Introduction

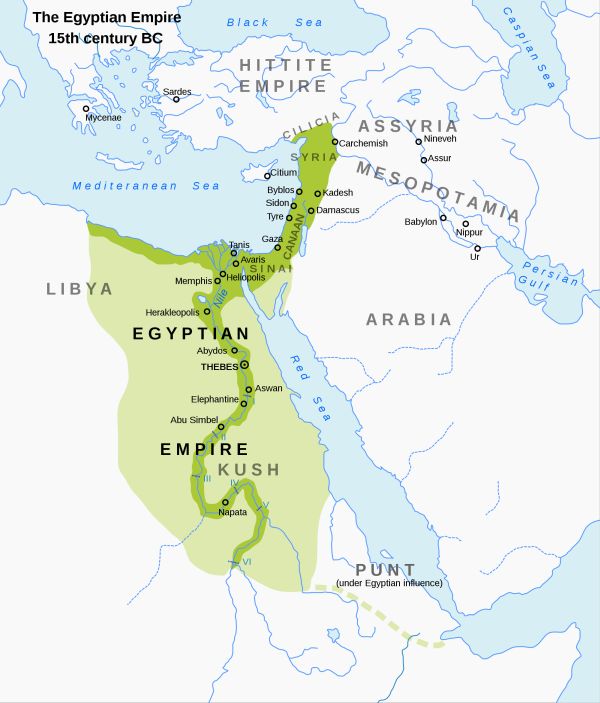

The New Kingdom of Egypt, roughly corresponding to the period between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC (encompassing the 18th, 19th, and 20th Dynasties of Egypt), is often viewed as the Ancient Egyptian equivalent of an empire. And while such a perception is simplistic, especially given the complex political climate of the time, there is no doubt that during the New Kingdom phase, Egypt reached its greatest territorial extent.

The ’empire’ was fueled by imperialistic policies initiated by powerful Pharaohs, and as such Egypt reached its commercial as well as military peak. Symbolically, the New Kingdom of Egypt was also perceived as the native power that broke the shackles of the ‘foreign’ Hyksos rule (during the Second Intermediate Period). These native rulers, in turn, proceeded on to conquer regions and retained vassals beyond the traditional boundaries of the kingdom, including ancient Nubia, Levant, and Syria.

Considering all these historical factors, we have chosen the New Kingdom of Egypt (among all the Ancient Egyptian periods) to showcase its military-oriented prowess. So without further ado, let us take a gander at the history of the Ancient Egyptian soldiers of the New Kingdom.

Contents

- Introduction

- Pharaoh – The Supreme Warlord of Ancient Egypt

- The Ancient Industry of War

- The Massive Egyptian Military Structure

- The Valor of Gold

- The Archery Tactics of Ancient Egyptians

- The ‘Strong Arm Boys’

- The Unique Egyptian Chariots

- The Runners Beside Chariots

- The Allied Troops of the Egyptian Army

- The Ancient Egyptian Navy

Pharaoh – The Supreme Warlord of Ancient Egypt

Much like the modern office of the American president, the Egyptian Pharaoh was considered the head of the state as well as the supreme commander of the armed forces. But unlike his modern-day counterpart, the Pharaoh also boasted absolute control over his kingdom’s resources and the administrative sector.

Such an incredible scope of wielding unconditional power was complemented by the Pharaoh’s association with divine entities. For example, various Egyptian inscriptions and iconography (especially from the 18th and 19th dynasties period) depict Pharaohs in the style of the sun god. Some of these portrayals even project the Pharaohs as incarnations of the god of war and valor Montu (falcon god) or as personifications of Egypt itself.

Suffice it to say, the Pharaoh was the most important figure in the state machinery of ancient Egypt. Consequently, he was provided with the military education befitting a supreme commander of an empire. This training for warfare, often imparted by state-appointed veterans, not only included physical regimens and weapon-handing but also entailed lessons in tactical and strategic planning (with the latter being far more important for military campaigns).

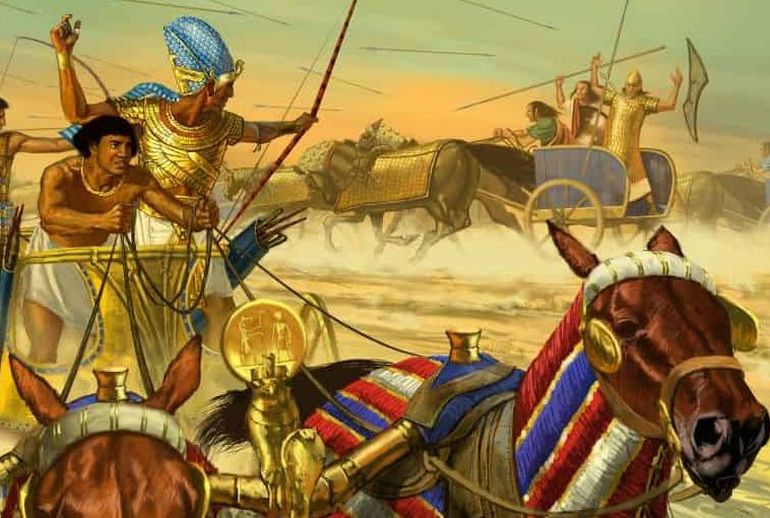

And as documented events had proven, the Pharaoh epitomized the spearhead of the Egyptian army with his elite chariot corps. This suggests how the rulers, with examples like Amenophis II and Ramesses II, took particular pride in maneuvering chariots, handling bows (perceived as a weapon of esteem), and personally leading their armies in battle.

On the other side of the proverbial coin, much like their Assyrian contemporaries, the Egyptian state was overly dependent on its ruler. Consequently, a weak ruler usually mirrored the ‘bad times’ faced by the empire; though luckily in the case of Egypt, many New Kingdom pharaohs exhibited their strong-willed leadership.

The Ancient Industry of War

The ancient armies from circa 16-11th century BC were sustained by the military-oriented state machinery of the New Kingdom. For example, Ahmose I, the founder of the Eighteenth dynasty (reign 1549–1524 BC), reorganized his band of warriors into a full-fledged standing Egyptian army of the Late Bronze Age. This was a far cry from the Old Kingdom period (2686–2181 BC) when farmers were seasonally enlisted to fight for their country.

By this time, many soldiers were actually drawn from specific warrior castes, which in turn hints at a societal solution for a professional (or at least semi-professional) army. Now of course, beyond just the scope of the manpower, the ruler also had to equip his newly formed Pharaoh’s army – and that is where the state-run industries entered into the equation.

In that regard, the very large number of bronze weapons, like the famed khopesh swords and arrowheads, could only be supplied by an effectively organized military infrastructure. These industries often consisted of interconnected networks of gathering and distribution centers for raw materials, arsenals for weapons manufacturing, dedicated workshops for producing defensive equipment like shields and chariots, and dockyards for crafting ships and boats.

Interestingly enough, the Egyptians even went on to create state-funded stud farms and grazing grounds for horses that were needed for chariots. These highly-prized animals were also taken as tributes from vassals based in the Levant and from defeated foreign powers.

Simply put, the ancient Egyptian army looked forth to conquer and integrate more territories from ancient Syria and Nubia in a bid to tap into the resources provided by such rich regions, thus fueling a cyclic scope of warfare and economy.

Furthermore, there was also a symbolic veneer to the expansion of the New Kingdom army in Egyptian history. In many ways, the rulers and the commanders perceived the proximate nations (like Libya and Nubia) as eternal threats to the tranquility of the fertile Nile River valley of Lower Egypt. In fact, even the earlier Middle Kingdom period (circa 2055 BC–1650 BC) saw Egyptian military campaigns extending into Nubia.

The Massive Egyptian Military Structure

As can be comprehended from the dedicated avenues of the standing Ancient Egyptian army of the 15th century BC, the empire took its military force and related strategic scope quite seriously. The structure of the military administration mirrored such a proactive outlook, with the main garrison headquarters established in the north and south of Egypt, at Memphis and Thebes respectively.

By the time of the great Ramesses II (or Ramses II), there were four military headquarters spread across the burgeoning Egyptian empire, each named after the god of the region while being commanded by the chosen senior officers of the army. This Egyptian army, in turn, was divided into three major branches – the Infantry, the Navy, and the Elite Chariot Corps.

These massive military complexes were used for training new recruits, creating supply and reinforcements points, providing royal escorts, and even parading troops during triumphal occasions. The high-ranking officers were aided by military scribes (controlled by dedicated state-appointed officials) who were responsible for maintaining a plethora of records, including the number of new recruits and more importantly army rations and supplies.

In essence, this type of systematic administrative networking and record-keeping rather reflected the long scribal tradition of ancient Egypt, which rather made the campaign-conducting capacity of the late Bronze Army more effective than many of the contemporary kingdoms.

The Valor of Gold

Interestingly enough, much like the later-day Roman legionaries, the ordinary soldier of the Ancient Egyptian army was possibly motivated by the allure of wealth and social progression. Simply put, while the sons of nobles were expected to be inducted into elite corps (like the chariot regiments), even commoners had their chance to progress through the ranks of the military – as can be attested by one Horemheb, a scribe who went to become the last pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt.

To that end, bravery was seen as an important benchmark for choosing high-ranking leaders; and as such the selected men (who had proven their value in battles) were rewarded with the ‘valor of gold’. This was a military tradition that entailed ostentatious gifts of gold ornaments and objects being presented to the candidates.

Of course, beyond just gold, many of the officers could claim their fair share of land grants, booty, and slaves. Furthermore, by the 14th century BC, the pharaohs created a separate military caste which was basically hereditary in its nature. This provided a steady supply of manpower for a standing army (much like the Kshatriyas of India).

These semi-professional soldiers were housed across the various military colonies of the country while being trained and sustained by the aforementioned army headquarters. It should also be noted that while the semi-professional army formed the core of the ancient Egyptian military, these soldiers were also accompanied by conscripted men. Many of the conscripts were forcibly enlisted (with ratios going as high as one in ten men) to bolster the ranks.

The Archery Tactics of Ancient Egyptians

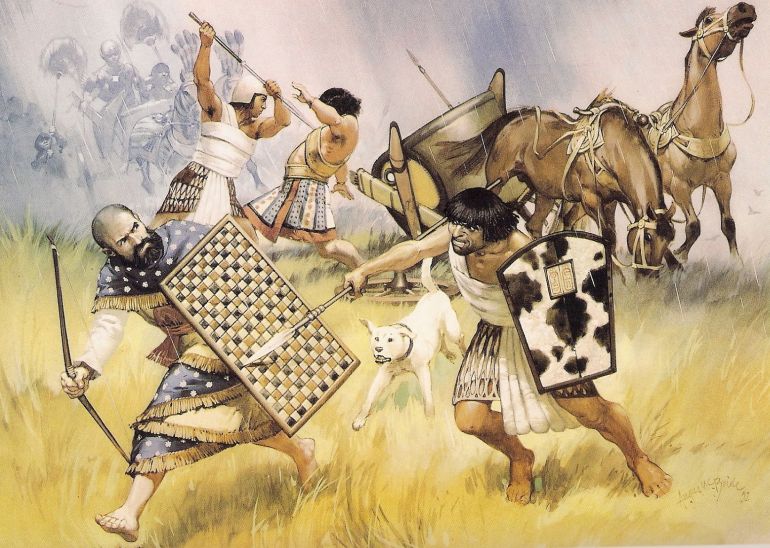

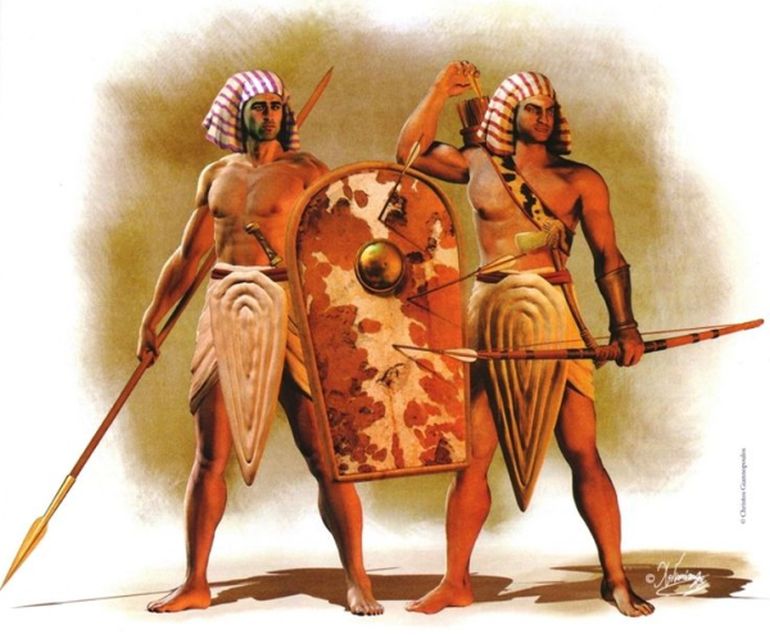

The ancient Egyptian infantry mainly comprised archers and melee fighters. The former were either equipped with regular stave bows (possibly for the conscripts) or better composite bows (handled by the regular soldiers).

In fact, composite bows were so expensive and in high demand that there were occasions when the Egyptians demanded tributes in the form of the composite bow instead of gold. As for arrows, some of the bronze-tipped specimens, sourced from the plentiful reeds of the Nile, were specifically fletched with three feathers to enhance their projectile accuracy.

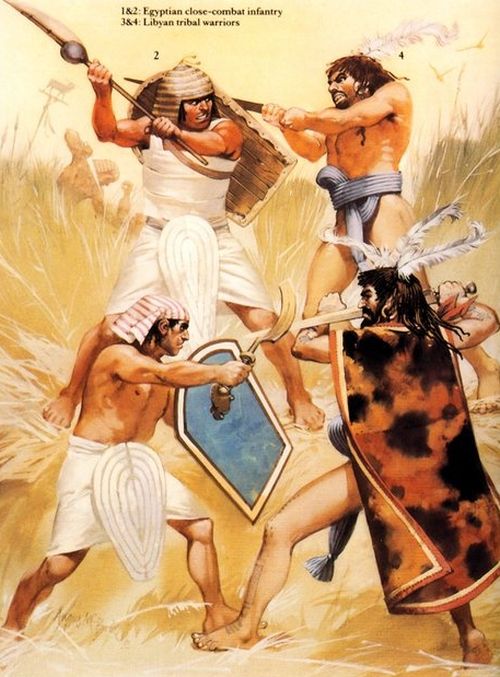

And while many of the archers formed single lines on the battlefield, their shooting tactics differed based on the enemy they were facing. For example, when facing the lightly-armored Libyans from the neighboring realms, the Egyptian archers showcased their penchant for unleashing mass volleys that usually caused crippling casualties in the ranks of the foe.

However, when the Egyptians tussled with the more heavily-armored enemies from the Near East and the Levant, the archers played their supporting role in the encounters. So during certain scenarios, they offered covering fire for the advancing melee infantrymen (whom we will talk about in the next entry), thus possibly creating a synchronized maneuver on the battlefield.

The ‘Strong Arm Boys’

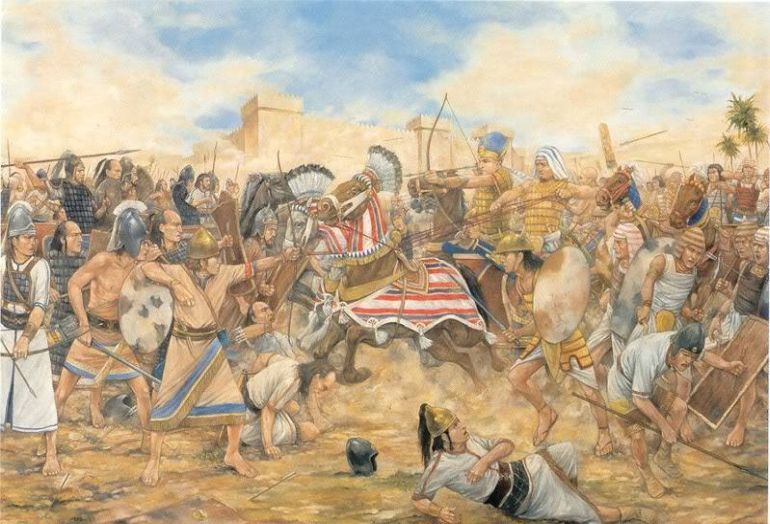

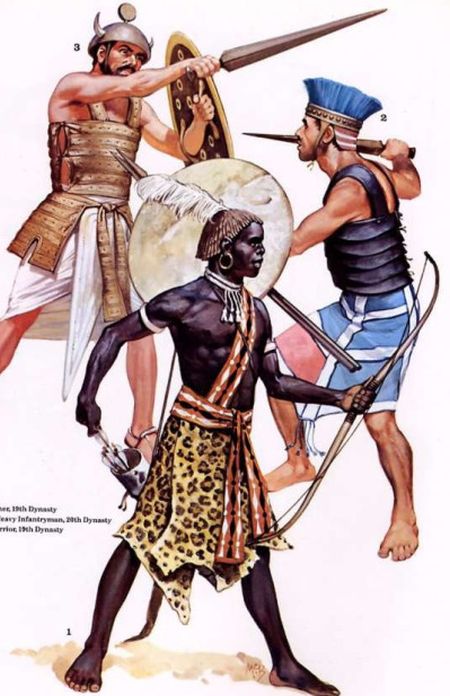

Our popular historical romanticism about the khopesh (sickle sword) wielding Egyptian soldier is probably inspired by their real historical counterparts – the nakhtu-aa (or ‘strong-arm boys’). These close combat shock troops possibly carried a short spear that was thrown at the enemy at close range, much like the Roman pilum, while their melee weapons varied from the bronze khopesh to even bigger battle axes (some shaped like maces).

By the 16th century BC, they also carried larger shields that were beginning to take a rectangular form (corresponding to the 18th dynasty period), which alludes to rudimentary shield-wall formations on the battlefield. Such formations were possibly used in conjunction with cover fire from the archers (although there is no evidence of such tactics). Additionally, some of them did wear armor in the form of light leather-hide vests.

In any case, these infantrymen were grouped into units of around 200-250 men, each furnished with their dedicated battle standards. As can be surmised from historical sources, these standards bore prestigious titles that were rather used to maintain the morale (and cohesion) of many renowned companies, with examples like ‘Splendor of Aten’ and the Nubian ‘Bull in Nubia’.

The semi-professional kingdom soldiers were also accompanied by a host of other light infantry divisions. These conscripts were armed with different kinds of weapons, like spears, small axes, and short swords. One such common Egyptian weapon was the short sword design that had a dagger-like shape with a sharp point.

The Unique Egyptian Chariots

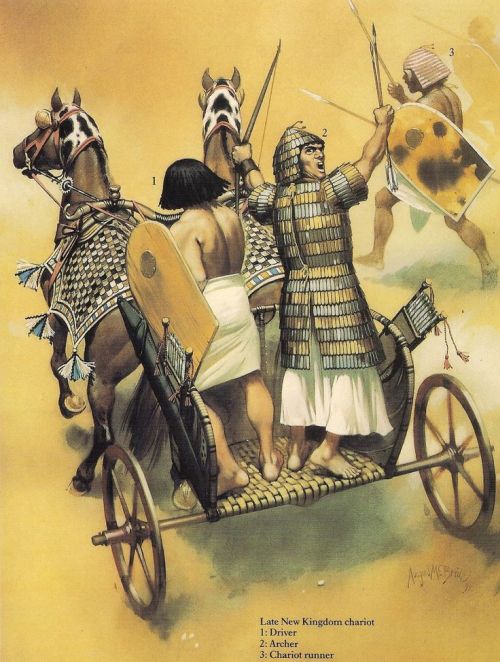

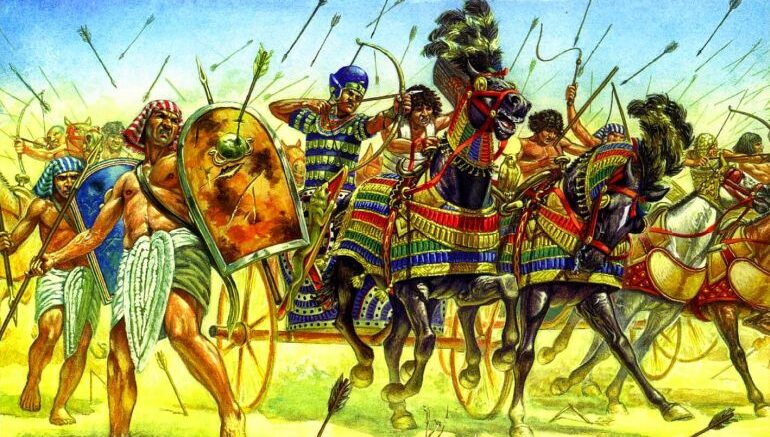

In some ways, the chariots of the Late Bronze Age served the purpose of heavily-armored platforms that often decided the fate of many a battle fought on open grounds (much like latter-day knights and modern tanks). Unsurprisingly, most factions from the Near East, Mediterranean, and Africa made use of such ‘platforms’, ranging from Hittites, and Assyrians to Mycenaeans and Egyptians.

Interestingly enough, when it came to the latter, the ancient Egyptian horse-drawn chariot fulfilled a somewhat different tactical role than their Near East contemporaries. To that end, Hittite, Mitanni, and other Asian chariots tended to be bulky.

Thus their main tactical function related to a ponderous shock charge into the vulnerable formations of the enemy infantrymen, which would have caused a high number of casualties and general chaos among the foe’s ranks.

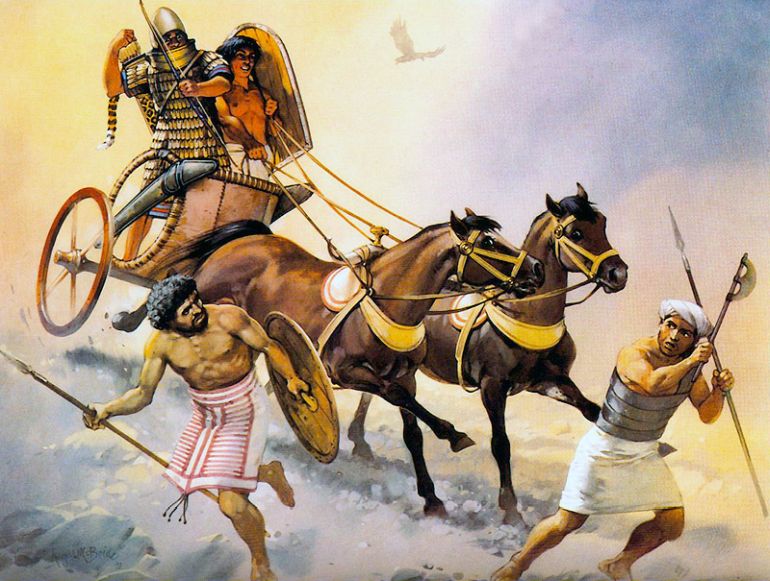

As a result, the Egyptians developed their somewhat unique chariot arm and its primary purpose was to defend their own troops from the aggressive forays and charging of the enemy chariots. Consequently, the design of the ancient Egyptian chariots rather reflected such a ‘defensive’ tactic. As a result, these platforms, drawn by two horses, tended to be lithe and light-weighted than their heavier Near Eastern counterparts.

In essence, the Egyptian chariots were designed to ‘react’ based on their better maneuverability and speed and thus proved to be more flexible when it came to variant battlefield roles, including even scouting ahead.

Furthermore, the sturdy frame that complemented the overall pliable design came in handy when navigating through the rough terrains of Egypt and Canaan. This in turn made them effective in deserts and hilly areas, thus alluding to the increasingly tactical nature of ancient Egyptian warfare.

As for the chariot riders of Egyptian history, they mostly comprised the highly trained nobility of the army, including the Egyptian king and his household. These elite warriors (armed with bow and arrow) were often superbly draped in full body armor – made of meticulously arranged metallic scales (scale armor).

The Runners Beside Chariots

Now given the trend of historical evolution and influence of neighboring military equipment (and tactics), over time the Egyptians began to provide better (and heavier) armor to their chariot troops, which in turn led to the adoption of hefty six-spoked wheels.

However the overall frame of the ancient Egyptian chariot continued to be nimble – and that allowed their horse-drawn war machines to maneuver effectively inside enemy lines, with zig-zag movements and surprise turns.

It should also be noted that the Egyptians employed a special class of infantry known as the chariot-runners who had multi-role capabilities on the battlefield. Lightly equipped with bows and javelins, these dynamic troops accompanied the chariots (behind their charge) to dispatch enemy charioteers and even rescue their own comrades who had crashed. Moreover, they were also expected to receive and absorb the charging momentum of the enemy chariots with their loose formations and potent projectiles.

The Allied Troops of the Egyptian Army

Like the military history of other ancient empires, Egyptians also had their fair share of mercenaries and auxiliary troops who came from different parts of Africa and Asia. One of the famous allied troops pertained to the Medjay, who were basically Nubian desert scouts of the ancient Egyptian military deployed as an elite paramilitary police force during the New Kingdom period.

Similarly, the empire was also known to recruit the remnants of the Sherden (one of the mysterious ‘Sea Peoples’), as can be surmised from one of the royal guard units of Ramesses II. Beyond such special units, the empire additionally employed auxiliary troops from their vassal states in Syria, Canaan, Nubia, and even Libya. These foreign contingents were bolstered by a motley of warriors (with presumably effective martial skills) who had been prisoners of war before their re-induction into the army.

The Ancient Egyptian Navy

While not much is known about the dedicated warships of the ancient Egyptians (unlike the later Greeks and Romans), historians have come across credible visual evidence that confirms the importance of the navy in the Egyptian army.

For example, the wall details of the Medinet Habu (Ramesses III’s mortuary temple) depict how the ‘native’ Egyptians under the pharaoh were victorious in a naval encounter over the ‘Sea Peoples’.

The naval vessels in question here were probably manned by trained marines armed with bows, slings, and even grappling hooks that were used to board the enemy ships (and sometimes even topple the ships themselves).

And judging by the size and scale of these marine crafts, it can be hypothesized that a standard ancient Egyptian war vessel of the New Kingdom era could possibly carry around 50 crew members, with 20 of them serving as oarsmen and the remaining fulfilling their role as fighters.

Sources: CEMML-Colorado State University / MetMuseum / AncientMilitary

Book References: New Kingdom Egypt (By Mark Healy) / War in Ancient Egypt: The New Kingdom (By Anthony J. Spalinger)

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork, or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "The Ancient Egyptian Soldiers of the New Kingdom"