Contents

Introduction – The Islamic Invasion of the Iberian Peninsula

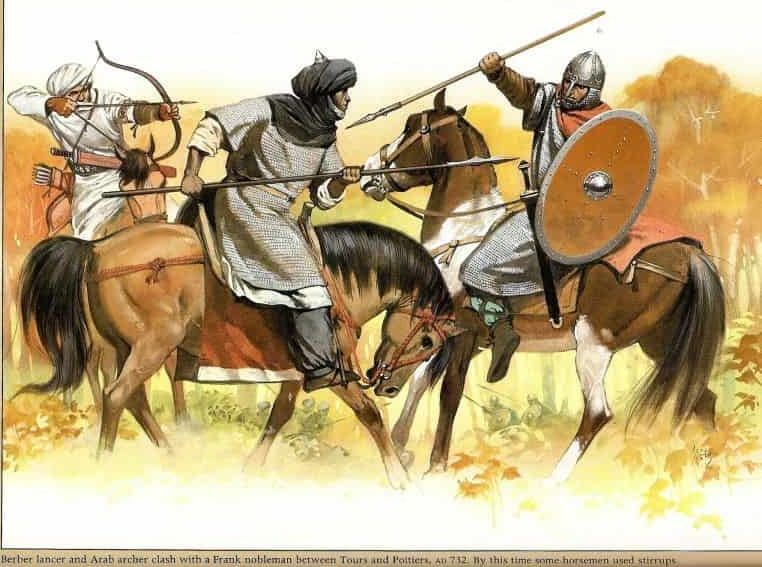

The 7th-8th-century Muslim forces of the Middle East espoused both mobility and tactical prowess, with their manpower mainly drawn from the already urbanized tribes of the Syrian heartland. However, as the Umayyad Caliphate expanded, the forces of the frontier regions were composed mostly of the mawalis (clients).

These mawalis were basically voluntarily-converted adherents of Islam from a non-Arab background, like the Persians in the Khorasan region and the Berbers in North Africa (Maghreb). And it was the latter who played an instrumental role in the conquest of the Iberian peninsula (in the early 8th century AD) – most of which was under the control of the Christian Visigothic Kingdom.

In the century before the conquest of Iberia (Spain and Portugal), the Berbers from Northern Africa were disparate people dominated by authoritative tribes with varying religious affiliations, ranging from indigenous pagan beliefs to even Judaism. By the 7th century AD, the Eastern Roman grasp on this region had already dissipated, and the power vacuum was filled by the Arabs approaching from the direction of Egypt (who were rather aided by the small yet Romanized urban population).

And it was the Islamic tenets of the Arabs that ultimately united most of the Berbers under one banner, with the major conversions starting with the powerful Masmuda tribe. Subsequently, the processes of political consolidation and religious conversions were actively pursued by the Arab governors of Maghreb, thereby resulting in an expeditionary military force bolstered by the newly recruited Berbers.

Furthermore, while land armies were furnished by the newly-converted nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes of North Africa, the Arabs also pushed for naval dominance in the coastal areas. Interestingly enough, according to historian David Nicolle, the fleet was largely built by local Latinized Roman-Africans (afariqa) and Egyptian Copts at the naval center of Ifriqiya (corresponding to modern Tunisia).

And thus the Umayyad forces, composed of converted Berbers, pagan nomads, smaller units of the frontier Arab garrisons, and even some Jewish Berbers, springboarded from Northwest Africa and invaded Iberia in circa 711 AD.

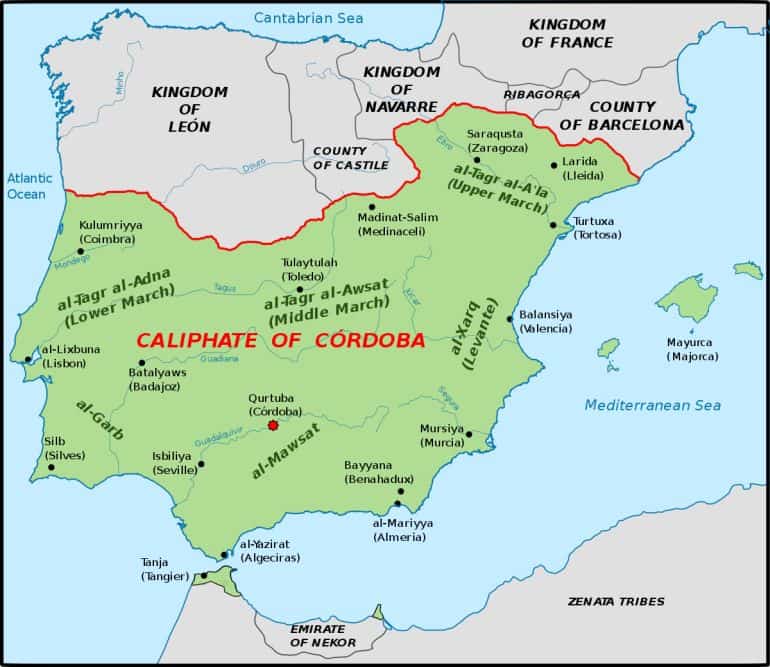

The consequent seven-year-old campaign led to the annexation of most sectors of the Visigothic Kingdom, thereby bringing Muslims to the very edge of what is now southwestern France. This newly conquered region, under Islamic rule (or Muslim control), was given the name al-Andalus and ruled as the frontier province of the Umayyad Caliphate.

The Cultural History of the Moors

Who Were the Moors and Andalusians?

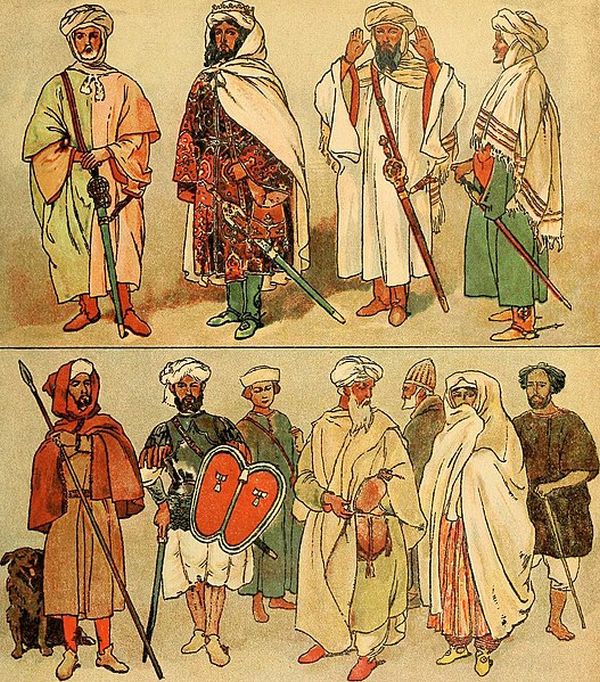

The very term ‘Moor’ is derived from Mauri, the Latin term for tribes of ancient Mauretania (stretching from eastern Algeria to the Atlantic coast). In the medieval context, it was applied more-or-less (sometimes in a xenophobic manner) to all the Islamic adherents and even the Jewish people and local Christians of al-Andalus, along with the inhabitants of Maghreb and distant Sicily.

As for Iberia itself, the society of al-Andalus, under Muslim rule, was mainly divided into three religions – Islam, Christianity, and Judaism; but the people considered themselves Andalusians. This brings forth the question – who were these Andalusians? Well, once again reverting to the communal parameter, like many contemporary medieval societies, the Moors had a hierarchy.

The top of this social pyramid was occupied by the Arab elite, who in spite of being numerically scarce, married into various influential families of the region, including Visigoths, Iberians, and Berbers. These Arabs were followed by the newly-converted Berbers themselves – and both of these groups tended to have a frictional relationship throughout the existence of the Moorish states in Iberia.

However, the most numerically superior of the Andalusians probably pertained to the third group – the Muladis, comprising local Iberians who converted to the Muslim faith after the arrival of the North Africans, along with Muslim people of mixed ancestry (mostly from Iberians and Berbers or from foreign Muslims and local Christians).

They possibly had a middling status in the Moorish society during the beginning phase of the Moorish realm of al-Andalus, with some even designated as slaves. But over time, their status grew in proportion to their important contributions to the judiciary, trade, and administrative systems, thereby resulting in various influential (provincial) Muladi families with native Iberian origins.

The fourth group among the Andalusians (or Moors) comprised the Mozarabs, basically composed of the local Iberian Christians who lived under their Muslim overlords. They were followed by the Andalusian Jews from various backgrounds, including both North African and mixed ancestry.

And finally, the last group pertained to the slaves, with one particular category referred to as the Saqaliba (Slavs). Many of the Saqaliba (mostly acquired through trade routes from Eastern Europe and Eurasia) like Mamluks of contemporary Muslim domains, took up the role of elite guardsmen to governors and sultans, while others were trained or forced to act as harem-eunuchs and servants of the courts.

Cordoba and the Umayyad Legacy

While al-Andalus was geographically the frontier of the Umayyad Caliphate, it also proved to be the refuge of the later Umayyads, many of whom had to flee all the way from Syria to Spain – as a consequence of their Caliphate being taken over by the Abbasids in circa 750 AD. In a particularly chilling episode, known as the ‘Banquet of Blood’, almost all of the Umayyad princes were murdered in cold blood after being deceived by an invitation to a feast.

But one of them, known as Abd al-Rahman I, managed to escape to Iberia, defeat the local Muslim lords, and proclaim himself as the undisputed emir of Cordoba (Qurtuba) – a major city of al-Andalus, by circa 756 AD. This, in turn, resulted in the flowering of a fascinating ‘syncretic’ Moorish civilization in the Iberian peninsula, centered around the city of Cordoba, from circa 8th to 11th century AD.

Keenly guided by the opulent Umayyad legacy, the Emirate of Cordoba blossomed into what can be termed as a regional superpower (later declared as the Caliphate of Cordoba circa 929 AD), especially from the cultural and economic perspective. The city itself possibly supported a population of over 400,000 by the 10th century, which made it the largest urban conglomeration of Western Europe during the Middle Ages.

The sheer numbers of people and patrons were complemented by scores of industries based on textiles, glassware, ceramics, and metalwork. The city and its surrounding lands were also utilized for sophisticated irrigation methods with waterwheels and the introduction of new crops like eggplant and watermelon.

Other densely populated cities, like Seville, also developed during the time period, mostly along the broad Guadalquivir valley in southern Spain – which became the heartland of al-Andalus. And as such huge urban areas cropped up in medieval Spain, their immediate environs were converted into irrigational suburbs and gardens that supported the burgeoning population of the Iberian Moors.

The High Culture of the Moors

Qiyan songs are inspired by the music of Al-Andalus presented in the video above. In terms of history, Qiyan referred to a particular class of non-free yet educated females (in the medieval Muslim world) who were trained in singing, poetry, recitation, and sometimes even shadow puppetry. The songs above were sung by a group called Qiyan Krets. As for history, the third composition (starting at the 7:49 mark) – Lamma Bada Yatathanna is sometimes attributed to Ibn al-Khatib, a 14th-century Andalusian polymath.

Reverting to the cultural aspect, the prosperity of the early medieval Moors was matched by their high culture that contrasted with the rest of contemporary Western Europe and its proverbial ‘Dark Ages’. To that end, Cordoba became a great center of learning, with its royal library, said to have over 500,000 volumes of books and treatises by circa the 9th-10th century (though the number was probably exaggerated by later chroniclers).

Many of these specimens, including philosophical works, were translated Arabic specimens of originally Classical works, along with Indian and other ancient texts. Such feats were rather encouraged during the reign of Al-Hakam II (961-976 AD), the scholarly Caliph of Cordoba.

Beyond learning, the cultural flair of the Moors was mirrored by their adoption of finer customs and commodities in everyday life. For example, Abu l-Hasan, better known as Ziryab, a 9th-century singer and poet who also dabbled in astronomy, cosmetics, and culinary arts, was known for introducing a wide range of habits and inventions to the Moors of al-Andalus, including three-course meals, table etiquette, new food items like asparagus, a precursor to deodorants, and an early form of a pleasant-tasting toothpaste.

The 9th century also saw a revival of artistic works and progression in science and technology across various Islamic realms stretching from Muslim Spain to Persia. The Moors of al-Andalus were no strangers to this trend, especially with their ‘experimental attitude’ (as mentioned by historian David Nicolle) towards both scientific and technological pursuits.

This translated into advancements made in the field of metallurgy, ship-building, and even siege engines. On a related ‘adventurous’ note, a 9th-century Andalusian polymath (of Berber origin) Abbas ibn Firnas even tried his hand at human flight with the aid of flying equipment but failed after a momentary glide and rough landing. Fortunately enough, the inventor escaped with only minor injuries.

And finally, as a form of a unique cultural synthesis, while Arabic (or rather Andalusi Arabic) was the official language of the administration, the Moors of al-Andalus, including top officials and military commanders possibly preferred their Aljami or Latinia – a language evolved from Latin, in domestic circumstances.

The Architecture of Moorish Spain

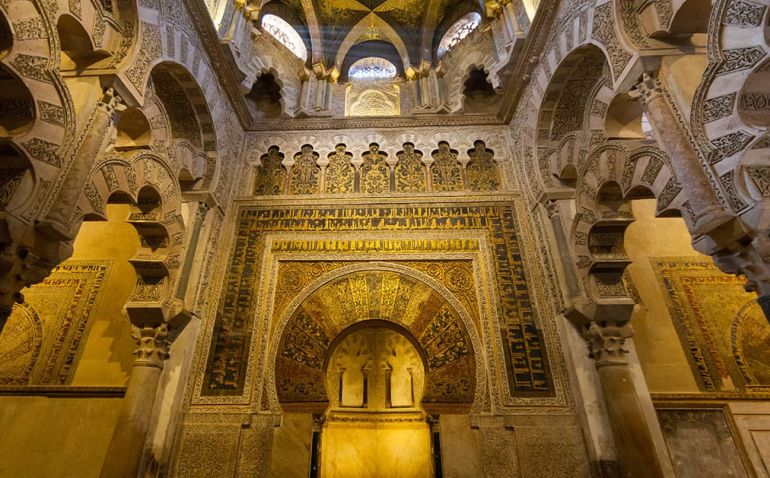

Andalusian cities like Cordoba, Seville, and later Granada were at the forefront of architectural projects that carried forth the styles of their Umayyad forebears along with the incorporation of foreign elements. One pertinent example of Moorish architecture would relate to the Great Mosque of Cordoba (Mezquita) which was erected on the site of a smaller Visigothic church.

The massive structure, while evoking the Umayyad ‘sanctuary’ style, like the Great Mosque of Damascus, also integrated the earlier Roman-style columns. On the other hand, the renowned Alhambra in Granada, constructed as a palace and fortress complex (mostly in the 14th century), does incorporate the facade styles of contemporary Christian strongholds.

Talking of fortifications, the Moors of al-Andalus developed their distinct approach to military architecture by the 9th century, which according to historian David Nicolle, entailed the adoption of circuit walls with closed-spaced towers, along with long stretching walls used for protecting and accessing important water sources by the fort.

However, on flatter terrains, the rectangular plans were modified for more coverage with wider-spaced towers. One grand example would pertain to the Madinat az-Zahra (or Medina Azahara), the magnificent fortress-palace constructed in the 10th century on the outskirts of Cordoba.

As for the sizes and scales, big fortresses of the Moors in al-Andalus known as hisn served as the core military centers, while smaller forts, known as qubba (or burj), and frontier defenses known as rutba, were used for strategic purposes and even as waystations for postal services (barid).

By the next century, smaller castles known as sajra perched atop hilltops and observation towers known as tal’iyya began to appear, thereby alluding to how the conflict was becoming more localized in nature, with a focus on stopping raiders as opposed to armies.

The Military History of the Moors

The Moorish Army

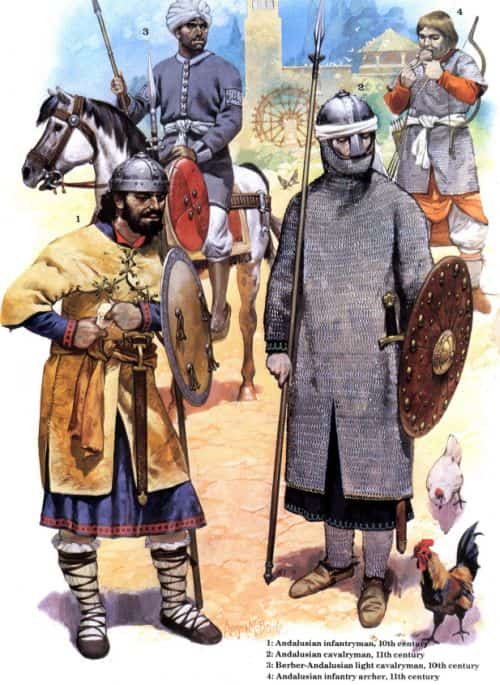

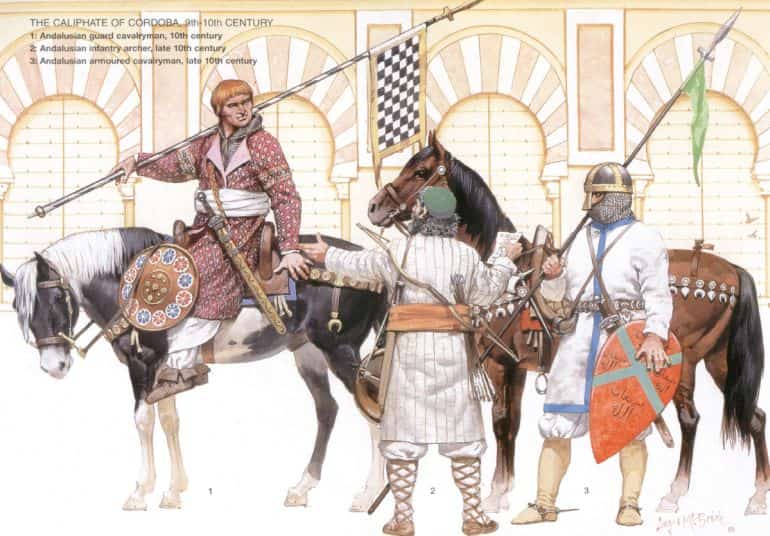

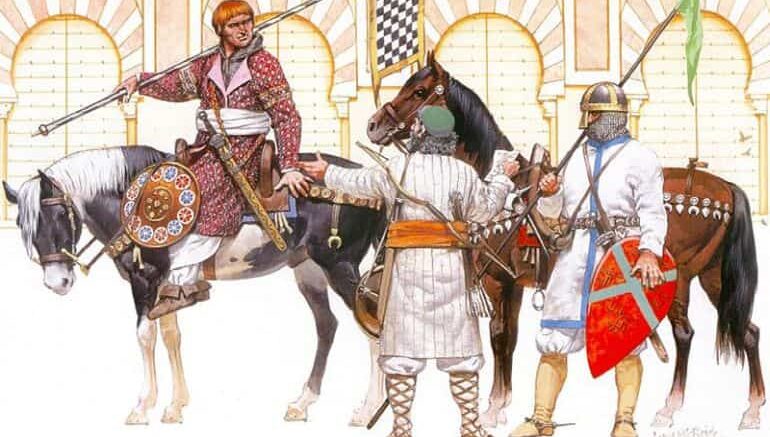

By the mid-8th century, the army of the Moors in al-Andalus reflected its Umayyad origins and influence, with the core of the elite forces derived from the originally Syrian Arab garrisons that played their role in conquering North Africa. However, the majority of the Muslim forces in 8th-9th century Iberia, as we mentioned before, comprised the Berbers.

Over time, as the urban culture grew in demographics, the Berber soldiers were accompanied by the local Andalusian converts, who were known as the daribat al-bu’ut – and these units performed the task of mobile mounted warriors for the still-expansionist campaigns and raids conducted by the Moors on their northern Christian neighbors. The Moors also recruited religious volunteers for the ribat fortifications and coastal defenses, and these units possibly functioned as monastic orders supported by the state.

By the early 9th century, like many other contemporary Islamic cultures, the Moorish caliphs and rulers were guarded by the highly-trained and heavily armored slave soldiers (Mamluks) known as the hasham, with their ranks being filled by recruits from distant lands across Eurasia (procured through extensive trade networks) and even native Christian mercenaries from Iberia.

In the next decades and even centuries, the percentage of slave soldiers and mercenaries rather increased (mainly recruited from the Berbers), especially when al-Andalus was effectively controlled by the hajibs (prime ministers) while rulers only tended to project their ceremonial power.

The Organization and Mobilization

Mirroring the contemporary military organization of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) empire, the Caliphate of Cordoba maintained its three ‘layers’ of forces, with the elite, household, and professional units being based in and around the city itself. The provincial army and volunteer forces formed the second category, while troops and mercenaries specifically recruited for campaigns formed the third.

As for their prestige, it comes as no surprise that the professional forces (known as jund in the 8th-9th century) were given prominence in terms of payment – possibly because many of these units claimed their Syrian heritage (thereby upholding the Umayyad legacy), while the provincial baladis were considered somewhat inferior. The Moors were also known to recruit reserves (nusara) from both the Syrian and baladi regiments, although not much is known about their military structure during the early phases of the Emirate of Cordoba.

As for mobilization or istinfar, the military custom dictated that each province needed to send their allocated number of men, comprising both provincial elites and regular troops, led by arif officers. Two standard-bearers were then appointed for each contingent, with one serving on the battlefront, while the other expected to take up the war duty after three months, in a cyclic fashion. And once all the required men were assembled, harking back to ancient Roman times, they were thoroughly inspected by the royal staff (sahib al’-ard’).

The assembled army was officially reviewed for a period between 20 to 40 days, before the start of a campaign or an engagement. During this time, the ruler and his commanders also formulated the battle plans, alerted the local governors (for safe passage and supplies), and supervised the buruz, a grand parade of the selected troops often starting from Cordoba or from its outskirts at Madinat az-Zahra – the fortress-palace of Moorish Caliphs.

Finally, after deliberations and ceremonies (often entailing bringing out banners from the Great Mosque of Cordoba), the army set out – preferably on the auspicious day of Friday.

Weapons and Armor of the Moors

Al-Andalus, by virtue of its iron-rich deposits and mines (of Roman origins that were revitalized under the Moors), was known for its armor-making workshops, especially rich and gilded varieties that were often exported to North Africa.

The Moors also imported a regular variety of swords and weapons from both Christian Europe and North Africa, while also acquiring high-quality equipment via trade routes from as far as Turkey (especially bows), Eastern Iran, and even India. Composite bows were also made indigenously from materials such as deer and wild goat horns.

Talking of weapons, by the late 10th century AD, the Moors of al-Andalus mainly used three types of swords – the ifranji (Frankish), ‘idwi (Berber style), and the Syrian-Arab style; with higher-ranking officers flaunting their gilded and silvered varieties with bedecked scabbards. And while swords were mainly carried by cavalrymen, they were sometimes also accompanied by tabarzan axes, maces, and possibly even lances.

On the other hand, the ordinary foot soldier tended to carry the rumh or longer qanat variety of spears and pikes, along with javelins and harbah (possibly an early form of polearm). By the mid-11th century, the Moorish armies also made use of the aqqara, a crossbow with a relatively simple design, along with the traditional Arabian bow for mass volleys and the shorter Turkish bows for greater penetrating power (thus sometimes used from horsebacks).

As for armor, according to historian David Nicolle, the dir’ mail hauberk was common among middle to high-ranking soldiers. The elite sultan’s guard (haras) possibly complemented their mail with jawashan lamellar cuirass, the mighfar mail coif (for protecting the face, neck, and shoulders), and baydah ‘egg’ helmets (that were probably replaced by the taller tarikah helmets from circa 11th century).

In contrast, the rank-and-file had to make do with the typical leather or hide armor, sometimes padded with wool. Defensive equipment like shields ranged from the wooden tur to the lightweight leather daraqa.

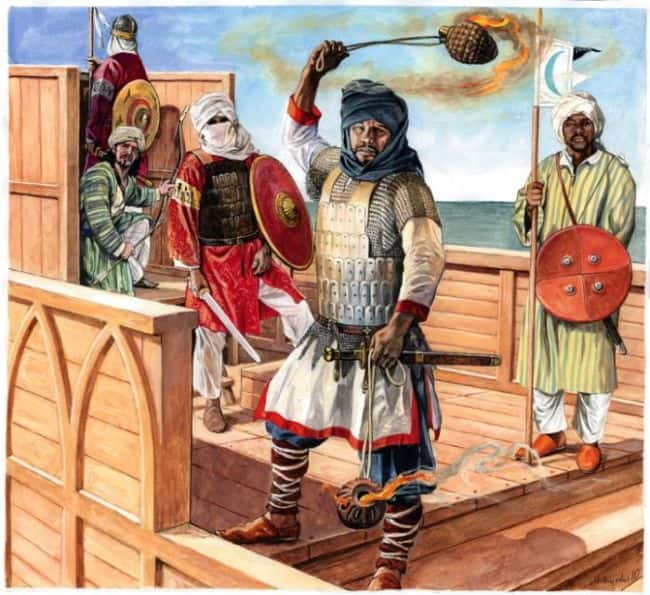

The Naval Power of Moors

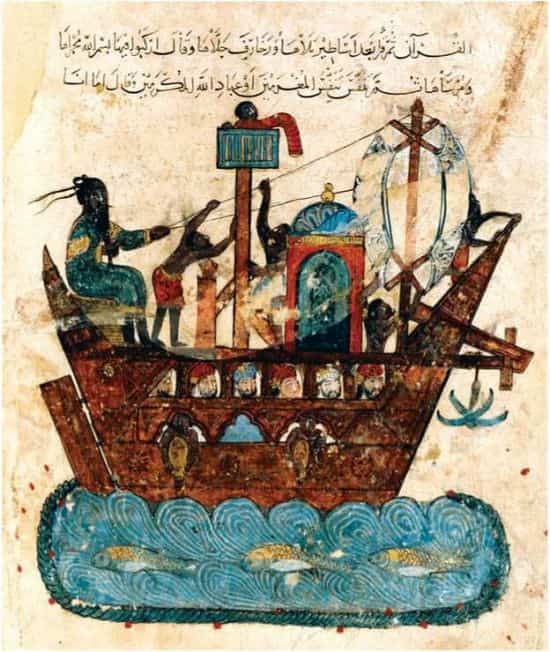

Along with iron, al-Andalus also boasted rich timber sources that were instrumental in maintaining and expanding upon the naval ships of the Moors. As we mentioned before in the article, the naval angle was given consideration even during the Umayyad Muslim invasion of Iberia circa 711 AD, with strategic ports utilized along the coast of Maghreb.

By the 9th-10th century, the Andalusian ships were rather known for their imposing sizes, with one particular cargo specimen captured by their Shia rivals across the Mediterranean – the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt, said to be a whopping 272 ft in length and 108 ft in width.

To that end, many contemporary Islamic militaries of the period did focus on naval pursuits, and it might have been an innate level of competition between the Moors of al-Andalus and the Fatimids that resulted in bulkier ships. Furthermore, North Africa (Maghreb) with its strategic ports tended to play an instrumental role in naval warfare, trade, and development that influenced many a Muslim power along the Mediterranean coasts.

Spurred by the potential arms race and advancements in naval technology, many Islamic kingdoms by the 10th century AD had already begun to take part in mass engagements to directly attack enemy ships as opposed to raiding along the coasts. Interestingly enough, historians have also noted the conspicuous absence of rams in many such warships, which indicated progress in ‘frame first’ shipbuilding technology that allowed the crafts to be sturdier that could mitigate impacts.

As for ship types, Moors probably employed the harraqat ships with fire-spewing mechanisms, the shini galleys that were the mainstay of naval combat – fitted with beaks (instead of rams) for boarding actions, and the larger markab transports used during large-scale military campaigns.

David Nicolle also noted the three-masted ships depicted on 11th-century Andalusian ceramics that were possibly the precursor to the famed qarqura – the later imposing merchant ships of the Islamic empires.

The Political History of the Moors

The Fracture of Al-Andalus Into Taifas

If we glance closely enough at the earlier paragraphs, we can discern that the political power of the Moors in Spain was mostly projected by the Caliphate of Cordoba, one of the most culturally advanced states of early medieval Western Europe.

However, by the early 11th century, the Caliphate was afflicted by what is known as the Fitna of al-Andalus, pertaining to a series of civil wars and in-fighting between the ruler (and his Saqaliba guards and Andalusian bannermen) and his hajib prime minister (mostly supported by the Berbers). The precarious situation was rather exacerbated by the rising power of the northern Christian kingdoms who were increasingly confident and aggressive in both battles and raids conducted across the Ebro valley and beyond.

And while the war-stricken Caliphate barely survived into the 1030s, the proverbial death knell was sounded by the Hammudids, a Berber-influenced Arab dynasty that intermittently invaded the Caliphate from the south and even destroyed the royal palace of Cordoba.

Thus the once-progressive realm disintegrated into many squabbling successor kingdoms, known as the Taifas. Many of these taifas comprised petty parcels of land and thus could barely field hundreds of soldiers, while others, like Granada (then ruled by the Berber-origin Zirids) continued to thrive and recruit more Berber elements, albeit on a far smaller scale when compared to its Cordoba predecessor.

Consequently, by this time, the bulk of the fighting was taken by the Berbers, along with slave recruits of both European and African origins (who often formed the guard units of rulers), while the Andalusians themselves were possibly relegated to a localized state of affairs (especially in Granada and other southern parts of al-Andalus).

As for military equipment, a case can be made for similarities of armor and arms between the Moors of al-Andalus and their 11th-12th-century Christian counterparts of northern Iberia (and even southern France). For example, At-Turtush, one of the most prominent Andalusian political philosophers of the twelfth century, described how a (presumably high-ranking) Moorish soldier was armored so heavily that it covered everything except his eyes, which does evoke the imagery of a fully-equipped Western European knight.

On the other hand, there were differences too, with one 12th-century French source mentioning how the Moors of al-Andalus preferred to wear soft armor over their mail coat and carry a large knife rather than a sword.

The Rise and Fall of the Almoravid Empire

While al-Andalus and its various Taifa states were reeling under the constant Christian pressure from the north (with the idea of Reconquista gaining momentum among the northern Iberian kingdoms), North Africa was undergoing its own religious revolution in the form of the Murabitun movement.

Although, initially starting from the sparsely-populated rural parts of the region, like the Sahara, the movement gained tremendous traction among the various Berber tribes, including the Lamtuna, Zanata, and Masmuda (the first Berber tribe to fully embrace Islam).

Fueled by this progression of affairs, the religious revolution soon transformed into a potent political scope – in the form of the Almoravid dynasty (or al-Murabitun – figuratively meaning ‘those who are ready for battle at fortresses’) centered in Morocco.

The Almoravids, at their peak, commanded troops from the Berber tribes, along with black Africans (many recruited as slave soldiers), Andalusians from across Iberia, and even Christian mercenaries (many inducted into the elite rumis and nasara cavalry units). Incredibly enough, mirroring their Saharan ties, the Almoravids were also known to have conquered distant Ghana and demanded tributes from parts of Sudan by the late 11th century.

As for their involvement in al-Andalus, the momentous episode unfolded at the behest of the Taifa princes. Many of these Muslim rulers were pressured on the northern borders by Alfonso VI (also given the epithet of the Valiant), the Christian King of reunited León and Castile, which led to their decision to ‘invite’ Yusuf ibn Tashfin, the leader of the Almoravids (and also the founder of Marrakesh) in circa 1086 AD.

But what was supposed to be a defense pact, quickly transformed into a full-fledged invasion of Iberia – after ibn Tashfin’s victory over Castille at the Battle of Sagrajas. Consequently, by circa 1094 AD, the Almoravids annexed most of the taifas, often supported by the local Moors who were tired of the constant bickering among their native rulers.

In military terms, the Almoravids were known for making effective use of solid phalanxes of infantrymen protected by their large lamt shields (made of hide, leather, cloth, and iron) and armed with mizraq javelins, with their formations often guarded by elite hasham rear-guards and cavalry formations on the flanks.

Unfortunately for the Murabitun, many of the Almoravid (also called Murabit) rulers in al-Andalus (by circa mid-12th century) were caught between the orthodox, hard life of their Saharan predecessors and the comfort-aspiring, urbane attitudes of Iberian Moors. The supporters of the former lifestyle actively looked down upon the ‘soft’ nature of Andalusians, while North Africa went through yet another religious movement – this time undertaken by the more puritanical Almohads (al-Muwaḥḥidūn).

Ultimately, the combined pressure from Christian advancements in the north (in Iberia) and Almohad resurrection in the south (in Africa) crumpled the Almoravid Empire, with the conquest of the symbolic city of Marrakesh by the Almohads in 1147 AD marking the end of the al-Murabitun dynasty.

The Almohad Caliphate and Reconquista

While the Almoravid control over al-Andalus disintegrated, Moorish taifas once again sprang up to fill the power vacuum, this time headed by influential Andalusian families who shared cultural ties with the rest of Iberia (including the Christian north). But this status quo shared by the Iberian Moors was pretty short-lived, with yet another invasion from North Africa – led by the Almohads (al-Muwaḥḥidūn – ‘the unifiers’).

The Almohads had already established their Caliphate over most of Maghreb (by 1159 AD), by defeating their Almoravid predecessors. After settling their dominance in North Africa, they crossed into Iberia with the casus belli of dealing with the remaining ‘Almoravid-allied’ realms.

By circa 1173 AD, the Almohads conquered much of Muslim Iberia – an impressive feat considering that most of their army was originally tribal in nature. However, just like the Almoravids, the tribal scope was complemented by a professional force consisting of Africans, ex-Murabitun units, religious orders of mutatawwi’a warriors, and even small groups of fighters from the Arab Babu Hilal tribe, Turks, and Kurdish refugees.

The elite section of the army comprised the huffaz, sons of tribal leaders who were trained for warfare, rumat archers, and a guard unit known as abid al-makhzan (possibly having African recruits). It should be noted that this time period was politically charged, especially with the confident northern Christian Iberian kingdoms adopting an assertive stance on their southern Muslim neighbors.

In consequence, the very syncretic element of al-Andalus was starting to unravel due to religious differences and even discrimination on both sides. Moreover, the rigid tenets of the Almohads forced many of the rich Mozarabs (Christians living under Moorish rule) and Andalusian Jews to migrate to the north. The symbolic Cordoba was also relegated to a provincial city and its eminent place as the capital of al-Andalus was taken over by Seville.

Over the decades, the seemingly fanatical stance of the Almohads softened in Iberia, possibly because al-Andalus was ruled as a province by the pliable governors of the Caliphate centered in Morocco. Furthermore, in some cases, the Iberian Moors began to occasionally enact truces with their Christian neighbors, as means to autonomously protect themselves while also providing (sometimes unintentionally) strategic advantages to their opponents.

However, the overarching religiopolitical force of the Reconquista was hard to ignore for even the most broad-minded of the Andalusian Moors. To that end, one of the momentous episodes in the history of Iberia (Spain and Portugal) came in the renowned Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, where the Almohad army was handed a decisive defeat by a Christian alliance of Castile, Navarre, Aragon, and Portugal (supported by Crusaders, Military Orders, and French volunteers), in 1212 AD.

And starting from the 1230s, the Moors of al-Andalus, now in undoubtedly strategic retreat, continued to lose their important cities in a piecemeal fashion to the Christian offensive, finally culminating in the capture of Seville itself in 1248 AD.

Their overlords – the Almohads themselves also suffered a series of setbacks from a palace coup, political machinations, and territorial losses, which led to further fragmentation of civic control over al-Andalus, ultimately resulting in their own demise in Morocco by circa 1269 AD.

Granada – The Last Islamic Bastion of Al-Andalus

The power vacuum in 13th-century Morocco was filled by the Marinid dynasty who had no claim (or even the resources to fight) over al-Andalus. Around the same time, the Christian offensive had all but taken over the remaining taifas of the Iberian peninsula – and the only major parcel of land in al-Andalus that was nominally independent belonged to the Emirate of Granada.

Ruled by the Nasrids, who originally descended from the Arab Banu Khazraj tribe, the dynasty had familial ties to the Andalusian frontier warriors. However, in spite of their celebrated lineage (among the Iberian Moors), the state was simply not strong enough to withstand the impending Christian assault in the 13th century.

As a result, the rulers chose an initial political solution in the form of a tributary state that accepted the titular suzerainty of the Kingdom of Castile. This ‘makeshift’ truce with its Christian neighbors (that was occasionally broken by both sides) along with the natural barrier of the Sierra Nevada on its northern border allowed the Emirate of Granada to maintain both its political and religious autonomy – a status quo that was integral to its very survival.

Added to that was a dash of Moorish innovation in the fields of observant military, fortified defenses, and dynamic economy, thus allowing the Emirate to endure as the only Muslim state in medieval Western Europe for over 250 years (1230 – 1492 AD).

To that end, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the state depended on its various heavily fortified positions and castles (many overlooking strategic mountain passes) that were manned by thagri (warriors) under the leadership of an elite military class much akin to the contemporary knights of Europe.

The Emirate also maintained a standing army – jundi mutatawwan, supported by the famed almogaver light horsemen, Berber mercenaries and ghazat volunteers, and even a heavily armored Christian guard unit (often recruited from the north). Furthermore, the city of Granada also had a militia of its own headed by the sahib al-shurta.

By the early 14th century, the cultural ties shared by Granada and the rest of Iberia rubbed off on the dressing and equipment style of the elites, resulting in similar armor types and weapons flaunted by both the Iberian Christian knights and Granadian Muslim heavy horsemen – including mail hauberks, lances, and horse barding.

However, over the period of decades, as enmity between the states arose (sometimes due to audacious military ventures on the part of both Granada and Castile), the Emirate reverted to relying on the Berbers – thereby ‘importing’ more North African influence, like the adoption of lighter armor.

On the political front, Granada projected itself as the last refuge of the Iberian Muslims, thereby rather increasing its manpower (and economic output) with of help of the refugees escaping from the north. Incredibly enough, the capital was also financed by the Genoese bankers with a vested interest in the Mediterranean trade networks and even routes going into sub-Saharan Africa.

Thus the lower economic corridor of al-Andalus was momentarily revitalized, with commercial and military centers like Malaga, Guadix, Rhonda, and of course Granada itself. However, the Emirate suffered a big economic blow when the Portuguese successfully opened direct trade routes to Africa and its sub-Saharan regions.

But the fate of the Emirate of Granada was ironically sealed by not a venture but a marriage – the Christian matrimony between Ferdinand II and Isabella I, which resulted in the union of the Kingdoms of Aragon and Castile in 1469 AD. The united Christian front opened once again, this time with the concerted aim of vanquishing any Muslim political entity on the Iberian peninsula.

Thus the Granada War started in 1482 AD and was waged for ten bloody years. Finally, in spite of a stubborn defense exhibited by the Granadians, the Emirate, and its last Muslim ruler Muhammad XII unceremoniously surrendered in 1492 AD to the Los Reyes Católicos (‘The Catholic Monarchs’).

The Decline – Expulsion of the Iberian Moors

After more than 780 years of existence in Iberia, the Moors of al-Andalus lost both their political state and status – and thus were faced with the scenario of total obsolescence (in a Catholic realm). On the Christian side, while the Spanish Inquisition was sanctioned in 1478 AD as an initial measure to root out heretics, it morphed into a Papacy-backed powerful instrument of persecution aimed at Andalusian Muslims and Jews.

So while, a statute from 1492 AD under the conditions of terms of surrender, officially allowed Muslims (identified as Moriscos) freedom to pursue their religion and businesses, mass-conversion pogroms were already initiated in Castile by 1499 AD. This led to an uprising among the Moors in circa 1499-1500 AD, which rather provided a pretext for the revokement of their religious rights by the Catholic monarchs.

By 1502 AD, Castile officially decreed the forced conversion of Muslims in its own territory, while Aragon and Valencia, although relatively lax in their attitude towards the Andalusian Moors initially, passed the same decree in 1526 AD due to mounting political pressure.

Consequently, over the passage of decades, a considerable number of Andalusians, equating to hundreds of thousands, migrated or were expelled to Africa. Another royal decree passed in 1609 AD, better known as the Expulsion of the Moriscos, resulted in the further eviction of thousands of Moors (although some of them managed to return to Iberia in secret).

And lastly, in 1727 AD, by which time, the overwhelming majority of the population of Spain and Portugal were already Christianized, state-sanctioned persecution directed at the Moriscos was initiated. This accounted for the proverbial ‘final nail’ on the almost thousand-year-old legacy of the Moors as a separate religio-cultural group in the Iberian peninsula.

Online Sources: Britannica / Spanish-Fiestas / National Geographic

Book References: The Moors: The Islamic West 7th-15th Centuries AD (By David Nicolle) / History of the Moors of Spain (By Florian)

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork, or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "Moors: The Fascinating Muslim Rulers Of Al-Andalus"