Introduction – The Greek Connection

Cleopatra – the very name brings forth reveries of beauty, sensuality, and extravagance, all set amidst the political furor of the ancient world. But does historicity really comply with these popular notions about the famous female Egyptian pharaoh, who had her roots in a Greek dynasty? Well, the answer to that is more complex, especially considering the various parameters of history, including cultural inclinations, political propaganda, and downright misinterpretations.

For example, some of our Hollywood-inspired popular notions tend to project Cleopatra as the quintessential Egyptian queen of ancient times. However, in terms of history, it is a well-known fact that Cleopatra or Cleopatra VII Philopator (Romanized: Kleopátrā Philopátōr)was of (mostly) Greek ethnicity. To that end, she was the last (active) ruler of the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty that held its major domains in Egypt.

In essence, as a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty, Cleopatra was a descendant of Ptolemy I Soter, a Macedonian Greek general, companion (hetairoi), and bodyguard of Alexander the Great, who took control of Egypt (after Alexander’s death), thereby founding the Ptolemaic Kingdom. On the other hand, the identity of Cleopatra’s grandmother is still unknown to historians.

Interestingly enough, while many of these Ptolemaic royal members preferred to exclusively reside in Alexandria, the Greek-origin city in northern coastal Egypt, they also tried to maintain displayable connections to native Egyptian customs, including the adoption of Pharaonic titles, syncretic gods, and even some indigenous forms of arts and architecture.

Contents

- Introduction – The Greek Connection

- The Early Tumultuous Years of Cleopatra

- The Political Tussle Between Sister and Brother

- The Bloody Episode of Pompey

- The ‘Caesarian’ Intervention

- The Affair and its Aftermath

- Cleopatra’s Tryst with Antony

- A Whirlwind of Romance and Propaganda

- The Fall of Antony and Cleopatra

- Drama and Death

- Reconstruction of Real Cleopatra

The Early Tumultuous Years of Cleopatra

Cleopatra (meaning – “glory of her father”) was born circa 69 BC to the ruling Ptolemaic pharaoh Ptolemy XII. Her mother’s identity is still vague in terms of historicity, with some hypotheses suggesting her name to be also Cleopatra – possibly Cleopatra VI Tryphaena (or Cleopatra V Tryphaena).

Now as for regional geopolitics, it should be noted that by this era, Egypt, while officially being a Ptolemaic domain, was already treated like a client state of Rome, especially because of the economic dependency (of the ruling class) and major financial players who had stakes in both the domains. Suffice it to say, the Romans, by virtue of their greater military power, were able to dictate policies and interventions in the political setup of the 1st century BC Ptolemaic Egypt.

To that end, by circa 58 BC, Cleopatra’s father Ptolemy XII was forced out of Egypt due to earlier disastrous economic policies, personal bankruptcy, and even covert secession of Egyptian territories to the Roman Republic. During his exile, he took his 11-year-old daughter Cleopatra and settled in the outskirts of Rome (and later in Ephesus), while the throne of Egypt was forcibly taken over by his elder daughter (i.e., Cleopatra’s older sister) – Berenice IV Epiphaneia.

Unfortunately for Berenice, her father had deeper connections to many wealthy Roman financiers. A group of such Roman influencers funded an unofficial military expedition under the leadership of Aulus Gabinius, the Roman governor of Syria. One Mark Antony (Marcus Antonius) also served in this force, and was said to have fallen in love with the 14-year-Cleopatra when the young teenager traveled with the Roman expedition. In any case, the campaign was successful and Ptolemy XII was reinstated on the Egyptian throne (while Berenice was possibly executed).

However, Ptolemy XII was still beholden to the Romans, in part due to his incurred debt. And so while the pharaoh ruled his remaining years with impunity, the shadow of the debt still lingered on the political front. Consequently, on Ptolemy XII’s death circa 51 BC, Cleopatra – who was designated as the co-ruler of Egypt (along with her younger brother – the 12-year-old Ptolemy XIII), ‘inherited’ the dues to Rome, which played a vital role in her relations, both political and personal, with the powerful Roman personalities.

The Political Tussle Between Sister and Brother

According to modern estimates, Cleopatra inherited a debt of a whopping 17.5 million drachmas from the Roman Republic. In spite of such enormous dues, her immediate concerns as the apparent ruler of Egypt pertained to the domestic front because of an unexpected famine brought on by the low levels of the Nile.

The precarious situation in Alexandria was even more exacerbated by the lawlessness of the unemployed Gabinius’ forces – the Gabiniani, mostly comprising mercenary Gallic and Germanic elements.

As for the political side of affairs, Cleopatra was known to have an independent nature, which rather reflected in her autonomous decision-making – that tended to eschew the counsel of the court members.

Such personal propensities and sovereign mode of ruling drew the ire of many high officials and nobles. Some of these powerful courtiers sided with the very young Ptolemy XIII and deposed Cleopatra from the throne, possibly as a means to directly influence the still teenage pharaoh.

To that end, by circa late 50 BC, Ptolemy XIII was probably the sole recognized ruler of Egypt – who had the upper hand in the power struggle between the siblings. And by 49 BC, Cleopatra had to flee to the Thebes region of Egypt, while by 48 BC, she was forced to travel to Syria to gather a force that could be used to invade her homeland. But even this force, en route to Alexandria, was stopped by the army of Ptolemy XIII.

The Bloody Episode of Pompey

But as with many momentous episodes of history, fate was on Cleopatra’s side, ushered by the civil war of Rome between Julius Caesar and Pompey. Interestingly enough, the Pompey family had closer connections with the Ptolemies of Egypt. And as such, even when Cleopatra was the official co-ruler, one of her signed decrees made the provision of 60 ships and 500 soldiers (including some of the infamous Gabiniani) for the Pompeiian forces – thus solving a fraction of the dues owed to Rome.

However, after a few years, in 48 BC (when the exiled Cleopatra was not part of the political setup at Alexandria), Pompey was decisively defeated by the forces of Julius Caesar at the Battle of Pharsalus in Greece.

Pompey managed to escape from the battlefield and sought refuge in Egypt because of his family’s close relationship with the Ptolemaic rulers. But the advisors of Ptolemy XIII, led by the military commander Theodotus, hatched a plan to double-cross Pompey, given the enhanced stature and political mileage of Caesar after his victory in Greece.

So in a bid to impress Caesar and also showcase their own power, the Ptolemaic advisors, with Ptolemy XIII’s permission, had Pompey stabbed to death after he reached the Egyptian shores. His severed head was then embalmed and sent to Caesar as an apparent gift of ‘friendship’. But Caesar was enraged by the seemingly cowardly act – and thus in a show of grief and magnanimity, marched on to Egypt to (allegedly) solve the political tussle between Ptolemy XIII and his older sister Cleopatra.

The ‘Caesarian’ Intervention

In reality, Julius Caesar arrived on the Egyptian shores with a few of his cohorts, took control of the royal palace, and declared martial law in Alexandria. Meanwhile, Ptolemy XIII, his advisors, and scattered forces had to flee to Pelusium to set up their court. It should be noted that during all this time, Cleopatra was also exiled – and this is where the resourceful nature of the queen of Egypt comes to light.

Comprehending the gravity of the situation and the presented opportunity, Cleopatra decided to meet Caesar personally and even persuade him to support her (after a slew of delegations). But time was of the essence, since Ptolemy XIII, emboldened by the native support, marched on to the outskirts of Alexandria to demand his city back from the encroaching Romans.

But it was Cleopatra who probably made the first personal contact with Caesar – either by dressing up attractively to entice the Roman general (according to Cassius Dio) or by hiding herself in a sack and crossing enemy lines (according to Plutarch).

Simply put, by virtue of the dangerous gamble, Cleopatra was able to successfully link up with Julius Caesar. However, after failing to stir up a rebellion in Alexandria, the impatient Ptolemy XIII was forced to besiege the palace in which both Caesar and Cleopatra were trapped (circa 47 BC). The pharaoh was supported by his advisors, remnants of the Egyptian army, and Gabiniani mercenaries (overall possibly totaling around 20,000 troops).

But while the siege was taking its course for six months, political machinations began to brew in the enemy camp, now with Arsinoe, Cleopatra’s half-sister, declaring herself as the new queen of Egypt (in Cleopatra’s place).

Ultimately, Roman reinforcements came just in time to defeat the besieging Ptolemaic forces. In the ensuing chaos, Ptolemy XIII fled the battle but was later drowned in the Nile, most of his advisors were either killed or executed, while Arsinoe was captured and exiled to the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus (although later she was killed by the soldiers of Antony at the behest of Cleopatra). More importantly, Cleopatra remained unharmed in all of this, and furthermore, she gained a powerful ally – Julius Caesar.

The Affair and its Aftermath

Suffice it to say, the 22-year-old Cleopatra was unequivocally declared as the ‘main’ ruler of Egypt. But once again following the ancient Egyptian tradition of sibling marriage (which many Ptolemaic members followed to showcase their affinity for the native culture), she was nominally married off to her 12-year-old brother Ptolemy XIV, who was designated as the co-ruler at least in theory.

However, by 47 BC, Caesar was already in a romantic affair with the sole queen of Egypt. And according to Suetonius – the pair flaunted their alliance and relationship by traveling across the Nile in a massive pleasure barge (although some scholars dismiss such accounts as just sensationalism on the part of the Romans).

Quite intriguingly, Cleopatra even gave birth to their son Ptolemy Caesar, also known as Caesarion, in 47 BC and had him proclaimed as her heir to the throne of Egypt (although Caesar didn’t make any official commitment to this claim).

By 46 BC, Caesar had to return to Rome, and he was openly accompanied by Cleopatra and her entourage – who were allowed to live within the Horti Caesaris (‘Gardens of Caesar’), the estate of Julius Caesar. During this time, Cleopatra was officially designated as socius et amicus populi Romani – ‘friend and ally of Rome’, thereby granting her the status of a client ruler. Cleopatra supposedly reciprocated by endowing lavish gifts and meeting Roman dignitaries (including Cicero) from across the Tiber.

Unfortunately, for the couple, not all were impressed by the ostentatious show of political and regal power. Furthermore, Julius Caesar was still married to Calpurnia, and Roman laws prohibited bigamy from a legal standpoint. As the clearly unsympathetic Cicero said circa 45 BC –

I detest the Queen. For all the presents she promised were things of a learned kind, and consistent with my character, such as I could proclaim on the housetops…and the insolence of the Queen herself when she was living in Caesar’s trans-Tiberine villa, the recollection of it is painful to me.

But beyond opulence, it was the dictatorial nature of Caesar that caused his demise – and thus he was brutally assassinated on the famous Ides of March, circa 44 BC. Incredibly enough, the guileful Cleopatra stayed in Rome for a month even after her lover’s murder, possibly in a bid to have her son, the infant Caesarion, recognized as the heir to Caesar.

But Caesar had already named his nephew Octavian as his heir and prime beneficiary – a decision that was to sow discord among the various groups of Caesar’s supporters in the near future.

Cleopatra’s Tryst with Antony

The rather ruthless nature of Cleopatra comes to light when she had her younger brother (and official co-ruler) Ptolemy XIV killed by poisoning in the very same year of Caesar’s assassination. Later on, she actively supported the Second Triumvirate of Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus, against the assassins of Caesar – by sending both troops (who were captured by Cassius, one of Caesar’s assassins) and ships.

By late 42 BC, the assassins were defeated, and by early 41 BC, Antony effectively gained control of the eastern half of the Roman Republic, while Octavian controlled the western half.

And it was after Antony established his stronghold at Tarsos in Anatolia that a summons was made to Cleopatra to attend his court. According to some scholars, Antony wanted to conduct both a romantic and political liaison with the sole Egyptian ruler.

In any case, after some rebuffs, Cleopatra made her way to Tarsos, cleared her name in support of Caesar and Antony (since previously some of her troops were captured by the assassins), and possibly even hosted lavish banquets atop barges for Antony and his senior officers.

Thus once again, an alliance was forged between a powerful Roman military commander and a charming Egyptian queen – sprinkled with both romance and sensuality. According to Plutarch –

She came sailing up the river Cydnus in a barge with a gilded stern and outspread sails of purple, while oars of silver beat time to the music of flutes and fifes and harps. She herself lay all along, under a canopy of cloth of gold, dressed as Venus in a picture, and beautiful young boys, like painted Cupids, stood on each side to fan her. Her maids were dressed like Sea Nymphs and Graces, some steering at the rudder, some working at the ropes…

A Whirlwind of Romance and Propaganda

By late 41 BC, it was Antony’s turn to visit Egypt at the behest of his lover Cleopatra, and he was received with pomp and celebration in Alexandria, given his earlier role in aiding Ptolemaic monarchs like Ptolemy XII (Cleopatra’s father).

This was certainly in contrast to Julius Caesar’s arrival at the city with his soldiers and martial rule. And by the late 40 BC, Cleopatra even gave birth to twins – a son named Alexander Helios and a girl named Cleopatra Selene II, both of whom were acknowledged by Antony as his own children.

It should be noted that from the legal standpoint, Antony was already married to Fulvia and later to Octavia (Octavian’s sister). But over the course of the decade circa 41 – 31 BC, the relationship between Antony and his one-time ally Octavian worsened significantly due to the political fallout over the control of the Roman Republic.

In essence, Octavian continued to advertise his status as the ‘true’ heir of Caesar in Rome, while Antony, often strongly aided and sometimes latently pressured by Cleopatra, began to flaunt his ties with the Greek East of the Roman Republic.

The latter scope was further ‘stretched’ by Antony when he even granted various Roman territories in the Levant, Libya, and Crete to the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Cleopatra. Unfortunately, for Antony, in contrast to such seemingly haughty decisions, his political mileage in Rome took a hit after he led a disastrous military campaign to Parthia (that was not fully aided by Octavian).

And the already deteriorating relations between him and Octavian suffered the proverbial ‘last nail’ when Antony officially divorced Octavia in 33 BC, in a bid to marry Cleopatra.

By 34 BC, the propaganda wars had already started between Octavian and Antony. And quite ironically, these sets of disinformation and publicity spread by the former influenced the portrayal of Cleopatra in Augustan-era literature and are carried over by her depictions in our modern popular culture.

In that regard, many of her Roman opponents portrayed her as the wily seductress who persuaded Antony to betray his homeland. Some even accused Cleopatra of witchcraft and sorcery that were used to ‘brainwash’ Antony. In a speech as a consul, Octavian himself publicly accused Antony of being a slave to his Oriental queen.

The Fall of Antony and Cleopatra

By 32 BC, many senators and officials in support of Antony had to flee from Rome, threatened by Octavian’s private army. And finally, Octavian scored his casus belli (the justification for war) by getting hold of Antony’s will that was forcefully seized from the Temple of Vesta (by agents of Octavius) and then read in the Senate.

The contents possibly revealed how Antonius had plans to divide up the Roman territories in the east among his own sons. But the most contentious point in the will relates to how Antony put forth Caesarion – the alleged son of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra, as the heir to Caesar, thereby sidelining Octavian, who was widely perceived as the true (yet adopted) heir of Caesar.

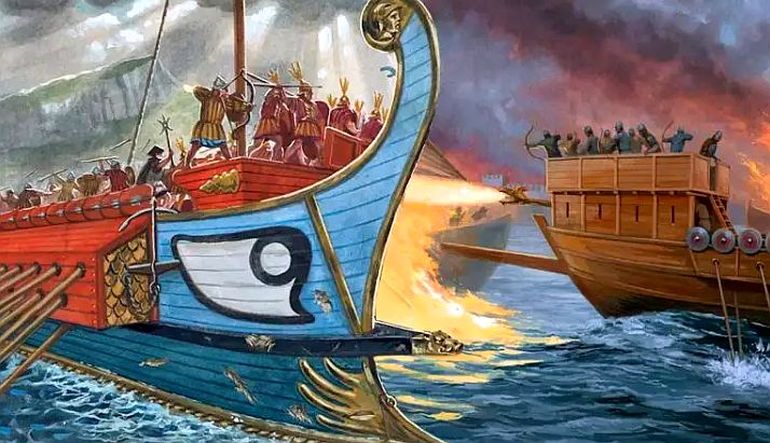

Consequently, circa 32 BC, the Senate officially revoked the consulship of Antony and declared war on Cleopatra’s regime in Egypt. This inevitably resulted in the showdown between the two powerful rivals – Octavian and Antony, culminating in the naval Battle of Actium (31 BC).

And while the combined fleet of Antony and Cleopatra was probably pretty large, Octavian’s fleet was more maneuverable and composed of professional forces (commanded by the experienced Agrippa). Consequently, the momentous engagement resulted in a decisive victory for Octavian – forcing both Antony and Cleopatra to flee to Egypt via Greece.

Drama and Death

Interestingly enough, while not often mentioned in popular history, it is entirely possible that after the Battle of Actium, there was a rift between the two lovers. Cleopatra, on her part, may have viewed Antony as a liability due to the deterioration of his political power, while Antony might have perceived Cleopatra as a self-centered ally who was mostly concerned with preserving the throne of Egypt for her son Caesarion.

But the two did manage to show a united front when it came to dealing with the overtures of Octavian, in spite of the latter only being willing to negotiate with Cleopatra (since she still had her political claim over Egypt). However, the lengthy negotiations failed, and thus Octavian’s forces marched on to Egypt from two sides – the Levant and Cyrene (Libya).

The invasion was successful and Antony, despite taking an active part in dogged defensive maneuvers in the neighborhoods of Alexandria, grew despondent with his precarious position. In a bitter turn of events, the Roman general committed suicide at the age of 53 (possibly by stabbing himself in the stomach), upon hearing false news of Cleopatra’s death – which was probably propagated by Cleopatra herself.

As for Cleopatra, she was only bearably open to an agreement with Octavian, although her life was spared. But the mediation was derailed when Octavian unceremoniously seized three of her children. According to Livy, Cleopatra, on personally meeting with Octavian, exclaimed – οὑ θριαμβεύσομαι (‘I will not be led in a triumph’).

Unfortunately, a spy report received by her only three days later revealed how Octavian had made plans to deport her to Rome, presumably to be paraded in the victory march. On hearing the report, the proud Cleopatra also committed suicide at the age of 39, circa 30 BC.

But even the suicide of Cleopatra is steeped in drama and mystery, with popular portrayal showcasing how she allowed herself to be bitten by an asp (venomous Egyptian snake) or an Egyptian cobra. This representation is based on Plutarch’s account, who also went on to say how the poison was later introduced through a knêstis (‘grater’) that made scratch marks on her arm.

However, according to Cassius Dio, she injected herself with the poison, while Strabo claimed she used an ointment. Moreover, many ancient accounts mention how no snakebite marks were found on the body, but puncture wounds were visible on Cleopatra’s arms.

Reconstruction of Real Cleopatra

From the historical perspective, one thing is for certain – the femme fatale aura of Cleopatra had more to do with her incredible influence on two of the most powerful men during the contemporary era, Julius Caesar and Mark Antony (Marcus Antonius), as opposed to her actual physical beauty.

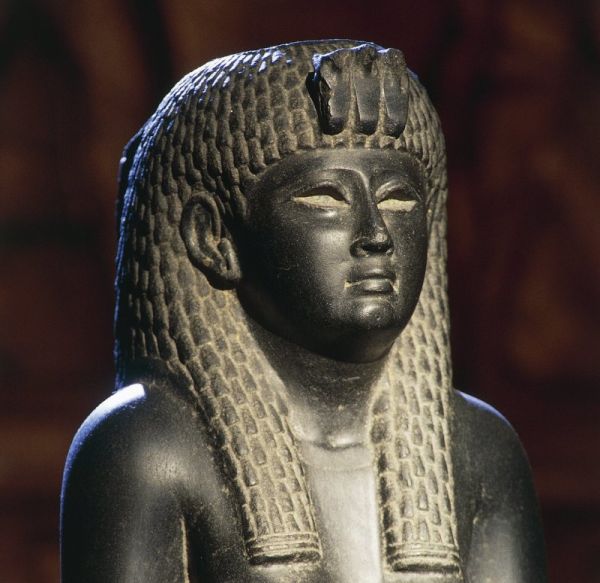

Taking all these factors into account, reconstruction specialist/artist M.A. Ludwig has made recreations of the renowned visage of Cleopatra VII Philopator, the last active pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt. Now if you look at the videos, we can see that these reconstructions are based on an actual bust (except the last video).

This sculpture in question here is thought to be of Cleopatra VII and is currently displayed at the Altes Museum in Berlin. And please note that the following recreations are just ‘educated’ hypotheses at the end of the day (like most historical reconstructions), with no definite evidence that establishes their complete accuracy when it comes to actual historicity.

And while the animation will undoubtedly confuse many a reader and history enthusiast, actual written records of Cleopatra vary in their tone from a profusion of appreciation (like Cassius Dio’s account) to practical assessments (like Plutarch’s account).

Pertaining to the latter, Plutarch wrote a century before Dio and thus should be considered more credible with his documentation being closer to the actual life period of Cleopatra. This is what the ancient biographer had to say about the female pharaoh – “Her beauty was in itself not altogether incomparable, nor such as to strike those who saw her.”

Even beyond ancient accounts, there are extant pieces of evidence of Cleopatra’s portraiture to consider. To that end, around ten ancient coinage specimens showcase the female pharaoh in a rather modest light. Oscillating between what can be considered ‘average’ looking to representing downright masculine features with the hooked nose, Cleopatra’s renowned comeliness seems to be oddly missing from these portraits.

Now since we are talking about history, some of the masculine-looking depictions were possibly part of political machinations that intentionally equated Cleopatra’s power to her male Ptolemaic ancestors, thus legitimizing her rule.

Conclusion – Character Profile of Cleopatra

Ambitious, ruthless yet resourceful, and magnetic – this, in a nutshell, defines Cleopatra and her aspirations for the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt. Pertaining to the former, we have already discussed her fascinating political journey and acumen that sometimes bordered on the guileful. As for the latter qualities, while she was born as a privileged member of the Greek elite in Alexandria, Cleopatra did make considerable efforts to not only rule but also govern and enhance the status of Egypt in the ancient world.

To that end, unlike many other Hellenistic Greek rulers, Cleopatra took a keen interest in learning the native Egyptian language (which possibly made her the first Ptolemaic ruler to know Egyptian). Additionally, she was a known polyglot by the age of 18, having some level of speaking skills in Ethiopian, Aramaic, Syriac, Latin, Median, and Parthian. This was complemented by her knowledge of the Greek arts of oration and philosophy.

Furthermore, many of the ancient writers genuinely admired (or grudgingly hailed) her wit, intelligence, and ‘irresistible charm’ (as mentioned by Plutarch) – qualities that were instrumental in convincing and influencing two of the most powerful men of the era, who were womanizers by their own right. To that end, Professor Kevin Butcher from the University of Warwick, who is an expert on Greek and Roman coinage, wrote (in History Extra) –

The modern negative reaction to the face of Cleopatra tells us more about our love of stories than anything about this most famous of Egyptian queens, who ruled from 51 to 30 BC. For us, the reality of her coin portraits clashes with the much greater myth of Cleopatra, a myth so grand that it has practically consumed the person behind it.

Other Online Sources: Britannica / Biography.com

*The article was updated on 24th July 2023.

Be the first to comment on "The Real Cleopatra: Remarkable History and Reconstruction of the Ancient Queen"