Introduction

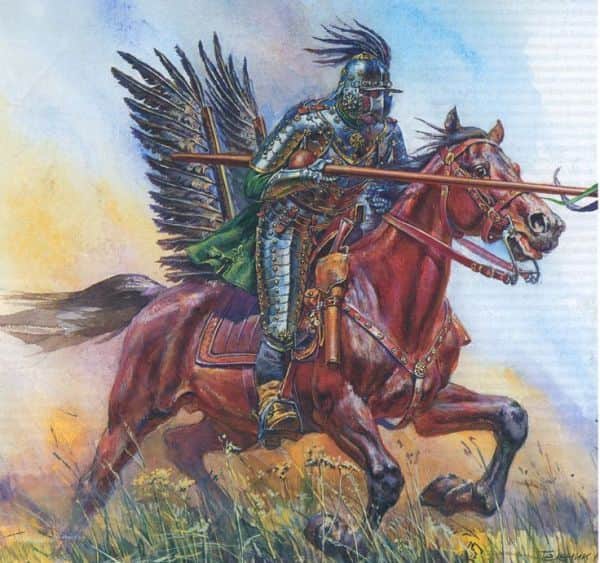

The Polish Winged Hussars epitomized the shock cavalry arm of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth between the 16th and 18th centuries. Showcasing their stylized yet heavily armored ensembles, partly fueled by the late-16th-century reforms of Stephen Bathory (one of the most successful kings in Polish history), the winged hussars serving under their dedicated banners (chorągiew) were essentially the elite of the (often victorious) armies of the thriving Eastern European commonwealth.

Known for their decisive impact on numerous military encounters, like the Battle of Lubieszów (1577 AD), Battle of Pitschen (1588 AD), Battle of Kircholm (1605 AD), Battle of Klushino (1610 AD), and the Battle of Vienna (1683 AD) – which possibly entailed the largest cavalry charge in the history of warfare, the Polish Winged Hussars are rightly held in high regard by military historians and aficionados.

However, at the same time, many of their achievements and visual aspects have taken the route of romanticism (and embellishment), especially fueled by the non-contemporary chroniclers of the 19th century. So without further ado, beyond misconceptions and exaggerations, let us take a gander at the military history of one of the most successful and spectacular cavalry troops of all time – the Polish Winged Hussars.

Contents

- Introduction

- The Eastern Roman Origin?

- The Early Hussars of Poland

- The System of Company and Companions

- The Social Aspect of the Hussar Members

- The Retainers – Backbone of the Polish Winged Hussars

- The ‘Inflated’ Mode of Mustering

- The Different Avenues of ‘Payments’

- The Armor of the Polish Winged Hussars

- The Weapons of the Polish Hussars

- The Famed Wings and Other Apparels

- The Charge of the Polish Winged Hussars

- The Other Battlefield Roles

- The ‘Daredevils’

- The Predicament Posed by Firearms

- Honorable Mention – The Battle of Hodów

The Eastern Roman Origin?

While popular notions tend to pinpoint the origins of hussars in Hungary, according to historian Richard Brzezinski, the history of hussars possibly harks back to the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) times, circa the 10th century.

The Roman Empire recruited light cavalry from the Balkans (especially the Serbs), known as the chonsarioi (possibly derived from cursores, the Roman light cavalry). Many of the cavalrymen, known as gusars in Serbian, continued to operate in the region, even after the demise of the Eastern Roman Empire.

And while the majority of such gusars were perceived as unruly, brigand-like groups, they nevertheless did serve and protect Rascia, the medieval Serbian state that was ultimately conquered by the ascendant Ottoman Empire. Consequently, most of these unorganized yet militarily-effective regiments migrated to Hungary (to serve as the huszár or hussar) and Poland.

The Early Hussars of Poland

The Polish military of the early 16th century started to ‘regroup’ and furnish actual cavalry companies from the remnants of the Serbian gusars. Additionally, they also employed other nationalities like fellow Poles, Lithuanians, and Hungarians to bolster the hussar numbers (who were known as usar).

And while the original Serbian gusars preferred their light armor and asymmetrical Balkan shields (similar to the Albanian stradiots), the Polish usars adopted the heavy Hungarian style of armor and armaments, comprising mail shirts, helmets, shields, and lances.

By 1576 AD, the Polish hussars underwent a reform that standardized their equipment and armor, in line with Polish king Stephan Batory’s personal royal guard of hussars. This translated to the adoption of breastplate armor and longer lances along with the eschewing of shields.

In other words, these companies of cavalrymen, who bridged the gap between heavy lancers and mobile horsemen, formed the first of the famed Polish Winged Hussars that we tend to admire and glorify in the realm of military history. In essence, these elite lancers were equipped and trained to fight both the cavalry and infantry force of the enemy.

The System of Company and Companions

A company of troops was known as rota in 16th century Poland. Each rota of Polish hussars generally consisted of anywhere between 100 to 150 horsemen (the figures did touch 300 on rare occasions for the hetmans and incredibly wealthy nobles). These rotas were furnished and commanded by the rotmistrz (‘rota-master’), who usually hailed from the upper sections of nobility (or szlachta) of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Simply put, the wealthy rotmistrz was tasked with forming up his company of hussars on a contract basis that was stamped by the offices of the monarchy as a ‘letter of recruitment’. This essentially made the rota his extended bodyguard unit that could produce revenues via payments from the state along with war booty.

This naturally raises the question – how did these companies recruit the hussars? Well, most of these rotas comprised many smaller retinues (poczet) headed by the towarzysze (companion). Simply put, each company of lancers was composed of multiple retinues (which had two to six similarly armed retainers or pacholiks), and these smaller groups were assembled by their individual towarzysze.

These ‘hussar companions’ also came from the szlachta class of Polish nobility, albeit with lesser means than the rotmistrz – and they were tasked with providing manpower (with their retainers), sharing the economic burden of the company, and even performing duties of an officer at the camp and on the battlefield.

The Social Aspect of the Hussar Members

It should be noted that the Polish Hussars were indeed considered an elite group of mounted soldiers during their contemporary age. Essentially, these mounted companies were acknowledged as exalted institutions that merged martial prowess with stately panache and dedicated patriotism.

And thus, even while bearing the rank of a junior officer in such an exclusive group, the towarzysze (companion) rightly considered himself a member of an elite military fraternity that tended to overshadow other army divisions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Practically, the service of the Winged Hussar commanding officers (generally ranging from three to five years) translated to social advancements and opportunities for the towarzysze. To that end, a lower-ranking noble (with lesser economic means) could gain titles (like ‘soldier-knights’), endowments, and future civil careers from the monarchy.

In fact, there were also known cases of rich men from even non-noble backgrounds who purchased their way into the ranks of towarzysze, though such scenarios were pretty rare. On the other hand, the younger sons of the wealthier nobles also preferred the status of towarzysze because they were anyway less likely to inherit their familial properties.

The Retainers – Backbone of the Polish Winged Hussars

However, beyond the high-born nobles, wealthy magnates, and well-to-do officers, the core of the Polish Hussar companies was composed of regular horsemen or retainers (or pacholiks – ‘youths’). The majority of these troops came from a non-noble background, thus establishing the trend of lower classes opting for military careers in the Polish armies.

A few of these retainers also hailed from the aforementioned szlachta class, although of an impoverished nature. In other words, the military relationship between a towarzysze (companion) and his pacholiks (retainers) was somewhat akin to a knight and his squires if perceived through the lens of Western European analogy.

On the other hand, as historian Richard Brzezinski noted, if we insert an economic angle in the company of Polish Winged Hussars, the towarzysze certainly had more control over his retainers, since he directly owned the equipment and horses of his followers.

To that end, the pacholiks were often treated as nominal servants and even as slaves with irregular pay and unfair shares of war booty. By the late 17th century, decades after the heydays of the Polish Hussars, the pacholiks were simply called pocztowy (meaning ‘of the poczet‘ or retinue), thus etymologically snatching away the romanticism associated with the term ‘youths’.

The ‘Inflated’ Mode of Mustering

Like most contemporary military units of the time, the Polish troops of the Hussar companies, after their drafting, were officially presented before a commissioner who was tasked with registering their muster rolls. However, while on the official level, each company had 200 horsemen, these figures were rather inflated.

This was done by theoretically considering the strength of the retinue of the rotmistrz himself (that often went beyond 20 retainers on paper, but was non-existent in reality), along with some of the followers of higher-ranking towarzysze. Simply put, the actual strength of individual companies of hussars often stood at 164 to 180 mounted soldiers, as opposed to the standard 200 horsemen.

Now while this may seem to be an odd oversight on the part of the officials, the practice of ‘inflated’ manpower was adopted to suit and adjust the extra costs that were borne by the rotmistrz for running his company of Polish lancers.

In essence, the state-administered pay for the 20 to 30 extra horsemen (as laid down in the letter of recruitment) was directly taken by the commander to cover the expenses of his unit and officers, while also accounting for some profit out of his military venture.

In that regard, by the mid-17th century, the companies of Polish Winged Hussars rather mirrored commercial enterprises in which the rotmistrz (usually a wealthy magnate), although officially being the commander, only held an honorary post. This allowed him to ply his business far away from the frontlines. The hussars in actual battles were commanded by his subordinates and career soldiers, including cavalry officers of the towarzysze rank.

The Different Avenues of ‘Payments’

The Polish Hussars of the late 16th century received a salary of 15 zloty, with payments being made on a quarterly basis (thus amounting to 60 zloty per year) – the figures being sourced from the Polish Winged Hussar 1576-1775 (By Richard Brzezinski). This sum rose to 51 zloty by the mid-17th century, but remained constant till the early decades of the 18th century, in spite of inflations and currency crashes throughout the mercurial years.

The officers (of the towarzysze rank) and the commander (rotmistrz) of the companies were also paid additional state-sanctioned funds, including kuchenne (or ‘kitchen money’) that amounted to a substantial 150 zloty per quarter for 100 horsemen and the hiberna (or ‘winter allowance’) for sheltering and lodging during winters.

Such funds were sometimes taken forcibly from the host population and often contributed substantially to the revenues of a hussar company. Additionally, the state was also expected to pay for the hussar lancers’ numerous apparel, including the famed leopard skins and wings.

And of course, other than such official (and unofficial) payment methods, most hussars relied on the war booty. Furthermore, as we mentioned before, the officers of the towarzysze rank also looked forth to high-paying state offices after their serving period in the army. Some of them even held other military ranks (like colonelcy) in the Polish army that had salaried benefits in addition to their roles in the companies of hussars.

The Armor of the Polish Winged Hussars

We already talked about how Polish king Stephan Batory played an instrumental role in standardizing the armor and equipment of the hussars. Pertaining to the former, the predominant armor adopted by these winged horsemen from the late 16th century to the early 17th century (arguably their Golden Age) followed the style of the heavy Hungarian cavalry, which translated to the anima cuirass with its lobster-like arrangement of plates.

Later it was modified into a ‘half-lobster’ form after 1600 AD. However, by the 1630s, the armor of the hussars once again took a heavier route that was coupled with their ostentatious styles and oriental fashions (influenced by their Turkish foes). These cavalrymen also abandoned wooden shields in favor of the substantial heavy body armor.

And interestingly enough, the heavily armored hussars made themselves visually even more impressive by burnishing the layers, as opposed to the Western style of blackening the outer facades to prevent rust.

Batory’s Hussars were additionally known to wear mail sleeves and gauntlets, but both of these protective elements were relegated in favor of comprehensive arm guards by the last years of the 16oos. Moreover, it should be noted that it was only the towarzysze ranked ‘companions’ and their chosen retainers who often flaunted their heavier, well-crafted hussar armor with better finishes. This type of heavy armor was mostly worn over a specially padded coat for better comfort.

On the other hand, the pacholiks who served in the rear ranks of a hussar company were only given cheaper versions of the classier sets. By the later years of the 17th century, even such protective measures were taken away, with the ordinary retainer (pocztowy) only donning his standard low-cost helmet and eastern long coat without any metal cuirass.

The Weapons of the Polish Hussars

The definitive weapon associated with the winged horsemen arguably relates to the hussar’s lance, more specifically the kopia lance. Usually made of cheap pine or fir wood, the kopia was crafted for single-use purposes, and as such was designed with a hollowed shaft that made the weapon particularly light in its bearing.

According to contemporary sources, most kopia Polish lances measured somewhere between 13 to 19 ft. They were possibly crafted by combining longitudinal, hollowed-out segments of the wood that were packed with sinews, glue, and silk threads – thus resulting in a composite yet lightweight shaft (that was sometimes richly gilded).

The kopia lances also had the distinguishing feature of the spherical handguards that were known as galka (‘knob’) in Polish (though foreigners described them as ‘apple-shaped’).

As for their secondary weapons, the Polish Winged Hussars carried the saber (szabla), with the koncerz style sword being uniquely associated with these mounted companies. Designed as a stabbing weapon, the koncerz tended to have a thin square or triangular cross-section with a sharp pointed end (more akin to a spear point), which made it effective in piercing armor but inadequate for slashing.

The heavy cavalry was also known to wield other varieties of swords, including the pallash (broadsword with saber-type hilt) and the karabela (distinguished by its bird’s head-shaped pommel).

Quite intriguingly, the Polish hussars (circa 16th century) were also known to carry bows to the battlefield, with the anachronistic bow possibly perceived as a mark of honor (as opposed to a handy weapon) for the towarzysze cavalry officers of the National Army. However, by the latter half of the century, many of the companies grudgingly took up firearms – as dictated by the practicality of the ever-evolving battlefield tactics.

By 1576 AD, Stephan Batory further standardized the adoption of wheellock pistols for most cavalrymen of the Polish Winged Hussars. This tradition was rather expanded upon in the 17th century when some of the hussars even carried two pistols equipped with efficient French flintlocks.

The Famed Wings and Other Apparels

Probably the most controversial aspect of the Polish Winged Hussars in military history relates to their wings. In essence, while the feathered elements defined the ‘winged’ visual flair of the hussars, historians, and academics are still not sure as to how and why these wings were worn.

Contemporary writers also gave confusing accounts of the wings, with one dating from circa 1674 AD mentioning how the hussars (still not standardized in their equipment) decorated themselves and their horses with gold-striped eagle feathers. After Batory’s reforms – wherein the king explicitly mentioned wings being a part of the hussar uniform, the horsemen possibly inserted the simply-framed feathered wings (in pairs) at the back of their saddles.

This style of incorporating a pair of feathered wings into the saddle possibly continued till the mid-17th century. But then again, it naturally raises the question – what about the popular imagery of Polish Winged Hussars charging into battles with the feathered adornments worn on their own backs (instead of the saddles)?

Well, this may have been the case in the latter part of the 17th century, especially during the reign of John Sobieski. For example, 18th-century Polish historian Jędrzej Kitowicz talked about how the Polish hussars wore their multi-colored bristling feathers sticking to the armor via wooden segments. On the other hand, Kitowicz also mentioned how their Lithuanian counterparts still preferred the ‘old’ style of saddle-connected wings.

In any case, beyond the scope of ‘how’, scholars still debate the actual functionality of these wings. To that end, it is a possible misconception that the wings were worn due to the ominous sound effects emanated during the course of a hussar charge. In fact, the very notion of the hussar wings producing shrill sounds during battles can be ascribed to foreign authors who did their part in romanticizing it.

This brings us to another (and arguably more credible) possibility that the wings were mostly worn by the hussars during parades and special occasions. It should also be noted that the style of horsemen with decorative wings was not indigenous to the Polish cavalry. They were preceded by the deli (meaning ‘reckless’ or ‘crazy’) horsemen recruited from the Balkans by the Ottoman Empire.

To that end, many historians are of the opinion that these wings, as opposed to auditory purposes, were used for their fashionable (and perhaps intimidating) flair that expressed the high status enjoyed by the companies of the Polish Winged Hussars. So when the feathered wings were accompanied by their leopardskin-draped attires, burnished armor, and lances with fluttering pennants, the overall visual impact must have been a fascinating sight to behold.

But of course, pertaining to the leopardskins, many of these seemingly ostentatious capes were sourced from smaller feline species like lynxes, with the pelts being sewn together. However, on rare occasions, many a rich towarzysze flaunted his exotic pelt underneath the saddle or tied around his hips – sourced from predators such as snow leopards, wolfs, and even brown bears.

The Charge of the Polish Winged Hussars

As opposed to the ‘tight-packed’ charge of the medieval European knights (who kept conrois formations), the heavily armored hussars fought in relatively loose formations that allowed them to be more mobile and reactive on the battlefield.

Such dynamic maneuvers often allowed for sudden changes in directions and overlapping movements. When translated to a figure, each hussar possibly had a space of 6 ft length for tactical maneuvering.

Now beyond agile movements, the Polish Winged Hussars were known for their headlong charges that harked back to medieval-style lancers. This was seemingly an anachronistic mode of engaging the enemy in the 16th-17th centuries, but nevertheless pretty effective when it came to deciding battle results by breaking infantry units.

To that end, in a typical charging maneuver, it should be assumed that the hussars first tightened their formations. This is in contradiction to the myth of these lancers being able to change their formations during charging.

Once grouped together (or tighter), the formation gradually gathered pace to create momentum before clashing with the enemy lines. Interestingly enough, there is a possibility that, unlike Western lancers, the Polish Winged Hussars kept their lances by their supports (known as tok) even during the point of impact.

In any case, since we brought up the scope of the impact of a cavalry charge, the subject is still a matter of debate. To that end, while there is no denying the sheer momentum a heavily armed cavalryman (like a hussar) can bring to the fore when charging into the masses of infantrymen, there are other factors of practicality to consider.

One of these particular factors directly pertains to the ‘lighter’ kopia lances that were specifically designed to shatter at impact. Simply put, the kopia lance may not have been the deadly ‘impaling’ weapon against a heavy plate armored opponent, though such weapons were incredibly effective when the Polish lancers faced the lighter infantrymen and cavalrymen fielded by the Ottomans and Russians.

In essence, much like their medieval knightly counterparts, the hussars charged not to completely demolish the opponent’s infantry but rather to psychologically afflict and dismantle (‘crack open’) the enemy formations.

And when such a tactical task was accomplished, it was followed by the combined-arms method of the contemporary period that allowed the allied troops (ranging from other hussar companies, light cavalry like pancerny-kozak to haiduk infantrymen) to offer support and gain the initiative on the battlefield.

The Other Battlefield Roles

In practice, every company of Polish Winged Hussars was responsible for its own foraging, usually carried out by the servants and camp followers. However, on occasions, some pacholiks (sometimes even with a few commanding officers of the towarzysze rank) were tasked with both scouting and aggressive foraging. Essentially these hussar detachments acted as organized raiding parties that traveled light and made forays into enemy frontier settlements and baggage trains.

And when it came to siege battles, the heavy hussars represented the elite cavalry arm of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. So they were expected to provide protection to the frontlines (by making sorties and absorbing enemy fire) while the allied infantrymen dug their defensive trenches.

During rare situations, when the encounters turned into siege stalemates, the Polish lancers were known to courageously storm into the enemy positions. And on even rarer occasions, they dismounted and led assaults in pitched battles that resembled siege scenarios with field works, wooden obstacles, and wagon fortresses.

Unfortunately, while these actions may seem to allude to the ‘flexibility’ of these elite cavalrymen as an all-scenario combat unit, in most siege battles they were kept in reserve for practical tactics (as opposed to bravado befitting their romanticized status).

Simply put, the Polish Winged Hussars were too expensive (to train, outfit, and equip) to be expended in cramped and brutal melee fighting situations interspersed with devastating volleys of firearms.

On the other hand, they truly shone in the decisive moments of the various pitched battles fought from the 16th to 17th centuries. This can be noted from the success of the Hussar formation against a range of foes like the Swedes, Russians, and Turkish forces.

The ‘Daredevils’

Befitting their demeanor of courageousness against odds and daredevilry, as Brzezinski noted, the Polish Winged Hussars also formed crack units from their different companies who were simply tasked with harassing the enemy before the real engagement.

Known as the elears, these seemingly reckless horsemen (usually numbering 100, consisting of four horsemen drawn from each company) advanced well ahead of the main army to engage the enemy with the means of various tactics, ranging from sacrificial charges, skirmishing to even throwing insults towards the foe.

Interestingly enough, while over time the impact of the daredevil elears diminished in the face of crippling firearms volleys, they did in many ways epitomize the esprit de corps of the Polish Winged Hussars. So even while in the later years of the 17th century, the role of the elears was taken over by lowly pacholiks and even ‘servants’, they always made use of the hussar lances and wings, possibly to intimidate and disorient the enemy frontlines.

The Predicament Posed by Firearms

In their element, the Polish Winged Hussars were one of the most effective and finest military units of the period encompassing the years from the late 16oos to the early 17oos. And while some of their feats were embellished and exaggerated by contemporary writers, these elite lancers, without a doubt, fought and emerged victorious against a wide variety of enemies – a list that even included pikemen.

Now pertaining to the latter, it should be noted that most of these pikemen engagements were won with the help of other allied troops; and the exception was the Battle of Kircholm (circa 1605 AD), where the battle was decided in just 20 minutes by the devastating charge of the Lithuanian hussars.

However, as we fleetingly mentioned in the earlier entry, as opposed to pikemen (who could be dealt with combined tactics), the bane of the Polish Winged Hussars proved to be the infantry firearms adopted by the enemies, especially the reformed Swedish armies instituted by Gustavus Adolphus and his successors.

By the third decade of the 1700s, the once glorious charging maneuvers of the hussar companies were sometimes perceived as suicidal tactics. That is because the battlefields of the era resembled sectors with mini-fortifications composed of wagons and wooden obstacles that were manned by determined infantrymen with firearms.

And by the second half of the very century, concentrated and focused volleys from muskets coupled with intersecting firing arcs from improved artillery created brutal ‘killing fields’ that simply made most cavalry charges anachronistic in military doctrines of the European armies.

Consequently, the Polish Winged Hussar regiments were relegated to only ceremonial duties by the 18th century – so much so that many of them were given the unflattering nickname of ‘funeral soldiers’. And finally, with the continuing slump of Poland’s economy during the period, the Polish parliament finally abolished the elite fighting unit of winged horsemen in 1776.

Honorable Mention – The Battle of Hodów

While there are mentions of various triumphs of the Polish Winged Hussars in encounters ranging from Kircholm to Vienna, popular history tends to miss the incredible episode of the Battle of Hodów – which can be dubbed as the Polish Thermopylae. Fought between over 10,000 Crimean Khanate irregulars and just 400 cavalry troops from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (comprising only 100 hussars), not much is known about the exact historical incident.

But it was possibly a large Tatar raid (or even invasion) into the Polish territory with the objective of capturing both loot and slaves. The local Polish administration responded to this surprise attack by calling upon the mounted hussars and pancerni forces from two regional strongholds in Red Ruthenia (present-day western Ukraine). Their initial action involved boldly charging headlong into 700-strong Crimean light cavalry, which resulted in the successful dispersion of the enemy forces.

However, the Polish commander (presumably a man named Konstanty Zahorowski) did notice the sheer numerical superiority of the Tatars, and so decided to withdraw to the nearby Hodów village – to set up a defensive perimeter with heavy and sturdy wooden fences. Inside this fortified ring, the Polish forces (especially the Hussars) made use of their long-range firearms and staved off relentless waves of enemy assaults for over six hours.

There are even accounts that suggest that the defending forces used improvised ammunition from ‘upcycled’ Tatar arrows. In any case, the heroic defense was successful, with over a thousand casualties on the Crimean Khanate side (who finally retreated to central Ukraine), and less than a hundred on the Polish side. Later on, the ‘skirmish’ incident was used as state propaganda by renowned personalities like King John Sobieski.

Book Reference: Polish Winged Hussar 1576-1775 (By Richard Brzezinski)

Online Sources: Polish Cultural Institute (link)

Featured Image: Illustration by Mariusz Kozik

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork, or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "Winged Hussars: The Mighty Shock Cavalry of the Commonwealth"