Introduction

The subject of Spartans has been much discussed and showcased in the realm of popular culture. And while some of them have a historical basis, a few other sides are just instruments of exaggeration. In any case, we should start off with what might seem fantastical, but was possibly true – and it pertains to how Spartan babies were actually inspected at their birth, with the perceived ‘unworthy’ ones (or at least a few of them) being left abandoned on nearby hillsides.

Interestingly enough, archaeology has not brought forth clear-cut evidence of such a practice, although researchers have discovered remains of adults (possibly criminals) on Spartan hillsides. Reverting to history, Spartan boys were given a diet of frugal food and sometimes bathed in wine thinned with water. Such contrasting practices were believed to mold both his fortitude and physique as per the requirement of a Spartan warrior.

And finally, relating to etymology, the name ‘Lacedaemonian’ (often used as a synonym for Spartan) was first attested in the Linear B – syllabic script of the Mycenaeans. In the Roman era, the term Lacedaemon was often used as a generalized term to define the geographical or political domain of Sparta.

Meanwhile ‘Sparta’ was possibly used to specify the core region in and around the city of Sparta (comprising Laconia) by the Eurotas River, in southern Greece. Hence the population who resided within the larger domain (as opposed to the core region of Laconia) was also referred to as the Lacedaemonians.

Contents

Society and Politics of the Spartans –

The ‘Militaristic’ Origins of Sparta

The word ‘Lacedaemon’ also comes from Greek mythology, wherein Lacedaemon was said to have been the son of Zeus and the nymph Taygete. Lacedaemon, in turn, married Sparta, the daughter of Eurotas, and named the country after himself and the founded city after his wife.

However, beyond the narratives of Greek mythology, archaeologists have found pottery-based evidence near Sparta (city) that dates from the middle Neolithic period. But, interestingly enough, as opposed to the older Neolithic legacy of Athens, the city of Sparta itself was probably a ‘new’ settlement that was founded by the Greeks in circa 10th century BC.

In any case, the militaristic ways of the ancient (sometimes categorized as warlike Dorians by ancient authors) soon handed them dominion over the populace of Messenia. As a result, Sparta boasted some 8,500 sq km of territory (in the lower Peloponnese) – which made their polis (city-state) the largest in the 8th century BC timeframe of Greece.

But, as with many episodes of war brewing their fair share of instability, Sparta was often embroiled in revolts and insurrections during this period (8th – 6th century BC) – mainly due to their rigid social order, discussed later in the article.

The Political Ascendancy of Ancient Sparta

The Spartans achieved what can be termed political supremacy in the lower Peloponnese by defeating and absorbing the state of Messenia during the Second Messenian War (685-668 BC). From thereon, the domain of Sparta stretched across Laconia and Messenia.

Consequently, Sparta became one of the militarily powerful city-states of ancient Greece. By 505 BC, the Peloponnesian League was formed – an alliance of Greek city-states (including Corinth and Elis) headed by Sparta that allowed it to establish a political hegemony in the Peloponnesus peninsula.

In the next few decades, Sparta, in spite of losing to Tegea in a frontier war, boasted its potent military – often heralded as the strongest land-based force in all of Greece. By the late 6th century, the Spartans aided the Athenians in getting rid of their tyrants, while also bearing the brunt of the Persian wars and invasion at the Battle of Thermopylae (circa 480 BC).

These events rather reinforced the notion of Spartan military supremacy in Greece during the 5th century BC. However, the rising rivalry between Athens and Sparta soon escalated into the disastrous Peloponnesian Wars that raged intermittently from circa 460 to 404 BC, thereby gradually puncturing the political powers of both city-states.

The Stringent Social Stratification

In spite of their namesake, the Spartans (the original inhabitants of Sparta and its core region Laconia), also called Spartiates (or Homoioi – meaning ‘those who are alike’), formed a minority in the region of Laconia and Messenia by the late 4th century BC.

Yet they were the only ones who were considered free Spartan citizens of the city-state with full-fledged political rights. The larger free but ‘non-citizen’ group pertained to the conquered populace of Messenia, and they were called the perioikoi. And in spite of their majority, the perioikoi possessed almost no political rights and yet were liable to be drafted into the army.

The third social order pertained to the helots (heílotes), basically constituting the subjugated population of Laconia and Messenia. Described as slaves by some ancient authors (while defined as slightly above slaves by others), the helots were forced to work as serfs on the agricultural lands of the Spartans.

During the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), given the chronic manpower shortage faced by Sparta, many of these helots were actively trained and conscripted by the army. And by the end of the war, some of the helots were even freed and they formed a fourth social order – neodamōdeis.

Befitting their better rights, the richer of these neodamōdeis were offered lands in the border areas of the Spartan state. But the main reward probably related to their newfound ‘freed’ status – a very important social marker in ancient Spartan society.

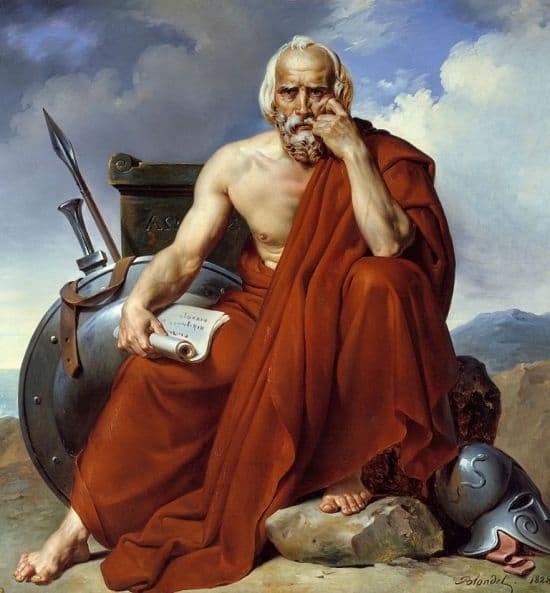

The Laws of Lycurgus

Now given the nature of the harsh social order, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Sparta faced frequent revolts from the subjugated sections of their population, mainly entailing the helots. And while not documented in detail, it is highly probable that mirroring the political upheaval in Athens circa the 8th and 7th centuries BC, the Spartans faced their own ‘version’ of civil strifes and lawlessness – as mentioned by both Herodotus and Thucydides.

Furthermore, hamstrung by such insurrections, the Spartans also suffered a few defeats at the hands of other Greek city-states, with one famous example relating to their loss to Argos at the Battle of Hysiae in 669 BC. Consequently, the disruptions and defeats resulted in a set of law-based reforms covering both the social and political aspects of the ancient Spartan state.

This series of laws was often ascribed to the semi-legendary lawgiver Lycurgus. As such, he was credited with a myriad of amendments that applied to a vast range of civic laws – from marriage, distribution of wealth and land, constructing houses, and even sexual conduct.

One pertinent law apparently prescribed how the Spartan citizen was barred from trading and manufacturing, which, in turn, allowed the perioikoi to step in like the proverbial middle class. In essence, the perioikoi emerged as the mercantile class with stable economic backgrounds, while the Spartans retained their landholdings and estates (that were worked upon by the helots). But the most famous of Lycurgus’ reforms was arguably the agoge – the rigorous military training program for Spartan boys.

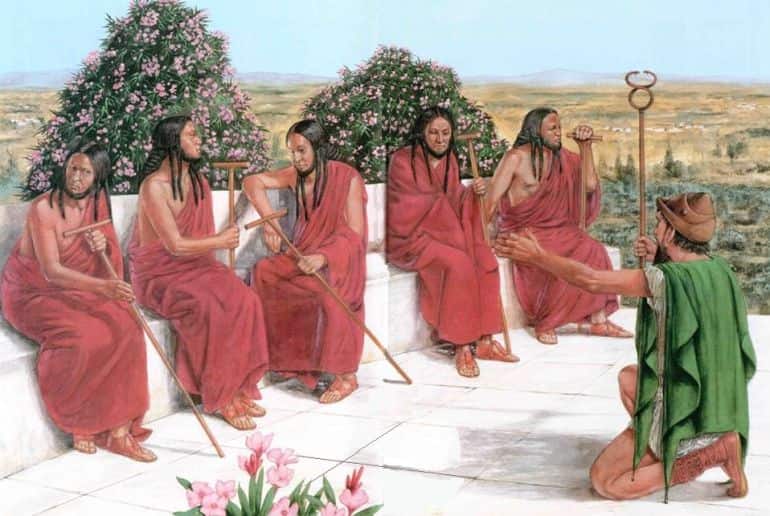

The Political System of Spartans

A pretty unique political system of Sparta equated to two kings instead of one. And while kingship was hereditary, the kings, who also performed duties as priests of Zeus, had to come from two different families of Spartiate (Homoioi) backgrounds. During times of war, one of the kings was given the responsibility of leading the army, while the other stayed back for governing duties.

One pertinent example would relate to the Battle of Thermopylae, during which King Leonidas (Leonidas I) of the Agiad house led the Spartan host, while the co-ruler Leotychidas of the Eurypontid house stayed back. The latter, however, played his military role after the death of Leonidas, by defeating the Persians on the coast of Asia Minor – at the Battle of Mycale in 479 BC.

The oligarchic governance of Sparta was also aided by a council of elders, known as the gerousia. This council was composed of 28 individuals, all above 60 years of age, who were elected for life – and were probably members of the royal household. The body led and facilitated the citizen assembly known as the appella (or ecclesia), which was held once a month and was open to all free citizens of Sparta (still comprising a minority of the overall population of Sparta or Lacedaemon).

The executive, civic, and criminal decisions were also handled by a committee of five ephors (ephoroi) chosen by the damos – the representative body of the Spartan citizenry. These ephors could only serve for a year and were liable to accompany the king on war campaigns.

Over time, it is highly possible that the constitutional power of Sparta passed on to the hands of the ephors and gerousia, while the kings were only figureheads who were expected to showcase their generalship during times of war.

The Spartan Women

The Spartan women of Spartiate backgrounds enjoyed relatively high degrees of both freedom and respect, especially when compared to other contemporary ancient Greek realms. Pertaining to the first, the girls from their young age were given equal nourishment as boys and were allowed to both exercises and take part in athletic competitions. This possibly even included the Gymnopaedia (‘Festival of Youth’), wherein the youths took part in running, wrestling, and even javelin throwing.

Furthermore, interestingly enough, from the societal perspective, child marriage was forbidden by the Spartans, which in turn increased the average marrying age of women to late teens or early 20s. From ancient sources, it can also be surmised that the literacy rate among Spartan women was comparatively higher than in other Greek city-states, which, in turn, allowed them to take part in public discourse and discussions. But the most intriguing part about the Spartan woman arguably relates to her economic power in the ancient world.

As we will discuss later in the article, Spartans (Spartiates) tended to face a chronic shortage of manpower (males), due to the attritional nature of wars coupled with the low birth rate. Accordingly, it has been hypothesized that by the late 5th century, almost 2/5th of the state’s wealth was passed on to the hands of women, thereby making some of them the richest members of society.

Military of the Spartans –

The Demanding Agoge and the Spartan Boys

The agoge was an integral part of the Spartan warrior culture that combined both education and military training into one rigorous package. As noted by Prof. Nick Secunda, it was mandated for all male Spartans (of Spartiate background) from the age of 6 or 7 when the child grew up to be a boy (paidon). This meant leaving his own house and parents behind and relocating to the barracks to live with other boys.

Interestingly enough, one of the very first things that the boy learned in his new quarters was the pyrriche, a sort of dance that also involved the carrying of arms. This was practiced so as to make the Spartan boy nimble-footed even when maneuvering heavy weapons. Along with such physical moves, the boy was also taught exercises in music, the war songs of Tyrtaios, and the ability to read and write.

By the time, the boy grew up to be 12, he was known as the meirakion or youth. Suffice it to say, the rigorous scope was notched up a level with the physical exercises increased in a day. The youth also had to cut his hair short and walk barefoot, while most of his clothes were taken away from him.

The Spartans believed that such uncompromising measures made the pre-teen boy tough while enhancing his endurance levels for all climates (in fact, the only bed he was allowed to sleep-in in the winter was made of reeds that had been plucked personally by the candidate from the River Eurotas valley).

Added to this stringent scope, the youth was intentionally fed with less than adequate food so as to stoke his hunger pangs. This encouraged the youth to sometimes steal food; and upon being caught, he was punished – not for stealing the food, but for getting caught.

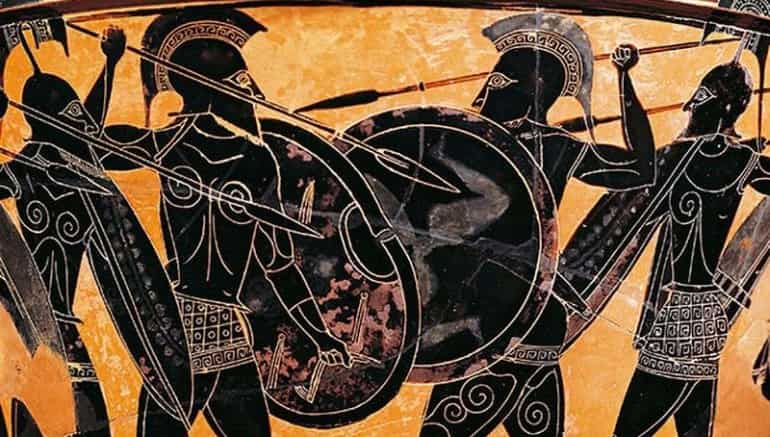

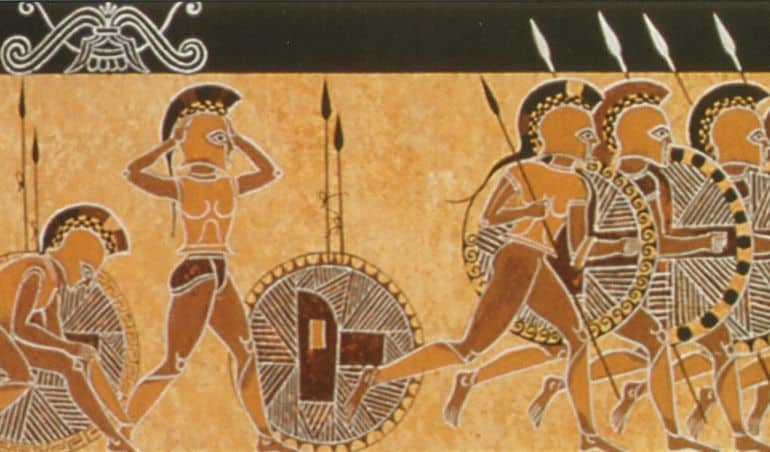

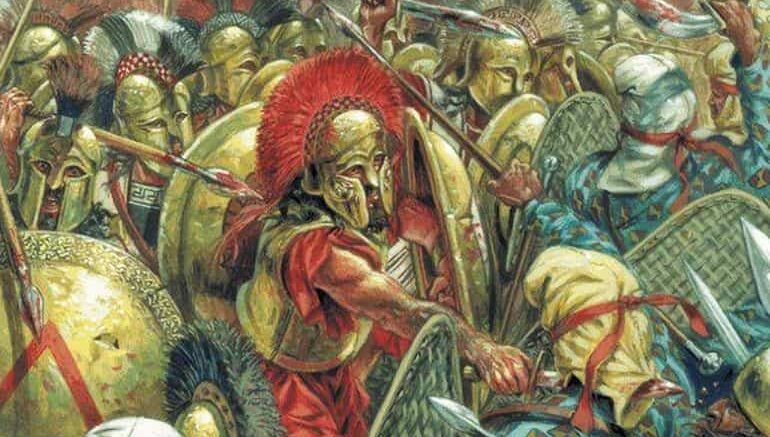

The Spartan Army – Hoplites

At the age of 18, the Spartan male was perceived as an adult citizen (eiren) of the state and thus was liable for full military service till the age of 60. For the Spartiates (Homoioi), this military service generally equated to being inducted into the ranks of the famed Spartan hoplites.

Now from the perspective of history, in spite of the popular imagery of Spartan soldiers fighting in mass formations, academia has not reached a consensus when it comes to their original battle orders.

However, what we know pertains to the unique ‘tribe’ system of ancient Greeks. This tribe system (with ties of the citizenry, not blood) was a natural evolution of the Greek society and military that required disciplined formations and trained men for protracted warfare. Such measures over time gave rise to the Greek hoplites, a class of warriors who were not really separate from the citizens themselves.

In essence, a Greek hoplite was a citizen-soldier who took up arms to defend or expand the realm of his city-state. And it should be noted that as a general rule, most adult males of the Greek cities were expected to perform military service. Thus the Greek hoplites, especially the Spartan warriors, were part of an ‘institution’ that fought in a phalanx formation where every member looked out for each other.

Consequently, the aspis shield was considered the most crucial part of hoplite equipment. For example, when the exiled Spartan king Demaratos was asked – why men are dishonored only when they lose their shields but not when they lose their cuirasses? The Spartan king made his case – ‘because the latter [other armors] they put on for their own protection, but the shield for the common good of the whole line.’

Furthermore, Xenophon also talked about the more tactical side of a hoplite phalanx formation, which was more than just a closely-packed mass of armored spearmen. He drew a comparison to the construction of a well-built house (in Memorabilia) –

…just as stones, bricks, timber, and tiles flung together anyhow are useless, whereas when the materials that neither rot nor decay, that is, the stones and tiles, are placed at the bottom and the top, and the bricks and timber are put together in the middle, as in building, the result is something of great value, a house, in fact.

Similarly, in the case of a phalanx of Greek (or Spartan) hoplites, Xenophon talked about how the best men should be placed both in the front and rear of the ranks. With this ‘modified’ formation, the men in the middle (with presumably less morale or physical prowess or even experience) would be inspired by the front-placed men while also being ‘physically’ driven forth by the rear-placed men.

Training and Military Prowess

Interestingly enough, popular depictions of ancient warfare frequently involve the pushing and shoving of the Spartan hoplites when they closed in with the enemy. Now while such a scenario was probably the credible outcome of two tight phalanxes clashing with each other, in reality, many battles didn’t even come to the scope of ‘physical contact’.

In other words, a hoplite charge was often not successful because the citizen soldiers tended to break their ranks (and disperse) even before starting a bold maneuver. As a result, the army that held its ground often emerged victorious – thus exemplifying how morale was far more important than sheer strength in numbers.

This alludes to why the courageous Spartans were considered lethal on the battlefield. Xenophon, in spite of being an Athenian, heaped his praise on the Spartans by calling them – “the only true craftsmen in matters of war”. To that end, it could also be argued that Spartan warriors, among all Greek city-states, were truly professional soldiers – by virtue of their full-time dedication to the art of war.

Simply put, the Spartan soldier was the product of the state-institutionalized training system (agoge) that encouraged a full-time fighting force. So while other Greek hoplites had to return to their fields after a period of service, the Spartan warriors had the advantage of focusing on their training, fortitude, and organization. That was because their agricultural economy was mostly driven by the labors of the helots, thus providing more time for the full citizens to drill in military service.

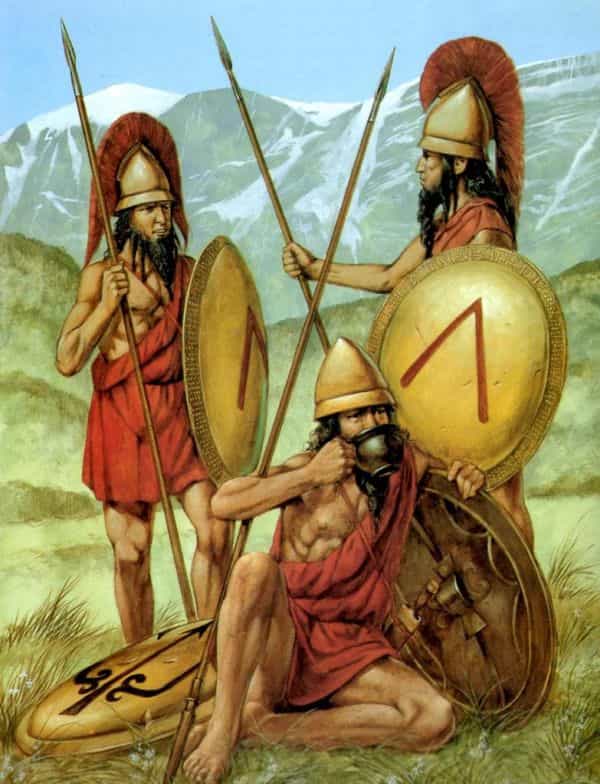

Spears, Shields, and Swords of the Spartans

The spear was the main offensive weapon of the Spartan soldiers, so much so that they were required to carry it during all times of a campaign. Most of these spears were made of ash wood, probably due to their longer grains that allowed for larger pieces – thereby having the advantages of both lightness and strength.

The leaf-shaped spearhead was made of iron, while the butt-spike was made of bronze (possibly a later design modification) so as to mitigate the dampness from the ground when the spear was rested upon it.

As for defensive equipment, in the period after the 6th century BC, the hoplite shield or aspis (commonly referred to as the ‘hoplon’) went through a structural modification – with the shield cover being embossed with a layer of bronze.

The supporting wooden (or leather) component underneath was also laminated, thus allowing for more curvature and strength. Suffice it to say, much like the Roman scutum, the aspis was used as a bashing weapon in close quarters – thus effectively making it an instrument of offense in spite of its core defensive nature.

And even beyond battlefield tactics, there was a symbolic aspect attached to the Spartan shield – so much so that it was considered (along with the spear) as the most important part of the Spartan panoply. Some of us might already know about Plutarch’s famous recounting of an incident where the mother says to his Spartan warrior son – ‘either [with] it [your shield], or on it’.

But rhetoric aside, the shield was given importance because of the equipment’s reach and coverage. So Spartan warriors who lost their shields on the battlefield were often punished afterward.

And as for swords, according to Prof. Secunda, by the late Fifth Century BC, Greek armies tended to discard their heavy body armor in favor of enhanced mobility. Interestingly enough, mirroring the very same period, the swords (known as xiphos) carried by the Spartan army got shorter – almost to the point that their length could be compared to daggers.

This might have had its tactical benefit, with the short length forcing the Spartan warrior to thrust his weapon at the torso and groin areas of his opponent, as opposed to the conventionally longer Greek sword that was often used to slash at the head.

The advantage for the Spartans pertained to the fact that the contemporary body armor was also (mostly) changed to lighter linothorax instead of the heavy ‘muscled’ cuirass – and thus a short sword could be used as an effective secondary weapon for inflicting thrusting injuries on the enemy.

And as with many Laconic phrases, there are literary tidbits put forth by Plutarch when it came to the exceedingly short swords of the Spartans During one instance when King Agesilaus was asked why Spartan swords are too short, he tersely replied – ‘because we fight close to the enemy’. In another episode, when an Athenian asked a Spartan why his sword was so short, he retorted – ‘it is long enough to reach your heart.’

Singing and Sacrifices

Despite their ‘laconic’ ways, symbolism and superstitions played a big role in the Spartan military. The ritualistic scope is quite evident from the way the Spartan kings sacrificed animals before the start of any military campaign beyond Sparta’s border. The fire from this sacrifice was then carried forth by a specially appointed fire-bearer or pyrphorus, all the way to the border.

The flame was never extinguished as the fire-bearer accompanied the army on its march, and he was followed by a flock of shepherded animals. Among these animals, the katoiades (probably the she-goat) was chosen as the prime sacrificial victim dedicated to the goddess Artemis Agrotera.

However, on the practical side of affairs, the flame was probably not snuffed out so that it could also serve as a cooking fire for the army on the march while maintaining its symbolic resplendence.

As for recreational activities, it was said the only time a Spartan warrior took a break from military training was during the war. However, the statement is not entirely true, since the Spartans were expected to exercise daily in both morning and evening sessions, even during ongoing campaigns. The only break they got from camp training was after dinner when soldiers huddled together to sing their hymns.

But even this ‘relaxing’ period was turned into a competition when every man was then called forth to sing a composition by Tyrtaios. Then the polemarchoi (a senior military title holder) decided on the winner and accorded him a choice piece of meat as a gift.

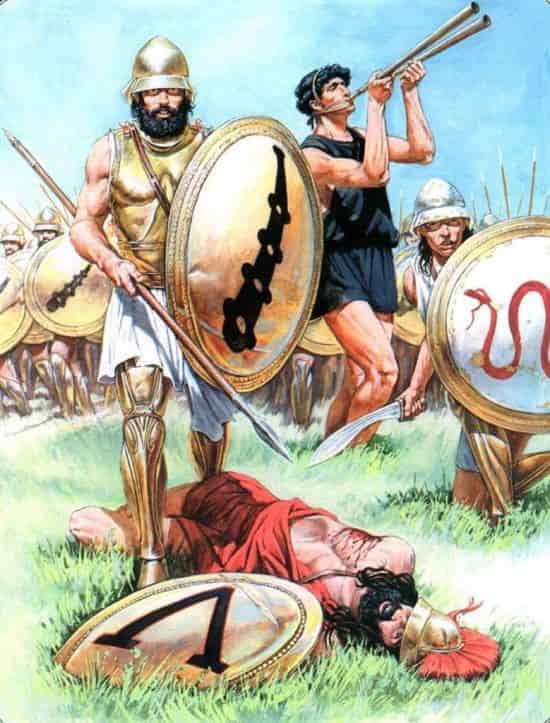

The singing, however, was not just limited to the camp. Before the commencement of a battle, the king once again made sacrifices to the goddess Artemis. The officers then grouped the hoplites and their lines started moving forward (with some wearing wreaths), while the king began to sing one of many marching songs composed by Tyrtaios. He was complemented by pipers who played the familiar tune, thus serving as a powerful auditory accompaniment to the progressing Spartan army.

Interestingly, as with many Greek customs, there might have been a practical side underneath this seemingly religious veneer. According to Thucydides, the songs and their tunes kept the marching line in order, which entailed a major battlefield tactic – since Greek warfare generally involved a steady approach to the enemy positions with a solid, unbroken line. This incredible auditory scope ended in a crescendo with the collective (yet sacred) war cry of paean, a military custom that was Dorian in origin.

The Chronic Shortage of ‘Spartans‘

Unfortunately for the Spartans, by the late 5th century, while their army boasted both courage and tenacity, their intrinsic strength was eroded by the available numbers. For example, at the Battle of Thermopylae (circa 480 BC), the Greek forces possibly had around 7,000 men that faced the army of Persian King Xerxes.

Within this force, the Spartiates (Spartan free citizens) themselves only had 300 men, while being accompanied by over a thousand perioikoi and helots from Sparta. Furthermore, Thucydides mentions how the low population of the Spartiates possibly allowed for a paltry force of only 2,560 Spartan hoplites by 418 BC.

The reasons for such low numbers could have been due to various possibilities, with hypotheses like how a calamitous earthquake afflicted the citizen Spartans circa 464 BC and the high casualties suffered in the Third Messenian War. To rectify the dwindling numbers, the Spartans began to actively recruit the free but non-citizen perioikoi class into its organizational scope.

By the time of the Second Peloponnesian War, the Spartans even trained hoplites from the helot ranks. The first of these helot hoplites were freed after they returned from their Thracian military campaign that took place over three years and ended in 421 BC. And meanwhile, the ‘home’ Spartan army was supplemented by neodamodeis (discussed earlier) – which comprised a separate batch of better-trained helot hoplites.

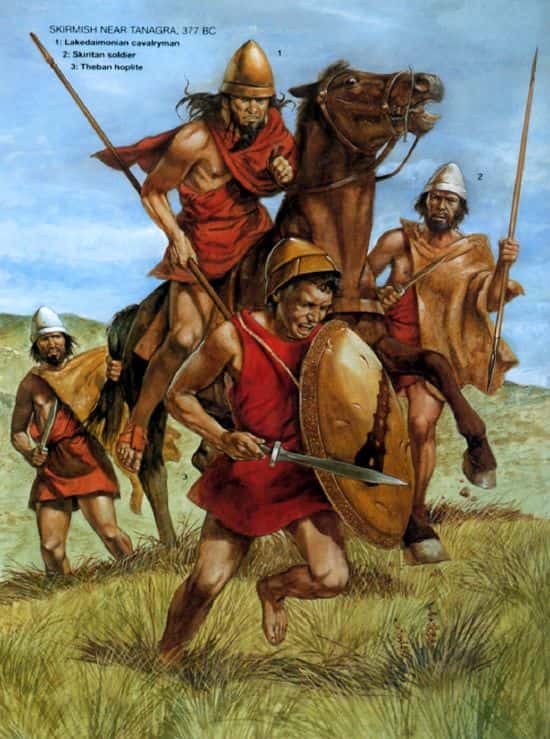

Unsung Cavalry, Archers, and Navy

After defeating the Spartan navy at the Battle of Pylos circa 425 BC, the Athenians controlled the Pylos peninsula (southwestern Greece) and established a raiding base in the region. The Spartans tried to counter the Athenian forays by establishing a cavalry force of 400 strength.

And while such a decision seemed tactically appropriate, the Spartan state was already financially debilitated by the Peloponnesian War. Consequently, it could ill afford a mounted force whose logistical scope and battlefield applications were (somewhat) alien to the Spartans.

As a solution, only the richest (from both full citizen Spartiate and perioikoi backgrounds) were allowed in the regiment since they could afford horses. Furthermore, according to the anecdotes of Plutarch, many of the recruits were possibly ill-suited to hoplite combat because of their physical incapability or low morale.

And given the Spartan penchant for close-quarters combat, it is not a big surprise that the art of archery also took a backseat when it came to their ‘conservative’ mode of warfare. But beyond just avoiding any archery training, the Spartans possibly abhorred archery as a skill.

Plutarch once again provides numerous anecdotes, and one of them relates to how a Spartan warrior was mortally wounded by an enemy archer. While lying on the ground, he was not worried about his death, but rather remorseful that he would die at the hands of a ‘womanish’ archer.

There were even incidences when the Spartans simply refused to fight when they were at the receiving end of a determined archery barrage. One such episode related to an encounter in 425 BC, when an entire Spartan garrison surrendered after being afflicted by enemy arrows. One of the survivors was later mocked by his Athenian counterpart, who derided the soldier for surrendering and thus not showcasing the braveness expected of a Spartan warrior.

The soldier replied that it was only a fine spindle (atrakon) that could distinguish the brave. The spindle, in this case, alluded to the instrument of a woman. Nevertheless, the austere Spartan troops were forced to adopt mixed tactics in the future that involved archers and other missile troops; but most of the archers were probably mercenaries employed from Crete. Additionally, the Spartans also began to employ the allied Skiritai, hailing from the mountainous Arcadia, as both hoplites and peltasts (skirmishers).

Similarly, confronted by Athenian naval supremacy at the early stages of the Peloponnesian War (431-406 BC), the Spartans employed and even revitalized their own fleet. This resulted in a short-lived naval dominance of the Aegean by Sparta, ironically (mostly) financed by the coffers of the Persian Empire. However, the tides soon turned against them by the late 4th century, when Sparta suffered decisive naval defeats at the hand of Athens – in the Battle of Cnidus (394 BC) and the Battle of Naxos (374 BC) respectively.

Culture of the Spartans –

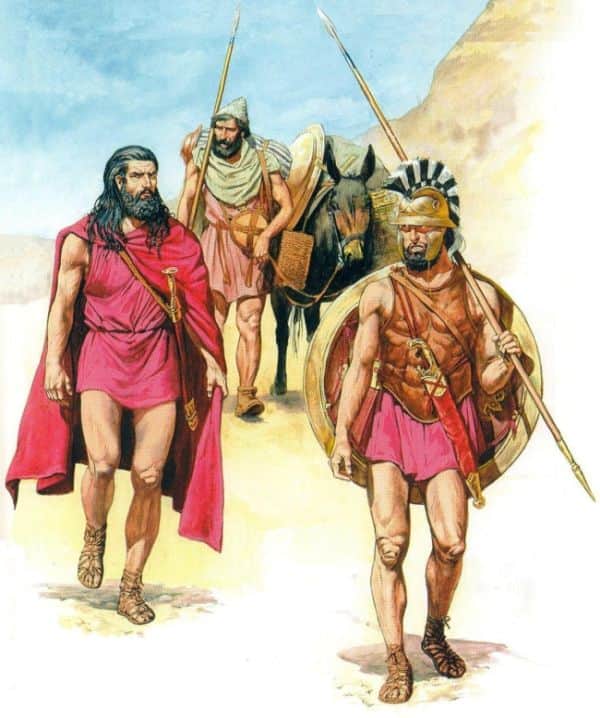

The Crimson Cloaks and Long Hair of Spartans

According to Xenophon, the crimson tunic and bronze shields carried by the Spartans were mandated by their legendary law-giver Lycurgus. Plutarch interestingly added to this view by stating that the red-hued clothing might have psychologically afflicted the enemy while also hiding the bloody wounds of a Spartan warrior.

The latter explanation might have some justification since most Greek armies contemporary to even Xenophon’s time adopted some variants of the crimson clothing, probably inspired by their Spartan counterparts.

On the other hand, beyond bravery and masculinity, there was possibly cultural reasoning behind the preference for crimson clothing in the Spartan army. To that end, crimson was generally considered an expensive dye. Xenophon also talked about how soldiers should be dressed at their best in a battle, in case the Gods granted them victory (and the troops, in turn, could mark the occasion in an opulent manner, or die in a regal manner).

So the Spartan mothers and wives proudly made the battle tunics of their sons and husbands with the finest possible materials. This societal tendency later transformed into a norm by the 4th century BC, and thus the Spartan hoplites became uniformly draped in crimson robes.

Earlier in the post, we also mentioned how the meirakion or youth was forced to cut his hair short while training in the agoge. But as Prof. Secunda noted, according to Xenophon, once the Spartan male entered manhood (possibly, at the age of 21), he was allowed (and sometimes even encouraged) to grow his hair long. This notion once again had a cultural bearing, with the elders believing that long hair made the person seem taller in stature, and thus more dignified as a Spartan warrior on the battlefield.

And according to Plutarch, long hair made good-looking men more handsome and ugly-looking men more terrifying – both of which had their psychological value in the Spartan army. And even beyond vanity, long hair has always been associated with freedom in Archaic Lakedaimonian circles – since many servile tasks couldn’t be achieved by keeping one’s hair long.

The Perception of Cowardice in Spartan Society

Given the propensity of Spartans for warfare and nigh ‘egotistic’ bravery, it doesn’t really come as a surprise that cowardice was not accepted as a general rule. Even simple accusations of cowardice against a Spartan warrior could initiate government rulings that officially excluded him from holding any office inside the state of Sparta. And if cowardice was ‘proven’, the person was simply banned from making any kind of legal contract and agreement, which also entailed marriage.

Furthermore, they were made to wear specially designed cloaks with multifarious colors and also had to shave half their beard. Such kinds of bitter episodes frequently led to suicides among the Spartan men who surrendered in battles (or ‘missed out’ on battles).

In fact, Herodotus’ account of the Battle of Thermopylae attests to a similar behavioral pattern when two men were publicly shamed for not being part of the ‘heroic’ conflict. Unable to bear the pressure, one of them hanged himself shortly afterward, while the other redeemed himself by getting killed in a later encounter.

Conclusion – The Rise and Decline of the Spartans

The Spartans were on the ascendancy in terms of power and prestige during the intermittent Greco-Persian Wars from circa 499-449 BC – as can be surmised from their leadership roles at the Battle of Thermopylae and Battle of Plataea. However, Sparta was soon embroiled in a far more attritional war with the emergent Athenians, resulting in the protracted Peloponnesian Wars from circa 431 to 404 BC.

Incredibly enough, the Spartans, known for their land-based armies, were successful in naval pursuits, thereby defeating the Athenian Empire and emerging as the most powerful Greek city-state in the late 5th century – early 4th century. The period, also known as the Spartan Hegemony, even entailed Spartan raids and forays into the Persian territories of Anatolia.

Unfortunately for the Spartans, their hegemonic tendencies drew the ire of the numerous Greek city-states who formed a coalition against Sparta. And while Sparta once again scored a string of land victories, their naval power was decimated, ironically by the combined efforts of both Athens and Persia (as discussed earlier, at the Battle of Cnidus, circa 394 BC).

Moreover, the state’s economic and social orders were crippled by the incessant warfare, low birth rate, and more importantly the revolts of the helots (who far outnumbered the Spartiates). And this long-term reversal of fortunes was rather exemplified by the disastrous defeat of a full land army of Spartans by the Theban general Epaminondas at the Battle of Leuctra, circa 371 BC.

In spite of being permanently ‘demoted’ from its hegemony after the defeat, the ever-persistent Spartans later fought the Macedonians and were forced to join the League of Corinth by Alexander. During the Punic Wars of the 3rd century BC, Sparta even remained an important ally of Rome.

But its political independence was snuffed out a century later when the Spartans were once again defeated by an alliance of Romans and the Achaean League circa 146 BC. Thereafter Sparta became a ‘free city’ under Roman influence, and as such, some Laws of Lycurgus were still followed inside the confines of the settlement.

One particular episode also epitomizes the relevance of Spartan military legacy in Roman circles – when Emperor Caracalla recruited 500 men (cohort) from Sparta who apparently fought as phalanx infantry circa 214 AD. However, even the nascent ‘existence’ of Sparta was finally extinguished when the city was sacked by the Visigoths circa 396 AD and its inhabitants sold into slavery.

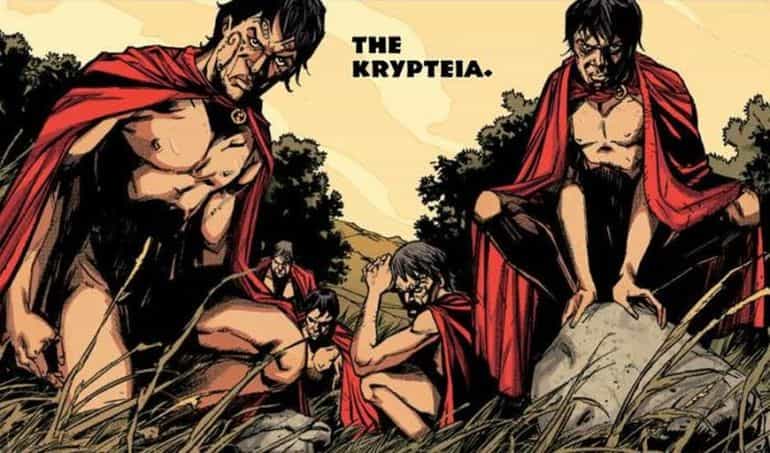

Honorable Mention – Krypteia

Despite our popular culture-inspired notions, the Spartan male was only considered a true soldier from the age of 18 (and not before that) when he was called the eiren or ‘adult citizen’. However, the Spartan secret service, known as krypteia, only inducted male members – who were generally above 27 years old (and below 30 years).

This ‘krypteia’ branch of the military practiced a cruel form of training for its initiates that required them to literally murder innocent helots. These helots belonged to the subjugated populace of Sparta which provided the free Lakedaimonians with slaves to work on fields, while the Spartans trained themselves for wars.

As for the barbarous process in question here, it started off when an ephor (an elected Spartan leader) upon entering his office, often declared war on the helots with the casus belli of fake revolts. This executive decision for all intents and purposes made the act of killing a helot legal from the perspective of the state’s judicial system.

And when the terrible order was passed, young Spartan men under the krypteia branch of ‘special services’ armed with just daggers and rations were let loose into the countryside populated by such slaves. These men used stealthy bandit-like tactics and ambushed unsuspecting helots to kill them mostly during times of the night.

The planning of such legalized murders was often elaborate and bloodthirsty. For example, there were cases when the strongest and largest helot was targeted first, so as to make a case for Spartan manliness in taking down bigger enemies.

*The article was updated on 4th June 2022.

Book References: The Spartan Army (By Nicholas Secunda) / Sparta (By H. Michell)/ Mortals and Immortals: Collected Essays (By Jean Pierre Vernant)

Online Sources: Ancient Military / The Parallel Lives by Plutarch / Instituta Laconica by Plutarch / BBC

Be the first to comment on "Spartans: The Mighty Warrior Society of Ancient Greece"