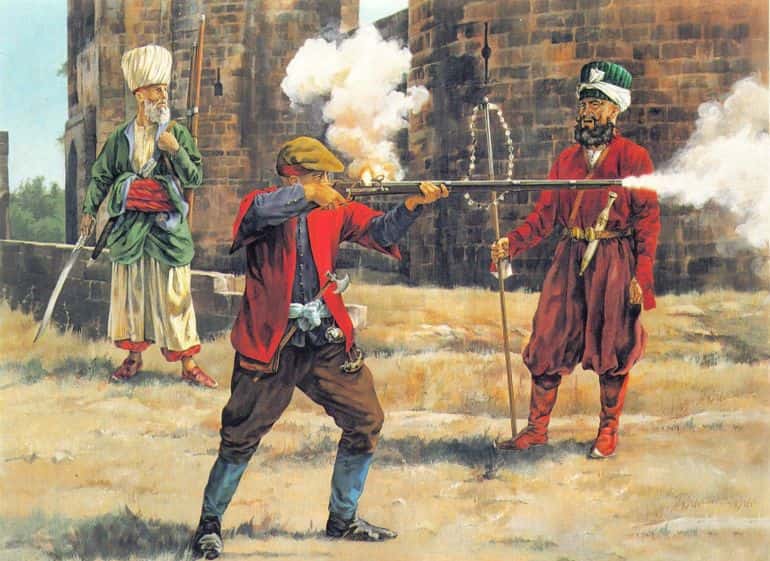

During this time, the young Janissaries trained in the use of a variety of weapons, including bows, muskets, javelins, and even swords (for fencing). The bevy of instructions, deep guidance, and incessant practicing courses provided by the military officers and professors were quite effective – if we go by the contemporary records documented by their European foes like the French and the Austrians.

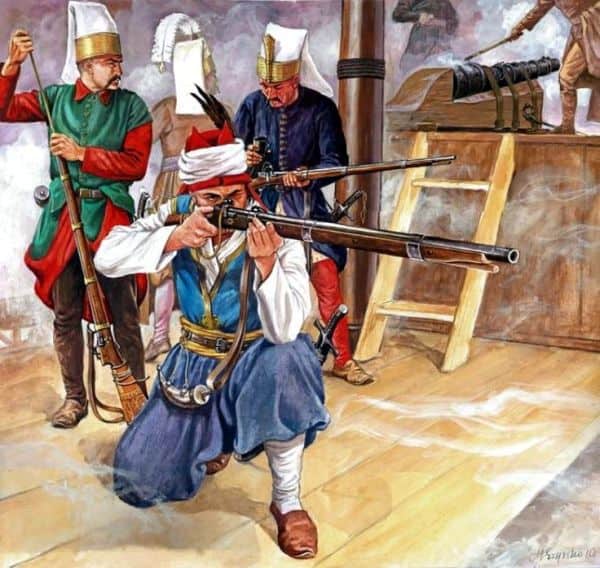

According to some of these sources, the Janissaries were extraordinary marksmen who could not only aim accurately but also maintain a fast rate of firing, even under moonlights. Suffice it to say, such high skill levels were rather reinforced by strict discipline, which led to youths being supervised by specially appointed eunuchs who didn’t allow female company within the training grounds.

The Organizational Structure and Numbers

In many ways, the Ottoman military mirrored the legacy of their Eastern Roman (Byzantine) foes, with the provincial army (Eyalet Askerleri) and the Sultan’s standing army (Kapikulu Askerleri). Pertaining to the latter, they unsurprisingly formed the elite divisions.

And within this Ottoman standing army, the infantry (Kapikulu Piyadesi) were mainly composed of the Janissary Corps (Ocak) and related support and auxiliary units (like armorers, artillery, and even water carriers). Now we already mentioned before how the manpower of these regular Janissary divisions was mainly derived from the trained acemi oğlan, who in turn, were ‘lifted’ (initially) from the Devshirme system.

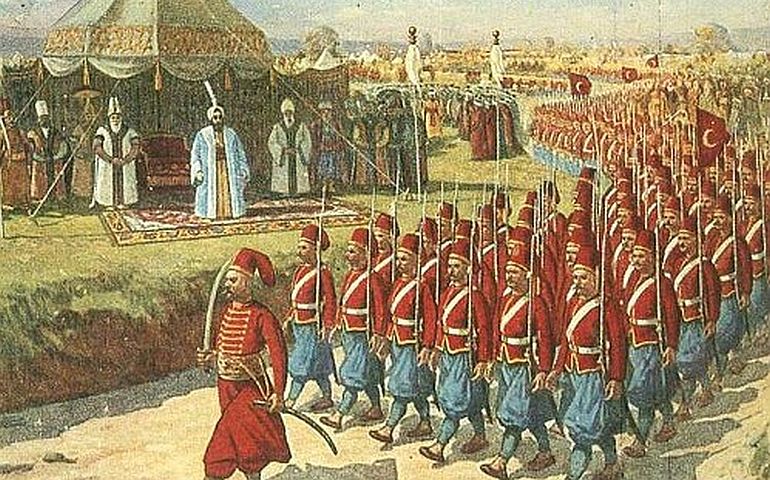

In any case, the actively serving Janissaries, whose numbers initially started from just 8,000 in the late 15th century – which was probably only ten percent of the overall Ottoman army. Their numbers crossed 20,000 by the late 16th century and peaked at 67,000 in circa 1699 AD.

They were mainly divided into three groups – the largest Cemaat (or ‘assembly’) – which served as frontier troops and comprised 101 ortas (divisions), the Bölük (or ‘division’) – who served as Sultan’s personal bodyguard and comprised 61 or 62 ortas, and finally the Seymen – who served as smaller guard units (34 ortas, each with 70 men) armed with matchlock guns and swords.

Judging by the numbers and their respective roles, it can be determined that the Cemaat played a crucial role in the numerous military encounters across the battlefields of Europe and Asia. Among them, the Solak Ortas formed the elite guard divisions and curiously enough also included the unique müteferrika – heavy cavalrymen recruited from the sons of many Balkan and Turkish noblemen who were basically political hostages in the service of the Sultan.

Considering the sheer scope and complexity of logistics involved in these formations and military structures, the Janissary Ortas were distinguished and represented by various insignias, flags, and other visual clues that alluded to their origins, names, and even special commanding officers.

And talking of commanding officers, the overall commander of the regular Janissaries was offered the rank of Yeniçeri Ağası – and the general was directly chosen by the Sultan (and whose role later extended to the ‘chief of police’ in Istanbul).

And such was the power of this rank that his orders couldn’t even be questioned by the Grand Vizier. Simply put, only the Sultan was considered the supreme commander of the Janissaries. However, in practical circumstances, the collective decisions regarding the corps were made by the members of the Divan (Council) which also comprised the commanders of other related units like the Bostanci.

Culinary Symbolism and the Kazan Pot

The famed Janissary Bayrak (or banner) pertained to the white silk flag with its specific inscription dedicating their victories to Prophet Mohammed. On the other hand, legends talked about how Orhan presented a red flag with a crescent to the first batch of the Janissaries, while the white star was added after the conquest of Constantinople – thus giving form to the modern flag of Turkey.

At the same time, many of the earlier Janissaries carried Greek gospel quotations as lucky charms, which rather harks back to their originally Christian and syncretic beliefs.

However, beyond religious motifs, the Janissaries had a rather unique penchant for culinary symbolism. The main element of this scope was the Kazan, a huge copper pot of each orta where the daily communal meal of pilav (made of bulgur wheat and butter) was cooked. In essence, the pot alluded to the fraternity and brotherhood of the Janissary battalion members, and such was perceived as the most treasured possession of the division.

As such, it was carried during parades in solemn silence and even used as rallying points during battles. On the other hand, losing the Kazan in battles often resulted in disgrace for the entire unit (and they were barred from parading with other divisions), while upturning the Kazan marked the mutiny of the division. And since we are talking about culinary symbolism, some Janissaries were also known to wear their dervish-inspired hats with wooden spoons attached at the front.

The Arms, Armor, and Military Effectiveness of the Janissaries

Armor and Uniforms

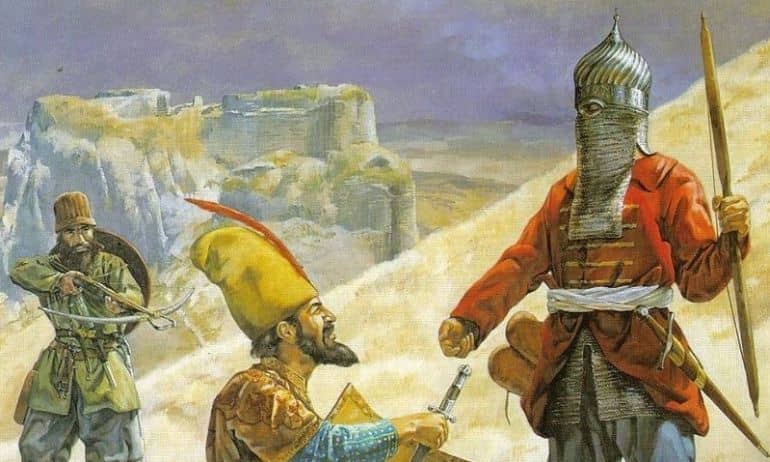

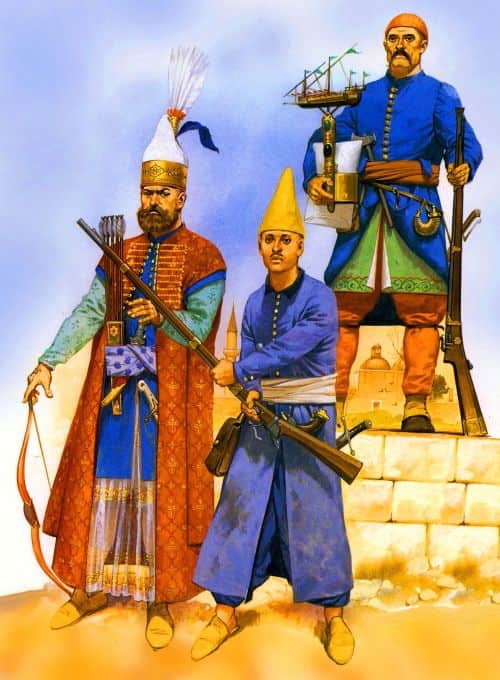

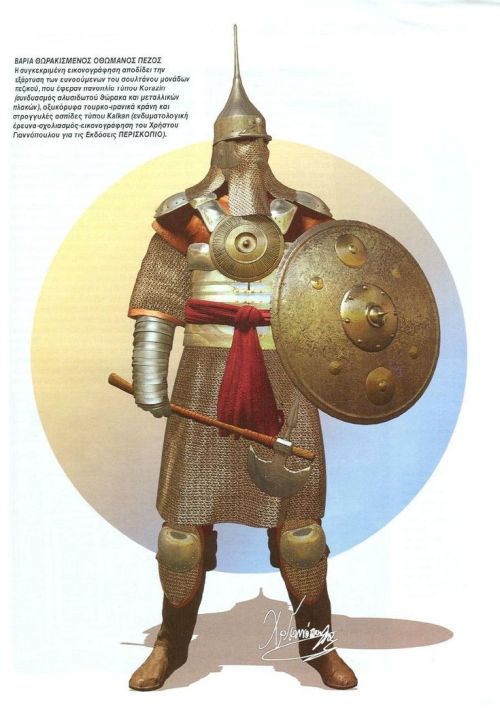

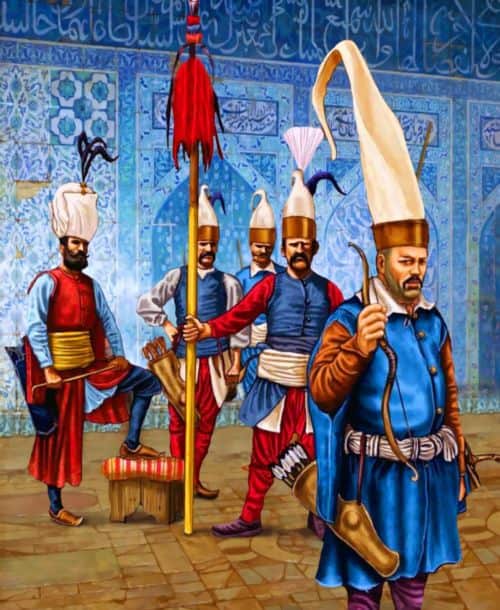

Though not much is known about the armor adopted by the early Ottoman Janissaries of the 14th century, it can be assumed that given their primary role as heavy infantry archers, many of them wore mail hauberks beneath their colorful Dolama coats, while also flaunting their bulbous-shaped Turkish turban helmets. Some of their melee-oriented assault brethren (Zirhli Nefer) possibly continued to wear special mail-and-plate cuirasses and gilded helmets with plumes till the 16th century.

By the late 16th century, like many contemporary Islamic realms, the various attires of the Janissaries were inspired by Persian fashion, and as such their intricate dressing codes often mirrored the formal military occasions. As for the common uniforms, they were made of wool and mostly manufactured in and around the workshops of Thessaloniki.

The cloth was usually covered by a lightweight (and possibly waterproof) felt robe or coat called the capinat (or kapinice) and knee-high boots. But the most distinguishing feature of the traditional Janissary uniform arguably pertained to the dervish-inspired headgear and hats – the style and arrangement of some rather denoting the rank of the Janissary. Higher-ranked officers also tended to have their coats lined with fur sourced from a bevy of critters, ranging from foxes, and lynxes to squirrels.

The Early Weapons and the ‘Headriskers’

Now like we mentioned in the earlier entry, the first of the Janissaries probably served as heavy infantry archers – often called the Nefer Janissaries. To that end, according to Dr. Nicolle, quite intriguingly, some of these specialized bow-armed troops used a type of arrow guide known as siper for precise aiming of deadly darts and projectiles.

The primary composite bow was accompanied by secondary weapons like short spears and swords. The latter, mostly adopted by the 16th century, included a variety of blades like the famed Turkish kılıç, the double-curved yatağan, and the broad gaddara.

Interestingly enough, beyond just archery divisions, some of the 14th-16th century Janissaries also performed their roles as heavy assault troops. These Zirhli Nefer (‘armored soldiers’) were probably part of the elite regiments of Serdengeçti (‘head-riskers’), and as such took the leading role in breaching enemy defenses and close-quarter battles.

In combination with their heavy armor (in the form of mail-and-plate cuirasses) and gilded helmets, these soldiers were also armed with an array of deadly weapons, ranging from maces, teber axes, to polearms like tirpan (glaive) and harba (guisarme) and balta (halberd).

The Adoption of Guns

By mid 15th century, the bow was soon relegated to a ceremonial weapon, with Janissary ortas opting for firearms – namely the matchlock arquebus, possibly after perceiving their effectiveness during the Hungarian campaigns (though some sources mention how few of the Janissaries were already familiar with firearms in late 14th century).

Thus the trademark weapon associated with the Ottoman Janissaries at their military peak pertained to the heavier version of the arquebus with longer matchlocks and larger bore (when compared to European firearms). The largest of these devastating tüfek guns could fire bullets of 80 gm weight.

However, by the 17th century, most of the Janissary corps adopted the flintlock varieties that were already pretty common in the European armies. Known as miquelet, these guns were easier to clean though at times unreliable in the hotter Middle Eastern theaters of war. In the latter half of the 17th century, some of the Janissaries also began to use pistols, possibly inspired by their Venetian foes.

However, oddly enough, the regular Janissary continued to abhor the bayonet – the typical melee weapon associated with guns, well into the 18th century. The reason probably had to do with what they perceived as the ‘herd mentality’ tactic of charging into enemy lines. In contrast, the Janissary tended to value his individualistic warrior ethos.

The Offensive Tactic

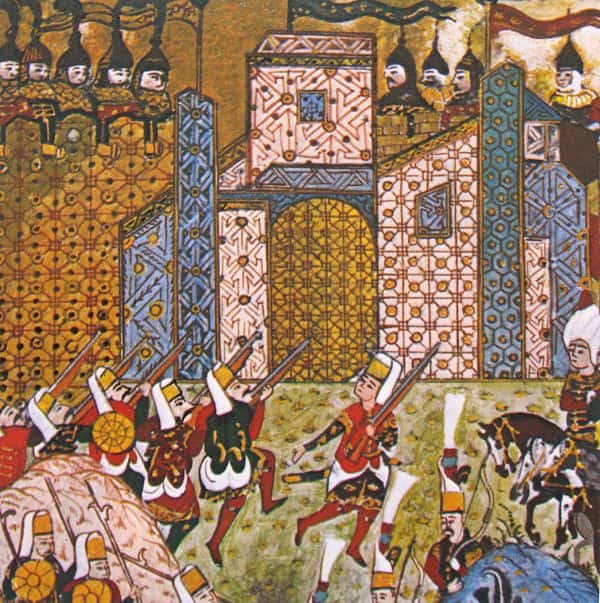

The 16th century arguably demonstrated the apex of military domination by the Ottoman Empire with the incorporation of combined arms that conferred the tactical use of cavalry, infantry, and artillery. As aptly described in the Armies of the Ottoman Turks (by David Nicolle), the combined arms mirrored an organized, ‘classic’ battlefield tactic where the main army body entrenched themselves within field fortifications, gun-wagons (taburs), and man-made ditches.

At the center of this massive body stood the sultan with his Solak household guards and the elite Janissary forces armed with arquebuses. This chosen force was flanked on both sides by heavily armored alti boluk horsemen (gathered from the Kapikulu household forces).

In the front and rear of the arrayed artillery stood the azaps, light infantrymen armed with bows, axes, and swords. On the further flanks stood the provincial Sipahi cavalry ready for mass enveloping maneuvers. And lastly, at the front of these entrenchments, the Ottomans unleashed their akinci – battle-hardened, light irregular cavalry forces that harassed the enemy with arrows and javelins.

So once the akinci forces were successful in aggravating the enemy (which in some cases entailed feisty European knights and gendarmes), the azaps were ready to absorb the charge of the opponent. And once this initial (and often impetuous) charge was mitigated, the azaps opened up their formations for the Janissaries.

One could only imagine the devastating effect of the firing arquebuses unleashed upon the enemy forces – who were already surrounded by Ottoman ranks. And while the armored foes were ‘shocked-and-awed’ by combined destructive barrages of artillery and the deafening shots from the arquebuses, the flanking Turkish cavalry played the major role in surrounding the remnants of the enemy army and then mopping them up in a piecemeal fashion.

It should also be noted that on occasions, the Janissaries took on upon themselves to charge the enemy lines, though not in unison, but in tactical groups (with wedge formations). These strike teams were often headed by their heavy assault teams of the aforementioned Serdengeçti (‘head-riskers’) and encouraged at the rear by the Janissary music of Mehter military bands.

And talking of tactical measures, the Janissaries uniquely tended to avoid massed volleys, thereby relying on their expert marksmanship and skills to take out the weaker sections of the enemy lines and fortifications.

Moreover, their warrior culture was ingrained in the pursuit of bravery and battlefield glory, with many of the Janissaries competing for badges and medals (and sometimes financial prizes), including the plumed Çelenk that was only awarded for showing courage in the face of an overwhelming number of foes.

The Ottoman Discipline

The success of the battlefield was however not just limited to complex planning maneuvers; the Ottoman Janissaries, in their apical years, also showcased their brand of fierce discipline during marching and camping, which was in stark contrast to many of their European adversaries.

Such measures entailed frugal food habits inculcated among soldiers of all statuses ranging from officers to common infantrymen. This was backed up by proper sanitation measures inside the camp and prohibition of alcohol consumption during marching – which led to practical mitigation of camp diseases and curbing of rowdy army behavior common during the time.

But arguably the most striking feature of an Ottoman camp was the eerie level of quietness demonstrated by the troops – as documented by many European observers. Bertrandon de la Broquière, the 15th-century Burgundian spy, and pilgrim to the Middle East, once observed the Janissaries and commented on how (sourced from The Janissaries by David Nicolle) –

…a hundred armed Christians could make more noise leaving their camp than ten thousand Turks. All they do is beat a large drum. Those who are supposed to leave get in the front and all the rest fall into line, without breaking up the order.

The Martial Culture of the Janissaries

The Code

Given their penchant for discipline (in contrast to some contemporary European troops), it doesn’t come as a surprise that the Ottoman Janissaries were governed by their own military code and ethics. 16 of these major guidelines were formulated by Sultan Murad I himself, the architect of Ottoman ascendancy in the Balkans, in the late 14th century.

Some of these rules entailed – total obedience to the superior officer, maintenance of strict military behavior, promotion based on seniority, and punishments applicable only when given by their own officers.

A few of the tenets also alluded to the social side of affairs, with the Janissary recruits not allowed to keep beards, only allowed to live in barracks, and not allowed to formally marry until retirement (though the rule was relaxed by circa 1566 AD), not allowed to gamble or consume alcoholic drinks, and quite uniquely not allowed to display extremes of either wealth or abstinence.

As for punishments, which could only be doled out by officers of the Janissary Corps, the most common one involving the soles of the accused’s feet being beaten by the falaka canes, after which the punished had to kiss the hand of his punisher – thus symbolizing his return to the fold. Other serious punishments were handed out in the case of the destruction of property, with adequate compensation being offered to the civilians (at least in theory).

As for the death penalty, it was reserved for deserters who were caught in times of war. They were unceremoniously strangled and their corpses were then discreetly dumped in proximate water bodies during the night to allay any sense of public shame.

Lifestyle and Payments

Each of the around 200 ortas of Ottoman Janissaries functioned as a military fraternity whose members were housed in their own barracks – large, well-furnished establishments (known as oda), with living quarters, kitchens, and arsenal.

Some of the elite ortas were stationed within the confines of the Topkapi Palace compound, with the two Janissary oda at Istanbul flaunting their impressive stone structure embellished with colored tiles, marbles, fountains, and gilded doors while being surrounded by supply workshops run by local civilians.

In fact, the ‘local Janissaries’ stationed inside cities across the Ottoman Empire were often called Yerliyya. In spite of their military service and background, some of these Yerliyya also took part in commercial and political activities of the area – with the frequency rather increasing in the later years of the Ottoman Empire.

However, within the ostentatious walls of the barracks, the Janissaries lived a rather monastic lifestyle, secluded from the outside world, but drilled in discipline and obedience (at least till the 16th century). Bertrandon de la Broquière mentioned how these highly disciplined and motivated troops could subsist on frugal food (that included just bread, dried meat and fruits, and porridge made from basic flour) during their daily marches.

At the same time, the orta members saw themselves as a part of the brotherhood who looked after each other – so much so that even after the death of a fellow Janissary in battle, it was the responsibility of the entire orta to provide food rations and work for the closest family members of the deceased.

However, from the legal perspective, it was the regiment that inherited the property of the dead Janissaries. On the other hand, the retired or discharged Janissaries did receive pensions, while their children were often also looked after by the orta.

As for payments, Dr. Nicolle talked about how the regular Janissary was expected to receive his ulûfe (pay) around three to four times a year, with the payday usually coinciding with the visit of foreign dignitaries. He was also offered extra money to purchase his bow and arrows while being given a ‘ration’ of cloth that could be used for making a few attires. This was complemented by bonuses that were offered to special units like the Serdengeçti.

However, in spite of the relatively high status of Janissaries, their initial pay didn’t really reflect their elite position in the Ottoman army. But over time, especially by the latter half of the 15th century, Sultans were more willing to raise the pay grade and bonuses of the Ottoman Janissaries – possibly because of the rising political influence of the corps.

The Decline of the Janissaries

Politics and Entitlement

But history is witness to how time is the ultimate enemy when it comes to the upheaval and corruption of power and influence. Consequently, the downfall of the Janissaries was borne by their own excesses. Mirroring the politically motivated attitude of the ancient Roman Praetorian Guards, the Ottoman Janissaries played a leading role in the various palace coups of the 17th and 18th centuries, by virtue of their increasingly autonomous status within the realm.

In fact, the unbridled scenario faced by the Turkish empire was more complex when compared to their ancient Roman predecessors. This is because the Janissaries had greater numbers and deeper alliances with potent forces within the vast Ottoman territories (as opposed to the influence and machinations of the Praetorian Guards focused on the city of Rome itself).

Even in the late 16th century, with their newfound power in political circles, the Janissaries pressured the Sultan to make their rank partially hereditary. Simply put, the Ottoman state was forced to pass a law that allowed the sons of former Janissaries to enlist in the corps. Thus the new law (which was previously illegal for almost 300 years) permitted Janissary children, who had little or no military training, to be inducted as Janissaries.

After a few decades, in 1622, Osman II, the teenage sultan even tried to curb Janissary excesses. But the Janissaries, under the pretext of a snow-driven famine in Istanbul, audaciously took the Sultan captive and had him strangled inside the Yedikule Fortress (also known as Dungeon of the Seven Towers).

And by mid 18th century, the once-great Ottoman Empire was a mere shadow of itself, while the once-great Janissary Corps resembled a political (and even commercial) force comprising an entitled salaried class of men rather than a disciplined military institution. At times the Janissary class even rivaled the traditional Turkish aristocracy in terms of political power.

Thus this once professional fighting force, while clinging on to its past glories, had mostly let go of its integral warrior ethos. They were also averse to prescribed changes (pertaining to their training, equipment, and tactics).

The chaos was fueled further when the Janissaries revolted during different phases of the empire – leading to insurrections, and mutinies. These were instigated by the various Janissary branches stationed around the empire.

The Ignominious Fall

More than a century of such machinations finally took its toll in the 19th century, with Sultan Mahmud II, the 30th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, devising the complete abolition of the conservative Janissary corps. One of his predecessors, the reformist Sultan Selim III was actually killed by the political pressure of the revolting city Janissaries.

Sultan Mahmud II, also known for his far-reaching administrative and economic reforms went on to officially disband the Janissaries in 1826. Expectedly, the Janissaries revolted again. It was promptly crushed by artillery shelling of the Janissary barracks, which may have resulted in over 4,000 casualties and exposed the severely lacking fighting capacity of the once-renowned corps.

This was followed by state-sponsored punitive actions against the rebels and their allied Bektashi orders, resulting in swift arrests, exiles (mostly for the younger Janissaries), and executions (reserved for the older leaders of the revolts) – thus unceremoniously heralding the end of the Ottoman Janissaries. Unsurprisingly, it also led to the formation of Asakir-i Mansure-i Muhammediye (meaning ‘Victorious Soldiers of Muhammad’), a modern army incorporated with elements of the defunct Janissary Corps.

Book References: The Janissaries (By David Nicolle) / The Janissaries (By Godfrey Goodwin)

Online Sources: TheOttomans.org (link here) / WarHistoryOnline / I-Cias

Featured Image Source: American Heroes Channel

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork, or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "Janissaries: The Remarkable Origins and Military System Of The Elite Soldiers"