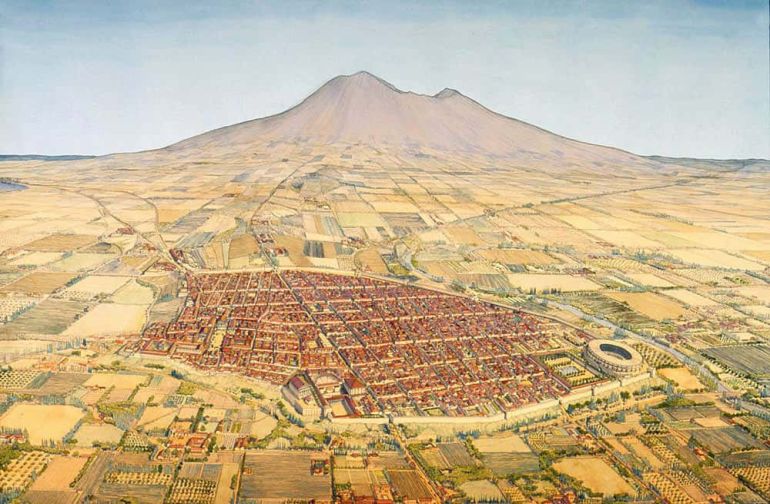

Pompeii, the ancient Roman town-city near modern Naples, boasted an assortment of baths, houses, temples, public structures, graffiti, frescoes, and even a gymnasium and a port. But more than any of these ancient avenues, the city is best known for its brush with disaster for over 400 years, after its rediscovery way back in 1599 AD. In fact, the site of Pompeii has been a popular tourist destination for over 250 years – thus merging an unfortunate episode of history and the innate level of human curiosity.

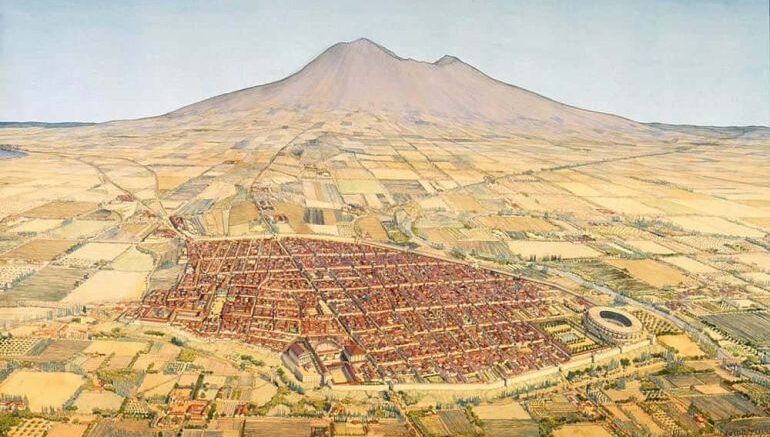

However, beyond just the ‘popular’ impact of the disaster, there was the historical city of Pompeii – a thriving Roman settlement with over 11,000 in population. To that end, in this article, we will aim to present the history, reconstruction, and architecture of this ancient city that was influenced by various people of Italy, including the Oscans, Etruscans, Greeks, Samnites, and Romans.

Contents

The History of Pompeii

The Origins of Pompeii and its Etymology (circa 8th Century – 5th Century BC)

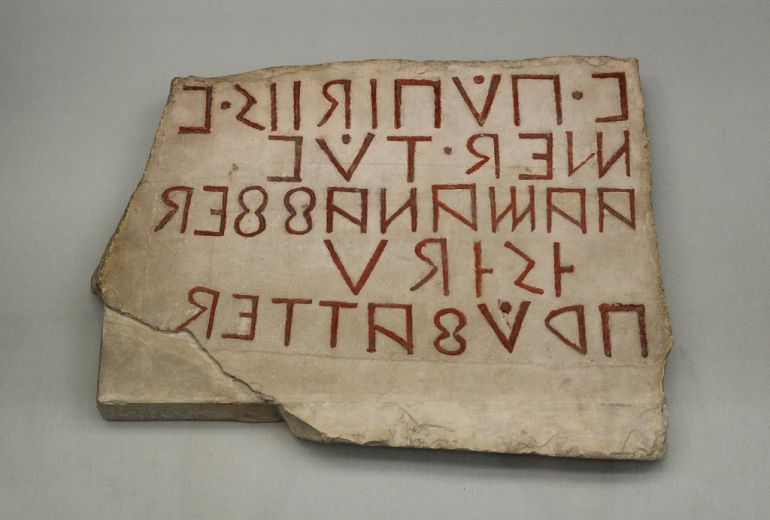

Delving into the origins of Pompeii, the first known evidence of proper habitations in the area (southwestern part of Italy) possibly harks back to the Bronze Age. Fast-forwarding to centuries later, a juncture close to the mouth of River Sarno was occupied by five villages of the Oscans, an Italic people from the 8th century BC.

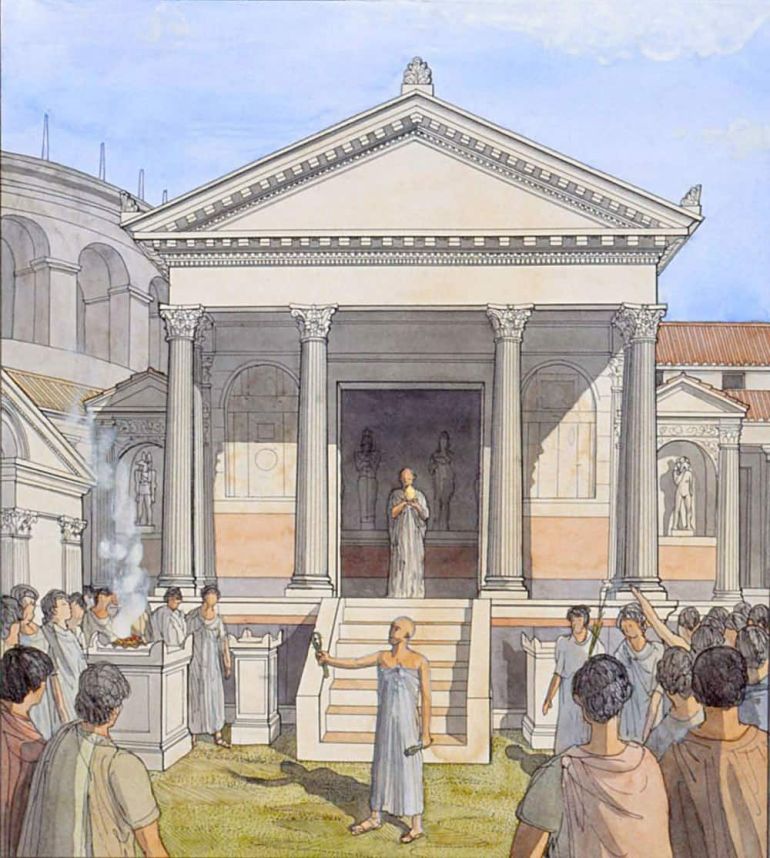

By Circa 740 BC, the area came under the influence of the Greeks – who were known to have established their trading colonies in the Campania region. And it was the Greeks who probably endowed Pompeii with its first urban character, by building a Doric Temple that later became the focal point of a forum and introducing the cult of Apollo. Over time, Pompeii, with its advantages of a favorable climate and rich volcanic soil, was transformed into a safe port used by maritime powers like the Greeks and the Phoenicians.

In terms of etymology, it appears that Greeks already observed the potent nature of Vesuvius, as can be discerned from their myth (interpreted by the Romans) that describes how Hercules defeated earth giants in the Phlegraean Plain (or ‘plain of fire) on route to Sicily. Thus the nearby town of Herculaneum may have been named after this mythical narrative of Hercules.

Furthermore, according to one ancient Roman account, Pompeii comes from pumpe – the procession that commemorates the hero’s victory over the giants. However, on the academic side of affairs, many scholars believe Pompeii is possibly derived from pompe – meaning ‘five’ in Oscan, thus once again alluding to the original five villages on the site. Yet another hypothesis states that the name is derived from gens Pompeia – the Romanized family name.

In any case, reverting to history, by the 6th century BC, the local Italic inhabitants and the Greek colonists had merged into a single community of Pompeii. This strengthened nature of the Pompeii urbanites is also mirrored by the tufa city walls that guarded the settlement.

However, by the late 6th century (circa 524 BC), the Etruscans arrived in the region and possibly took commercial control of the city, while preserving its political autonomy – thereby making Pompeii one of the members of the Etruscan League of Cities.

The settlement, by then, already functioned as a regional trading hub with its typical urban character comprising a market square (forum), necropolis, and limestone walls. But the Etruscan influence on Pompeii was cut short after just five decades, with the Greek city of Cumae, allied with Syracuse, inflicting a heavy naval defeat on the Etruscans in the Bay of Naples, in circa 474 BC.

The Samnite Interlude (circa 424-290 BC)

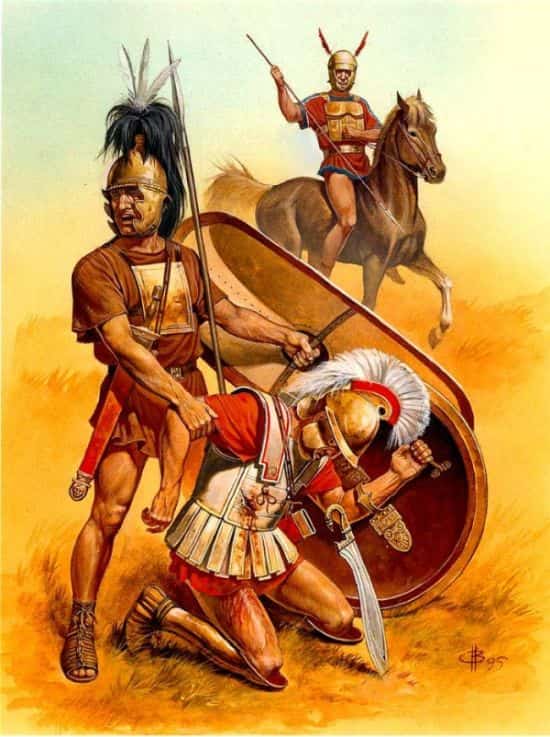

Quite intriguingly, even the ‘newfound’ Greek political might in Pompeii was short-lived, with the Campania region, in turn, being invaded by the Samnites, a warlike Italic people originally hailing from the south-central part of the peninsula.

The city itself had already begun to show signs of deterioration since circa 450 BC, with the dilapidation of various urban areas and a lack of offerings made at the Temple of Apollo. And possibly, by circa 424 BC, Pompeii was wholly conquered by the Samnites, and the settlement, along with other proximate cities like Capua and Nola, gradually adopted the characteristics and architectural styles of their Italic overlords.

To that end, while the Samnites were known for their proclivity toward martial pursuits, archaeological evidence has also alluded to the cultural and architectural achievements of these people. For example, recent excavations have revealed the remains of a full-fledged Samnite temple within the confines of Pompeii.

Dated from circa 4th-3rd century BC, the structure was dedicated to Mefitis, the Samnite equivalent of Venus, who was also venerated in volcanic areas and swamps as the personification of poisonous fumes emanating from the earth.

In addition to the temple, archaeologists have also found a Samnite tomb, along with objects and artifacts, like lamps, terra cotta work, seashells, coins, and a bath. The latter ‘bath’ feature was possibly used for what historians have called ‘sacred prostitution’. In the ritual, the betrothed women were required to lose their virginity for a coin before their actual marriage.

The Roman Pompeii (circa 290 BC – 62 AD)

Interestingly enough, in spite of the political control of the Samnites over Pompeii in the 4th century BC, the era also brought forth nascent levels of Roman influence in the city – possibly because it hosted a part of the Roman army during the Latin Wars, circa 343 BC.

And by the time of the Third Samnite Wars (298–290 BC), residents of Pompeii sided with the ascendant Romans who ultimately triumphed over the Samnites – resulting in the hegemony of the Roman Republic in the Italian peninsula. Consequently, Pompeii was awarded the status of a socii (akin to an allied state with semi-autonomous powers and Roman protection).

Over the period comprising the next centuries, Pompeii was transformed into an important port in the Bay of Naples. The trading hub was also noted for exporting goods such as garum, olives, figs, cherries, and apricots, along with vegetables like onions and cabbages.

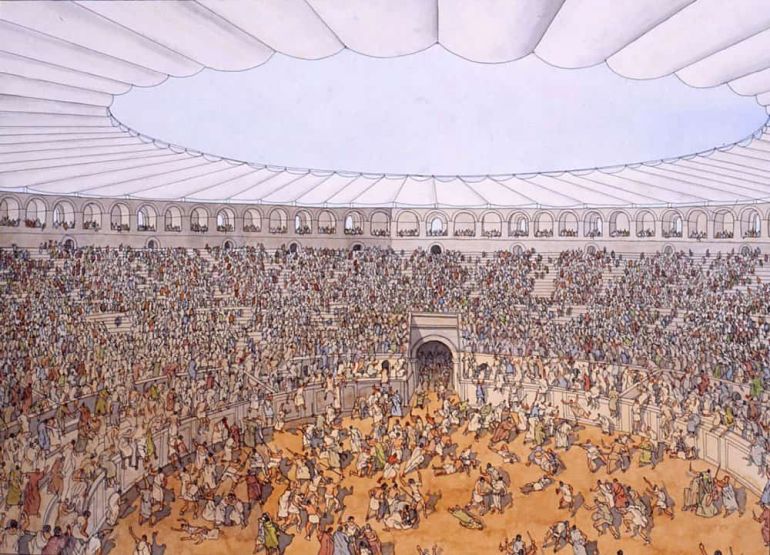

But the characteristic item associated with the thriving city arguably relates to wine – the product of the rich volcanic soil that provided the ideal conditions for growing grapes. Additionally, Pompeii served as the importing point for various exotic commodities, including sandalwood, spices, silk, and even foreign animals for the arena.

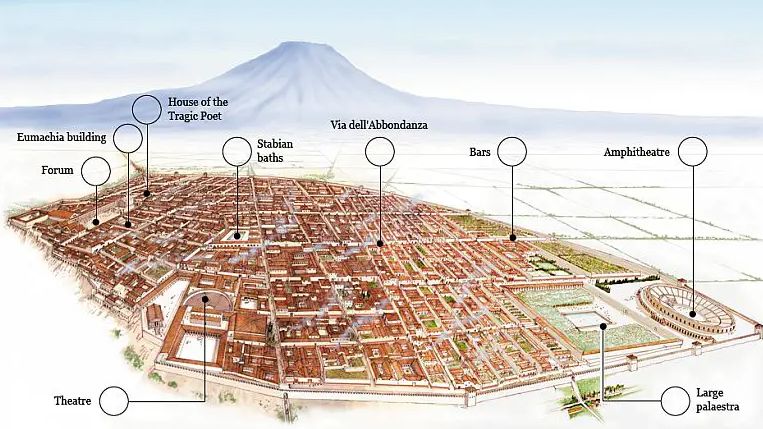

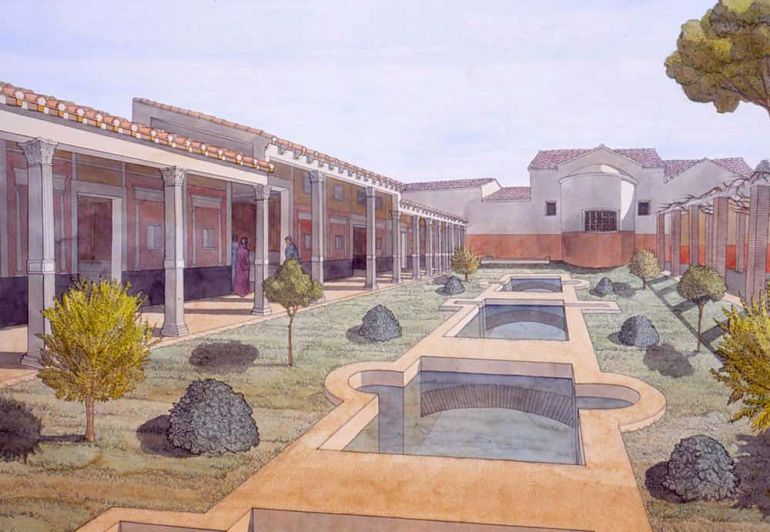

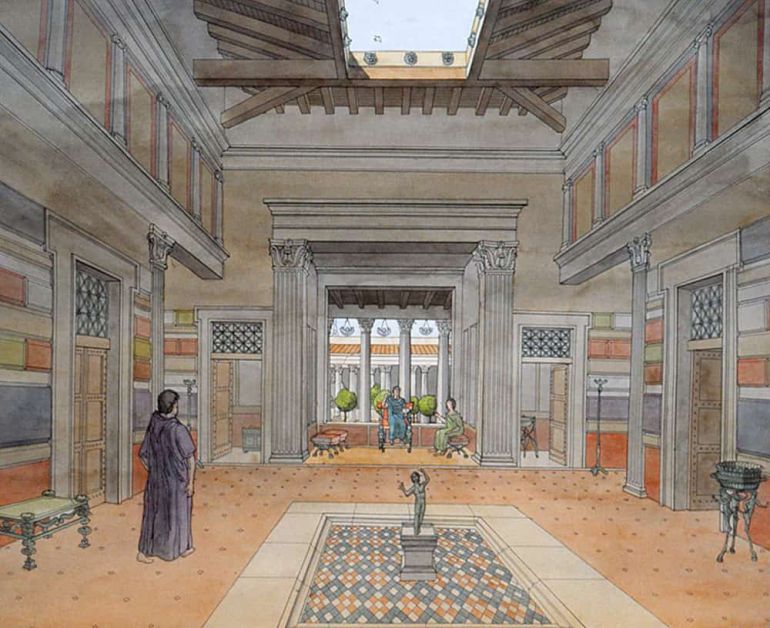

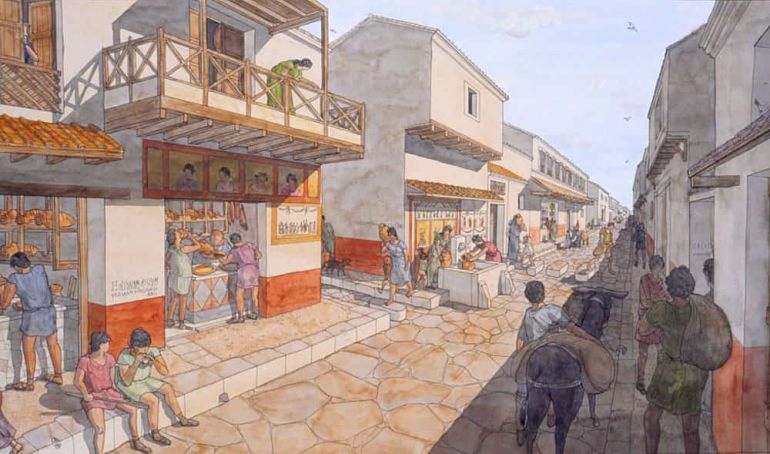

The opulent mercantile scope was complimented on the architectural level, with the erection of bigger walls with double parapets, paving of wider streets in most parts of the settlement (that were innovatively repaired by using molten iron), and building of various structures ranging from shops, taverns, thermal baths, aqueducts, schools to launderettes, brothels, slave-quarters, domus (large Roman residences), and large villas (many dating from the 2nd century BC, showcasing their Greco-Roman styles).

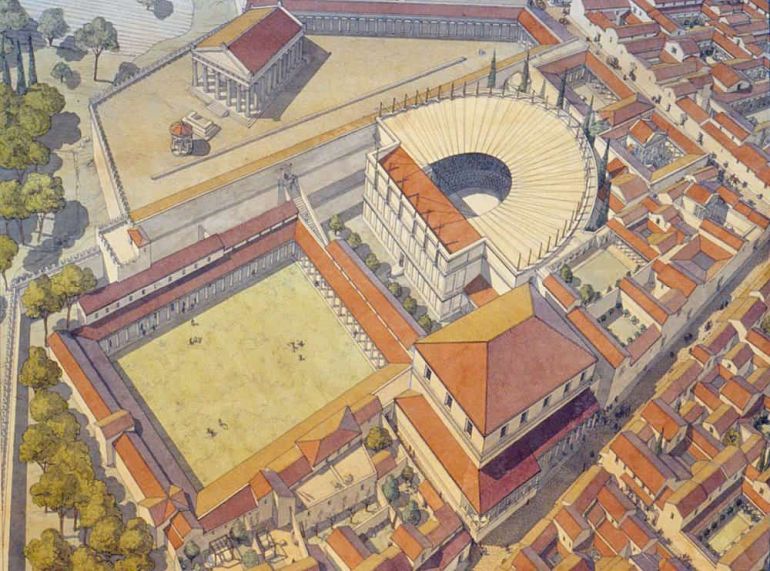

The main Triangular Forum of the city (named after its geometric triangle shape) also underwent a revitalization, with the construction of the Basilica (courthouse), Temple of Jupiter, and the Macellum (provision market). Moreover, Pompeii was known as a resort and a popular retreat for the upper classes from across the Roman Republic.

On the political side of affairs, in spite of Pompeii’s allied status with Rome which was even maintained during the mercurial times of the Second Punic War, the inhabitants of Campania (including Pompeii) finally revolted against the Roman Republic circa 91 BC – due to their perceived lack of rights when compared to Roman citizens. This led to the Social Wars (91-88 BC), an event that once again resulted in a Roman victory.

However, as a means to assuage the semi-autonomous cities and polities, the Republic offered Roman citizenship to all its Italian allies, thereby resulting in the complete Romanization of Italy. As for Pompeii, the city was successfully besieged by Sulla during the war.

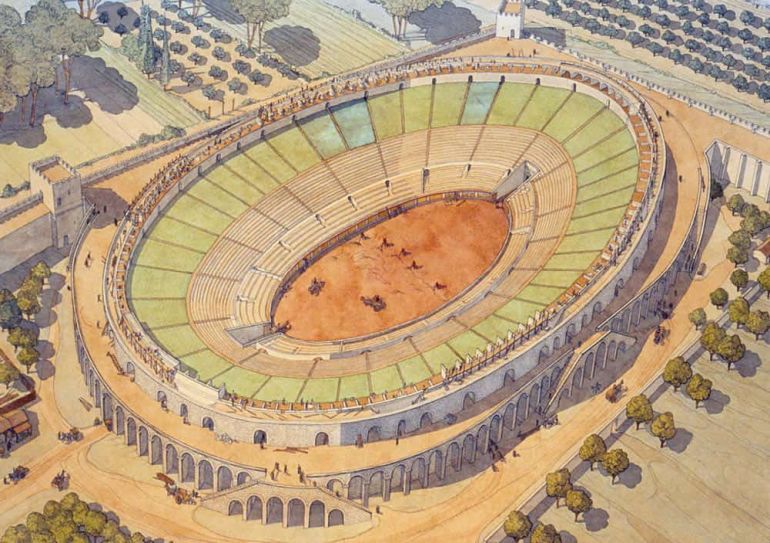

Consequently, it came into the fold of the Roman authority and was settled by around 5,000 of Sulla’s veteran legionaries. From that point on, Pompeii was ruled as a Roman colony called Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum – and the town was further revitalized with a formation of a local senate and the building of an Amphitheater.

The Wrath of Vesuvius (62 – 79 AD)

The above animation made by the Zero One team was showcased at a 2009 exhibition named aptly as the ‘ A Day in Pompeii’, in the Melbourne Museum. Suffice it to say, the exhibition used 3D renderings to present a more accurate picture of the impending disaster that took place in 79 AD, and its baleful effects in the span of 48 hours surrounding the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

Pompeii (and the region of Campania), known for minor seismic activities, was afflicted by a massive earthquake in 62 AD. As a consequence, a great number of structures, including temples, roads, and houses, collapsed, while fires and smoke made their severe presence felt in many corners of the city.

In spite of the ensuing anarchy and a significant number of casualties, parts of the infrastructure and forum were rebuilt, including the Central Thermal Baths. Many new structural projects were also initiated, like the Temple of Vespasianus and the Temple of Lares.

And while Pompeii experienced increasing degrees of seismic activities in the following years, the catastrophe struck in the year 79 AD, when Vesuvius erupted. Shrouded by displays of smoke, fire, explosions, and layers of pumice particles, the city was soon covered in flecks and fragments of ash discharged by the eruption.

And while the buildings were already beginning to collapse from the weight of such heavy deposits, the ‘shock-and-awe’ came forth hours later – in the form of destructive waves of superheated volcanic matter and gas (pyroclastic flows) from the imploding cloud over the volcano. According to some studies, it might have been the heat rather than asphyxiation (caused by ash) that resulted in many untimely deaths inside the buildings.

Pliny the Younger described the scene of the disaster in letters written to Cornelius Tacitus, a friend of his. Written a few years after the event, one of the passages of the second letter reads like this –

Ashes were already falling, not as yet very thickly. I looked around: a dense black cloud was coming up behind us, spreading over the earth like a flood.’ Let us leave the road while we can still see, I said,’ or we shall be knocked down and trampled underfoot in the dark by the crowd behind.’ We had scarcely sat down to rest when darkness fell, not the dark of a moonless or cloudy night, but as if the lamp had been put out in a closed room.

You could hear the shrieks of women, the wailing of infants, and the shouting of men; some were calling their parents, others their children or their wives, trying to recognize them by their voices. People bewailed their own fate or that of their relatives, and there were some who prayed for death in their terror of dying. Many besought the aid of the gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left, and that the universe was plunged into eternal darkness for evermore.

Reconstruction of Pompeii

However, as we mentioned before, beyond just the ‘popular’ impact of the disaster, there was the historical city of Pompeii – a thriving Roman settlement with over 11,000 in population. In fact, by the late 1st century AD, Pompeii was known for its export of wine and its resort-like characteristics (which explains the bevy of ancient ‘holiday homes’ in the city). To that end, the folks over at Altair4 Multimedia have concocted a superb animation (above) that aptly presents the historicity of Pompeii, before it was ‘marred’ by catastrophic events.

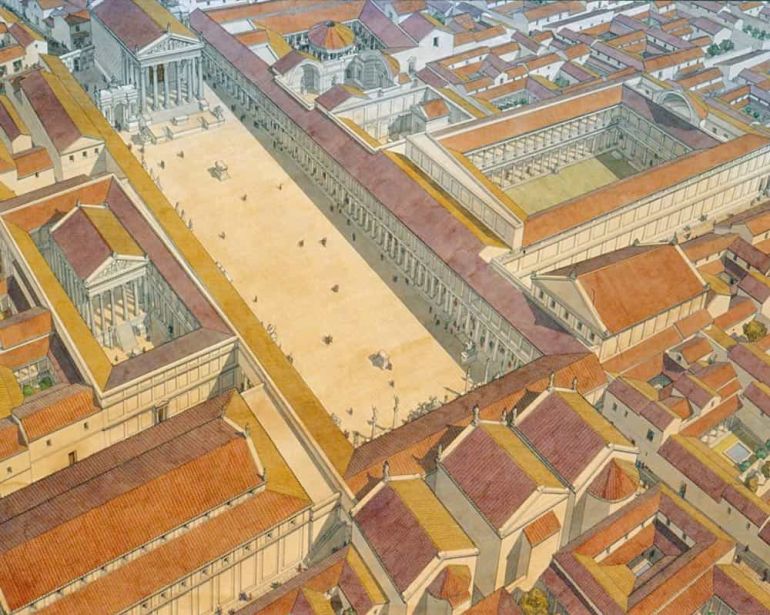

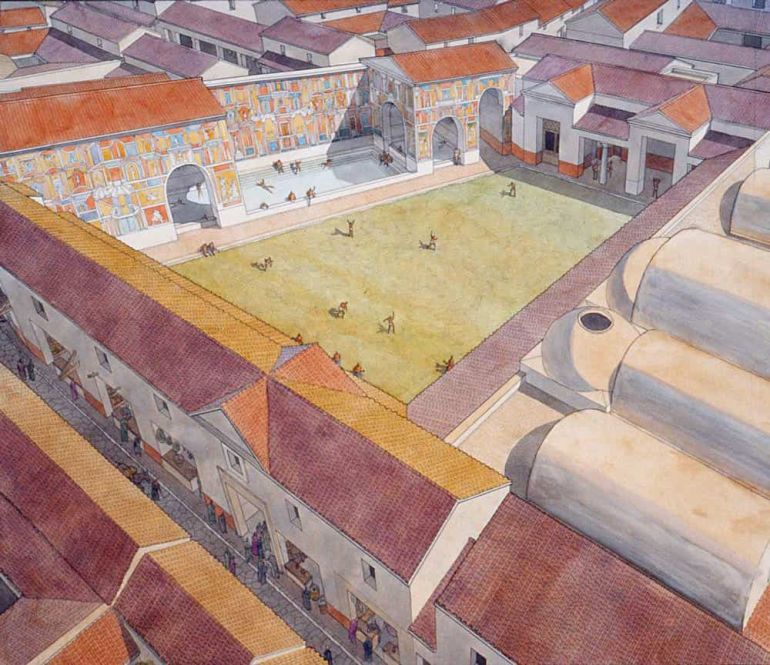

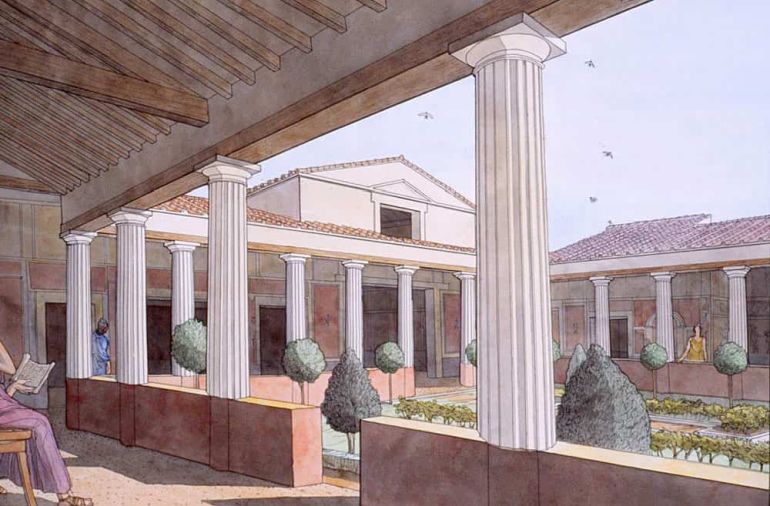

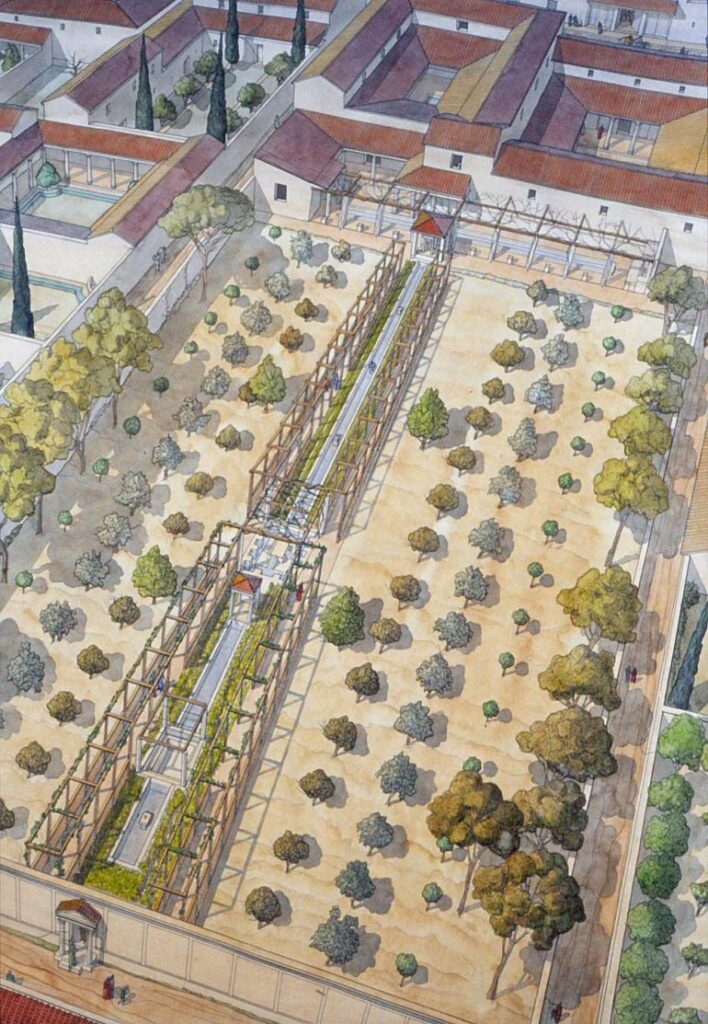

A series of watercolor illustrations made by noted French archaeologist Jean-Claude Golvin also captures the various houses, public areas, and overview of the thriving city of ancient Pompeii.

Researchers have also been able to recreate a Roman domus (large house) inside Pompeii that existed before the natural disaster of 79 AD. Envisaged as a continuation of the Swedish Pompeii Project (now overseen by Sweden’s Lund University), the authentic reconstruction project was led by archaeologists Anne-Marie Leander Touati – with the experts utilizing 3D scanning and even drone technologies.

Be the first to comment on "Ancient Pompeii: History and Reconstruction"