Introduction

Often overshadowed by the exploits of the Ottomans in Europe and the Near East, it should be noted however that it was the Mamluks who, centuries earlier, were ultimately successful in defeating the European Crusaders in the Levant. But even more impressively, the Mamluks halted the Mongol charge into the Islamic world of the 13th century, by adopting both conventional and unconventional tactical measures.

And while they are often referred to as slave warriors and kings, their tradition carried forth the legacy of the Abbasid Caliphate and culminated into a separate class of warriors and chieftains that yet defied the prevalent nature of medieval rulership and hierarchy. So, without further ado, let us take a gander at the history of the Mamluks – the Islamic slave warriors who defiantly created their own dynasty in the regions of what is now Egypt and Syria.

*Note – In this article, we will focus on the Mamluks of Egypt, not other ‘slave dynasties’ that ruled over different parts of Asia.

Contents

- Introduction

- Origins of Mamluks and the Ghulam Connection

- The Mamluk System – Slave-Soldiers?

- Training and Skills of the Mamluks

- A Military Stratagem ‘Fueled’ by Mongols

- Armor and Weapons of Mamluks

- The Tactical Flair of the Mamluk Regiments

- The Sultan’s Mamluks

- Khusdash – The ‘Practical’ Brotherhood

- Mamluks and Mangonels

- The Numbers Game

- Cultural “Idiosyncrasies” of a Military State

- The Rise of the Burji Mamluk Sultanate

- The Decline of the Mamluk Dynasty

- Mamelukes – The Mamluk Corps of Napoleon

- The Massacre of the Citadel

Origins of Mamluks and the Ghulam Connection

In terms of etymology, a ‘mamluk’ in Arabic simply means ‘purchased slave’, derived from the past participle of malaka – ‘he possessed’. In essence, it refers to slaves or a class of slaves, usually of non-native origin (predominantly Turkic), who were bought and educated by the local Ayyubid (Saladin’s dynasty) rulers, amirs, and nobles. These recruits, in turn, were expected to fill up positions in the administration and more importantly, serve as loyal followers of the sultan and his amirs.

Over time, the sultan formed his core bodyguards and crack troops from these slaves – as is evident from the recorded Jamdariyah guard and the Bahriyah regiment. However, the increased dependence of the king on the Mamluk units rather enhanced their influence and fueled their political ambitions. This was especially significant because most of these elite troops were stationed in Cairo, the most important city of the Ayyubids.

Furthermore, there was a rampant power struggle in Egyptian politics between the successors of Saladin. For example, Saladin’s brother Al-Adil took control of the Ayyubid state by imprisoning many of the throne contenders and incorporating their defeated Mamluk retinue into his own army (circa 1200 AD). The same strategy was followed by the later Ayyubid rulers who kept on ‘inheriting’ the defeated Mamluk retinue of their rivals.

Finally, during the reign of the last Ayyubid sultan al-Salih (1240-49 AD), the ruler desperately tried to strengthen his military grip over the fragmenting kingdom by recruiting even more numbers of such Mamluks. These slave troops usually comprised the Kipchaks and other Turkic elements – who, in turn, were available in larger numbers, mostly due to their displacement by the devastating Mongol invasion of Russian and Ukrainian lands.

And quite unsurprisingly, it was these power-craving elite slave soldiers who ultimately led a rebellion and overthrew Salih’s son, thereby paving the way for their own Bahri Mamluk Dynasty and kickstarting the Mamluk Era from 1250 AD in the Middle East. This First Mamluk period existed till 1382 AD, mostly dominated by the slave warriors of Cuman-Kipchak origins.

And interestingly enough, while we tend to identify Mamluks with medieval Egypt of the 13th century, a similar practice of military slavery existed in the Muslim world at least since the early 9th century. For example, the Abbasid Caliph al-Mu’tasim (reign – 833–842 AD) was known to have recruited Turkic mercenaries and soldiers, called the Ghulams (or Ghilman) who came from outside the traditional borders of the Caliphate.

And much like the Mamluk Sultans of Egypt, these slave soldiers (of the preceding centuries) went on to wield their own political influence in the royal court – so much so that by the late 9th century, some of them simply acted as the king-makers who controlled the Caliphs themselves. A few also went on to create their own autonomous dynasties in different parts of Central and South Asia.

The Mamluk System – Slave-Soldiers?

In our article about the Ottoman Janissaries, we talked about how “the classification of a slave in medieval Islamic society is rather misleading if perceived through the lens of our modern sensibility.” Simply put, ‘slaves’ or ‘warrior slaves’ in the 13th-century Egyptian realm were recognized as a rather exclusive class (as opposed to the commoner serfs of Europe) – since they tended to be better educated and had higher standards of living when compared to average citizens.

Simply put, while they were denied some rights and could be treated as property, in the practical scheme of things, slaves (especially the warriors and courtiers) could move up the social ladder and take up positions of importance in the state administration during the Mamluk period.

This relative scope of high status (albeit with its lack of freedom) was known among the Turkic and Kipchak tribesmen – many of whom voluntarily allowed themselves to be ‘bought’ and recruited for the Mamluks. To that end, according to historian David Nicolle, their first master often pertained to the khawajah, the slave merchant who maintained his trade contacts outside the borders of the Sultanate.

The green recruits were often gathered inside the tabaqah – the slave market inside the Citadel of Cairo. And while it does sound reprehensible to our modern conscience, in accordance with 15th-century standards, their average price (on an individual basis) via auctions often fetched more than three to four times that of a prized warhorse.

Interestingly enough, it was not only the fighting men who were prized as Mamluks. Based on their traditions of gender equity (norms that were rather alien in the 13th-century tenets of medieval Islam), the Turkic and Kipchak men also brought forth their female companions, wives, concubines, and daughters.

Many of these female companions, comprising both free and slave women, were integrated into the Mamluk system. A few, marrying into the ruling families, even wielded their influence on the political side of affairs.

And beyond just the Turkic Kipchak elements, the Mamluk system also incorporated (although rarely) slave recruits from other ethnicities. For example, it is recorded in medieval Egyptian sources that 4,000 battle-hardened and well-equipped Arab warriors from the Banu Murra tribe were recruited into the Mamluk ranks circa 1280 AD.

Similarly, the Mamluks also employed African slaves, but only a few of them played military roles. Some, however, like African eunuchs, were employed in military schools for the training of young Mamluks.

Training and Skills of the Mamluks

As mentioned before, the first Mamluk power pertained to the Bahri dynasty. It started out as a regiment of elite slave warriors (Bahriyah) under the Ayyubids but later toppled their masters. Incredibly enough, in stark contrast to near-contemporary military units (like the Knights Templar), the scope of training for these early Mamluks is well documented, via their extensive furusiyya (the science of martial exercise) manuals.

The integral part of the Mamluk martial exercise was a specified field known as the maydan (or maidan) – used as the training ground. Sultan Baybars is known to have constructed at least two of these huge maidans near the Citadel of Cairo. These fields were known to have state-of-the-art facilities, including wells, drinking fountains, resting spaces sheltered by palm trees, water wheels, stables, and even opulent quarters for the Mamluk sultans, emirs, and their personal retinues.

Interestingly enough, many of these training exercises possibly even doubled as spectator sports, given the sheer range of martial maneuvers practiced by the Mamluk soldiers. To that end, these elite slave warriors were trained in engaging with the lance from horseback, polo, archery practiced at both ground targets and high targets, fencing with swords, using heavy maces, wrestling, hunting, horse racing, and quite intriguingly shooting a special type of a blow-pipe (known as zabtanah) that discharged pellets.

Such a diverse kind of training was not only for the spectators at the maidan. They were also tailored to instill an innate nature of discipline in the new recruits – so as to maintain a continuation of Mamluk practices in both horsemanship and archery.

And according to historian David Nicolle (and the general consensus among most researchers), it was archery from horseback that was probably the trademark of the typical Mamluk cavalryman from the 13th-14th century AD. In that regard, as opposed to shooting while moving, the Mamluk soldiers were known to have preferred shooting from a stationary position – so as to maintain higher rates of arrow volleys with precision.

For example, an expert Mamluk horse-archer was expected to hit a target of less than 1-meter size from a distance of 75 meters (246 ft) – and that too while shooting three arrows in a space of one and a half seconds. Furthermore, some furusiyya manuals also mention the use of crossbows from horseback, possibly as a substitute (of the composite bow) for relatively inexperienced Mamluk auxiliaries.

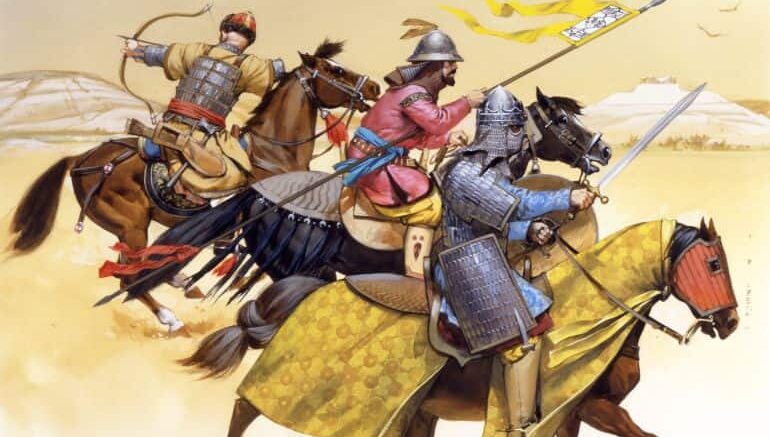

A Military Stratagem ‘Fueled’ by Mongols

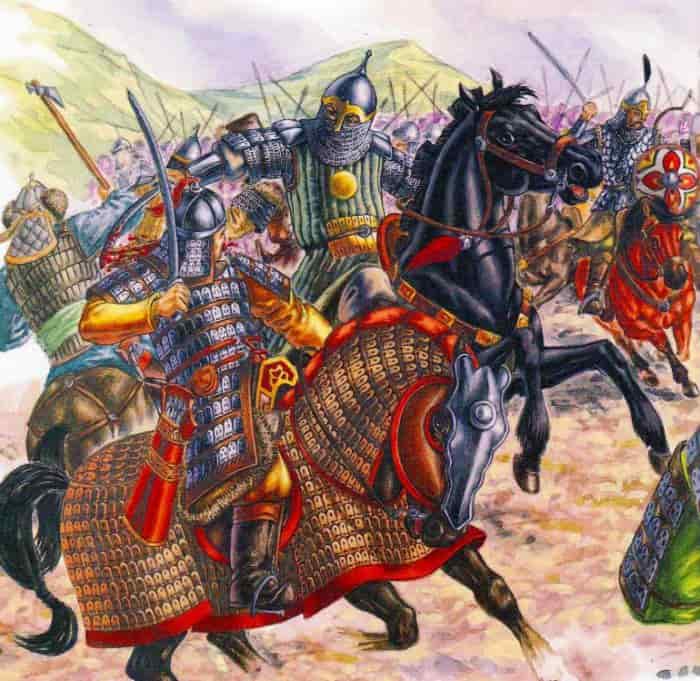

It can be hypothesized to some degree that the Mamluk mode of horse archery (like shooting from fixed positions) was developed as a counter to the mass cavalry formations of the Mongols, rather than to the charges of the Crusader knights. To that end, the Bahri Mamluks are often credited with stopping the Mongol onslaught into the Middle East and the Levant. They defeated their agile foes at the Battle of Ayn Jalut circa 1260 AD, under the leadership of Mamluk Sultan Qutuz.

Interestingly enough, as a means to deal with the mobility of the Mongol army, the Mamluks might have practiced the burning of dried grasslands north of the Euphrates River – thereby denying the main source of nourishment for the enemy horse herds. The relatively stony landscape of Syria was also not suited to the unshod Mongol ponies. In contrast, the Mamluk warhorses were generally stall-fed and protected by horseshoes.

Furthermore, as we mentioned before, many of the Mamluks themselves were recruited from the Kipchak and Turkic tribes that were affected (or afflicted) by the Mongol invasions. Thus some of them must have had a level of understanding of Mongol tactics.

Moreover, after the momentous defeat of the Mongols at Ayn Jalut, bands of Mongol refugees joined the Mamluk armies. Known as Wafidiyah, these dissident Mongol warriors were treated as free soldiers who were recruited into various regiments (as opposed to a single unit). These ‘renegade’ Mongols brought forth their fair share of experience in mounted warfare and steppe tactics to the Muslim forces.

And quite interestingly, the Mamluks were also known to have practiced large-scale hunting, much like the Mongols – in organized bands to effectively approach and cordon off their hunt, thereby replicating real-time battle scenarios involving mobile foes. Essentially, it was this overarching mode of maneuvering and counter-maneuvering that was perceived as an efficient tactical scope by the highly-organized Mamluk forces.

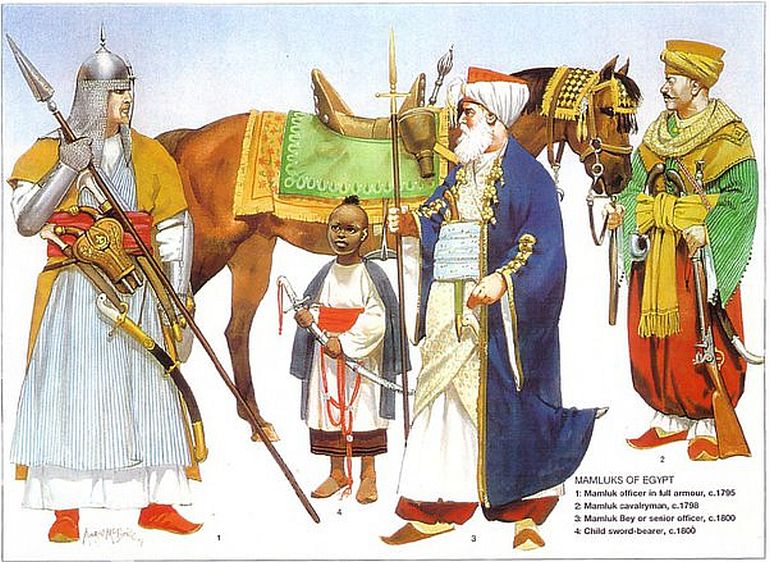

Armor and Weapons of Mamluks

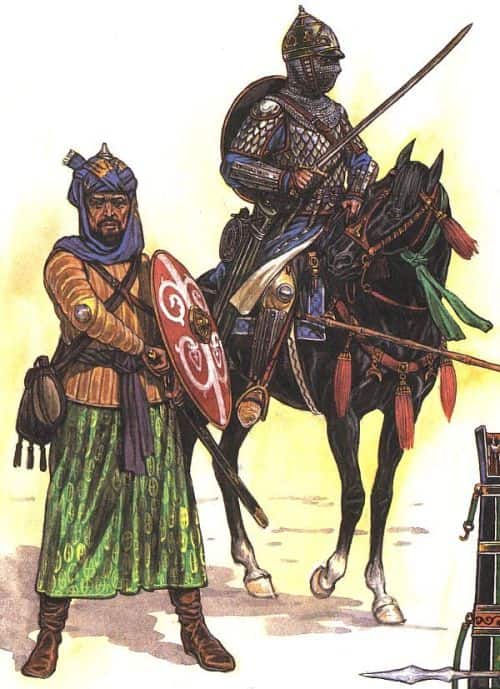

A Mamluk, after being selected in the elite corps (of the Sultan or the senior Mamluk emirs), was presented with his first set of armor. But as he grew in rank, he was expected to acquire better armor with his improved economic means – thereby mirroring his higher status within the army. For example, the Sultan’s personal Mamluks were probably equipped with the finest arms and armor, sourced from the upscale workshops situated in the largest cities of Egypt and the Levant.

As for the general armor types, furusiyya manuals do mention the complete kit of a fully equipped Mamluk lancer. For example, by the early 14th century, the Mamluks were required to wear the dir hauberk made of mail, while some wore a lamellar jawshan chest piece (and other lamellar extensions) over the mail coat for added protection.

In order to achieve some form of flexibility, Mamluks may have also worn the qarqal between the jawshan and the dir, and it generally comprised a padded cloth often reinforced with scales. And by the late 15th century, the Mamluks began to adopt the mail-and-plate type composite armor, possibly known as the libas al hadid al munaddad.

As for the protection of their heads, many junior Mamluks were equipped with turban-like gear with extending reinforcements, while the senior members probably preferred their one-piece iron helmets with nasal guards.

Coming to weapons, given the Mamluk lancers’ versatile mode of training they were possibly equipped with a variety of arms, ranging from lances, and swords, to maces. However, the characteristic weapon associated with the early Mamluks probably pertains to the powerful composite bow, which once again harks back to the influence of the Mongols (as opposed to the Crusaders).

This main bow type was also complemented by specialized weapons, like the aforementioned zabtanah blow-pipes (that were later referred to as the early Persian handguns) and advanced crossbows.

The Tactical Flair of the Mamluk Regiments

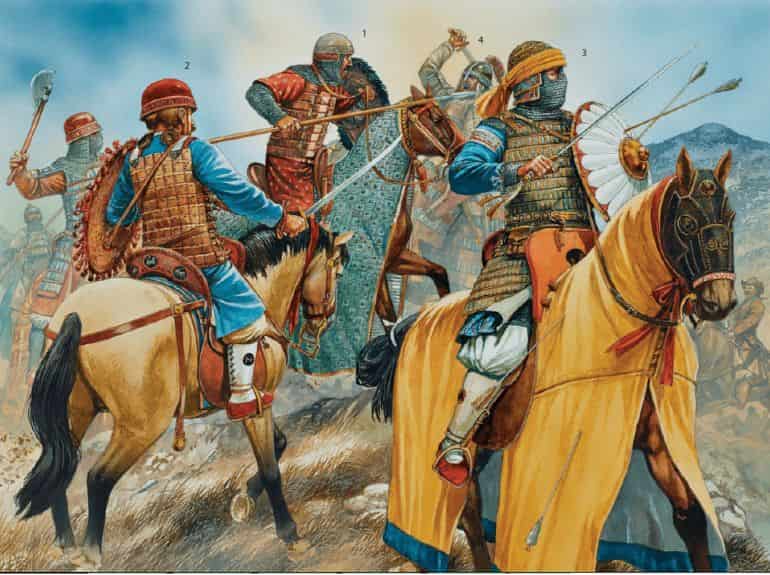

As can be discerned from the training modes and the variety of weapons carried by Mamluks, their tactical approach to the battle was not confined to a singular role (like that of a European knight). So as opposed to just charging the enemy formations, Mamluks were also trained to feign retreats and make use of their equestrian skills to evade and maneuver the formations.

The latter skillset possibly reflects their penchant for horse archery – which proved to be the bane for many ponderous Crusader armies reliant on the ‘conventional’ units of infantry and cavalry. One pertinent example would relate to an encounter at Gaza in 1244 AD where a full Crusader charge was stopped by the crippling arrow shower from the mobile Mamluk positions. On the strategic level, Mamluk support played a crucial role in defeating the Seventh Crusade of King Louis IX of France, in 1250 AD.

Alluding to the flexibility of tactics, on some occasions, the Mamluks might have even preferred to close in with the Mongols for melee combat scenarios. In essence, they were also suited to charging the enemy lines (if the situation allowed so), especially in scenarios where they could take advantage of their heavier weapons and armor to break the formations of the foe.

Similarly, the Mamluks were also prepared to receive charges from the foe – thus alluding to their training-induced mentality and morale. Furthermore, according to historian Davide Nicolle, some of the elite senior Mamluks could even dismount and fight on foot while also specializing in setting up defensive parameters and field fortifications.

These tactical elements were complemented by raids (designed to cut off enemy supplies), choosing effective battlefield locations based on the sun orientation and the wind directions, and proper use of infantry as support units (as was the case in the Battle of Ayn Jalut where infantrymen chased and surrounded the beaten Mongols in the mountains).

The Sultan’s Mamluks

Unsurprisingly, the highest-ranked Mamluks often came from the ranks of the young slaves who were bought by the Sultan himself. These young teenagers referred to as the kuttub students were enrolled at the special tabaqah schools for proper education, etiquette, and religious indoctrination.

By the end of the schooling, the candidates were offered uniforms, horses, weapons, armor, and even a certificate. And on reaching adulthood, many of these young men were ‘freed’ and recruited as the Sultan’s own Mamluks, known as the mushtarawat or jublan (which alludes to their youth).

Simply put, the disciplined schooling and the strenuous training rather enhanced the esprit de corps of these Mamluks, who were designated as the loyal and almost officer-like units of the medieval Egyptian army. The khassakiyah (or khassaki) were the elites even within the Sultan’s Mamluks, and they were chosen as the heavily-armored bodyguards and the cracks units (sometimes also selected for political duties).

Interestingly enough, these young Mamluks of the present Sultan were also rivaled by the mushtakhdamun, the Mamluks of the previous Sultans. To that end, while most of the Sultan’s Mamluks were offered the choicest iqtas (lands or estates), the elite soldiers were demoted (by the next ruler) on the death of their patron, which created a non-hereditary system wherein the Mamluks could only be loyal to the present Sultan.

On the flip side, the new Sultan often faced a dearth of experienced troops and thereby had to rely on the older Mamluks (or qaranis) for conducting the difficult campaigns, in spite of their reduced payscale, holdings, and possibly even loyalty.

Khusdash – The ‘Practical’ Brotherhood

Like many military fraternities, the Mamluks, in spite of coming from different regions outside the traditional borders of Islam, developed their bonds and camaraderie based on a mutual sense of loyalty to their masters. The esprit de corps was rather bolstered during the training period, and thus the groups of young men tended to form fellowships in such military schools.

Interestingly enough, many of these members were often bought, trained, and released together – by their masters. And so, even when they served as Mamluks, driven by their camaraderie, the slave soldiers maintained their fraternity.

Over time, much like ancient Roman contubernium (tent group), the groups morphed into a brotherhood of sorts known as the khusdash. However, beyond just the emotional bond shared by the members, the khusdash was also fueled by the practicality of circumstances including sealed agreements involving the sharing of money.

Furthermore, if the master of the khusdash died, the entire unit (as opposed to individual Mamluks) was to be bought by a new master. Unsurprisingly, historian David Nicolle compared it to 21st-century businessmen who formed their own organizations.

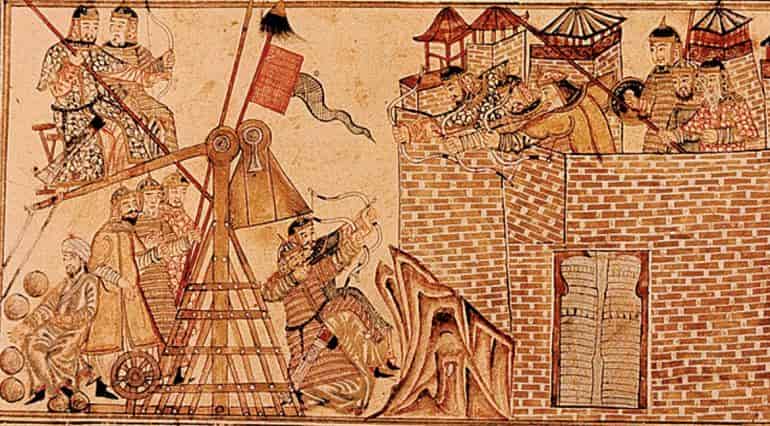

Mamluks and Mangonels

Possibly due to the combined effect of the Crusader pressure and the Mongol onslaught, the 12th-century Islamic world was rather forced into the renewed adoption of military technologies that could provide them with momentary advantages.

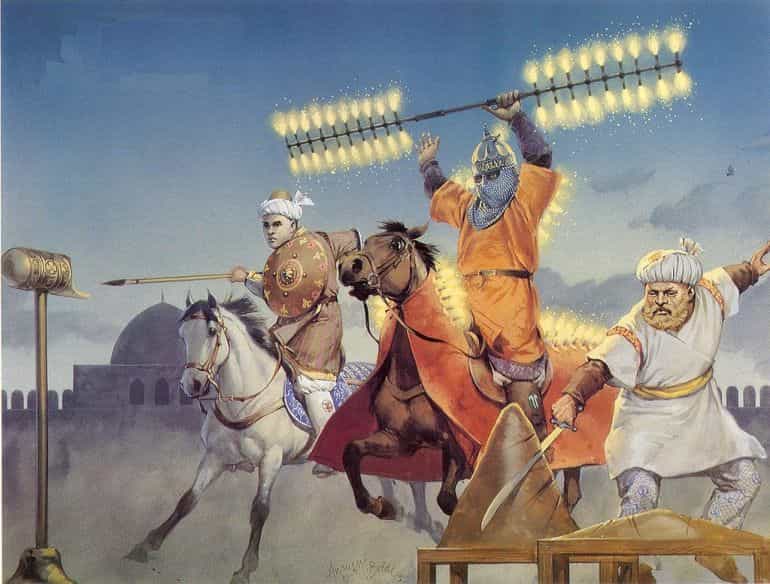

The Mamluks inherited this proverbial scope of “necessity being the mother of all inventions”, and as such were known for their investment and innovations in siege warfare. One of these innovations pertained to the use of various types of mangonels that could throw different projectiles, ranging from boulders, and arrows, to even naft (Greek fire).

Some of these 13th-century powerful siege weapons, like the maghrabiyah (‘North African’), could hurl 110 lbs to 500 lbs stones at a distance of over 300 yards (900 ft). While others, like the aptly named shaytaniyah (‘devilish’), operated by traction power, could fire volleys of specialized arrows at a rapid speed.

And beyond just the technology, it was the sheer scale of siege warfare conducted by the Mamluks that separated them from their Ayyubid predecessors. For example, it is estimated that the Mamluks used more than 70 siege machines (including powerful mangonels) for the famous Siege of Acre, one of the last Crusader strongholds, in circa 1291 AD.

Other more exotic weapons used during both besieging and defending included fire-based weapons like the qawarir al-naft (fire pots with distilled petroleum) thrown by mangonels, qidr iraqi (Iraqi pots) shot by giant crossbows, sawarikh firecrackers (used for frightening enemy horses), and even makahil al barud (possibly an early variant of a cannon, used in circa early 15th century).

The Numbers Game

When it comes to just numbers, it should be noted that Mamluks just formed a tiny part of the medieval Mamluk Sultanate army. Moreover, mostly serving as a cavalry force, these Mamluks were divided into the Sultan’s Mamluks (who formed the elite and were usually stationed around Cairo) and the amirs’ Mamluks (basically the slave-soldier retinues of the nobles who were usually ranked lower than the Sultan’s retinue). Both were accompanied by the free-mounted troops known as the halqa (who were later relegated to a secondary infantry force by circa mid-15th century).

Furthermore, since the Mamluks fought most of their battles in Syria (as opposed to Egypt proper), the professionally mounted forces were invariably supported by infantrymen from various walks of life, ranging from disciplined to ill-equipped, who proved their worth in siege scenarios.

Delving into figures, according to the estimation of historian David Nicolle, the Mamluk army totaled around 40,000 troops in the late 13th century (during Baybar’s reign), of which only 4,000 were actual Mamluks. By 1315 AD, the number of Mamluks in Egypt rose exponentially to 24,000 men – but more than half of them came from the retinues of the amirs.

And these regiments were possibly bolstered by a further 13,000 ‘provincial’ Mamluks operating in Syria and the Levant. However, by the late 14th century, the number of Mamluks fell, possibly because of a series of plagues and civil wars. The latter resulted in a regime change that brought forth the Burji Mamluks (of mostly Circassian origin) in place of the Bahri (of mostly Turkic background) as the ruling dynasty.

Cultural “Idiosyncrasies” of a Military State

As we mentioned before, the Sultan’s Mamluks were accustomed to settling in Cairo, the capital and the political center of the Sultanate. And while they maintained their veneer as pious soldiers known for their endowments to religious causes, the Mamluks also tended to opulently flaunt their wealth and high status.

This was done through expensive attires and a penchant for ‘forbidden’ entertainment – thus displaying boisterous behavioral patterns (much like the Varangian Guards) that could be perceived as being scandalous by the ordinary citizens of the Islamic realm. But such acts were usually ignored by the Muslim clerics, given the sheer military value and power exhibited by the Mamluk authorities in both medieval Egypt and Syria.

In fact, most Mamluks were proud of their Turkish heritage and thus preferred their Turkish style of dresses over the native Arab attire – which also visually set them apart from the local populace. Moreover, while there were no particular uniforms for these slave warriors, some, especially the officers, displayed their expensive garments and zamt hats in striking colors of yellow and red.

The Mamluks may have also developed a form of heraldry that was primarily used as ‘trademarks’ of ownership over workshops, factories, and even horses rather than as a ‘coat of arms’ for banners and flags.

The Rise of the Burji Mamluk Sultanate

By the latter half of the 14th century, the Turkic and Kipchak candidates in the ranks of Mamluks were gradually outnumbered by the subjects (many even originally Christian) who made their way from the southern parts of Russia and Caucasus.

These Circassians ultimately overthrew the Turkic Bahri (River) Dynasty of the Mamluks to install their own Burji (Tower) Dynasty circa 1382 AD, thus kickstarting the second phase of Mamluk history that went on till 1517 AD.

However, from the militaristic perspective, the Circassians of the 14th century were considered relatively ineffective when compared to the resourcefulness of the earlier Turkic and Kipchak recruits.

Furthermore, while earlier generations of Mamluks were known for working within the system and its hierarchal structure, the Burji Mamluks and the associated Circassians tended to influence the system by bringing their own family members from distant lands. Over time, the ruling class and the elite soldiers gave preference to their extended families and clans for the positions of the senior ranks within the Mamluk structure.

Simply put, family connections were considered important markers rather than martial ability and training. This brought forth elements of partiality and nepotism that eroded the military effectiveness of the Mamluks in the long run. Moreover, as an aftereffect, the local soldiers tended to be more loyal to the regional Mamluk commander rather than the Sultan – thus creating even more strife and fracture within the Mamluk Sultanate.

The Decline of the Mamluk Dynasty

The effect of the regime change was felt in the military of 15th-century Egypt and Syria. This was mostly due to the Mamluk class (tied by relations rather than camaraderie) beginning to exhibit symptoms of apathy and entitlement, with less focus on martial pursuits and more on political machinations.

This, in turn, resulted in greater internal rivalries and dissensions that further corroded the military system – thus leaving the Sultanate exposed to external threats, like the Timurids and the Ottomans. Pertaining to the former, Timur invaded Syria in the year 1399, resulting in the devastating sacking of two major Mamluk-controlled cities – Aleppo and Damascus.

Furthermore, the Mamluks suffered a chronic shortage of manpower (in terms of new recruits) in both Egypt and the Caucasus – because of the afflictions caused by plagues. Interestingly enough, a significant portion of the Mamluk Sultanate’s economy was dependent on the trade routes operating in the Red Sea and connecting to India (in fact, India was probably one of the sources for the heavy warhorses used by the Sultan’s Mamluks).

However, the Portuguese, by virtue of Vasco da Gama’s explorative endeavors, established their trading outposts along the coastlines of western India and Yemen, thereby disrupting the Egyptian routes. Consequently, over time, the debt-ridden Sultanate had to loan financial assets from the various banks in Venice – which further soured their relations with other contemporary Islamic powers, like the Ottomans.

On the military front, due to a series of political fallouts, the Ottomans began to annex Mamluk dependencies in what is now southeastern Turkey. And finally, after inflicting a crushing defeat on the Safavid Persians (at the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514 AD), Ottoman Sultan Selim I turned all his attention toward the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt proper.

The slave warriors by this time probably numbered over 15,000 – but their core Mamluk cavalry, in spite of showing courage and spirit, were no match for the disciplined Ottoman Janissaries and artillery.

In fact, many scholars hypothesize that much like the Safavids, the Mamluks were late to incorporate gunpowder weapons, possibly because of their hesitant attitude and unwillingness to adopt newer technologies (which was in stark contrast to the 13th-14th century Mamluk state).

And so finally in 1517 AD, Cairo fell to the invading Turkish force, and the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt was effectively conquered by the burgeoning Ottoman Empire. Incredibly enough, even after their defeat, the Mamluks were still recognized as a separate military class. And as such, the Ottoman Empire retained many of the Burji amirs and commanders as Egyptian vassals of the Ottoman state.

Mamelukes – The Mamluk Corps of Napoleon

After Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt in 1798 (during which his forces faced off against the native Mamluks), the French general Jean Baptiste Kléber created an auxiliary mounted force of 300 men. This Mamluk corps, known as the Mamluks de la République (or ‘Mamelukes of the Imperial Guard’), was composed of the combined units of ex-Mamluks and Syrian Janissaries. According to some sources, many of these men were recruited from the 2,000 slaves that Napoleon bought (and later released) from a Syrian merchant.

By 1803, the companies of the Napoleonic Mamelukes were attached to the light cavalry divisions of the Chasseurs à Cheval de la Garde Impériale (or ‘Horse Chasseurs of the Imperial Guard’). In the following years, the units expanded and widely recruited men from different ethnicities, including Greeks, Egyptians, Arabs, Turks, and Georgians, and as such, were known to have showcased their effectiveness at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805.

And also befitting their exotic status within the French army, the Mamelukes, armed with sabers (often conspicuously curved), maces, axes, daggers, and two braces of pistols, were also attired in vibrant vests, loose shirts, red saroual (trousers), and white turbans. Unfortunately, in spite of their relatively good track record in battles, Napoleon’s own Mamluk corps was probably unceremoniously disbanded after the Second Bourbon Restoration of 1815.

The Massacre of the Citadel

By the early 19th century, the Mamluks, while losing their crown and state, still clung to their provincial wealth. Simply put, the native Mamluks had become feudalistic in nature, boasting their rich estates and economic power. Many of these beys (chieftains) even played their rebellious role in the struggle for Egyptian independence from both the Ottoman Turks and Great Britain.

Wary of the rising power of this autonomous Mamluk class, Muhammed Ali Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Egypt (who coincidentally later broke away from the Turkish Empire to create his own dynasty) decided to end the internal threat once and for all.

So in an episode that played out like a political thriller, in 1811, Muhammed Ali invited many senior Mamluk members of the realm to his palace in Cairo – to apparently toast the start of a war with the Wahhabis in the Arabian peninsula. Impressed by the Pasha’s gesture, around 500 Mamluk beys made their way to the capital amidst much pomp and gusto.

But once they were making their way across a narrow passage near the Al-Azab gates of the Citadel of Cairo, an ambush was sprung by forces loyal to Muhammad Ali. In the resultant encounter, also known as the Massacre of the Citadel, almost all the senior Mamluk leaders were slaughtered.

In the following weeks, the Ottoman punitive actions claimed more lives of other Mamluks and even their family members. And while a group of Mamluks was able to flee to Dongola in Sudan, most of the members were pursued and dispersed by an Ottoman expeditionary force, thereby resulting in the total breakdown of the Mamluk power in Egypt and Syria. On an official level, Muhammad Ali may have pardoned many of these Sudan-bound beys, but only a few of them returned to Egypt.

Book References: The Mamluks 1250 – 1517 (By David Nicolle) / The Mamluks in Egyptian and Syrian Politics and Society (By Michael Winter and Amalia Levanoni)

Online Sources:Encyclopedia.com / Jewish Virtual Library / BBC

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork, or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "Mamluks: The Incredible Islamic Slave Warriors of Egypt"