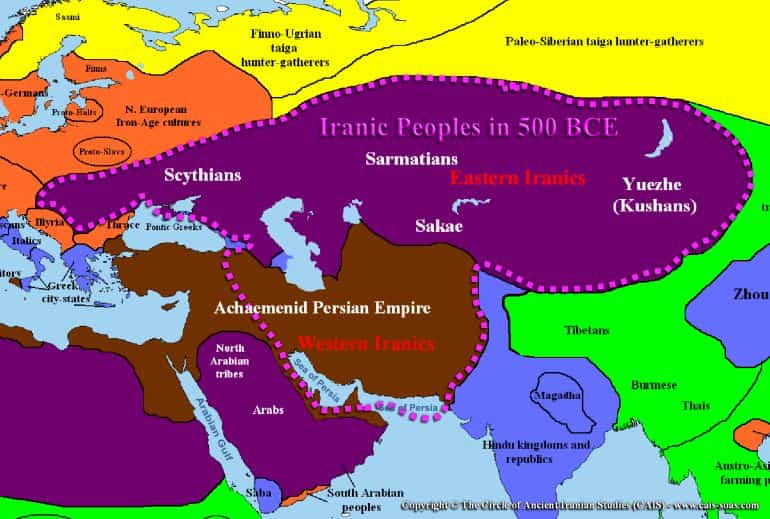

When it comes to the popular history of nomadic groups, tribes (and super-tribes) like Huns and Mongols have had their fair share of coverage in various mediums, ranging from literary sources to even movies. However, hundreds of years before the emergence of mixed-Huns, Turkic, and Mongolic groups, the Pontic steppe (and nearby Eurasian steppe) was dominated by an ancient Iranic (Indo-European) people of horse-riding nomadic pastoralists.

These ‘horse lords’ dwelled on a wide swathe of the landmass known as ancient Scythia since the 8th century BC. Epitomizing the very dynamic scope of the nomadic lifestyle – covering an impressive spectrum from workmanship to warfare, they were thus known as the Scythians, the master horsemen, and archers of the Iron Age.

Contents

- The ‘Giant Killers’ From Scythia

- The Scythian Tribes and Society

- The People’s Army of the Scythians

- Scythian Warriors – The Archers

- The Horsemen of the Steppe

- The ‘Fish Scale’ Armor of the Scythians

- The Amazons

- The Paradox of Craftsmanship and Warfare

- The Greek Connection in Armor

- Scythian Culture and Religion – The Penchant for Cannabis

- The Showdown With the Persians

- “Mouse, Frog, Bird and Five Arrows” – The Gifts of the Scythian Kings

- The Peak and Mysterious Decline of the Scythians

The ‘Giant Killers’ From Scythia

While the ‘Scythian Age’ only corresponded to the period from the 7th century to the 3rd century BC, the remarkable impression left behind by these warrior people was evident from the historic designation of (most of) Eurasian steppes as Scythia (or greater Scythia) even a thousand years after the rise and decline of the nomadic group.

Now a part of this legacy had to do with the incredible military campaigns conducted by the Scythians from the very beginning of their ‘brush’ with the global stage. According to Herodotus, they started off by defeating their nomadic brethren – the Cimmerians, and then dealt with the Iranian Medes; all before the 7th century BC

And by the 7th century BC, the emergent Scythians audaciously went into war with the sole superpower of the Mesopotamian region – the Assyrian Empire. Now while Assyrian sources mostly keep mum about some of the presumed Scythian victories over them, it is known that one particular Assyrian king Esarhaddon was so desperate to secure peace with these Eurasian nomads that he even offered his daughter, an Assyrian princess, in marriage to the Scythian king Partatua.

This, however, didn’t stop the Scythians from ravaging the coastal parts of the Middle East, until they reached Palestine and even the borders of Ancient Egypt. Consequently, they were bribed with rich tributes by the Pharaoh. And on their returning route, some remnants of the Scythian army allied with a Median force to finally lay siege to the Assyrian capital of Nineveh in 612 BC, thus paving the way for the downfall of Assyria.

As for the effect on the populace of the Middle East, a biblical prophet summed up the baleful nature of the ferocious ‘horse lords’ from the north (as referenced in The Scythians 700–300 BC by E.V. Cernenko) –

They are always courageous, and their quivers are like open grave. They will eat your harvest and bread, they will eat your sons and daughters, they will eat your sheep and oxen, they will eat your grapes and figs.

The Scythian Tribes and Society

Like most nomadic cultures, the Scythians were not a single homogenous tribe but were rather divided into tribal confederations. Even the origins of the Scythian people possibly covered a large geographical extent, ranging from Eurasia (Yamnaya culture), and the southern Urals, to western Siberia (Andronovo culture) and even East Asia.

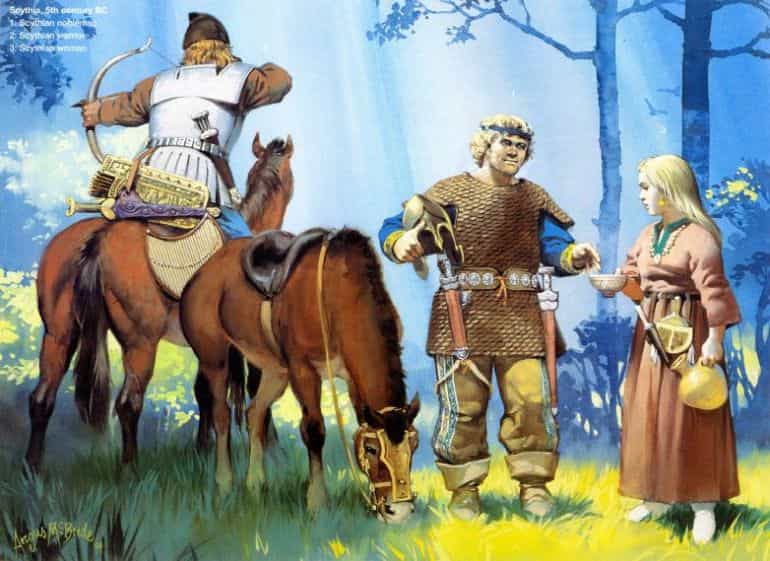

According to ancient writers like Herodotus, the numerous tribal groups of the Scythians could be condensed into three major tribes. One of them pertained to the so-called Royal Scythians, who were presumed to be the most powerful of the confederations because of their military strength.

As for the society of these steppe nomads, we have no evidence of a strict hierarchy that was found in other contemporary ancient cultures. However, there certainly were Scythian chieftains (some were referred to as kings) who headed the various tribal confederations. In that regard, while not comprising a politically centralized kingdom, the early Scythians presented a united front when it came to wars, defending against external threats, and even ritualistic celebrations.

Furthermore, archaeologists have also found evidence of urban or at least proto-urban Scythian settlements that suggests that at least a part of the population was sedentary in nature. These urbanized zones were probably the satellite areas under Scythian control – thus suggesting how the predominantly nomadic Scythians established trade, economic, and even political relations with neighboring realms (like the Greek colonies of the Black Sea).

The People’s Army of the Scythians

Oddly enough, while the socio-political effects of the Scythian incursions in the Middle East can be comprehended to some degree from contemporary (or near-contemporary) sources, historians are still mystified by the logistical and organizational capacity of the military of these nomads from the distant steppes.

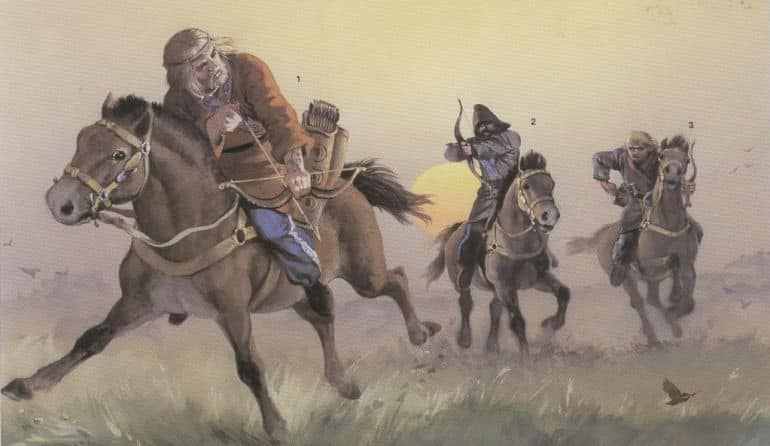

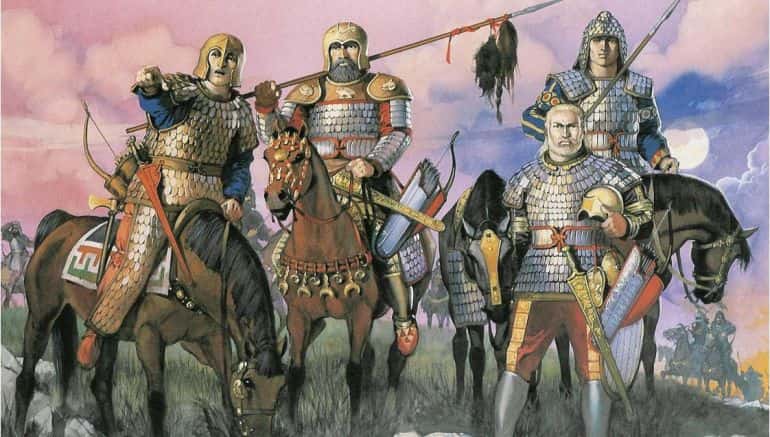

But it can be hypothesized that like most nomadic societies, the majority of the adult population was liable for military service (including some of the younger women). Now the tactical advantage of such a scope translated to how the bulk of the early Scythians had mounted warriors – mostly lightly armored with hide jackets and rudimentary headgear.

Carrying weapons such as arrows, javelins, and even darts, the hardiness, mobility, and unorthodox fighting methods espoused by these throngs of mounted archers seemingly countered the more ‘sedentary’ battle tactics of the wealthy Mesopotamian civilizations.

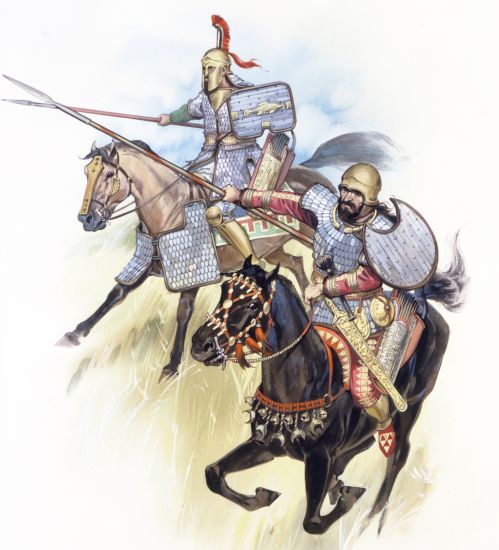

Furthermore, the light nomadic warriors were backed up by a core force of heavily-armored shock cavalry that was usually commanded by the local princes – and they took to the battlefield for the killing blow after the perplexed enemy was both ‘softened’ by the projectiles and harassed by zig-zag maneuvers.

Scythian Warriors – The Archers

According to some scholars (including Indo-Europeanist Oswald Szemerényi), the very etymological route of the term Scythian, and its other known ancient variants, like Assyrian Aškuz and Greek Skuthēs, is derived from *skeud-, an ancient Indo-European root meaning “propel, shoot”. Thus the restored Scythian name is *Skuda which basically entails an ‘archer’. So from this linguistic angle, we can pretty much sum up the importance of archery and bow in Scythian society.

The archaeological evidence from rich Scythian burial mounds also bolsters the theory of how the Scythian warrior was the master of archery, especially from horseback, much like many of the later armies emerging from the steppes of Central Asia and Europe.

Unfortunately, while archaeology has aided in preserving many of the arrowheads from such mounds, the design of the actual Scythian bow is lost to the rigors of time; and so has to be hypothesized from pictorial and literary pieces of evidence.

To that end, some written descriptions have mentioned how the composite Scythian bow might have resembled the Greek letter Σ (Sigma) in its recurved, unstrung form – and their sizes were probably a bit smaller than comparable specimens. As for the strings, the stretchy components were usually made out of horsehair or flexible yet sturdy animal tendons.

Most ancient authors concur on how the Scythian bow was heavy and extremely stiff, thus hinting at the substantial strength and deft skill needed to wield such weapons, especially from horseback. In fact, both extant and pictorial pieces of evidence suggest the penetrating power (and considerable range) of these bow varieties, with examples of skulls with still-embedded arrowheads and depictions of armored warriors being penetrated by arrows.

However, in spite of the tough nature of the powerful recurved bow, the expert Scythian mounted archers could match the firing rates of their Middle Eastern counterparts, with the capacity to unleash 10-12 arrows in a minute. Now considering that each archer carried around 30 to 150 arrows in a battle, the Scythians could entirely shoot out their potent projectiles within 15 minutes of the encounter.

Considering this tactical scope, one could only imagine the terror and affliction unleashed by ancient Scythian archery – with their hail of arrows and the troop of horses ‘tailored’ to crush the morale of most enemy forces.

The Horsemen of the Steppe

We fleetingly mentioned before how cavalry played a major role in the Scythian army. According to the 5th century BC Greek historian and general Thucydides, the Scythians could field armies numbering more than 150,000 if their tribes happened to have united. Now given the nature of the military state of the Scythians, this figure might not be overly exaggerated – and a significant part of the number may have comprised horsemen.

For example, as one could gather from Diodorus Siculus’ account of a late 4th century BC civil war in the Bosporan Kingdom (an ancient mercantile state that had both Greek and Scythian subjects), one of the armies, commanded by Satyrus, the true heir of the Bosporan throne, was composed of 10,000 horsemen and 20,000 infantrymen (from Greek, Scythian, and Thracian backgrounds). Their enemy forces, commanded by Aripharnes, had 22,000 horsemen accompanied by 20,000 on foot.

In a decisive engagement, it was once again the cavalry that determined the outcome of the battle, with Satyrus and his armored Scythian warrior retinue defeating the mounted regiments of Aripharnes and then smashing through the enemy ranks. The defeated forces then had to take refuge in a proximate fortress. Essentially, such historical episodes established the value of the Scythian horses and their riders in combat scenarios.

Furthermore, reverting to the figures, as Dr. Cernenko noted, no other army from the Classical age consisted of such high ratios of horsemen in their ranks. For example, even during Alexander’s era, the Macedonian army, known for its reliance on the renowned Companion heavy cavalry regiments, only had ratios of 1:6 when it came to cavalry and infantry. In contrast, the Scythians tended to have 1:2 ratios (or even 1:1 ratios on occasion), thereby underlining the penchant for horsemanship in the Eurasian steppes.

The ‘Fish Scale’ Armor of the Scythians

Many ancient armies used some variants of the corselet armor because of its general effectiveness against melee weapons. The Scythians were no exceptions, though they did modify some elements of the conventional corselet by arranging the metal (or leather) bits in a ‘fish scale’ like pattern.

These scales were usually arranged in a meticulous manner so that one metal bit could cover around one-third (or half) of the adjacent bit, thus resulting in an overlapping pattern. This overlapping technique was also repeated along the rows, thereby protecting the stitching and holes. And since we brought up stitching, these scales were affixed to a softer leather base with the help of animal tendons and leather strings.

Interestingly enough, as Dr. Cernenko mentioned, the Scythian preference for fish-scale armor was not just limited to corselets; they even crafted such scale-like protective layers upon their helmets, shields, and even fabric clothing. So while the fish scale armor was sturdy enough for most melee situations, one of the primary reasons for adopting this specific armor style was intrinsically related to the mobility it offered to the wearer.

In fact, from the historical perspective, other variants of the scale armor (like its lamellar counterpart) had survived for over a thousand years in various battlefield conditions around the world, thus attesting to its effectiveness and simplicity of use. Simply put, scale armor can be considered one of the major innovations in the history of military technology.

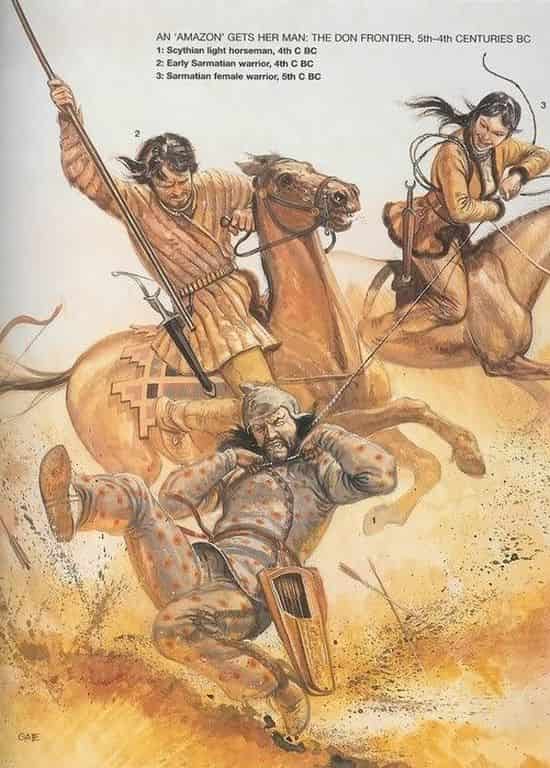

The Amazons

The so-called ‘Amazons’ pertain to the warrior-women generally associated with ancient Greek mythology. Now according to Herodotus, beyond sensationalized storytelling and mythology, these women were related to the Scythian groups and came from the geographical region of Sarmatia (present-day southern Ukraine and southern Russia).

And much to his credit, modern archaeologists have been able to unveil actual pieces of evidence that directly point to how women (or for that matter – warrior women) played a significant role in Scythian raids and conquests.

To that end, many researchers have taken advantage of DNA testing and other bio-archaeological scientific analysis to make a deeper analysis of the occupants of many Scythian burial mounds. To their surprise, the archaeologists found that around one-third of all Scythian women were buried with weapons.

As a matter of fact, not only were these deceased accompanied by knives and daggers but also bore marks of war injuries, much akin to their male counterparts. Simply put, such discoveries strongly suggest that there were groups of actual Scythian women who match the description of the ancient Amazons.

Unfortunately, these Scythian ‘Amazons’ got a bad rap from antiquity, with 5th century BC folk etymology (probably invented by the Greek historian Hellanikos) suggesting how the word Amazon roughly translated to ‘without breasts’, which alluded to the popular (though ill-informed) notion that these women cleaved off one of their breasts for better posture while shooting from the bow.

However, as we mentioned before, the very ‘manageable’ size of the smaller Scythian bow relates to a conceivable scenario where a woman could handle this primary weapon as well as her male counterpart, without requiring any anatomical ‘modification’. In that regard, the correct etymological origin of the word Amazon may have its roots in Old Persian *hama-zan meaning ‘all women’ or Iranian ethnonym *ha-mazan – ‘warriors‘.

The Paradox of Craftsmanship and Warfare

Beyond their savage ferocity, plundering tendencies, and acumen for sustained warfare (which Darius learned the hard way – discussed later in the post), the Scythians demonstrated their expertise in another field. And this ironically pertained to their penchant for creating fascinating specimens of gold-made artworks and artifacts.

To that end, as we mentioned before, much of the archaeological legacy of the nomadic Scythians comes from their large burial mounds (also known as kurgans), some of which rise over 20 m or 70 ft. Dotting the expansive scope of the Eurasian steppe belt, these mounds are found in disparate areas ranging from the Balkans, and southern Russia to Mongolia and even Siberia.

Suffice it to say, the tombs are still the largest source of Scythian gold artifacts – with the art styles of these objects being inspired by the neighboring cultures around Scythia. In other words, the influences are varied – with Greek, Urartian (ancient Armenian), Iranian, Indian, Chinese, and local nature of craftsmanship playing their crucial roles in developing the unique and intricate ‘Scythian art’.

In essence, the craftsmanship exhibited by the numerous Scythian gold artifacts may have been worked on by both Greek and indigenous artisans, while others were imported over a long distance from the Greek mainland. However, there is one element of the art style that stands out, and it relates to the predominance of zoomorphic symbology in the Scythian gold artifacts.

Simply put, Scythian art demonstrated by their gold objects, generally comprises a host of beast depictions – including stags, lions, panthers, horses, birds, and even mythical creatures (like griffins and sirens). These animals were often complemented by depictions of humans, including their faces, bodies, and sometimes groups of men – taking part in scenes like fighting, herding, taming horses, and even milking sheep.

Another thematic element that is often found in many such artifacts (discovered in the western Scythian lands) relates to the use of ancient Greek motifs (specifically from their mythology and history). This, in turn, is complemented by the Greek style of ornamentation and floral patterns. To that end, the Greek god Ares (or at least a similar deity) might have been a part of the Scythian pantheon – as Herodotus relates.

The Greek Connection in Armor

Beyond the scope of inspired workmanship, by the 5th century BC, many of the Scythian kings and nobles also opted for ‘foreign’ styled Greek helmets and greaves – possibly as a show of prosperity.

Archaeological excavations that pertain to this period have unearthed over 60 fascinating specimens of Greek helmets (of Corinthian, Chalcidian, and Attic types) that were actually manufactured in mainland Greece and then shipped across the Black Sea into the Scythian heartland via the wealthy Greek colonies of Bosporus.

The ancient scope in itself mirrored a wide-ranging trade network that not only entailed arms and military equipment but also slaves. Furthermore, the Scythians themselves exported profitable items like grain, wheat, flocks, and even cheese to Greece – via the northern Black Sea.

Scythian Culture and Religion – The Penchant for Cannabis

The Scythian proclivity for cannabis was nigh legendary – as attested by even ancient sources. Herodotus mentioned –

After the burial…they set up three poles leaning together to a point and cover them with woolen mats…They make a pit in the center beneath the poles and throw red-hot stones into it… they take the seed of the hemp and creeping under the mats they throw it on the red-hot stones, and being thrown, it smolders and sends forth so much steam that no Greek vapour-bath could surpass it. The Scythians howl in their joy at the vapor-bath.

Archaeological pieces of evidence rather support such ‘trippy’ scenarios, with one particular find pertaining to a burial of a warrior who had his head drilled – possibly to counter its swelling. He was accompanied by a cache of cannabis for good smoke even in his afterlife. And beyond just burial rituals, smoking pot was possibly a favorite pastime of the nobles within the Scythian society.

To that end, back in 2015, Russian researchers came across solid gold ‘bongs’ with exquisite craftsmanship (pictured above), inside a kurgan mound located in the Caucasus region. The experts additionally identified a black residue on the inner portion of one of the gold vessels. On further analysis of the substance (by criminologists), the results showed that the residues had been formed by not only cannabis but also opium.

Beyond the influence of psychoactive drugs on Scythian cultures and rituals, the Scythian religion incorporated what can be best termed as an archaic version of Indo-Iranian religions like Hinduism and Zoroastrianism (with later influence from Greek mythology via the Bosporan settlements).

To that end, according to Herodotus, the Scythian pantheon included deities like Tabiti – the goddess of hearth and heat, Api – the goddess of earth, Papaios – the god of heaven and sky, and Dargatavah – the ancestral god-king (son of heaven and earth).

As mentioned earlier, in the Scythian belief system, the god of war (Ares is the Greek equivalent) was accorded special status with specifically dedicated statues and altars. Few Scythian customs possibly demanded animal and even human sacrifices to be made in honor of this celestial war god.

The Showdown With the Persians

After more than a hundred years since the audacious Scythian raids and forays into the culturally rich regions of the ancient Middle East, it was the nomads’ turn to face the wrath of the sedentary armies from the ‘south’.

By the late 6th century BC, Darius I had already established the mighty Persian empire which was probably the largest superpower of the ancient world in terms of the controlled landmass – stretching from Anatolia and Egypt across western Asia to the borders of northern India and Central Asia.

And while Darius had always coveted the western lands of the Greek city-states, his strategic acumen convinced the ‘king of kings’ to secure the northern passages before a Greece-bound invasion. Thus the Scythian campaign was launched, and according to Herodotus, the Persian army numbered around 700,000 men. Now obviously, while this (improbable) figure must have been embellished, there is little doubt that the invading forces were one of the largest armies ever gathered in ancient times.

Interestingly enough, the Persian invasion possibly took the European route, by crossing the Hellespont and then overrunning the Thracian positions before the Danube River. They finally arrived at the Danube and successfully traversed the mighty river by anchoring ships across its banks. Hence the full-scale invasion began – pitting the sole superpower of the late 6th century BC against the boisterous nomadic ‘giant-killers’ of the ancient world.

“Mouse, Frog, Bird and Five Arrows” – The Gifts of the Scythian Kings

Unfortunately for the Persians, in spite of wide-ranging military reforms initiated by Darius, the bulk of their army comprised infantrymen. Now, according to Dr. Cernenko, considering the vast expanse of the Scythian steppes, this proved to be a logistical blunder, especially since the Persians had the unenviable task of supporting their high number of troops through unreliable supplies in an alien land across the Black Sea.

The situation of the opposing Scythians was not so easy either, with most of their allies refusing to militarily aid them – possibly because many of these fringe nomadic tribes were afraid of incurring the wrath of Darius.

Nevertheless, the Scythians (by this time, ruled by three kings with different hosts) decided to take advantage of the Persian logistical predicament, by employing hit-and-run tactics – conducive to equestrian warfare. So as the Persian forces slowly advanced through the Scythian heartland, they were not faced on open battlefields by the mobile enemy, but rather harassed in strategic locations and greeted with scorched lands and poisoned wells.

Consequently, the Persians began to run low on the essentials of food, water, and forage – and Darius was forced to stop his ponderous advance and set up a fortified camp by the northern flank of the Sea of Azov.

The desperate Persian emperor even sent out a messenger to the Scythian high ruler who asked him – why the Scythians were not offering any direct battle. In reply, King Idanthyrsus (one of the three Scythian kings) said, according to Herodotus –

This is my way, Persian. I never fear men or fly from them. I have not done so in times past, nor do I now fly from thee. There is nothing new or strange in what I do; I only follow my common mode of life in peaceful years. Now I will tell thee why I do not at once join battle with thee. We Scythians have neither towns nor cultivated lands, which might induce us, through fear of their being taken or ravaged, to be in a hurry to fight with you.

Ancient sources also mention how Idanthyrsus sent out some odd gifts to Darius, and they entailed – a mouse, a frog, a bird, and five arrows. And while the Persian emperor tried to convince himself of the good omens symbolized by these objects, one of his courtiers possibly interpreted the gifts in a more undiplomatic (although correct) manner. He said –

If you Persians do not fly away like the birds, or hide in the earth like mice, or leap into a lake like frogs, then you will never see your homes again, but will die under our arrows.

Consequently, the Scythians became more aggressive in their approach and started to make violent raids and forays into the confused Persian foraging parties. They even tried to cut off the potential Persian retreat points (albeit unsuccessfully) at the Danubian bridges. One particular episode also suggests that the nomads almost offered the Persians a pitched battle, although it was possibly a ruse that was set up to psychologically afflict the Persian king.

In any case, given his experience in conducting military affairs, Darius was acutely aware that his situation was becoming precarious with the passing of each day. So, in spite of being humiliated, he finally decided to make his orderly retreat back to the Danube, thus mirroring later-day failed campaigns like Napoleon’s invasion of Russia and Operation Barbarossa during WWII. As a result, the Scythians did manage to score a strategic victory over a superpower and continued to exert their influence in the proximate regions for almost three more centuries.

The Peak and Mysterious Decline of the Scythians

During the 5th century BC, after their strategic victory over the Achaemenid Persians, the Scythians went on the offensive and conducted military campaigns on their western frontiers, especially into Thracian lands. Circa 4th century BC, their high king, the 90-year-old Atheas (or Ateas) possibly matched the feats of Genghis Khan, by uniting many of the Scythian tribes, thus establishing a Proto-Scythian Empire.

However, one such campaign, commanded by Atheas, resulted in a disaster, with the leader and his entire army being annihilated by the Macedonians approaching from the south circa 339 BC. However, less than a decade later, the Scythians, in turn, decimated a 32,000-strong army of the Macedonians and their allies – who had audaciously tried to invade Scythia just like the Persians.

And while this period marked the apical stage (or Golden Age) of the Scythians, their aura of invincibility was snuffed out, if not shattered, by another nomadic group, the Sarmatians. Known as Sauromatae by the Greeks, the Sarmatians, composed of Iranic tribal confederations, and (possibly) ethnically related to the Scythians, made their crossings across the Don to raid and occupy Scythian lands.

At the nearly same time, the Greek colonies by the Black Sea broke the shackles of Scythian hegemony and began to reassert their independence from the horse lords. Gradually over a period of decades, the range of the Scythians decreased – due to pressure from their nomadic brethren and other mysterious reasons still unknown to historians.

Finally, the Scythians lost their hold over the Pontic Steppe by circa 3rd century BC, thereby leaving behind their legacy in the form of massive kurgans filled with weapons and artifacts, along with impressive gold objects boasting high-quality workmanship.

Book References: The Scythians 700–300 BC (By E.V. Cernenko) / The World of the Scythians (By Renate Rolle)

Online Sources: SmithsonianMag / Livius / Lost-Civilizations

Be the first to comment on "Scythians: The Ancient Horselords of the Eurasian Steppe"