Introduction

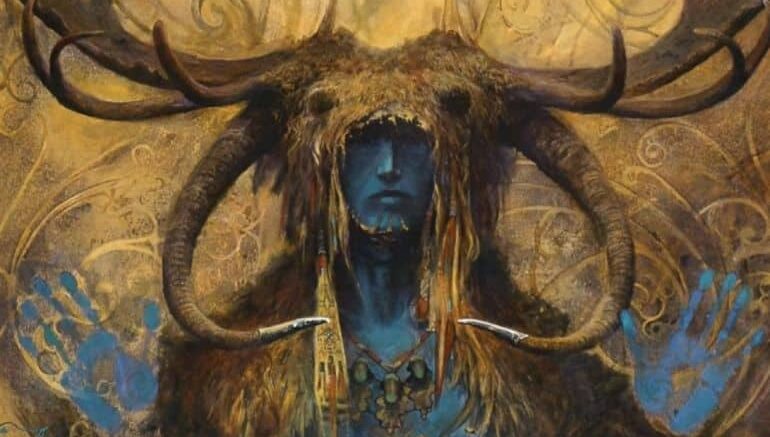

Arguably the most visually impressive and rather portentous of ancient Celtic gods, the name Cernunnos is actually the general term (theonym) given to the deity ‘Horned One’. As the horned god of Celtic polytheism, Cernunnos is often associated with animals, forests, fertility, and even wealth. His very depiction mirrors such attributes, with the conspicuous antlers of the stag on his head and the poetic epithets like ‘Lord of the Wild Things’.

Contents

Origins and History of Cernunnos

As we mentioned before, Cernunnos is often identified with the horned deity of Celtic mythology and folklore. Interestingly enough, the very theonym ‘Cernunnos’ is rather a general or conventional one often used in Celtic studies. As such the term is found only once in the historical context – mentioned in the Pillar of the Boatmen, a Roman column dating from circa 1st century AD, possibly erected by a guild of Celtic sailors.

To that end, this column, dedicated to Emperor Tiberius, has inscriptions in Latin but with features of Gaulish language that go on to depict a ‘mix’ of Celtic deities and Roman mythical figures as bas-reliefs (Cernunnos pictured above).

However, quite intriguingly, the visual representations of the horned deity (as one of the Celtic gods) predate such inscriptions and names by centuries, including small figurines dating from circa 7th-4th century BC and Ist century BC, from different parts of western Europe.

Some have even conjectured how the horned deity was venerated as the shamanic god of the hunt since prehistoric times. In essence, while we prescribe the theonym ‘Cernunnos’ to the Horned God of the Celts, the deity in itself is far older than the conventional name.

As for the mythological side of affairs, given the Roman penchant for identifying foreign deities with their own (known as interpretatio Romana), Cernunnos was likened to Dis Pater, along with Mars and Mercury. That was because, according to the Romans, most of these entities were regarded as the rulers of the treasures of the underworld (possibly signifying mineral wealth).

As for the Irish side of affairs, Cernunnos is also vaguely identified with Conall Cernach, the foster brother to the hero Cú Chulainn – with the Cernach epithet (sounding close to Cernunnos) alluding to ‘being victorious’ or ‘bearing a prominent growth’.

Talking of etymology, befitting the mysterious nature of the forest god, his theonym ‘Cernunnos’ also has ambiguous origins. However, the similar-sounding karnon from Gaulish (cognate with Latin cornu and Germanic hurnaz), ultimately derived from Proto-Indo-European k̑r̥no-, means ‘horn’. In that regard, 12th-century Eastern Roman scholar and archbishop Eustathius of Thessalonica referred to the animal-shaped Celtic military horn as the carnyx.

Depictions of Cernunnos

As we mentioned in the earlier entry, there are representations of the Celtic Horned God that predate the Cernunnos on the Pillar of the Boatmen (where he is also depicted as a horned figure). Apt examples would pertain to an antlered human figure featured in a 7th-4th century BC dated petroglyph in Cisalpine Gaul and other related horned figures (included a deity with two faces) worshipped by the Celtiberians based in what is now modern-day Spain and Portugal.

And the most well-known depiction of the deity (pictured above) can be found on the Gundestrup Cauldron (circa 1st century BC), discovered from Jutland – comprising portions of present-day Denmark and Germany.

Interestingly enough, back in 2018, archaeologists discovered a 5 cm long copper alloy human figurine (pictured above), probably dating from the 2nd century AD, at the Wimpole Estate in Cambridgeshire, England. And while the statuette, holding a torc (high-value Celtic neck ring) is seemingly ‘faceless’, researchers have hypothesized that it represents Cernunnos. As Shannon Hogan, National Trust Archaeologist for the East of England said –

This is an incredibly exciting discovery, which to me represents more than just the deity, Cernunnos. It almost seems like the enigmatic ‘face’ of the people living in the landscape some 2,000 years ago. The artifact is Roman in origin but symbolizes a Celtic deity and therefore exemplifies the continuation of indigenous religious and cultural symbolism in Romanised societies.

Most of these figurines and inscriptions represent a human or a half-human (or humanoid figure) with antler crowns. Such historical portrayals, in turn, influence the modern representations of Cernunnos as the forest deity with his set of elaborate horns (discussed later in the article).

Myths of Cernunnos

Given the ambiguous scope of the Horned God in Celtic mythology, there are no recorded myths and ancient literary sources that directly pertain to the figure of Cernunnos. However, the imagery of horns and serpents do play their part in some mythical narratives of ancient Europe. For example, in the 8th-century Irish tale Táin Bó Fraích, the warrior-hero Conall Cernach bypasses a fort to confront a mighty serpent that is guarding the stronghold’s treasure.

But instead of a valiant clash, the story turns anti-climatic – with the serpent surrendering itself by girdling itself along the hero’s waist. And as we mentioned before, the Cernach epithet could alternatively mean ‘angular, having corners’ or ‘bearing a prominent growth’, thus possibly referring to horn-like receptacles.

Now, in an intriguing manner, depictions of snakes and even ram-horned snakes were found in northern-eastern Gaul – the very same area known for its association with the ancient cult of Cernunnos (or the Horned God).

Other similar depictions are also found outside of the area, including the famous Gundestrup Cauldron from Jutland. However, it should be noted that such depictions are not unique in their connection to Cernunnos, but were rather found in conjunction with other Romano-Celtic deities, like the Celtic (syncretic) versions of Mars and Mercury.

Attributes of Cernunnos

As the Horned God of Celtic polytheism, Cernunnos is often associated with the deity of animals, fertility, life, and even wealth (in his syncretic Romano-Celtic form, as we discussed earlier). Pertaining to animals and wildlife, Cernunnos has been offered poetic epithets like ‘Lord of Wild Things’ by many modern pagan movements. And from the historical perspective, the Horned God (or similar deities) was symbolically represented by the stag, along with a flurry of other critters, ranging from bulls, and boars to rats and dogs.

Relating to this association with animals and hunting, some have also conjectured how Cernunnos could be a god of the underworld (since hunting results in death). But once again, from the historical angle, there is no evidence to back up such a claim.

As for his attribute of a life-endowing force, the scope might be related to the seasonal changes and their effects on forests and vegetation, with the spring and summer bringing forth the verdancy, regeneration, and lushness of the many trees and plants.

Modern Revival of Cernunnos

The popular imagery of Cernunnos as the otherworldly horned figure residing within the depth of forests is arguably inspired by Margaret Murray’s 1931 book, the God of the Witches. Murray, who was a historian, anthropologist, and folklorist (famous for her Witch-Cult theory), surmised that Herne the Hunter, a post-Christianity deity from around the Berkshire region, was a localized version or aspect of Cernunnos. Interestingly enough, Herne was also mentioned by Shakespeare in The Merry Wives of Windsor –

There is an old tale goes that Herne the Hunter,

Some time a keeper here in Windsor Forest,

Doth all the winter-time, at still midnight,

Walk round about an oak, with great ragg’d horns;

In any case, modern versions of Cernunnos are also prevalent in some traditions of Wicca (known as Kernunno in the Gardnerian Wicca), with the Horned God often regarded as a deity of fertility and renewal.

To that end, Cernunnos is perceived in his death aspect at the onset of winter – who is once again resurrected to impregnate the earth goddess, thereby resulting in cyclic regeneration of life by the springtime. Now, of course, it should be noted that such associations are a result of the culmination and combination of various horned entities that were venerated in ancient Europe and even other parts of the world.

Other Online Sources: Britannica / ManyGods.org / Mythopedia

Book References: Pagan Celtic Britain: Studies in Iconography and Tradition (By Anne Ross) / God of the Witches (By Margaret Murray)

Be the first to comment on "Cernunnos: The Mysterious Celtic Horned God of the Forests"