Introduction to the Roman Houses and Villas

From the historical perspective, the Roman domus (house) was oddly enough not exactly ‘Roman’ in its character. Rather it was possibly inspired by a few older Mediterranean cultures including the Etruscans and the Greeks – as is evident with the architectural focus on the central courtyard. Now beyond origins and influences, a typical Roman house not only served as a dwelling for the Roman familia, but was also used as a ‘personalized’ center for business and religious worship.

As can be deduced from these functions, the extensive domus were constructed for the higher middle-class Roman citizens. And even then there were no standardized forms of the ancient dwelling type (although on average, there were probably 8 houses per city block). And in some cases, such ‘higher-end’ houses are often categorized as Roman villas, serving the upper class and the well-to-do of Roman society.

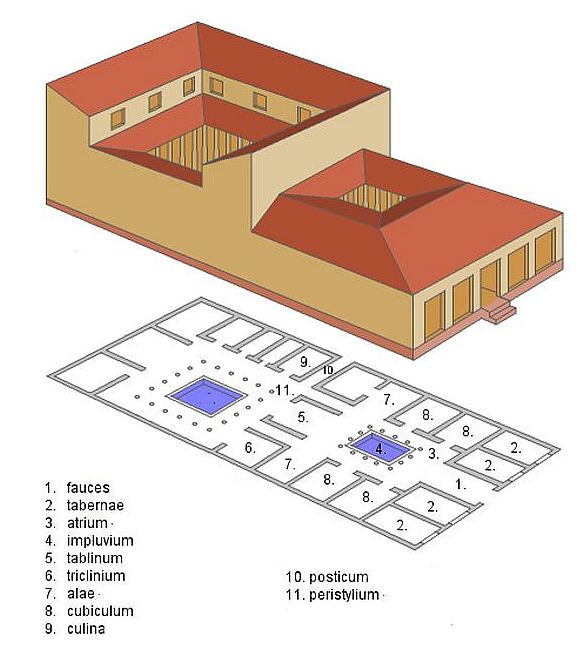

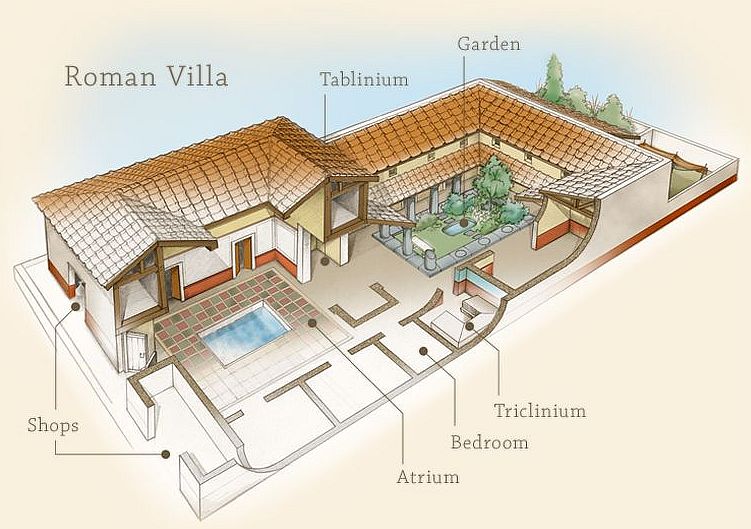

Visual Reconstruction of the Roman House

In any case, the resourceful folks over at Ancient Vine and Museum Victoria have given a go at virtually reconstructing the typical Roman domus of a ‘well-to-do’ family – and we daresay they have succeeded in portraying the dynamic internal layout of the Roman ‘domestic’ side of affairs.

The Roman Villa Layout –

The Atrium –

The video starts off with what is known as the atrium section of the Roman domus. This central hall was the focal point of the entire house and was accessed from the fauces (a narrow passageway connecting to the streets) or the vestibulum. Now like its modern-day counterpart of a living room, the atrium was the semi ‘public’ area (pars urbana) that was primarily used for entertaining the guests – and thus it was typically the most decorated section of the entire domestic scope.

Now intriguingly enough, the animation showcases a rather curious opening through the ceiling, which was actually called the compluvium. Used primarily for ventilation purposes, this conspicuous aperture also allowed the entry of rainwater, which was then collected on the floor-based cavity known as the impluvium and then passed on to the underground cisterns for household usage.

The video continues by showcasing the rooms that were attached to this central hall of the atrium. Most of these enclosed spaces comprised the cubicula, which were basically chambers of the house (a few being also located on an upper floor); and they were accompanied by the lararium (household shrine at one corner), slave/servant quarters, and latrines of the house.

These rooms were often flanked by the alae (side rooms), which further led to the triclinium (dining room) at the corner of the atrium. Now the dining room was considered a privileged place by the ancient Romans. Triclinium in itself roughly translates to ‘three couch place’ because the guests treated here (with lavish dinner parties) often ate and drank their sumptuous fares by lying on their sides on the couches that were arranged in a U-shaped fashion.

The last room of the atrium that ultimately connected with the peristylium (the rear open-air courtyard) usually consisted of the tablinum or ‘office’ of the paterfamilias – the male head of the household. The video aptly depicts this section as the official spatial zone with the low table that stored all the important documents and business dealings.

Now oddly enough, if we look closely, the atrium of the Roman domus didn’t seem to have any window openings that faced the streets. This was probably because safety was still a primary concern of the well-to-do citizens of ancient Rome, even when the city (and the empire) was at the apical stage.

The Peristylium –

As we mentioned before, the peristylium was the open-air courtyard behind the atrium, and it was usually colonnaded along its square (or rectangular) perimeter. Mainly used as a recreational zone for the children to play and for the family and guests to walk around, the peristylium combined the attributes of a garden and a courtyard, while sometimes also flaunting its central fountains.

In some cases, this open-air colonnaded courtyard was flanked by cubicula (bedrooms) and a triclinium – the aforementioned dining room from where the guests could pleasurably view the inner garden while feasting.

The peristylium was also connected to the culina (kitchen) and other storerooms. And finally, this courtyard was flanked on its rear side by a curious arrangement known as exedra. The exedra was basically a large and often decorated room with elaborate mosaic floors.

This space also carried forth the thematic element of a garden with its unique wall paintings and frescoes. Some Rome domus additionally boasted the hortus (garden) – the actual garden that was situated at the rear-most part of the entire house compound.

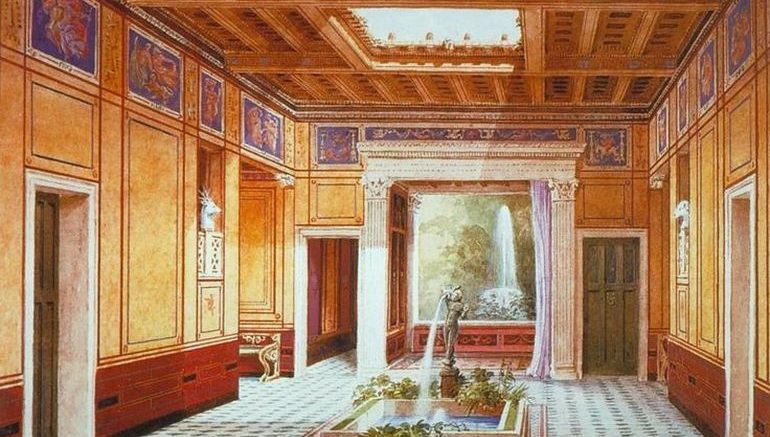

Reconstruction of the Roman Domus –

The Upper-Class House of Caecilius Iucundus –

Envisaged as a continuation of the Swedish Pompeii Project (now overseen by Sweden’s Lund University), the reconstruction project was led by archaeologists Anne-Marie Leander Touati – with the experts utilizing 3D scanning and even drone technologies.

The domus we see here belonged to one Caecilius Iucundus, a wealthy banker from Pompeii who lived almost 2,000 years ago. The house was located in the city block termed Insula V1, which was thoroughly analyzed by 3D scanning and drones (conducted during fieldwork expeditions between 2011 and 2012). The site itself was chosen because of its ‘prime’ location at the crossing of two of Pompeii’s main thoroughfares. Suffice it to say, the neighborhood with its easy access to the city’s commercial facilities translates to the affluence of Iucundus and the opulence of his house.

Now while we fleetingly mentioned the authentic scope of this reconstruction, the accuracy of the project is confirmed when it comes to the decorative elements, given their preserved nature in Pompeii as evidenced by archaeological surveys. On the other hand, the actual architecture of the domus is obviously based on speculative factors, though bolstered by the known style and arrangements of spatial elements used during Roman times.

Interestingly enough, in spite of his affluence, Iucundus was not actually a member of the ruling political elite of Pompeii. And in addition to his domus, the Insula V1 block also boasted two additional estates of wealthy patrons, accompanied by a tavern, bakery, laundry, and gardens (one of which had its taps running for the fountain during the eruption of Vesuvius).

And, in case one is interested, below is a sneak peek at how the researchers arrived at their ‘reconstructed’ conclusion. To that end, the team is looking forth to compile an entire 3D data set and workflow that would be made accessible to other researchers and students, for a more concerted effort on future projects involving the grandeur of Pompeii.

The Dionysiac Villa –

Tradition has it that the so-called ‘Villa of Augustus’, also known as the Dionysiac Villa in Somma Vesuviana, near Nola (an ancient Campanian town in Naples) was the place where Emperor Augustus breathed his last, circa 14 AD. Now while from the scholarly perspective, this claim is debatable, there is no doubt about the archaeological eminence of the site.

Pertaining to the latter, Altair4 Multimedia has virtually reconstructed the Villa of Augustus, based on the extant remnants of the substantially large structure. And the end result is glorious to behold, standing as a testament to ancient Roman art and architecture.

Now interestingly enough, a recent discovery has rather reinforced the architectural ambit of the Dionysiac Villa. To that end, researchers as part of a collaborative effort from Benincasa University in Naples and the University of Tokyo, have found a massive cistern within the complex that boasts almost 300 sq m (or 3,200 sq ft) of area, with its impressive 30 m length and 10 m width.

According to archaeologist Antonio De Simone, the cistern structure covered by dual walkways was built to salvage water from the nearby mountains. The collected water, in turn, was also used to supply the proximate farmland. Quite intriguingly, in spite of the mystery of its ownership, the villa in itself was spared from the wrath of Vesuvius’ eruption in 79 AD (though there are samples of volcanic deposits within the complex). As a result, the villa was possibly being continuously used as a large farmhouse (aided by the functioning cistern), until it was finally destroyed by the baleful eruption of Vesuvius in 472 AD.

Lastly, the Dionysiac Villa in Somma Vesuviana was so named because of its ‘stash’ of various intricately crafted statues, including one that depicts a young Dionysus with a panther. These sculptural feats are complemented by a flurry of frescoes, like the famed ‘Nereids and Tritons‘. And given the huge dimensions of the domus, along with its founding date reverting to circa 1st century AD, has led to the conjecture that this villa was the very same one referred to by Tacitus as ‘apud urbem Nolam’ in his Annales.

First Video Credit:AncientVine (YouTube)

Other Sources (for the article):KhanAcademy / AncientEncyclopedia / VRoma

Be the first to comment on "The Roman Domus (House): Architecture and Reconstruction"