Introduction

This is how historian Stephen Bertman partly summarizes the character of Hammurabi, the sixth king of the Amorite dynasty, who ascended the Babylonian throne in 1792 BC –

Hammurabi was an able administrator, an adroit diplomat, and a canny imperialist, patient in the achievement of his goals. Upon taking the throne, he issued a proclamation forgiving people’s debts and during the first five years of his reign further enhanced his popularity by piously renovating the sanctuaries of the gods, especially Marduk, Babylon’s patron. Then, with his power at home secure and his military forces primed, he began a five-year series of campaigns against rival states to the south and east, expanding his territory.

Suffice it to say, the great Hammurabi espoused the mentality of a keen ruler who gave equal importance to the opportunities of populist civic projects and military conquests. However, beyond just contemporary affairs, the name Hammurabi in our modern times mostly pertains to that of an ancient law-giver – courtesy of a massive code of laws that dictated various facets ranging from labor contracts, and properties to even household and family relationships.

So, without further ado, let us check out ten things you should know about the Code of Hammurabi that might drive away some of the historical misconceptions that have accumulated over the years.

Contents

- Introduction

- A Code Found Across Numerous Objects, Not A Single Specimen

- Code of Hammurabi Is Not The Oldest Set of Laws

- An Enlightening Start To The Code of Hammurabi

- Some Laws Are Quite Harsh and Even Bizarre

- Laws Were Different For the Different Social Classes And the Genders

- Some Laws Were Also Quite Progressive

- The Institutionalization of Slavery

- Presumption of Innocence Taken To An Extreme Level

- Hammurabi Was Known More As A Builder And A Conqueror Than A Law-Giver

- The Code of Hammurabi Was Not Even Found in Babylonia

A Code Found Across Numerous Objects, Not A Single Specimen

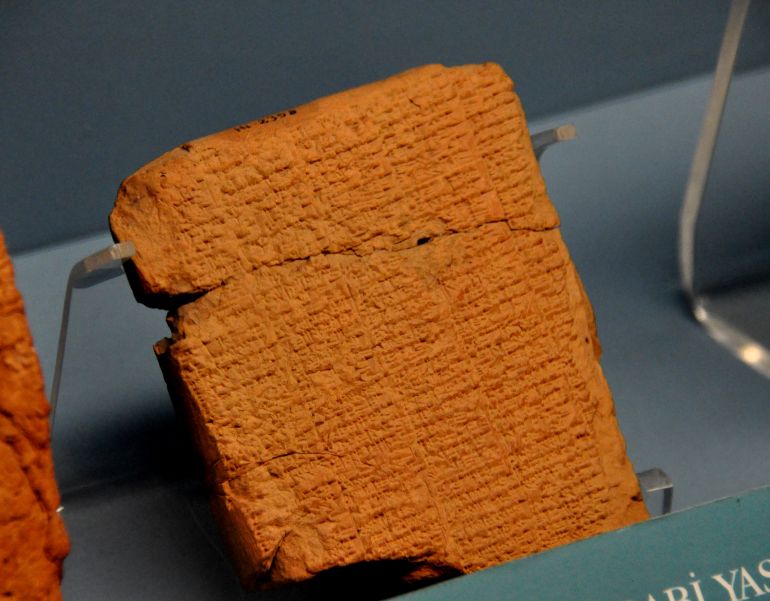

The almost complete version of the Code of Hammurabi with its 282 laws, was carved into a diorite stele (see above picture) which is sort of shaped like a huge index finger. Inscribed in the Akkadian language, the humongous 2.25-m (7.4 ft) tall stele (currently showcased at the Louvre museum) displays a cuneiform script carved into its side. However, contrary to popular notion, the Code is not only found on this massive ancient specimen.

Quite intriguingly, there are other copies of various portions of this Code that might even predate the stele itself – with most pertaining to clay tablets. In fact, one such clay tablet is displayed in the Louvre, and it has the Prologue of the Code of Hammurabi consisting of the first 305 inscribed squares (on the stele). Other clay tablets have also been found that match or at least parallel the inscriptions found on the stele, like the fragmentary Akkadian cuneiform tablet that was discovered at Tel Hazor, Israel dated from around 1700 BC.

Code of Hammurabi Is Not The Oldest Set of Laws

Another misconception relating to the Code of Hammurabi is its presumed nature of being the oldest set of codified laws in human history. However, that is not true from the historical perspective, with the honor (of the oldest law code) probably belonging to the Code of Ur-Nammu, which was inscribed circa 2100 – 2050 BC. Moreover, there is another Sumerian Code of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin that was possibly drawn up at least two centuries before the Code of Hammurabi.

Now, in spite of the relative ‘late-coming’ of the Code of Hammurabi, its influence in the latter laws and dictum penned in the Biblical context is quite unmistakable. As a matter of fact, while the laws of Hammurabi were partly inspired by the aforementioned preceding inscriptions, the core nature of these directives was pretty different from the earlier codes.

To that end, the Code of Hammurabi is quite strict and even vengeful in its approach, with ‘scaled’ laws that were applicable in a variable manner to different social classes. This certainly contrasts with the earlier Sumerian-Akkadian times, where all the communities seemingly had an equal footing under a singular god.

However, by Hammurabi’s time, the concept of a homogeneous society was long forgotten, with different tribes, leaders, and pseudo-religious orders vying for power. In that regard, the strictness of the Code of Hammurabi was possibly a reactionary measure to prevent such blood feuds and incessant conflicts between variant factions.

An Enlightening Start To The Code of Hammurabi

In the previous entry, we talked about how the Code of Hammurabi might have been stricter when compared to the other ancient law codes. However, from Hammurabi’s own perspective, his comprehensive code stood for the dolling out of ‘righteous’ justice that covered every stratum of the Babylonian society. To that end, the prologue to the code starts out by making various enlightening claims, exemplified by Hammurabi’s own words –

“Anu and Bel called by naming me, Hammurabi, the exalted prince, who feared God, to bring about the rule of righteousness in the land, to destroy the wicked and the evil-doers; so that the strong should not harm the weak; so that I should rule over the black-headed people like Shamash, and enlighten the land, to further the well-being of mankind. Hammurabi, the governor named by Bel, am I, who brought about plenty and abundance.”

Some Laws Are Quite Harsh and Even Bizarre

But in spite of magnanimous claims of being ‘enlightening’, suffice it to say – many of the laws in the Code of Hammurabi are simply severe (and in some cases, even disturbing). An apt example is a famous quote from the Biblical context – ‘An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth’, which is just a paraphrasing of a few Hammurabi laws inscribed in the code. Such incidences of lex talionis (retaliation authorized by the land’s law) are also exemplified by some of these other laws in the Code of Hammurabi –

If any one is committing a robbery and is caught, then he shall be put to death.

If a tavern-keeper (feminine) does not accept corn according to gross weight in payment of a drink, but takes money, and the price of the drink is less than that of the corn, she shall be convicted and thrown into the water.

If a son of a paramour or a prostitute says to his adoptive father or mother: “You are not my father, or my mother,” his tongue shall be cut off.

If a son strikes his father, his hands shall be hewn off.

If a man knocks out the teeth of his equal, his teeth shall be knocked out.

If a builder builds a house for someone, and does not construct it properly, and the house which he built falls in and kills its owner, then that builder shall be put to death.

Laws Were Different For the Different Social Classes And the Genders

As we fleetingly mentioned before in one of the entries, the Code of Hammurabi was in many ways a reactionary measure initiated by the state to keep its check on the contemporary feuds and rivalries. During such tumultuous times in the region of Mesopotamia, the draconian laws unsurprisingly favored the authoritative class over the subservient social classes. One apt example of such state-sponsored partisan resolutions can be gathered from this particular law –

If any one steals cattle or sheep, or an ass, or a pig or a goat, if it belonged to a god or to the court, the thief shall pay thirty fold; if they belonged to a freed man of the king he shall pay tenfold; if the thief has nothing with which to pay he shall be put to death.

Furthermore, some laws were bluntly gender-biased, with statutes generally tending to favor free men over women for the same crime. Some even took the drastic route that only required accusation instead of actual crime –

If a man’s wife has the finger pointed at her on account of another, but has not been caught lying with him, for her husband’s sake, she shall plunge into the sacred river.

But it should also be noted that free men didn’t have it all easy –

If a man has struck a free woman with child, and has caused her to miscarry, he shall pay ten shekels for her miscarriage. If that woman dies, his daughter shall be killed.

Some Laws Were Also Quite Progressive

While such laws and morality scopes were directly dictated by the state, especially when concerning household and family relationship matters, the Code of Hammurabi was surprisingly progressive in other areas. To that end, the Code laid down simple yet fair directives when it came to divorce, restriction of dowries, property rights, and the prohibition of incest. One good example of ‘fairness’ is showcased by this particular law that was to take effect in case of climatic emergency –

If any one owes a debt for a loan, and a storm prostrates (kills) the grain, or the harvest fail, or the grain does not grow for lack of water, in that year he need not give his creditor any grain; he washes his debt-tablet in water and pays no rent for this year.

But the ‘piece de resistance’ of progressiveness in the Code of Hammurabi was epitomized by the rough minimum wage laws that initiated compulsory compensations for different occupations. For example, field laborers and herdsmen had to be paid in kind at least ‘eight gur of corn per year’, while ox drivers and sailors had to pay ‘six gur of corn per year’.

The status of doctors was far higher, with his minimum monetary compensation pertaining to five shekels for healing a freeborn man; though this charge was lowered to three shekels for a freed slave and two shekels for a slave.

The Institutionalization of Slavery

If one contemporary social aspect can be gathered from the Code of Hammurabi, it is the state’s institutionalized ill-treatment of the slaves. This grievous scope once again mirrors the turbulent times when Hammurabi had to contend with the numerous factions that had recently come under his sway.

In fact, most of these slaves were former prisoners of war (and their families) who were forcefully inducted into the newly-forged Babylonian society. Here are some of the laws that aptly exemplify the unfair attitude toward the slaves –

If a man has destroyed the eye of a man of the gentleman class, they shall destroy his eye. If he has destroyed the eye of a commoner, he shall pay one mina of silver. If he has destroyed the eye of a gentleman’s slave, he shall pay half the slave’s price.

If a slave has said to his master, “You are not my master,” he shall be brought to account as his slave, and his master shall cut off his ear.

Moreover, owning slaves as property was considered a serious business, and as such the punishments in the Code of Hammurabi were also harsh for such ‘loss’ of property –

If a barber, without the knowledge of his master, cuts the sign of a slave on a slave not to be sold, the hands of this barber shall be cut off.

If the surgeon has treated a serious injury of a plebeian’s slave, with the bronze lancet, and has caused his death, he shall render slave for slave.

Presumption of Innocence Taken To An Extreme Level

While we have previously established how the Code of Hammurabi oscillates between being ridiculously severe and oddly progressive, it is interestingly one of the very few ancient law codes that gave importance to the dictum of ‘innocent until proven guilty’.

In that regard, the Code of Hammurabi might have even played a crucial role in influencing the legal precedents set in our modern times. However, this presumption of innocence more often than puts the burden of proof on the accuser – sometimes taken to an extreme level. This particular statute pretty much proves how accusing someone of a crime was not taken lightly –

If any one brings an accusation of any crime before the elders, and does not prove what he has charged, he shall, if it be a capital offense charged, be put to death.

Hammurabi Was Known More As A Builder And A Conqueror Than A Law-Giver

Now while this may seem anti-climactic to some, historians are still not sure of how the laws in the Code of Hammurabi were used practically in a dynamic society with so many variant parameters (including its respective factions, their tribal connections, political influences, and even deities).

Furthermore, it should be noted how the majority of the population might have been illiterate – and as such, the law in effect was only interpreted in accordance with the personal preference of the local judge (or any authority figure).

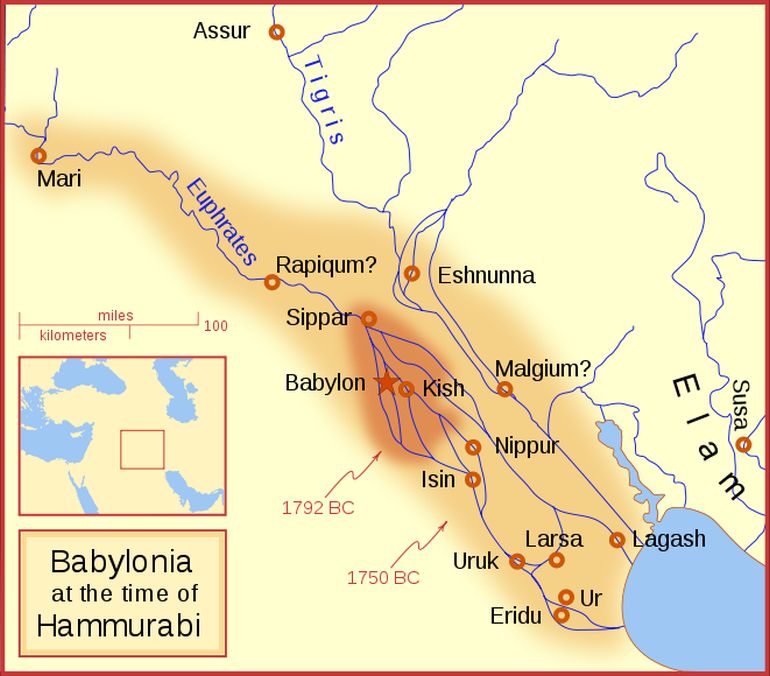

But more importantly, Hammurabi burst into the political scene of Babylon by not only succeeding his father Sin-Muballit (who was probably forced to abdicate) but also continuing his father’s legacy in upgrading the city state’s infrastructure.

Such massive projects ranged from enlarging and heightening the walls of the city and building expansive canals, to constructing ostentatious temples in honor of his patron gods. As a matter of fact, Hammurabi’s patronage of extensive infrastructural endeavors earned him the title of bani matim or the ‘builder of the land’.

However, beyond just popular civic projects, Hammurabi was a very ambitious ruler who long coveted the proximate lands of the resource-rich Mesopotamia. So, one by one, the king made alliance pacts with other city-states to conquer his targeted kingdoms.

But when the task was achieved, the pact was promptly broken, and the previous ally was made the next target. Such an opportunistic military trend continued until Hammurabi was the master of the entire southern part of Mesopotamia – an enviable feat since he initially started with only around 50 sq miles of land under his rule.

In the following years, he conducted campaigns against the rival (and very powerful) city-state of Mari in Syria; and by 1761 BC, entirely destroyed the city. And by 1755 BC, he directly marched onto Ashur and conquered Assyria, thus becoming the ruler of the entire Mesopotamia.

Consequently, the acquisition of so many lands, cities, and their different social constitutions might have prompted the initiation of the Code of Hammurabi – a ‘universal’ law system that could rigorously deal with the divisive nature of the now-expanded Babylonian Empire.

The Code of Hammurabi Was Not Even Found in Babylonia

Now in spite of all the brouhaha and debate over the Code of Hammurabi, the famous diorite stele (mentioned in the first entry) was only unearthed after more than 3,600 years of its founding. The momentous discovery was made in 1901, when a team of French archaeologists unearthed the stele at the ancient city of Susa, Iran, which was once the royal capital of the Elamite Empire (based in present-day Khuzestan, Iran).

Now in terms of history, the Code of Hammurabi stele was looted by the Elamites when their King Shutruk-Nahhunte made a successful raid against the Babylonian city of Sippar in the 12th century BC. He probably even managed to erase some columns from the inscriptions, to make room for his own statutes. But he didn’t go through with his plans, thus maintaining the ‘native’ quality of the Code of Hammurabi.

*The post was updated on 6th September 2019.

Sources: USHistory.org / GMU.edu / Louvre

Be the first to comment on "The Code of Hammurabi: 10 Things You Should Know"