Historical reconstructions provide us with a glimpse into the visual scope of the past – more so when such recreations pertain to famous historical personalities. However, one should also note that these reconstructions – fueled by archaeology, detailed analysis of subjects, and technology, are supposed to be credible estimations of the facial structures at the end of the day (as opposed to precise representations). Keeping that in mind, let us take a gander at the visual reconstruction of twelve well-known historical figures, with the time period ranging from the ancient times to the 18th century.

Contents

- Nefertiti (circa 14th century BC)

- Tutankhamen (circa 14th century BC)

- Ramesses II (circa 13th century BC)

- Philip II of Macedon (circa 4th century BC)

- Cleopatra (circa Ist century BC)

- Nero (circa 1st century AD)

- Lord of Sipan (circa 1st – 2nd century AD)

- St. Nicholas (circa 270 – 343 AD)

- Robert the Bruce (1274 – 1329 AD)

- Richard III (1452 – 1485 AD)

- Henry IV of France (1553 – 1610 AD)

- Maximilien de Robespierre (1758 – 1794 AD)

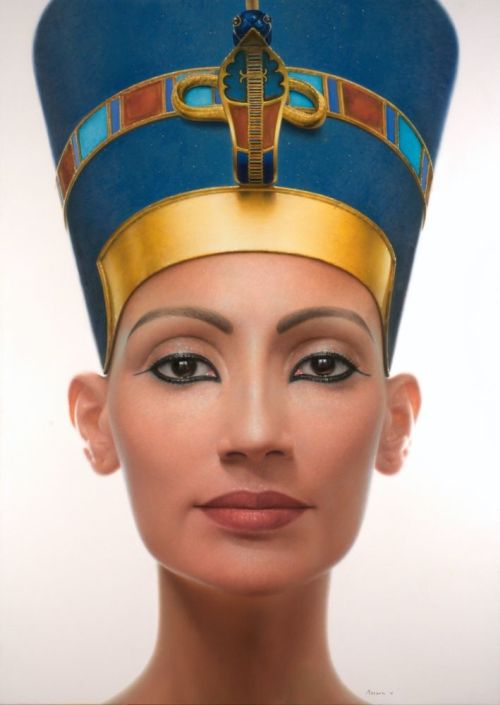

Nefertiti (circa 14th century BC)

More than 1,300 years before the birth of Cleopatra, there was Neferneferuaten Nefertiti (‘the beauty has come’) – a powerful queen from ancient Egypt associated with beauty and royalty. However, as opposed to Cleopatra, Nefertiti’s life and history are still shrouded in relative ambiguity, in spite of her living during one of the opulent periods of ancient Egypt.

The reason for such a contradictory turn of affairs probably had to do with the intentional disassembling and expunging of the legacy of Nefertiti’s family (by successive Pharaohs) because of their controversial association with a religious cult that prescribed the relegation of the older Egyptian pantheon.

Fortunately for us history enthusiasts, in spite of such rigorous actions, some fragments of Nefertiti’s historical legacy survived through various extant portrayals, with the most famous one pertaining to her bust made by Thutmose circa 1345 BC.

The bust with its bevy of intricate facial features favorably depicts the ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertiti, possibly at the age of 25. In terms of the visual look, what we do know about Nefertiti, also comes from the royal portrayals on the numerous walls and temples built during the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep IV.

In fact, the depiction styles (and prevalence) of Nefertiti were almost unprecedented in Egyptian history till that point, with the portrayals quite often representing the queen in positions of power and authority. These ranged from depicting her as one of the central figures in the worship of Aten to even representing her as a warrior elite riding the chariot (as presented inside the tomb of Meryre) and smiting her enemies.

Talking about depictions, reconstruction specialist M.A. Ludwig has taken a shot at recreating the facial features of the famed Queen Nefertiti with the aid of Photoshop (presented above). Based on the renowned limestone Nefertiti Bust, Ludwig makes this point clear about the facial reconstruction (presented above) –

I’ve seen artists try to bring out the living likeness of Queen Nefertiti many times, and some of the most famous attempts, though good in and of themselves, always seem to adjust her facial features to match certain contemporary standards of beauty in some way, which really isn’t necessary because the original bust of Nefertiti is already so beautiful and lifelike. I took the chance of leaving the bust’s features entirely as they are, only replacing the paint and plaster with flesh and bone. The result is absolutely stunning.

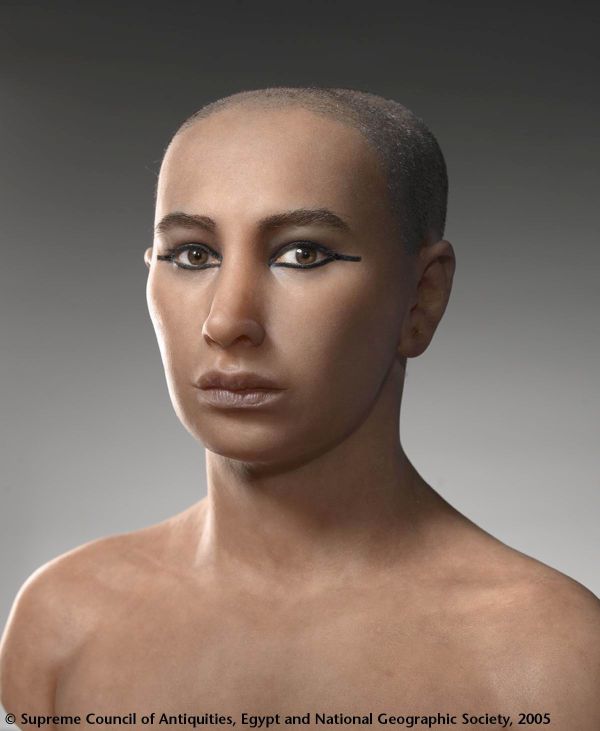

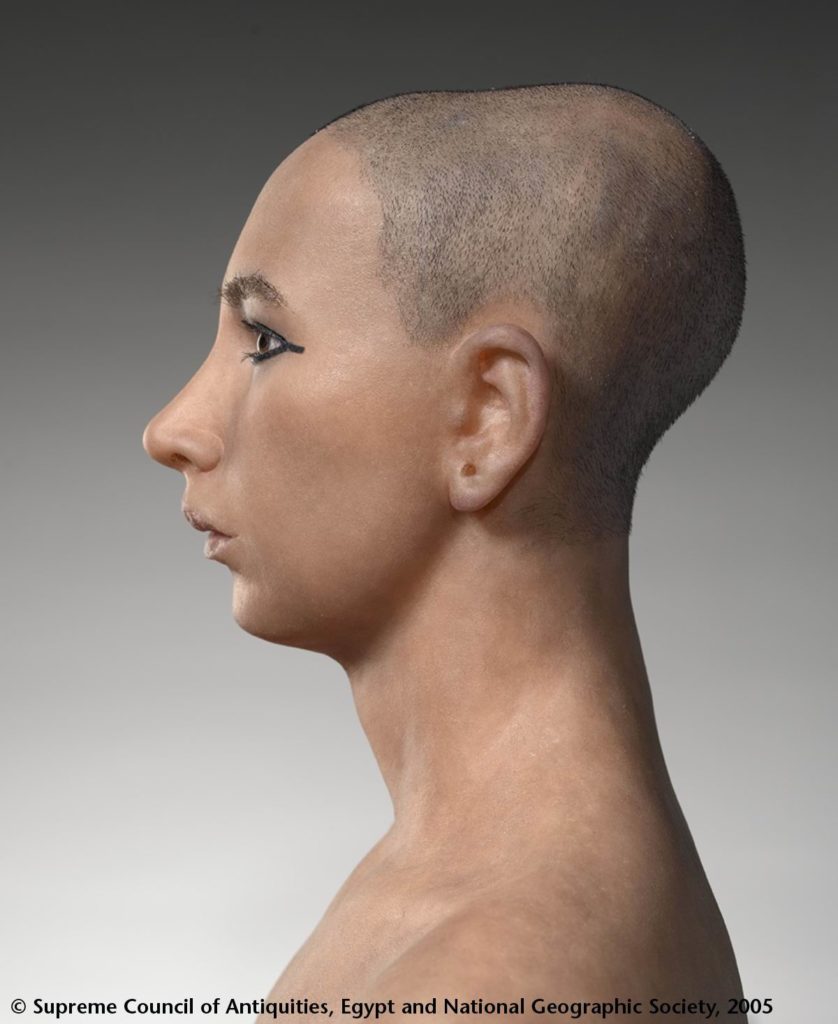

Tutankhamen (circa 14th century BC)

Tutankhamun (‘the living image of Amun’), also known by his original name Tutankhaten (‘the living image of Aten’) was a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty – who only ruled for around a decade from circa 1332-1323 BC.

Yet his short reign was important in the grander scheme of things since this era not only coincided with Egypt’s rise as a world power but also corresponded to the return of the realm’s religious system to the more traditional scope (as opposed to the radical changes made by Tutankhamun’s father and predecessor Akhenaten – the husband of Nefertiti). The legacy of King Tut also has its fair share of mysteries, with a pertinent one relating to his still-unidentified mother, often only referred to as the Younger Lady.

Reverting to his own reconstruction, back in 2005, a group of forensic artists and physical anthropologists, headed by famed Egyptologist Zahi Hawass, created the first known reconstructed bust of the renowned boy king from ancient times. The 3D CT scans of the actual mummy of the young Pharaoh yielded a whopping 1,700 digital cross-sectional images, and these were then utilized for state-of-the-art forensic techniques usually reserved for high-profile violent crime cases. According to Hawass –

In my opinion, the shape of the face and skull are remarkably similar to a famous image of Tutankhamun as a child, where he is shown as the sun god at dawn rising from a lotus blossom.

Controversially enough, in 2014, King Tut once again went through what can be termed a virtual autopsy, with a bevy of CT scans, genetic analysis, and over 2,000 digital scans. The resulting reconstruction was not favorable to the physical attributes of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh, with emerging details like a prominent overbite, slightly malformed hips, and even a club foot.

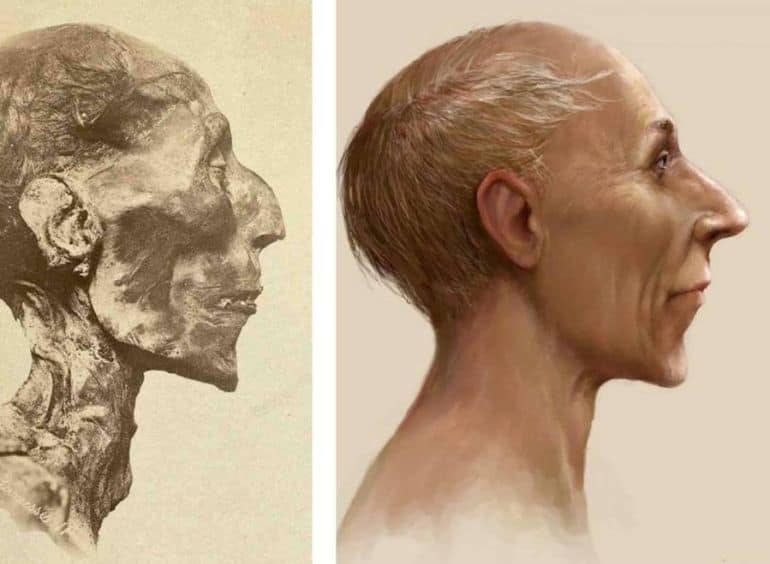

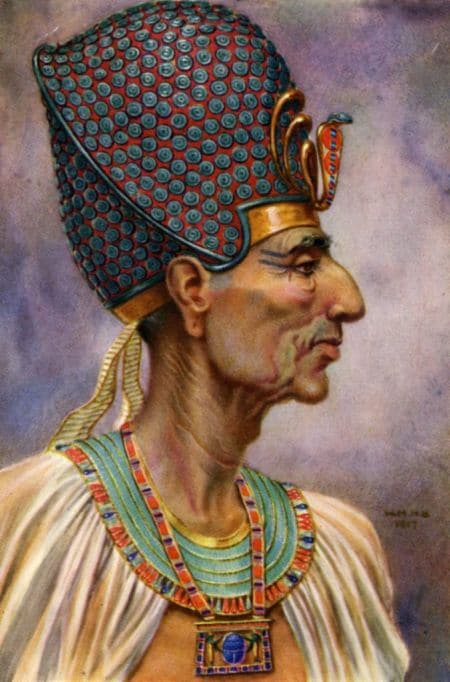

Ramesses II (circa 13th century BC)

Ramesses II (also called Ramses, Ancient Egyptian: rꜥ-ms-sw or riʕmīsisu, meaning ‘Ra is the one who bore him’) is considered one of the most powerful and influential ancient Egyptian Pharaohs – known for both his military and domestic achievements during the New Kingdom era.

Born circa 1303 BC (or 1302 BC), as a royal member of the Nineteenth Dynasty, he ascended the throne in 1279 BC and reigned for 67 years. Ramesses II was also known as Ozymandias in Greek sources, with the first part of the moniker derived from Ramesses’ regnal name, Usermaatre Setepenre, meaning – ‘The Maat of Ra is powerful, Chosen of Ra’.

As for his reconstruction scope, after 67 years of long and undisputed reign, Ramesses II, who already outlived many of his wives and sons, breathed his last circa 1213 BC, probably at the age of 90. Forensic analysis suggests that by this time, the old Pharaoh suffered from arthritis, dental problems, and possibly even hardening of the arteries.

Interestingly enough, while his mummified remains were originally interred at the Valley of the Kings, they were later shifted to the mortuary complex at Deir el-Bahari (part of the Theban necropolis), so as to prevent the tomb from being looted by the ancient robbers.

Discovered back in 1881, the remains revealed some facial characteristics of Ramesses II, like his aquiline (hooked) nose, strong jaw, and sparse red hair. YouTube channel JudeMaris has reconstructed the face of Ramesses II in his prime, taking into account the aforementioned characteristics – and the video is presented above. A painting by Winifred Mabel Brunton also provides an estimation of the side profile of the Pharaoh at a slightly advanced age.

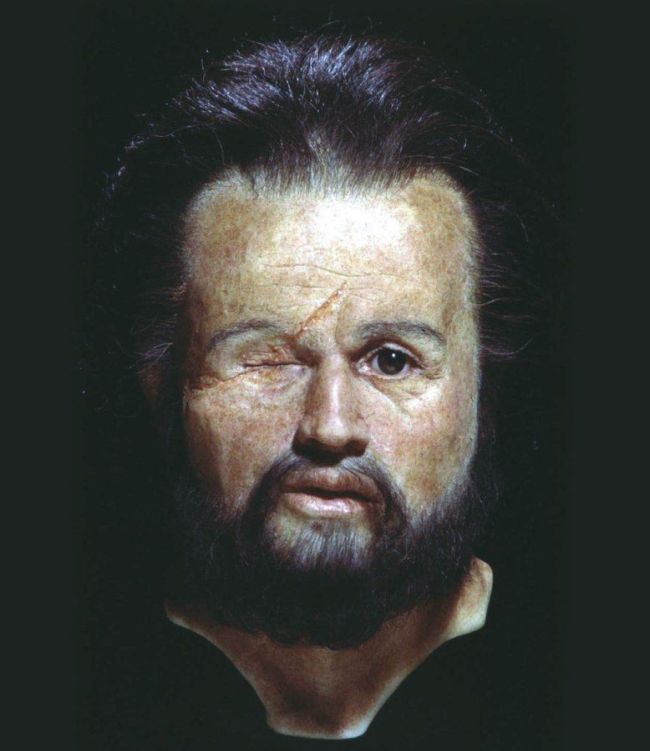

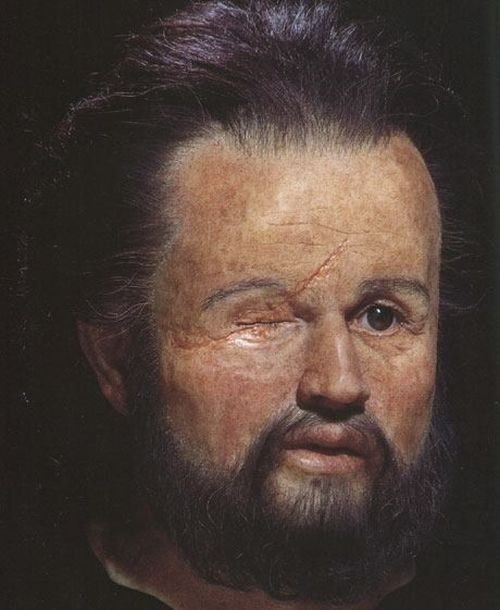

Philip II of Macedon (circa 4th century BC)

While often overshadowed by his son Alexander the Great, Philip II was a crucial figure in Greek history, given his enormous contributions to the stability and military rise of the Macedonian kingdom. In fact when Philip II assumed the reign of the nascent Macedon, the state’s army was all but vanquished – with their earlier king and many of the hetairoi (king’s companions) meeting their gruesome deaths in a battle against the invading Illyrians.

However, impressed by Theban hoplites, the new king initiated military reforms that led to the momentous adoption of the Macedonian phalanx as an effective military formation – that was the lynchpin of the army of Alexander and his Hellenistic successors.

As for the reconstruction, the images are based on the bones that were originally found inside Tomb II, one of the three Great Tombs of the Royal Tumulus at Vergina. Unfortunately, there is an ongoing academic debate over the actual identity of this tomb’s occupant.

One of the accepted hypotheses since the 70s related to how the tomb belonged to Philip. However, recent analysis has shed light on the possibility that the tomb actually belonged to Philip’s son (and Alexander’s half-brother) Arrhidaeus. On the other hand, the bones recovered from Tomb I might have belonged to the actual Philip. JudeMaris has also reconstructed the face of the King of Macedon, as presented in the video below.

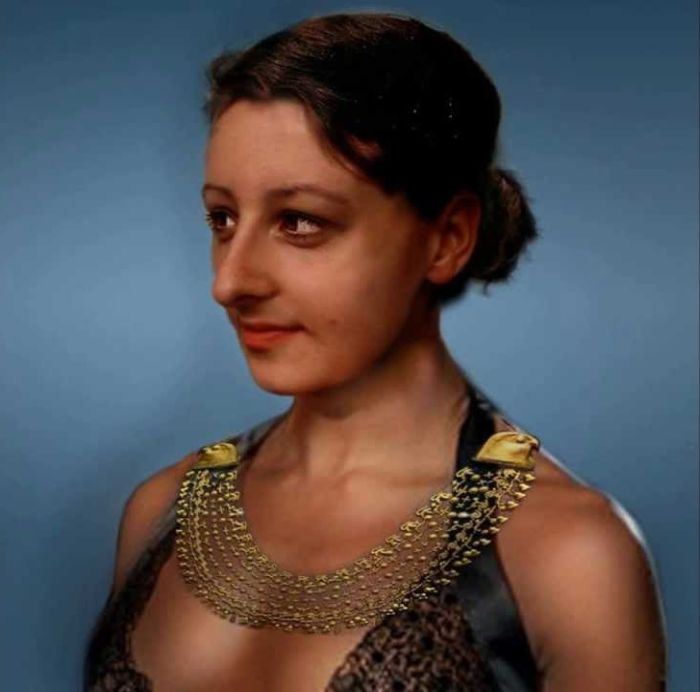

Cleopatra (circa Ist century BC)

Cleopatra – the very name brings forth reveries of beauty, sensuality, and extravagance, all set amidst the political furor of the ancient world. But does historicity really comply with these popular notions about the famous female Egyptian pharaoh, who had her roots in a Greek dynasty?

Well, the answer to that is more complex, especially considering the various parameters of history, including cultural inclinations, political propaganda, and downright misinterpretations. For example, some of our Hollywood-inspired popular notions tend to project Cleopatra as the quintessential Egyptian queen of ancient times.

However, in terms of history, it is a well-known fact that Cleopatra or Cleopatra VII Philopator (Romanized: Kleopátrā Philopátōr), born in 69 BC, was of (mostly) Greek ethnicity. To that end, being the daughter of Ptolemy XII, she was the last (active) ruler of the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty that held its major domains in Egypt.

In essence, as a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty, Cleopatra was a descendant of Ptolemy I Soter, a Macedonian Greek general, companion (hetairoi), and bodyguard of Alexander the Great, who took control of Egypt (after Alexander’s death), thereby founding the Ptolemaic Kingdom. On the other hand, the identity of Cleopatra’s grandmother and mother is still unknown to historians.

As for her reconstruction, one particular sculpture, thought to be of Cleopatra VII, is currently displayed at the Altes Museum in Berlin. Reconstruction specialist/artist M.A. Ludwig made her project based on that actual bust. And please note that the following recreations are just ‘educated’ hypotheses at the end of the day (like most historical reconstructions), with no definite evidence that establishes their complete accuracy when it comes to actual historicity.

And while the animation will undoubtedly confuse many a reader and history enthusiast, actual written records of Cleopatra vary in their tone from a profusion of appreciation (like Cassius Dio’s account) to practical assessments (like Plutarch’s account).

Pertaining to the latter, Plutarch wrote a century before Dio and thus should be considered more credible with his documentation being closer to the actual lifetime of Cleopatra. This is what the ancient biographer had to say about the female pharaoh – “Her beauty was in itself not altogether incomparable, nor such as to strike those who saw her.”

Even beyond ancient accounts, there are extant pieces of evidence of Cleopatra’s portraiture to consider. To that end, around ten ancient coinage specimens showcase the female pharaoh in a rather modest light. Oscillating between what can be considered ‘average’ looking to representing downright masculine features with the hooked nose, Cleopatra’s renowned comeliness seems to be oddly missing from these portraits.

Now since we are talking about history, some of the masculine-looking depictions were possibly part of political machinations that intentionally equated Cleopatra’s power to her male Ptolemaic ancestors, thus legitimizing her rule.

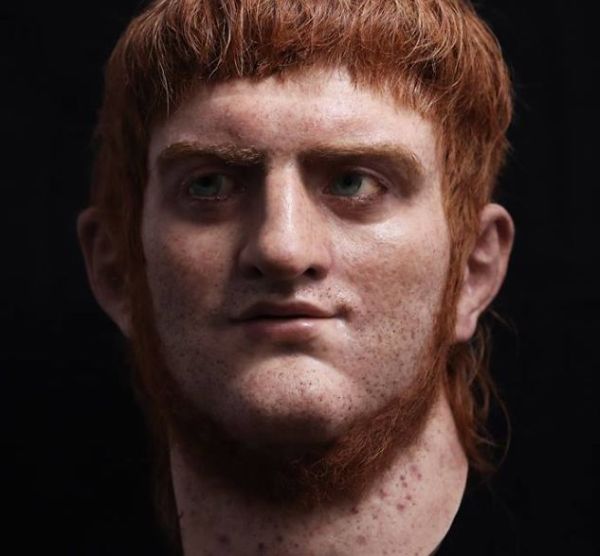

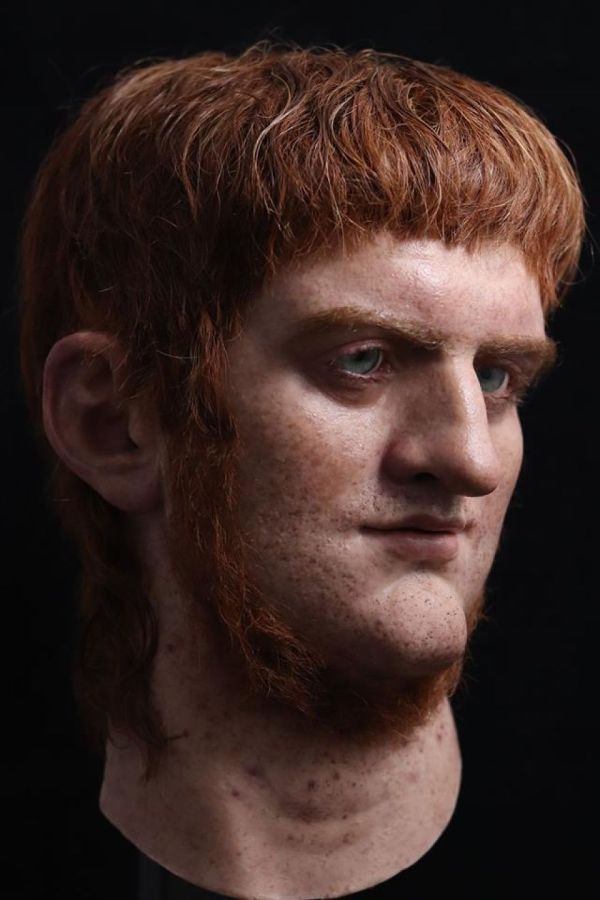

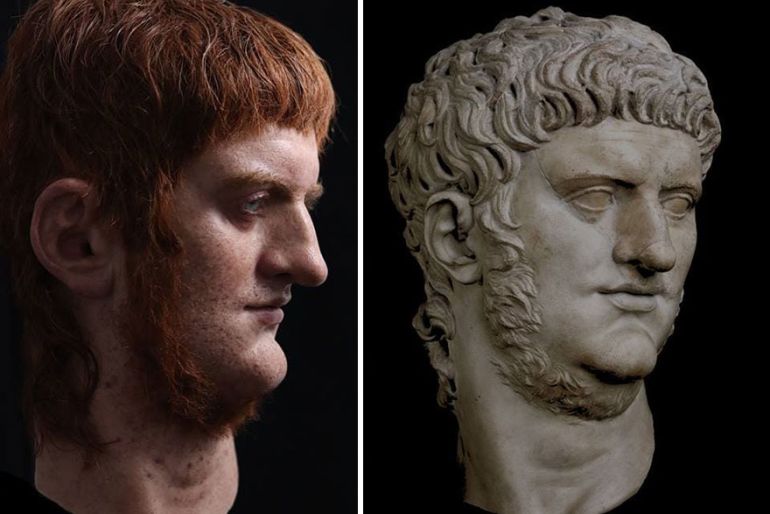

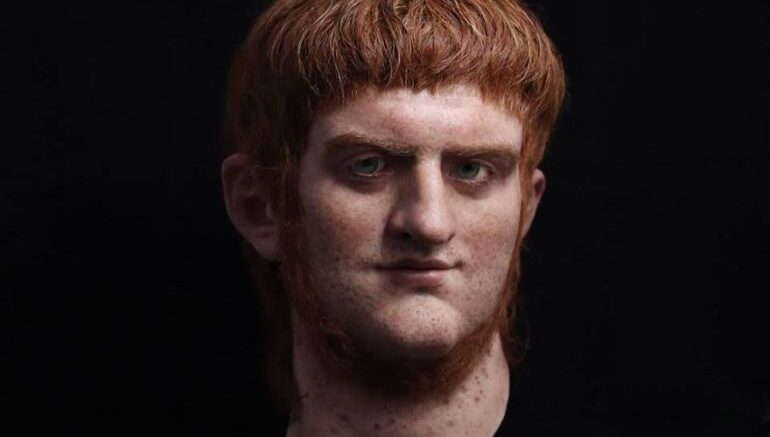

Nero (circa 1st century AD)

Historically, the last emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Nero is probably famous in popular culture for his bouts of tyranny, extravagance, and even eccentricity. To that end, one of the episodes often associated with Nero pertains to how he facilitated the Great Fire of Rome – supposedly so that he could build his ritzy palace, the Domus Aurea (Golden House), in place of the burned-down structures.

And while this account is mentioned by Suetonius, there is no actual evidence to corroborate the ancient claim. Furthermore, while Nero was (probably) perceived as an erratic personality who raised taxes and preferred participation in public performances (including as a pregnant woman), he was also seen in a positive light by the poor masses of Rome.

The reconstruction is entirely based on the bust of Nero kept at the Musei Capitolini, Rome. The recreation was undertaken by a young Spanish sculptor, with a focus on the ‘ginger’ hair of the emperor (ancient sources mention Nero’s hair to be either ginger or blonde). His project ‘Césares de Roma’ covers the facial reconstruction of three famous Roman personalities – Julius Caesar, Augustus Caesar, and Nero. Another distinct reconstruction, made by JudeMaris is presented below, and it showcases the blonde and rather plump side of Nero.

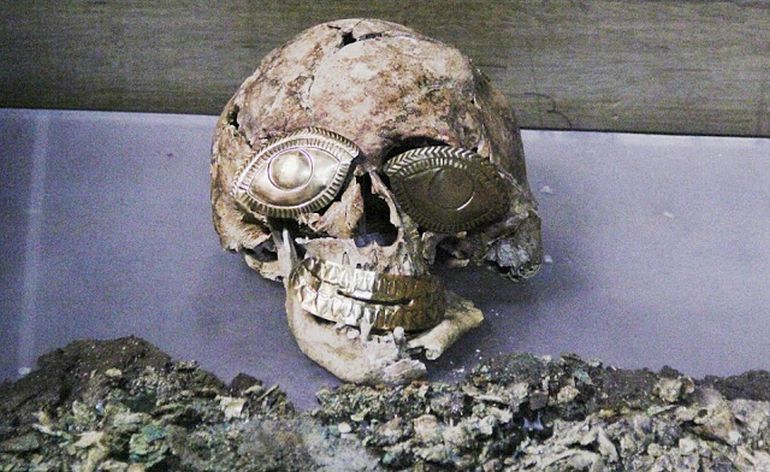

Lord of Sipan (circa 1st – 2nd century AD)

Often heralded as one of the significant archaeological finds of the 20th century, the Lord of Sipán was the first of the famous Moche mummies found (in 1987) at the site of Huaca Rajada, northern Peru. The almost 2,000-year-old mummy was accompanied by a plethora of treasures inside a tomb complex, thereby fueling the importance of the discovery. And researchers have now built upon the historicity of this fascinating figure, by digitally reconstructing how the ‘lord’ might have looked in real life.

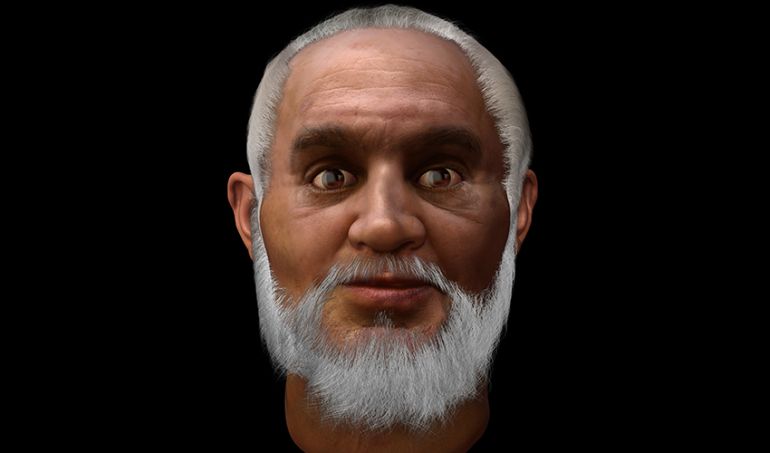

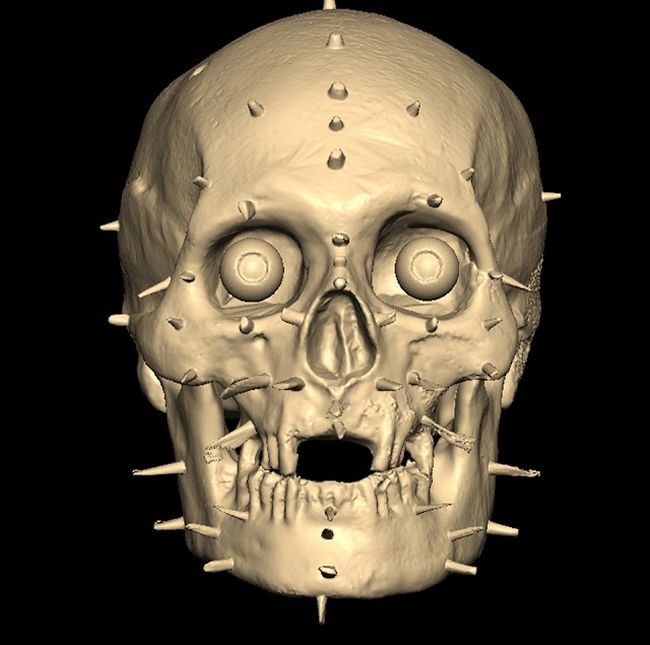

Of course, this was no easy feat, especially since the skull of the Lord of Sipán was actually broken into 96 fragments during the time of its discovery (due to the pressure of the soil sediments over the millenniums).

So as a result, the researchers from the Brazilian Team of Forensic Anthropology and Forensic Odontology had to painstakingly arrange together these numerous pieces in a virtual manner. The reassembled skull was then photographed from various angles (with a technique known as photogrammetry) for precise digital mapping of the organic object.

St. Nicholas (circa 270 – 343 AD)

From the historical perspective, there is no denying that the primary basis for Santa Claus was derived from the figure of St. Nicholas, a 4th-century Christian saint of Greek origin, who was the Bishop of Myra, in Asia Minor (present-day Demre in Turkey). Suffice it to say, like his jolly (though somewhat commercialized) counterpart, St. Nicholas or Nikolaos of Myra was also known for numerous deeds, with many of them being even considered ‘miraculous’.

Indeed he was known as Nikolaos the Wonderworker (Νικόλαος ὁ Θαυματουργός), and thus his reputation and legacy were preserved by many an early Christian saint, thus ultimately aiding in the characterization of latter-day Santa.

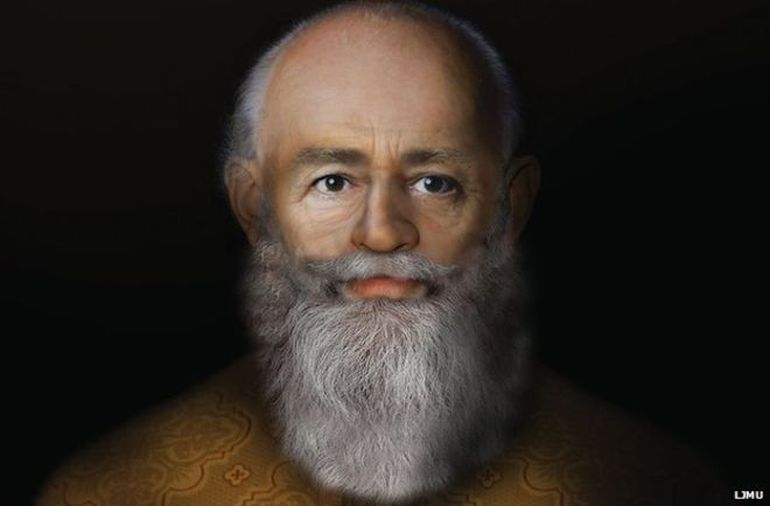

As for the recreation, aided by software simulation and 3D interactive technology by Liverpool John Moores University’s Face Lab, the above-pictured 3D model, was the result of detailed analysis – though it is still subject to various interpretations. According to renowned facial anthropologist, Caroline Wilkinson, the project was based on “all the skeletal and historical material”.

Interestingly enough, back in 2004, researchers made another reconstruction effort, based on the study of St. Nicholas’ skull in detail from a series of X-ray photographs and measurements that were originally compiled in 1950. And we can comprehend from this image, St. Nicholas was possibly an olive-toned man past his prime years, but still maintaining an affable glow that is strikingly similar to the much later depicted Santa.

His broken nose may have been the effect of the persecution of Christians under Diocletian’s rule during Nicholas’ early life. And interestingly enough, this facial scope is also pretty similar to the depictions of the saint in medieval Eastern Orthodox murals.

Robert the Bruce (1274 – 1329 AD)

An incredible collaborative effort from the historians from the University of Glasgow and craniofacial experts from Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) resulted in what might be the credible reconstruction of Robert’s actual face.

The consequent image in question (derived from the cast of a human skull held by the Hunterian Museum) presents a male subject in his prime with heavy-set, robust characteristics, complemented aptly by a muscular neck and a rather stocky frame. In essence, the impressive physique of Robert the Bruce alludes to a protein-rich diet, which would have made him ‘conducive’ to the rigors of brutal medieval fighting and riding.

Now historicity does support such a perspective, with Robert the Bruce (Medieval Gaelic: Roibert a Briuis) often being counted among the great warrior-leaders of his generation, who successfully led Scotland during the First War of Scottish Independence against England, culminating in the pivotal Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 AD and later invasion of northern England.

In fact, Robert was already crowned as the King of Scots in 1306 AD, after which he was engaged in a series of guerrilla warfare against the English crown, thus illustrating the need for physical capacity for the throne contenders in medieval times.

Reverting to the reconstruction in question, the ambit of physical strength was ironically also accompanied by frailty, with the skull analysis showing probable signs of leprosy which would have disfigured parts of the face, like the upper jaw and the nose.

Once again bringing history into the mix, scholars have long hypothesized that Robert suffered some ailment (possibly leprosy) that significantly affected the Scottish king’s health in the latter stages of his life. During one particular incident in 1327 AD, it is said that the king was so weak that he could barely move his tongue in Ulster; and only two years later Robert met his demise at the age of 54.

However, as with most historical reconstructions, the experts have admitted that the recreated scope has some percentage of imbued hypothetical data – especially when it comes to the color of Robert’s eyes and hair. As Professor Wilkinson herself stated –

Using the skull cast, we could accurately establish the muscle formation from the positions of the skull bones to determine the shape and structure of the face. But what the reconstruction cannot show is the color of his eyes, his skin tones, and the color of his hair. We produced two versions – one without leprosy and one with a mild representation of leprosy. He may have had leprosy, but if he did it is likely that it did not manifest strongly on his face, as this is not documented.

Now, these facial factors could be established by using the original DNA of the individual. But in the case of the Hunterian skull, the object is just one of the very few casts of the actual head of Robert (pictured above).

In that regard, the original skull was excavated way back in 1818-19 from a grave in Dunfermline Abbey but was later sealed and reburied (after some casts were made). However, in spite of the ‘drawback’, the researchers tried their best at recreating the presumably authentic features of the medieval Scottish warrior-king.

Richard III (1452 – 1485 AD)

The last king of the House of York and also the last of the Plantagenet dynasty, Richard III’s demise at the climactic Battle of Bosworth Field usually marks the end of the “Middle Ages” in England. And yet, even after his death, the young English monarch had continued to baffle historians, with his remains eluding scholars and researchers for over five centuries.

And it was momentously in 2012 when the University of Leicester identified the skeleton inside a city council car park, which was the site of Greyfriars Priory Church (the final resting place of Richard III that was dissolved in 1538 AD). Coincidentally, the remains of the king were found almost directly underneath a roughly painted ‘R’ on the bitumen, which basically marked a reserved spot inside the car park since the 2000s.

As for the recreation part, it was once again Professor Caroline Wilkinson who was instrumental in completing a forensic facial reconstruction of Richard III based on the 3D mappings of the skull.

Interestingly enough, the reconstruction was ‘modified’ a bit in 2015 – with lighter eyes and hair (pictured above), following newer DNA-based evidence deduced by the University of Leicester. And additionally, research at the University of Leicester had also dealt with the presumed accent in which the English king would have talked during his lifetime.

Henry IV of France (1553 – 1610 AD)

Henry IV of France (or Henri IV), also sometimes known by his epithet ‘Good King Henry’, was a pivotal political figure in late 16th century France. Being the first French monarch from the House of Bourbon, Henry IV was also known for his Protestant inclinations (he considered himself a Huguenot in the initial years), which brought him at loggerheads with the Catholic royal army.

In fact, this clash later translated into a full-fledged military conflict known as the Wars of Religion, which in spite of its name, was not just determined by religious affiliations but also political motivations.

Given such a chaotic scope strewn with military, religious, and political upheavals in 16th century France, it does come as a surprise that Henry IV of France is also known as ‘Good King Henry’ (le bon roi Henri).

The moniker possibly comes from his perceived geniality and thought of welfare for his subjects, in spite of their initial religious differences. Impressed by such ideals of enlightenment in the late medieval period, researchers headed by the famed facial reconstruction specialist Philippe Froesch have successfully recreated the face of the French monarch with state-of-the-art visual techniques.

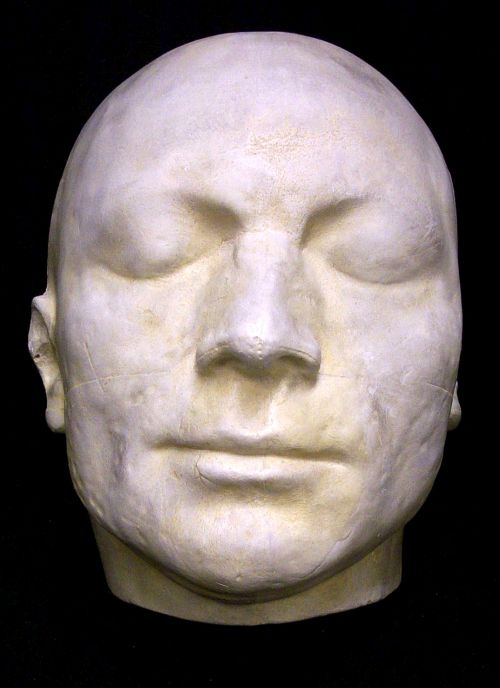

Maximilien de Robespierre (1758 – 1794 AD)

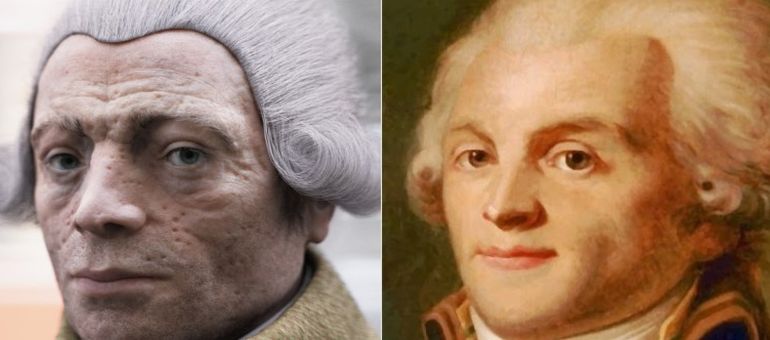

Back in 2013, forensic pathologist Philippe Charlier and facial reconstruction specialist Philippe Froesch (who also participated in the recreation of Henry IV) created what they termed as a realistic 3D facial reconstruction of Maximilien de Robespierre, the infamous ‘poster boy’ of the French Revolution. But as one can gather from the actual outcome of their reconstruction, contemporary portraits of Robespierre were possibly flattering to the leader.

Originally published as one of the letters in the Lancet medical journal, the reconstruction was made with the aid of various sources. Some of them pertain to the contemporary portraits and accounts of Robespierre, in spite of their ‘compliant’ visualization of the revolutionary.

But one of the primary objects that helped the researchers, pertain to the famous death mask of Robespierre, made by none other than Madame Tussaud. Interestingly enough, Tussaud (possibly) claimed that the death mask was directly made with the help of Robespierre’s decapitated head after he was guillotined on July 28th, 1794.

Be the first to comment on "Visual Reconstruction Of 12 Well-Known Historical Figures"