Introduction

Previously, we had talked about the oldest known song in the world, better known as the Hurrian Song to Nikkal, which was originally composed in the northern Syrian settlement of Ugarit almost 3,400 years ago. However, arguably the most renowned of Mesopotamian cultural achievements relates to the Epic of Gilgamesh – possibly the oldest known epic in the world and also the earliest surviving great work of literature.

Quite intriguingly, the literary history of the titular character Gilgamesh comes down to us from five Sumerian poems, though the first iterations of the epic itself were possibly compiled in ‘Old Babylonian’ versions (circa 18th century BC).

Contents

The Origins – Bilgames, The Sumerian Legacy

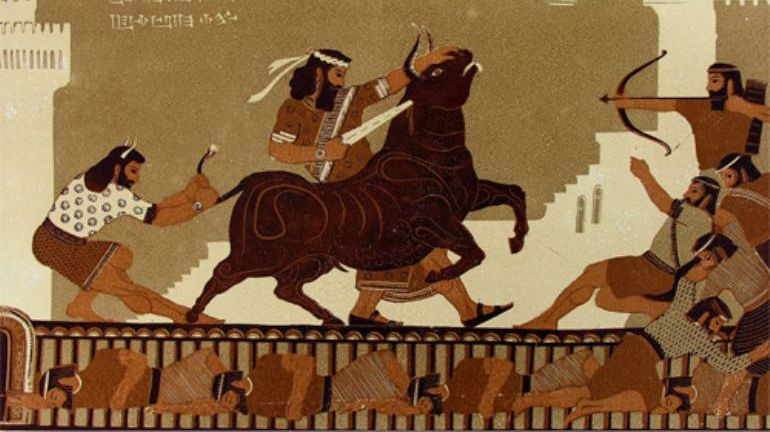

Befitting the literary value of the Epic of Gilgamesh, the multilayered history of the character of Gilgamesh himself is fascinatingly derived from five Sumerian poems (dating from circa 3rd millennium BC) that portray a King of Uruk named ‘Bilgames’.

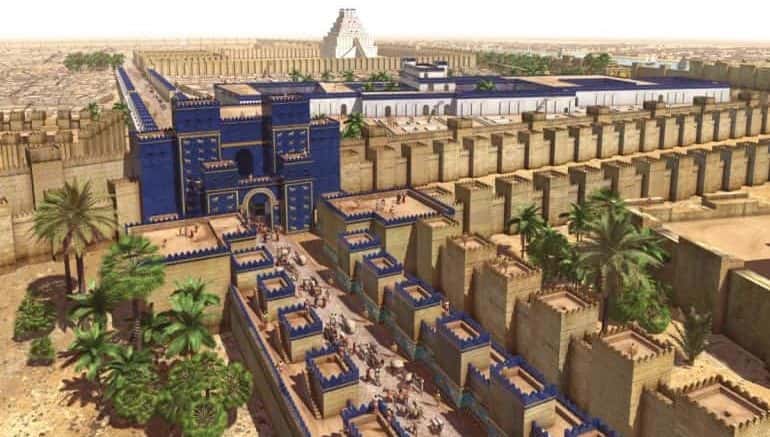

To that end, historians are aware of the existence of a few such independent stories of Gilgamesh (or his Sumerian counterpart) that were composed before the epic itself. Some of these pieces of ‘pre-epic’ evidence are also derived from the 3rd millennium BC inscriptions that credit Gilgamesh with the building of the great walls of Uruk, corresponding to present-day Warka in Iraq.

This historical narrative naturally brings up the question – so when was the Epic of Gilgamesh written? Well, for starters, rather than being ‘written’ as a separate work of literature, the first surviving version of this epic was actually compiled from the aforementioned different tales.

Better known as the Old Babylonian version, dating from circa 18th century BC, the compilation is also titled after its incipit, Shūtur eli sharrī (“Surpassing All Other Kings”). However, the ‘best’ known version of the Epic of Gilgamesh comes from a later Babylonian compilation dated from circa the 13th to the 10th centuries BC and is titled Sha naqba īmuru (“He Who Saw the Deep”).

So is the Epic Sumerian or Babylonian?

So, once again another query can be put forth – is the Epic of Gilgamesh Sumerian or Babylonian? Now as we mentioned before, the origins of Gilgamesh undoubtedly lie in the ancient Sumerian language.

However, on the other hand, the epic with its controlled narrative – as we know it today (and even during the late Babylonian period), comes exclusively from the works of Babylonian writer Shin-Leqi-Unninni (circa 1300-1000 BC) who not only translated and edited the original story (or compilation) but also made his own modifications to the Sha naqba īmuru – the ‘standard’ version of the epic.

Simply put, while the provenance of these literary works is based on Sumerian language and literature, the end product/s (as available to the common people of the era after the 2nd millennium BC) of the epic was probably composed in Babylonian and related Akkadian – languages that were theoretically different from Sumerian, based on their Semitic origins. As the Sumerian scholar Samuel Noah Kramer made it clear (in his book History Begins at Sumer) –

Of the various episodes comprising The Epic of Gilgamesh, several go back to Sumerian prototypes actually involving the hero Gilgamesh. Even in those episodes which lack Sumerian counterparts, most of the individual motifs reflect Sumerian mythic and epic sources. In no case, however, did the Babylonian poets slavishly copy the Sumerian material.

They so modified its content and molded its form, in accordance with their own temper and heritage, that only the bare nucleus of the Sumerian original remains recognizable. As for the plot structure of the epic as a whole – the forceful and fateful episodic drama of the restless, adventurous hero and his inevitable disillusionment – it is definitely a Babylonian, rather than a Sumerian, development, and achievement.

Animation of the Epic of Gilgamesh

The good news for history (and mythos) enthusiasts is that back in 2008, Sean Goodison created an animated comic for his final year project while studying computer graphic design. This niftily created animated short encompasses the core story of the Epic of Gilgamesh in all its ten minutes of glory.

Epic of Gilgamesh – Sung in Sumerian

And since we talked about the origins of the epic, a few ancient Mesopotamian bards and scholars might have still sung some of Gilgamesh’s heroic exploits in Sumerian. To that end, Canadian musician Peter Pringle presented his version of the Epic of Gilgamesh in ancient Sumerian, with the video covering the opening lines of the epic poem. According to the musician –

What you hear in this video are a few of the opening lines of part of the epic poem, accompanied only by a long-neck, three-string, Sumerian lute known as a “gish-gu-di”. The instrument is tuned to G – G – D, and although it is similar to other long neck lutes still in use today (the tar, the setar, the saz, etc.), the modern instruments are low tension and strung with fine steel wire.

The ancient long neck lutes (such as the Egyptian “nefer“) were strung with the gut and behaved slightly differently. The short-neck lute known as the “oud” is strung with gut/nylon, and its sound has much in common with the ancient long-neck lute although the oud is not a fretted instrument and its strings are much shorter (about 25 inches or 63 cm) as compared to 32 inches (82 cm) on a long-neck instrument.

Epic of Gilgamesh – Read in Akkadian

The audio clip (above) presents a segment of The Epic of Gilgamesh found in a part of Tablet II. This Old Babylonian (a dialect of Akkadian) version was read by Antoine Cavigneaux.

And in case one is interested in an English transcription accompanying a passage (read in Akkadian) from the Epic of Gilgamesh, you can also take a gander at the YouTube video below, courtesy of Harith Sahib –

The Relation between Akkadian and Sumerian

Finally, it should be noted that ancient Sumerian as a language almost died out by the 20th century BC, and was only used in a limited official capacity by scholars (much like Latin and Sanskrit in our modern times) when the first instances of the Epic of Gilgamesh were as compiled.

However, at the same time, it heavily influenced ancient Akkadian (of which Babylonian was a variant), the lingua franca of much of the Ancient Near East. And beyond just cultural affiliations with the advanced Sumerians, the Akkadians also adopted (and loaned) many of the military systems and doctrines of their Mesopotamian brethren.

In any case, this scope of common influence and lexical borrowings were so heavily pronounced that many scholars consider both languages to have linguistically converged, known as sprachbund or “federation of languages”. So in essence, the Epic of Gilgamesh alludes to a cultural synthesis, evolution, and identity of the thriving ancient Mesopotamian society.

To that end, the literary influence of this epic work went beyond the linguistic limits to aptly account for Mesopotamian progression in terms of art, architecture, culture, and even rising urbanism. Pertaining to the latter, the first known description of urban planning was also found in the Epic of Gilgamesh –

Go up on to the wall of Uruk and walk around. Inspect the foundation platform and scrutinize the brickwork. Testify that its bricks are baked bricks, And that the Seven Counsellors must have laid its foundations. One square mile is city, one square mile is orchards, one square mile is claypits, as well as the open ground of Ishtar’s temple.Three square miles and the open ground comprise Uruk. Look for the copper tablet-box, Undo its bronze lock, Open the door to its secret, Lift out the lapis lazuli tablet and read.

And finally, there is a veritable collection of Old Babylonian recordings that can be found at this SOAS University of London online archive.

Featured Image: Illustration by Wael Tarabieh. Credit: Saatchi Art

Be the first to comment on "The Epic of Gilgamesh Presented Through Animation and Songs"