Introduction

As we have discussed previously in many of our mythology-covering articles, the pantheons of most historical cultures were dynamic rather than static. Simply put, the deities and their narratives evolved with time. Such a complicated state of myths and polytheistic mode of worshipping certain gods were even more pronounced in the Mayan culture.

This was partly due to the autonomous state of numerous Mayan city-states – many of which tended to venerate their ‘localized’ deities (much like the Mesopotamians). To that end, it is estimated that the Mayans worshipped over 150 to 250 deities, with some having older Mesoamerican origins while others ‘conceived’ during the Late Postclassic Period (i.e., after circa 900 AD till the early 16th century).

Furthermore, interestingly enough, the Mayan religion didn’t accord many Mayan gods with ‘godly’ characteristics (for the most part). In essence, the deities of the Maya pantheon were treated as supernatural entities, who while being powerful, could also be tricked and even killed by the cunning mortals. In any case, in this article, we will aim to cover some of the major Mayan gods and goddesses who were venerated across most city-states.

The major sources pertain to the Madrid Codex and the Dresden Codex – two of the pre-Columbian Mayan books dating from circa 900-1550 AD. Other sources include the Popol Vuh, a sacred Maya text that covers the creation myths and other related lore of the Kʼicheʼ people, who inhabited the Guatemalan Highlands.

It was later transcribed and translated into Spanish in the early 18th century. Also, note that in scholarly texts many of the gods and goddesses of the vast Maya pantheon have their letter-based designations (like God B or God D).

Contents

- Introduction

- Itzamna – The Ruler of the Heavens

- Ix Chel – The Mayan Moon Goddess

- Kinich Ahau – The Yucatec Maya Sun God

- Chaac – The Mayan Rain God

- Yumil Kaxob – The Mayan God of Flora

- Yum Cimil – The Yucatec Mayan God of Death

- Yum Kaax – The Mayan God of Forests

- Hun Hunahpu – The Popular Maize God Figure

- Huracan – The God of Storms and Chaos

- Ix Tab – The Mayan Goddess Associated with the Moon or Suicide

- Acan – The God of Intoxication

- Ek Chuaj – The Mayan Merchant God of Cocoa

- Kukulkan (or Gucumatz) – The Plumed Serpent

- Honorable Mention: Camazotz – The Bat Monster

Itzamna – The Ruler of the Heavens

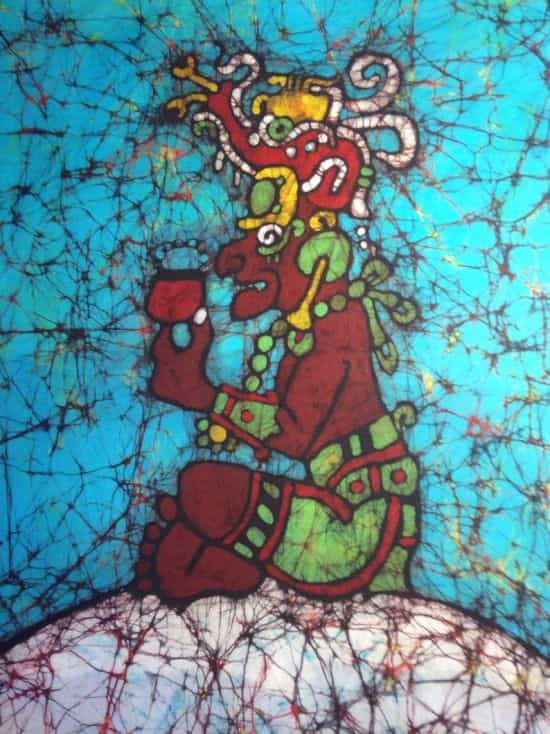

Itzamna (Itzamná or Itzam Na, also called God D) was counted among one of the most popular Mayan deities in the pre-Columbian pantheon He was designated as the king of heaven and night and day.

In the mythical narrative, his rulership over these vast (and seemingly contrasting) domains is ‘powered’ by innate and even arcane knowledge, as opposed to supernatural strength and unquestioned royalty. To that end, he was often portrayed as a toothless old man with an amiable demeanor, hooked nose, large eyes, and a cylindrical hat – alluding to his leadership qualities.

In some instances, he is presented as the son of the mighty yet capricious creator god Hunab Ku who brought about floods to end the race of humans. Contrastingly, Itzamna poses as an antithesis of his father, since he aids the ancient Maya people by inventing writing, sacred calendar systems, agriculture, science, and Maya medicine. This suggests that mythically, Itzamna also played his part in creating human beings.

Simply put, he was perceived as a cultural hero who laid down the foundations of a civilization that was to flourish later. And talking of relations, Itzamna is also identified as the husband (counterpart) to Ix Chel (or Goddess O) – and together they were venerated as the couple that gave birth to an entire generation of powerful gods.

Interestingly enough, in terms of etymology, Itzamna means ‘lizard’ or ‘big fish’ in the Mayan language, with the prefix Itz also alluding to divinity, foretelling, and even witchcraft in other associated Mesoamerican languages.

To that end, Itzamna is also called by other names, including Kukulkan (feathered serpent deity), and is represented as a two-headed serpent or even as a hybrid creature with both human and lizard (or caiman) like features.

Ix Chel – The Mayan Moon Goddess

Ix Chel (or Ixchel, also called Goddess O and sometimes associated with Goddess I) was an important feminine deity in the Mayan pantheon (from both the Classic and Late Postclassic Periods, circa 250 – 1550 AD).

Often termed the ‘Lady Rainbow’, the goddess is associated with the moon, weather, fertility, children, and health. Interestingly enough, much like her aforementioned male-counterpart Itzamna, Ix Chel, in the mythical narrative, was known for her dual aspect.

For example, Ix Chel as Goddess I was represented as a young and beautiful seductress who espouses fertility, marriage, and love. In this aspect, she was associated with both lunar cycles and rabbits and was often given epithets like Ixik Uh (‘Lady Moon’).

Historically, the eminence of the deity as one of the important goddesses can be discerned from her portrayals in artworks and cult centers. To that end, Mayans possibly made the pilgrimage across the Caribbean in ceremonial canoes to one of her temples on Cozumel Island – currently the ruins at San Gervasio.

On the other hand, as Goddess O, Ix Chel (or a deity who was similar to the goddess Ix Chel) was represented as a wizened old woman who had the power to both create and destroy the earth. Counted among the powerful gods in the Mayan pantheon, Goddess O was also depicted with claws, fangs, and a red body adorned with death symbols and skulls – and this embodiment was called Chac Chel (‘Red Rainbow’).

Kinich Ahau – The Yucatec Maya Sun God

Kinich Ahau (or Ahaw K’in, also known as God G) was the name for the Sun God of the Yucatec Mayans (the Maya people of the Yucatan), and as such, the prefix element kʼinich may have meant ‘sun-eyed’, possibly referring to a royal lineage during the Classic Period (circa 250 – 900 AD).

Interestingly enough, in some cases, given his association with an element of the sky, the Mayan god is also regarded as an aspect of Itzamna, the aforementioned ruler of the heavens. To that end, in one mythical narrative, Ix Chel, the moon goddess, impresses him by wearing a fine woven dress, and the two finally become lovers (although their relationship later turns tumultuous).

As for depictions, Kinich Ahau, befitting his regal status (as one of the important gods), was often represented with a hooked nose, squared large eyes, and even a beard. And like other comparable Mayan deities, the great god was also represented differently (or in a dual manner) in some codices, like an old man with crooked teeth (in the Madrid Codex).

Incredibly enough, he was also associated with the jaguar in the Maya culture, as it was believed that the sun god transformed into the feline predator (with huge jaguar skin and jaguar ears) during the night. Moreover, Kinich Ahau was further venerated as the patron god of the day unit (since he embodied the sun) and the Number Four.

Chaac – The Mayan Rain God

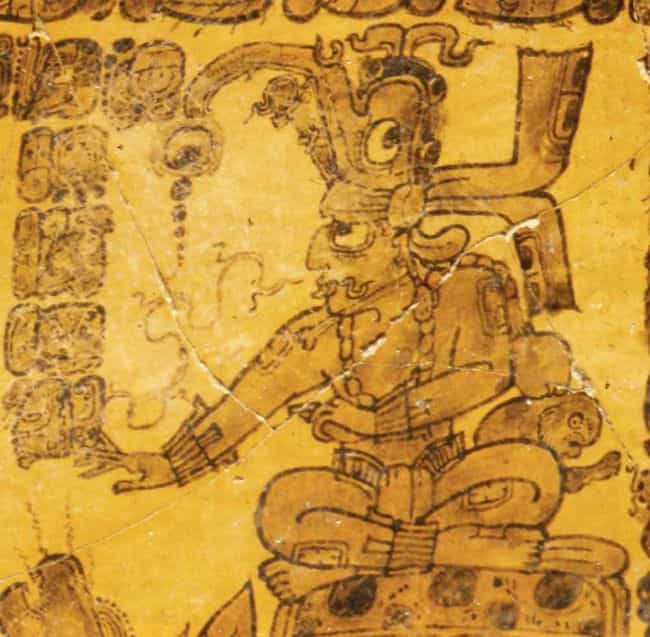

Chaac (Chac or Chaakh, also known as God B) was the Mayan deity of rain – thus making him a very important figure in the agricultural civilization of the Maya. In addition, he was also venerated as the god of thunder and storms – with one particular myth-based motif suggesting how he struck the clouds with jade axes (and even snakes) to bring down the rain.

Such mighty actions nourished the various crops (especially the maize, which is often ascribed as a gift of Chaac to the Maya people after he discovered the seedling inside the rock) and fostered the natural cycle of life in terms of regeneration.

Now in terms of history, it should be noted that Chaac probably played his symbolic role in human sacrifices made by the Mayan priests atop the pyramid temples. To that end, some of the attendants who held the victims might have even dressed as Chaac, to represent the four cardinal directions.

As for the myths of Maya culture, he is presented as the brother of the sun god Kinich Ahau. And while these brothers were close, Chaac fell for the beautiful wife of Kinich Ahau (possibly Ix Chel) and consequently suffered punishment for his immoral affair. To that end, few Mayan legends say how the rain occurs when Chaac cries for repentance – thereby contradicting the ‘ax-effect’ on clouds (as was sometimes the case in various myths).

In any case, many Mayan kings were venerated as ‘rainmakers’, thereby underlining their strong relationship to Chaac – the Mayan rain god. Interestingly enough, in spite of being the rain gods, the (plural) Chaacs were believed to dwell not in the skies but deep within the caves and cenotes – signifying the sources of water. In that regard, his Aztec (Nahuatl) counterpart is often perceived as Tlaloc – who was correlated with caves, springs, and mountains.

Yumil Kaxob – The Mayan God of Flora

Yumil Kaxob (meaning ‘Owner of Crop’) was possibly venerated as the Mayan god of flora. In many ways, he was perceived as the essence or power residing within the crops (like maize) that allowed them to grow, ripen, and ultimately sustain the Maya people.

To that end, Yumil Kaxob was often also associated with the Maize God. In some narratives, he is also represented as the son (or essence) of Chaac – and the father-son duo works together to bring forth rain and crops for the agricultural folks.

So, in many ways, Yumil Kaxob was venerated as an aspect of the life force that resides within the flora. Consequently, during times of drought, it was believed that Yumil Kaxob was ‘killed’ by the Mayan god of death Yum Cimil (discussed later).

However, like the proverbial phoenix, Kaxob had the undefeatable power of rejuvenation, which after a passage of time made him rise from his death, thereby once again completing the natural cycle.

Yum Cimil – The Yucatec Mayan God of Death

Things get a bit complicated when it comes to the mythical scope of the Mayan gods of death. The reason is that there are quite a few deities that were associated with the aspect of death, with the significant ones pertaining to Yum Cimil (‘Lord of Death’) in Yucatec and Ah Puch (or Ah Pukuh) in Chiapas.

The name Ah Puch, however, is sometimes demoted by academia, possibly because of the lack of authenticity when it comes to the name. In Popol Vuh, entities of death like Hun-Came (‘One Death’) and Vucub-Came (‘Seven Death’) are mentioned – both of whom are incidentally defeated by the mortals.

As for Yum Cimil, the ‘fleshless god’, espousing the state of decay, was represented with his skeletal mask, protruding belly (filled with rotting matter), body adorned with bones, and a neckless bedecked with eyeless sockets.

In some narratives, he rules over the nine underground worlds known as Mitnal. Inside this hellish realm, Yum Cimil takes sadistic pleasure in extinguishing the very essence of souls by torturing them with fire and water.

Interestingly enough, his counterpart (or another aspect) Ah Puch or God A, in spite of his deathly ‘air’, has some comical (or scatological) elements attached to him, few dealing with flatulence and anus. But beyond dark humor, Ah Puch – as one of the death gods was possibly seen as the opponent to the god Itzamná – the aforementioned god of life.

Yum Kaax – The Mayan God of Forests

Referred to as the son of Itzamna and Ix Chel in some myths, Yum Kaax (‘Lord of Forests’) was possibly counted among the youngest of Mayan gods and goddesses. And interestingly enough, while he is often represented with motifs of corn (sometimes in the form of a headdress), Yum Kaax is not to be confused with the Corn God (or God E). Rather the deity, as the name suggests, was probably venerated as the guardian of the forest and protector of wildlife – both flora and fauna.

Often depicted with an elaborate corn headdress and corn cob pots in his hand, Yum Kaax was possibly worshiped by both farmers and hunters. The former connection alludes to how the Mayan god was also revered as a deity of agriculture – so much so that many offered their first fruits to the deity of the forest.

As for the latter, the hunters had to offer special prayers and rituals that asked for the permission and guidance of Yum Kaax pertaining to the species of the hunt (especially when hunting deer).

Hun Hunahpu – The Popular Maize God Figure

Hun Hunahpu (or ‘Head Apu I’) was venerated as a tragic figure in the Maya religion, who was more important culturally because of his two sons – the twin heroes Hunahpu and Xbalanque. In the most prominent tale, Hun Hunahpu and his own brother were tricked by the Mayan gods of death (in a ball game) and then sacrificed.

His head was hung as a trophy on a calabash tree. However, Hun Hunahpu’s head, still having its ‘godly’ sentience, spat on a passing young woman – thereby impregnating her with his saliva (signifying the juice of calabash). Subsequently, she gave birth to the twin heroes Hunahpu and Xbalanque, who avenged their father by defeating the gods of the underworld (Xibalba).

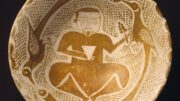

Unfortunately, the twins were not able to resurrect their father after recovering his head. However, symbolically, the Mayans (of the Classical Period) believed that Hun Hunahpu was reborn as maize. The interpretation of one particularly significant scene of the Tonsured Maize God arising from the Turtle Shell (earth) sheds light on this aspect of Hun Hunahpu – as the resurrected maize deity.

Huracan – The God of Storms and Chaos

Residing in the endless sky, Huracan (or U Kʼux Kaj, ‘Heart of Sky’, sometimes called God K) as one of the major Mayan gods was believed to be the primordial force unleashed by the dual divinities – Tepeu and Gucumatz, as mentioned in the Popol Vuh. This chaotic force was needed by the creator gods to ‘chisel out’ the order of creation and its manifestation on the physical plane.

Simply put, Huracan (like the Hindu god Shiva) was regarded as the antithetical being whose essence and behavior ironically lead to the survival of life. One example would pertain to a mythical narrative that surmises how it was Huracan who sent a Great Flood to wipe out an entire generation of humans and invoke the Earth for renewal of life.

Given his immense power and chaotic origins, Huracan was often associated with lightning, wind, and storms – with the former often perceived as a manifestation of both fire and fertility.

Interestingly enough, in some tales, Huracan is the one who split open the mountains with his lightning to reveal the hidden maize seed, thereby leading to the agricultural prowess of the Maya people. As for depictions, the Mayan storm god was represented with a ‘branching’ nose (signifying his power) and a leg that transformed into a serpent at the end.

Ix Tab – The Mayan Goddess Associated with the Moon or Suicide

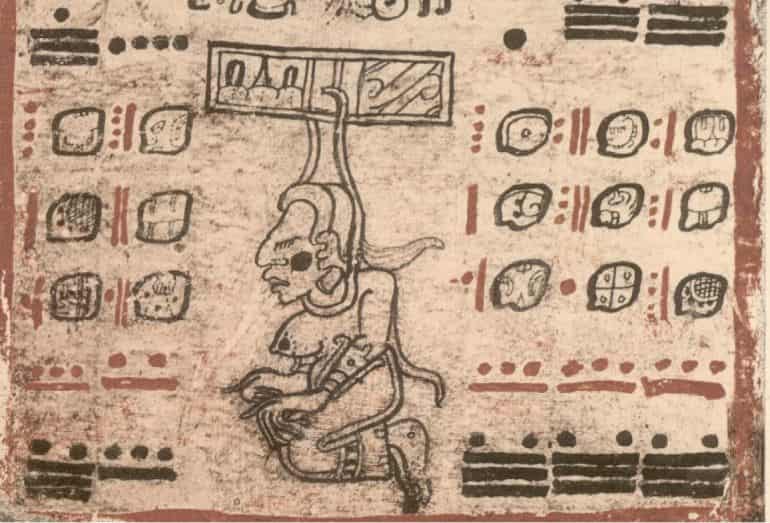

Incredibly enough, the Dresden Codex contains a relatively graphic image of a dead (or passed out) woman with a rope around her neck hanging from the celestial sky band (pictured above) – and this mythical motif is often perceived as the representation of Ix Tab, the Mayan goddess of ‘suicide’.

To that end, the very connection between the act of suicide and a Mayan deity was probably first made by 16th-century Spanish bishop Diego de Landa. He went on to hint at how in Mayan circles, suicide committed due to depression, sickness, or pain was seen in a relatively positive light, and as such, the deceased person was allowed to the gloria (heaven), often accompanied by Ix Tab, the goddess of the gallows.

However, on closer inspection of the Dresden Codex, the image of the ‘hanged’ woman is represented in the section dealing with eclipses – and as such, this particular portrayal may have signified the occurrence of a lunar eclipse (the ‘dead’ moon being personified by a dead or paralyzed person or goddess hanging from the sky).

As for another hypothesis, Ix Tab might have been the female version of Ah Tab (or Ah Tabay) – a minor Mayan god of hunting associated with snaring or deceiving. Consequently, his female counterpart was possibly regarded as the benevolent ‘hangwoman’ who was also associated with snares.

Acan – The God of Intoxication

Often associated with alcoholic brews, Acan (or Akan) was regarded as one of the Mayan gods who reveled in boisterous celebrations and drinking. Unsurprisingly, he was the patron of balche, a Mesoamerican cocktail made from fermented honey and the bitter bark of the Blache tree. Essentially, Acan was possibly perceived as the divine ‘party animal’, thus mirroring his Greek and Roman counterparts like Dionysus and Bacchus.

Interestingly enough, the Mayans themselves may have regarded this state of inebriation (or ‘drunkenness’) as being closer to the patron god Acan. There were even instances where priests and officials would get ‘high’ on other substances ranging from tobacco and morning glory seeds to mushrooms.

In some cases, Acan was also represented as a close friend (or aspect) of Cucoch, the Mayan god of creative endeavors, thereby also underlining how artistic flair was seen as an extension of recreational activities.

Ek Chuaj – The Mayan Merchant God of Cocoa

Ek Chuaj (or God M) was a Postclassic Mayan deity who was venerated as the patron of both merchants and cocoa. He was possibly also perceived as the protector of travelers among the Maya gods, as can be discerned from his depiction of objects such as a pack and spear.

Talking of depictions, EK Chuaj was usually showcased as a deity who had stripes of black and white or was entirely black (Madrid Codex). His mouth was lined by a red-brown border, while his lower lip was large and drooping.

In Maya culture, cocoa (cacao) was treated as a currency. Thus by extension, Ek Chuaj, as a merchant god, was seen as the patron of cocoa traders and cocoa grove owners. In that regard, many such traders even held festivals in honor of the merchant god, particularly during the month of Muwan.

Kukulkan (or Gucumatz) – The Plumed Serpent

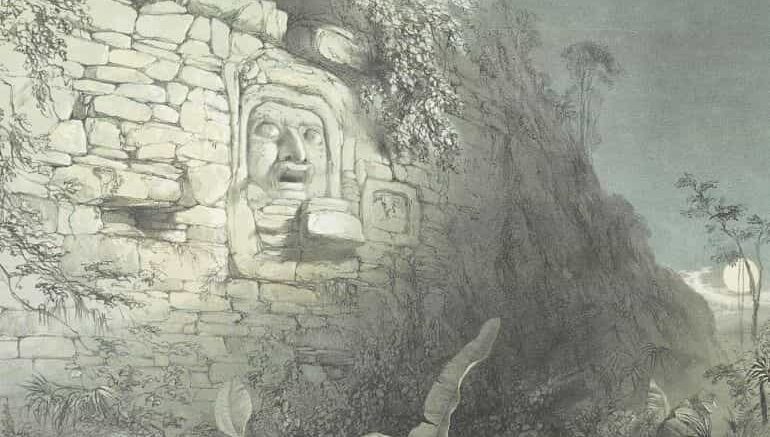

Also known as the Feathered Serpent (Quetzalcoatl in Aztec mythology), the origins of Kukulkan go back to the Late Preclassic Period, as is evident from the representation of the serpent god found at the Olmec site of La Venta.

The stela, dating from some time between 1200 – 400 BC, portrays a serpent rearing its head behind a person (possibly a priest). More elaborate depictions of the serpent version are found in the six-tiered Mayan pyramid built in the god’s honor at Teotihuacan, dating from circa 3rd century AD.

Incredibly enough, given the diversity of cultures in Mesoamerica and the ever-evolving nature of myths and lore, Kukulkan, as a central figure, was also portrayed in forms that went beyond the morphology of serpents.

For example, dating from circa 700 – 900 AD, there are a few representations of Kukulkan, especially from the site of Xochicalco (a pre-Columbian site that was settled by Mayan traders) that are distinctly human in form. A few of them were possibly even inspired by human rulers who carved their legacy through influence and conquests.

In any case, the cult of the Feathered Serpent God – who was called Kukulkán by the Yucatec Mayans (possibly having its origins in Waxaklahun Ubah Kan, the War Serpent or the even older Vision Serpent) and Gucumatz (or Qʼuqʼumatz) by the Quiché of Guatemala endured in the Mesoamerican sphere for around 2,000-years.

Its center of worship probably pertained to Teotihuacan, the largest city in the pre-Columbian Americas, by circa 1st century AD. And after the fall of Teotihuacan by circa early 7th century AD, the obeisance of the ‘Feathered Serpent’ didn’t stop but rather spread to other Mesoamerican urban centers, including Xochicalco, Cholula, and even Chichen Itza of the Maya world – as could be discerned from the iconography of the period.

The question can be raised – why was the deity particularly associated with a serpent? Well, according to some scholars, the snake in its most basic form in Mesoamerican culture might have represented the earth and the vegetation.

Archaeologist Karl Taube hypothesized that the feathered serpent, by virtue of its ‘evolved’ morphology, may have been associated with fertility as well as the intricate political classes of the region.

Honorable Mention: Camazotz – The Bat Monster

While not exactly counted among the Mayan gods, Camazotz was sometimes merged with godly entities, like in the case of the Zotzilaha Chamalcan, the fire god of the K’iche’ (Quiche) Maya people of Guatemala.

However, in Popol Vuh, Camazotz is the name attributed to humanoid bat-like creatures (or rather vampire-like entities or gods of death) that are downright dangerous and vicious – so much so that one of them lops off the head of a mortal hero, which is then played with, in a gruesome ball game.

Interestingly enough, in terms of conventional zoology, all of the three known species of vampire bats are actually native to the New World. So, it really doesn’t come as a surprise that it is Mayan mythology that brings forth the legend of a mythical vampire creature.

But the fascinating part is that Camazotz’s legend does have many similarities to the well-known vampire stories of the later eras. In that regard, some narratives do describe Camazotz as a purely evil entity with the sole aim to cause terror.

Similarly, in the myths of the Zapotec people, who ruled over the Oaxaca region, in Mexico, circa 100 AD, bats were the harbingers of night, death, and sacrifice. This macabre association probably comes from the fact that bats were known to inhabit the darker parts of caves around the cenotes.

And such areas were considered ‘portals’ or entry points to the mysterious underworld. Unsurprisingly, in some depictions, Camazotz was represented as holding a sacrificial knife in one hand and a human heart (or victim) in the other.

Note* – The article was updated on 27th April 2022.

Be the first to comment on "The 13 Major Mayan Gods and Goddesses You Should Know About"