Introduction

In our article about the Greek Gods, we mentioned how Greek mythology, like most ancient mythologies, was not compiled in a singular text. Rather most of the characters and creatures were inspired by the folkloric and oral traditions from both the Late Mycenaean Period (circa 11th century BC) and the later Heroic Age of Homer (possibly circa 9th century BC).

And historically, it was probably the poet Hesiod’s Theogony that compiled the first known origin story of Greek mythology, circa 700 BC. He was followed by various other Greek playwrights and poets (like Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides) who expanded upon and refashioned some elements of the vast Greek mythology.

Later Roman poets like Virgil and Ovid also played their part in adding and reorganizing some tales so as to give credence to the Roman side of affairs. Taking such literature into consideration here we present twenty-five remarkable monsters, dragons, and creatures you should know about from Greek mythology.

Contents

- Introduction

- List of Greek Mythological Creatures (in Alphabetical Order)

- Centaur

- Cerberus

- Cercopes

- Charybdis and Scylla

- Chimera

- Colchian Dragon

- Cyclopes

- Furies and Harpies

- Gigantes (or Giants)

- Griffin

- Hecatoncheires

- Hydra and Cancer

- Ladon

- Lamia (and Empusa)

- Medusa

- Minotaur

- Nemean Lion

- Pegasus

- Python

- Satyr

- Siren

- Sphinx

- Stymphalian Birds

- Typhon

- Honorable Mention – Phoenix

List of Greek Mythological Creatures (in Alphabetical Order)

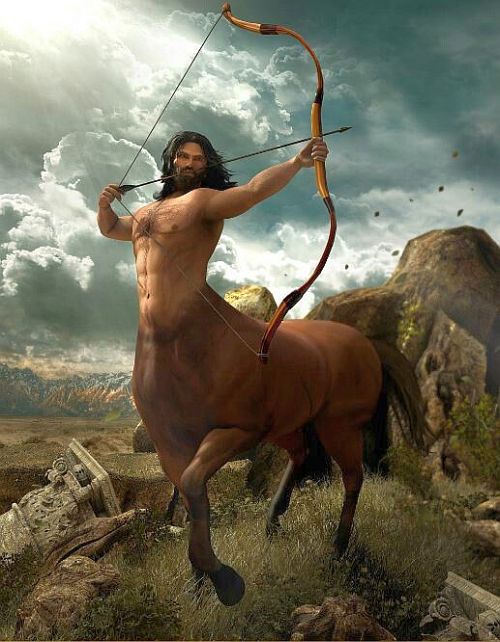

Centaur

Centaur (Kentauros or Ixionidae) is one of the staple mythical creatures contrived by Ancient Greeks, and their first representations are found in the paintings on hydriai (Greek vases). Depicted with a ‘hybrid‘ anatomy, with the upper body (torso) of a man and lower body (from the waist) of a horse, the Centaurs were projected as wild creatures who were prone to lawlessness and bestial urges.

They were believed to have resided in Mount Pelion and nearby forests of Magnesia (central Greece). In terms of one myth, the Centaurs were considered the children of Ixion, the king of Lapith tribes, who forced himself on (or seduced) Nephele, a cloud nymph shaped like Hera. Consequently, the Centaurs hated the Lapiths and waged a losing war on them – known as centauromachy.

Another version notes how the Centaurs were simply offsprings of Centaurus, a man who mated with the mares of Magnesia. In any case, these mythological creatures were possibly representations of the untamed side of nature. However, the exception was Chiron (or Cheiron), a wise and modest Centaur who capably tutored both demigods like Asclepius and heroes like Achilles.

Cerberus

Cerberus (or Kérberos) was the three-headed dog that stood guard at the very gates of the Underworld – the realm of Hades. Often depicted as one of the terrifying monsters of Greek mythology, the very name Kérberos is possibly derived from the Greek words kêr and erebos – referring to a “Death-Daemon of the Dark”. To that end, in addition to being a three-headed dog, Cerberus was said to have a tail of a serpent, a mane of snakes, and claws of lions.

In most Greek myths, Cerberus belonged to a family of mythical monsters. According to poet Hesiod’s Theogony (circa 700 BC), Cerberus was the second offspring of Typhon (the father of monsters – discussed later) and Echidna. The other siblings of the three-headed dog included various mythical monsters like Hydra, Chimera, Sphinx, and the Nemean Lion (all discussed later).

Interestingly enough, in spite of his monstrous appearance and grave status as the guard of the underworld, Cerberus tended to retain some of his simple dog-like nature. For example, in Virgil’s Aeneid, Cerberus was deceived by the honey cakes of Sybil that put him to sleep, which allowed Aeneas’ foray into the underworld. Similarly, Cerberus was also tamed by the music of Orpheus, which allowed the hero to foray into the guarded realm of Hades to seek his beloved.

However, the most famous myth involving Cerberus possibly pertains to the last of the Twelve Labors of Hercules. In this story, the hero Hercules (or Heracles) managed to beat the monstrous guard dog by putting the latter’s head into a stranglehold (other myths mention how Hercules used his club or a large stone). Consequently, Cerberus passed out and was bound by adamant (archaic diamond) chains and unceremoniously dragged to the surface.

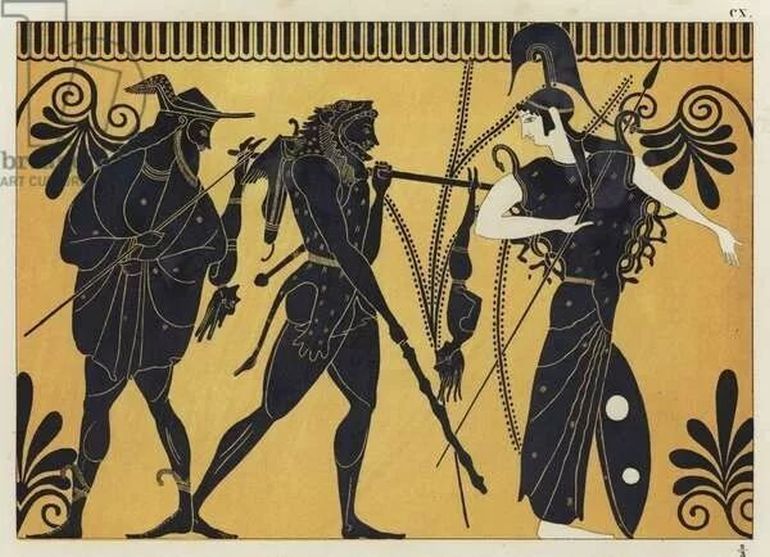

Cercopes

Relatively obscure when it comes to popular aspects of Greek mythology, Cercopes (or Kerkopes) were designated as mischievous monkey-like mythical beings that hailed from the forests of Thermopylae or Euboea. They were said to be the offspring of Titan Okeanos (Oceanus) and mortal Theia.

In most myths, the Cercopes are presented as knavish folks who are prone to stealing and cheating. For example, in the Bibliotheca of Pseudo-Apollodorus, the two brothers (of Cercopes background) stole the weapons of Hercules in Lydia. After discovering the foul deed, Hercules tied them to a shoulder pole with their faces pointing downwards.

However, the Cercopes laughed and made jokes at the sight of Hercules’ dark-tanned rear. The amused Hercules ultimately sets the duo free (in some stories, at the bidding of their mother Theia). Yet in another myth, the Cercopes brothers were turned into actual monkeys (or stones) by Zeus when the duo ran afoul of the Olympian king of Greek gods.

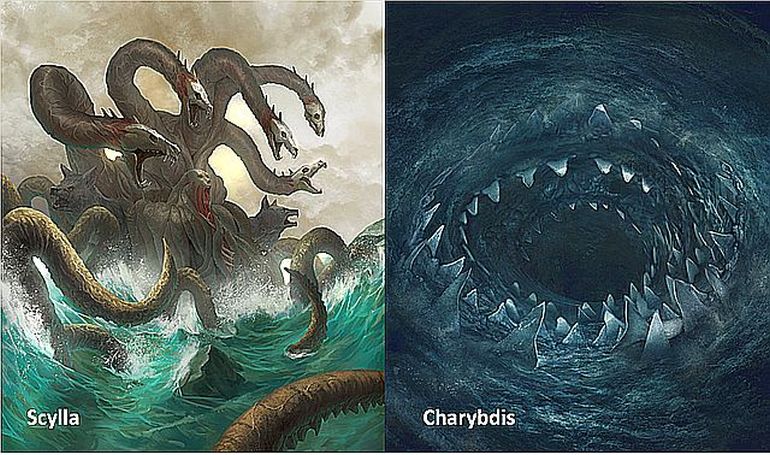

Charybdis and Scylla

Charybdis was described as a sea monster that remained hidden in the Strait of Messina, later equated to (or rationalized as) the whirlpool of the area. In Greek mythology, Charybdis was the offspring of the sea god Poseidon and Gaia (or Gaea, the Earth goddess).

In the mythical narrative, Charybdis was originally a nymph who was tasked with the ebb and flow of the daily tides around the world. But she was later cursed by Zeus and turned into a monster. One version of the story mentions how Charybdis was overzealous in serving her own father Poseidon, which resulted in the flooding of large swathes of land. Zeus punished the deed by turning her into a merciless monster.

In another version of the myth, Charybdis stole and ate the sheep of Hercules. Thus the angered Zeus transformed her into a whirlpool-like monster with a huge mouth and sharp teeth (or imprisoned her below sea rocks which resulted in periodic whirlpools). Suffice it to say, the strait was perceived as a dangerous route by ancient sailors of Magna Graecia.

Talking of the Strait of Messina, in Greek mythology, another sea monster Scylla was said to reside on the other side (Sicily) of this water channel. And interestingly enough, much like Charybdis, Scylla was initially also a beautiful woman (or nymph). However, the jealous witch Circe poisoned the pool of the nymph – which grotesquely transformed Scylla into a monster with six heads (with shark-like teeth) on snake-like necks, a waist ringed with heads of dogs, twelve tentacle-like legs, and a cat’s tail.

Psychologically (and physically) afflicted by her transformation, Scylla was said to have uncontrollable rage for men – so much so that she vociferously attacked sailors and even ate them alive. Such was the gruesome fate reserved for six crew members of hero Odysseus when their ship passed through the narrow channel.

Chimera

Chimera (or Khimaira) was the epitome of mythological monsters of Ancient Greece in the sense that it was a combination of many fabulous animals. Translated as ‘she-goat’ or simply ‘monster’, the bizarre fire-breathing Chimera had the head and body of a lion, an additional head of a goat, udders of a she-goat, and the tail of a serpent.

In most tales of Greek mythology, the Chimera, like her sibling Cerberus, was the female offspring of Typhon and Echidna. And talking of myths, the fearsome monster was said to have roamed and ravaged the countryside of ancient Lykia (Lycia) in Anatolia. However, her loathsome romp was cut short by the hero Bellerophon, who slew the monster from the back of the winged horse Pegasus (discussed later).

In some tales, Bellerophon killed the three-headed monster Chimera by plunging his lead-laced lance into the creature’s fiery throat. Other legends talk about how the hero utilized the flight of his magical horse and shot arrows from above into the hide of Chimera. As for symbology, Chimera was probably a metaphorical representation of the various permanent methane gas vents that are still found in the Lycian Way, in modern-day southwestern Turkey.

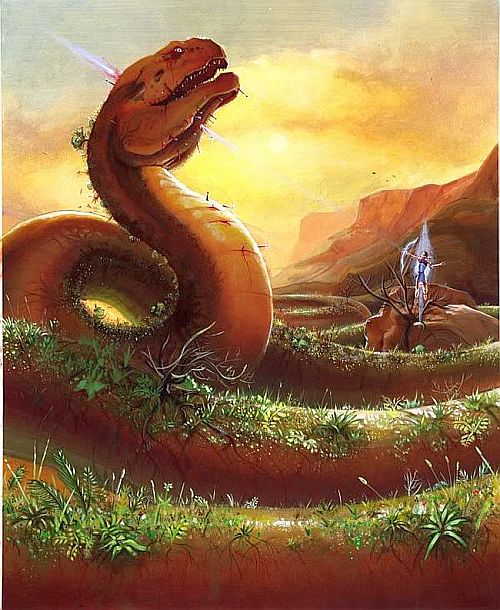

Colchian Dragon

In Greek mythology, the Colchian Dragon (or Drakon Kholkikos) was supposedly born from Gaia (Earth) when the blood of the monstrous Typhon (discussed later) was spilled on it by Zeus, the King of Olympian Gods. The dragon was then ‘posted’ as the guardian of the Golden Fleece inside the sacred grove of Ares (the God of War) in Colchis (present-day Georgia). The fleece belonged to the winged ram Cyrsomallos who was sacrificed to Zeus.

The Golden Fleece was the object of a quest undertaken by Jason and the Argonauts. However, given its monstrous pedigree, the Colchian Dragon, longer than a trireme (50-oared ship), had the supernatural ability of not needing to sleep or even blink its eyes.

As a solution to end the beast’s watchfulness, the witch Medea knocked the dragon out with a potent brew of drugs (in some myths, it was Orpheus who lulled the dragon to sleep with his music). Consequently, the unconscious (or sleeping) dragon allowed Jason to claim the fleece.

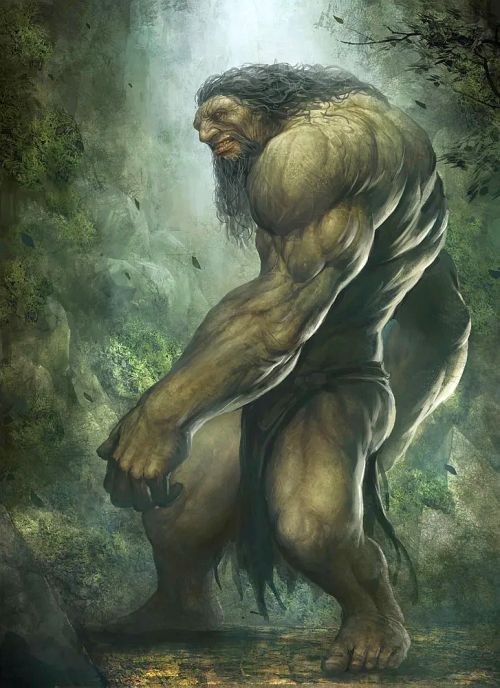

Cyclopes

Cyclopes (or Kyklopes), literally meaning ’round-eyed’ (or ‘circle-eyed’), were considered an entire race of strong mythical creatures or one-eyed giants who were even older than the Olympian Gods. In Greek mythology of Hesiod’s Theogony, they were the male offsprings of Ouranos (or Uranus – the Sky god) and Gaia (the Earth goddess) – the primordial deities of ancient Greeks.

Hesiod further elaborated how the Cyclopes initially helped Kronos, the youngest son of Ouranos, in overthrowing their father – because Ouranos trapped (‘devoured’) many of his children inside Gaia’s womb. And while Kronos and his siblings (known as the Titans) successfully deposed Ouranos, the Cyclopes were unceremoniously imprisoned in Tartarus – the deepest part of the Underworld (the Greek version of hell)

The next ‘batch’ of Greek Gods (known as Olympians), headed by Zeus (son of Kronos), in turn, overthrew Kronos from his throne. During this power struggle for the cosmos (Titanomachy) the Cyclopes were freed from their prisons. And in gratitude, they crafted the thunderbolts of Zeus and the trident of Poseidon. In essence, the Cyclopes (singular Cyclops) were perceived as a powerful albeit violent race who were experts in metallurgy and even wall-building.

However, in Homer’s Odyssey, the Cyclopes are presented as uncouth merciless monsters of Greek mythology who ate humans by bashing their heads. One such Cyclops Polyphemus, the son of Poseidon (instead of Ouranos) was blinded by the crafty hero Odysseus. In another tale from Theogony, Apollo vengefully slew a trio of Cyclopes. They were wrongfully accused of the murder of his son Asclepius, the god of medicine.

Furies and Harpies

Erinyes (also called Furies) were perceived as female entities (or spirits) of vengeance in Greek mythology. Mythically older than the Olympian Greek Gods, these chaotic beasts were invoked to punish the breaking of an oath or the natural order.

Simply put, they were viewed as violent agents of retribution who were brought forth from their chthonic (underworld) realm when the victim called for a severe curse on the offender or criminal. The origins of the Erinyes, as mentioned in Theogony, also ascribe to the aspect of reprisal – since these female monsters were born when the rebellious Titan Kronos castrated the genitalia of his father Ouranos, the Sky God.

In English, ‘fury’ pertains to intense rage or extreme violence. The origin of this word is ultimately derived from ‘Erinyes‘, which was adopted as ‘Furia’ in Latin. Similarly, ‘harping’ or ‘to harp’ means to ‘talk or write persistently and tediously on a particular subject.’ This word was derived from Harpies. To that end, the Harpy was a mythical creature who carried and tortured people on their way to Tartarus.

Described as half woman and half bird, these female monsters even helped the Furies (as servants) to dole out judgment on the criminals. As for their odd physical characteristics, the Harpies were initially depicted as large birds with faces of beautiful women. However, over time, they became unsightly – evident from the writings of both Virgil and Ovid. Some researchers have theorized that Harpies, as flying creatures, were simply personifications of destructive wind or gales.

Gigantes (or Giants)

In Greek mythology, Gigantes (or Giants) were the children (or creations) of Gaia, the Earth goddess. Hesiod’s Theogony mentioned how the Gigantes (implying ‘earth-born’) were possibly conceived by Gaia, but they only sprung up from the earth after the blood of Ouranos was spilled during his castration by Kronos.

Quite intriguingly, in most Greek myths and vases, the Gigantes are not portrayed as tall creatures; rather they are depicted as strong and resilient beings dressed much like conventional Greek hoplites. For example, Hesiod even added how the Giants were born with their gleaming armor while holding stout spears.

In terms of history, the Gigantes were possibly confused by later authors (like Ovid) with other Greek mythical beings like the Titans and the Hecatoncheires (discussed later). Such complex accounts have put forth the Gigantes as unruly, arrogant, and even violent (but mighty) opponents of the Olympian Gods headed by Zeus. Later portrayals of the Giants (after circa 380 BC) also transformed them into monsters with serpent legs.

Griffin

Although the Griffin does not have its origins in Greek mythology, the creature (Gryps or Gryphos in Greek) depicted by ancient Greeks was fairly uniform in its appearance – a regal mythical beast with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle.

In some Greek myths, the Griffins were considered an entire tribe of mythical creatures who zealously guarded the gold mines in the distant mountains of Scythia. This made them the enemies of the neighboring one-eyed tribes of Arimaspians (not to be confused with Cyclopes) who wanted the riches for themselves.

Interestingly, the Griffins were said to lay agates instead of eggs. Over time, these proud mythical beasts were associated with the Sun, with some imagery depicting them as the animals who guided the chariot of the Sun. Griffins are also described as ‘hounds’ of Zeus, and beasts of Nemesis (the goddess of retribution) and Apollo.

Hecatoncheires

Hecatoncheires(meaning hundred-handed ones) refers to the collective name given to three monsters (Briareus, Cottus, and Gyges) who were the children of Gaia (Earth) and Uranus (Sky). And, they were not only known for their frightful enormity but also for their ghastly arrangement of hundred arms and fifty heads.

Even the powerful Uranus was so taken aback by their strength (and apparent ugliness) that he decided to push them back into Gaia’s womb. On failing to do so, they were subsequently banished to the underworld of Tartarus – thus sharing a similar fate to that of the Cyclopes.

However, the Hecatoncheires more than made up for their revolting appearance when they helped the Olympian Greek gods in their fight against the Titans, who were also the offspring of Gaia and Uranus. As legend has it, the multi-limbed monsters had the better of their siblings partly aided by their capability to launch a multitude of rocks at their opponents. Briareus, the Hecatoncheires, even went on to serve as the bodyguard of mighty Zeus.

Hydra and Cancer

Possibly the most vicious offspring of Typhon and Echidna, the Hydra (Hydra Lernaia or Lernean Hydra) was depicted as one of the massive serpentine monsters in Greek mythology. Having multiple heads with regenerative quality, along with toxic breath and blood, the Hydra was said to have its lair at Lake Lerna, which was believed to be the point of entry to the underworld.

Like others before it, the most famous myth of the Hydra relates to one of the labors of Hercules. In this ancient story, the hero confronted the monster in a bid to kill it near the noxious-fume-filled swamp of Lerna. Hercules used his sword (or sickle) to cut off the head of the serpent, but the decapitation of one head led to the emergence of two ‘new’ heads.

As mentioned in Bibliotheca, the confounded Greek hero then called upon his trusty nephew Iolaus. And so when Hercules proceeded to cut off the heads of Hydra, the diligent Iolaus used a firebrand to burn the severed section of the necks. This creative method cauterized the ‘open wounds’ – thus blocking the emergence of newer heads.

In a desperate attempt to free the Hydra, finally, a giant crab Karkinos (or Cancer) came to the aid (possibly sent by Hera). But it was duly crushed under the mighty feet of Hercules. Hercules then dipped his arrows into the toxic blood of the dead serpent, which imbued them with virulent potency. And after the demise of the two mythical monsters, the upset Hera placed them as constellations Hydra and Cancer in the sky.

As for history, the imagery of Hydra dates back to at least 700 BC, with six heads. Interestingly, different ancient authors put forth a varying number of heads for the monster. For example, Alcaeus (circa 600 BC) endowed it with nine heads, while Simonides, writing a century later, increased the number to a whopping fifty. A few even suggested a single head for Hydra.

Ladon

Ladon (also called the Hesperian Dragon) was the dragon that zealously guarded the Golden Apples in the Garden of Hesperides (Hesperides were the nymphs of the sunset). And like many other famous monsters of Greek mythology, Ladon was confined to a particular geographical area. The area in question here pertains to the fabled location of the Garden of Hesperides – which was believed to be in the furthest west of the known world.

Unfortunately for Ladon, one of the Labors of Hercules dictated that he retrieve the Golden Apples from this legendary garden. And thus the most famous of all the Greek heroes crossed the Libyan desert and located the verdant complex by the edge of Okeanos (Oceanus) – the great river that encircled the world. Hercules then proceeded to unceremoniously slay the dragon with poisoned arrows.

In another version of the story, Hercules never killed Ladon. Instead, he tricked Atlas (the Titan father of Hesperides nymphs), who retrieved the Golden Apples for the hero. As for depiction, Ladon was portrayed as a serpentine monster that encircled the tree in order to guard his treasure. Aristophanes (‘the father of comedy’) however mentioned how Ladon had multiple heads, which sometimes leads to his representation with hundred dragon heads.

Lamia (and Empusa)

Lamia was the cursed monster (or demonic entity) who grimly feasted on children and even unborn fetuses. In Greek mythology, she was originally a queen from Libya of ‘unsurpassed beauty’ who caught the eyes of Zeus, the King of Olympian Gods. Unfortunately, for Lamia, she also incurred the wrath of the upset Hera (wife of Zeus) – who snatched away all of Lamia’s own children.

The grisly myths also mention how the jealous Hera made Lamia kill her own children. Thus over the passage of time, the Libyan queen became mad with grief, so much so that she even tore off her own eyes. Ultimately, the torturous path transformed her into a monster with an appetite for children and human blood. The mental affliction also contributed to a ghastly physical change, as Lamia became more bestial in appearance.

In some stories, it was Zeus who gave her the ‘power’ (of shapeshifting and prophecy) to take revenge by devouring the children of others. And thus Lamia became a nocturnal demon-like monster who preyed on pregnant mothers and small children. Historically, she also became associated with the Empusae (or Lamiae) – the vampiric females who fed on the blood of young men.

Medusa

Medusa (or Gorgo), one of the famous female monsters from ancient Greek mythology, was often depicted as a ghastly woman with venomous snakes in place of hair. Her dreadful stare was supposed to turn onlookers into stones. Interestingly, in mythical narratives, Medusa was actually one of the Gorgons – three sisters who were the daughters of primordial gods Phorcys and Ceto.

Some stories (especially Roman ones), like that of Ovid, mention how Medusa was born as a beautiful woman, unlike her monstrous sisters. However, she suffered the worst fate among the three after being cursed by Athena (or Minerva – her Roman counterpart). One version narrates how the punishment was given to Medusa because she engaged in sexual activities with Poseidon (or Neptune, the Sea God) inside Athena’s temple.

The curse transformed her into a monster with snakes on her head, bronze hands, and golden wings. Some poets even mentioned that Medusa had a hideous lolling tongue and boar-like tusk. However, arguably the most famous myth relates to how Perseus, the Greek hero, went on to decapitate Medusa and use her head as a weapon (for turning his enemies into stone).

The head was later given to Athena, to be placed on her mighty shield. And such was the abominable power of Medusa that even her spilled blood led to the birth of Amphisbaena, a horned dragon with a snake tail. Her severed neck also gave birth to Pegasus (discussed later), possibly because Medusa was pregnant at the time of her death.

Quite intriguingly, the historical imagery of Medusa and the Gorgons was found in the 11th century BC. This has led some scholars to believe that the myth of Medusa possibly represented an actual traumatic event (like invasion) after the collapse of Bronze Age Mycenae.

Minotaur

Popularly depicted as a hybrid monster comprising half bull and half man, the word Minotaur is derived from Μίνως or ‘Minos’ and the noun ταύρος or ‘bull’, thereby meaning the ‘bull of Minos’. And in Greek mythology, the tale of the Minotaur is quite a sordid one.

To that end, Minotaur was conceived from the elicit union of a white bull and Queen Pasiphae (the wife of King Minos of Crete). The ‘unnatural’ passion of the queen was the result of a curse unleashed by Poseidon (and Aphrodite). Thus the bull-headed monster was born, who was originally given the name of Asterion, meaning ‘star’; or Asterius – ‘starry one.

But over time, as it grew in strength and ferocity, the Minotaur, having no natural source of sustenance, began to devour unsuspecting humans for its nourishment. Consequently, to hide his shame and protect his citizens, King Minos constructed the Labyrinth beneath his Palace at Knossos – and this prison/lair held the bloodthirsty Minotaur.

The beast, however, was further satiated with the sacrifice of seven Athenian boys and girls – who were sent to Crete as human tribute every seven years (other versions mention every year to every nine-year period). And in a bid to put an end to this grisly practice, it was Theseus (son of Athenian king Aegeus), who, aided by Princess Ariadne (daughter of Minos), delved inside the Labyrinth and slayed the Minotaur.

Nemean Lion

Yet another monstrous offspring of Typhon (or Orthus – the two-headed dog) and Echidna, the Nemean Lion was perceived as a savagely strong beast that boasted of a golden fur (or hide) that was impervious to any mortal-made weapon. Furthermore, the mythical monster had diabolically sharp claws that could pierce any armor made by man.

In Greek mythology, the Nemean Lion terrorized the local population of Nemea (from where it gets its name). Incredibly enough, the gigantic lion was supposedly sent to the hills of Nemea by Hera, the Queen of Olympian Gods. However, Hercules’ first labor required him to slay the beast and return to the village within 30 days.

The unknowing hero started out by shooting arrows into the thigh of the terrifying monster, but they flimsily bounced off the hide. Hercules then demonstrated his own supernatural strength by seizing the neck of the creature and choking it to death.

Subsequently, he wore the impenetrable lion hide as his own armor – which serves as a visual motif for Hercules in both classical and popular art. It was said that the remorseful Hera then placed the lion in the constellation Leo.

Pegasus

As mentioned earlier in the article (see entry Medusa), Pegasus, along with his brother Chryasor, sprang forth from the severed neck of the pregnant Medusa when she was decapitated by the hero Perseus. Usually depicted as a winged horse, Pegasus was fathered by Poseidon, the mighty God of Seas in Greek Mythology.

This connection with Poseidon goes deeper in the myths, as Pegasus was given to another one of his sons – the hero Bellerophon. Bellerophon, in turn, killed the monster Chimera by using the flight of his winged companion (and ‘technically’ half-brother). However, after a few adventures, Pegasus parted ways with the hero and reached Mount Olympus – the very abode of many Greek Gods. Here the winged horse served both Eos (who brought forth dawn) and Zeus.

Now Pegasus as a mythical horse shouldn’t be confused with Balius and Xanthus, two immortal horses owned by the hero Achilles during the Trojan War. Other horses in Classical mythology include the Mares of Thrace – a herd of four man-eating horses owned by Diomedes.

Python

Python was depicted as a huge serpent (or serpent-like dragon) that was born out of the slime (or mud) from the receding floods in Delphi. In essence, this made it the female offspring of Gaia, the Earth goddess. Python was described as being so humongous that her gargantuan coils stretched around the entire site of the Delphi oracle – thus ably protecting her mother and the Delphic precinct.

However, it was the Olympian deity of light Apollo who slew the mythical serpent with his weapon of choice – the bow and hundred arrows (gifted by Hephaestus, the god of metallurgy). Subsequently, Apollo also took over the stronghold of Delphi and grandly refurbished it to his own tastes. Symbolically, this suggested the passing of the ownership (or patron) of temples and oracles from the older primordial gods (like Gaia) to the Olympian gods (like Apollo).

In some abstruse narratives of ancient Greek mythology, the Python was also counted as one of the pets of Hera (wife of Zeus), and that gave her the ‘privilege’ to cause harm and destruction to the surrounding lands, without getting punished.

Satyr

In Greek mythology, Satyrs (or Satyroi) were considered wild creatures who indulged in excessive behavioral patterns, including lustful activities and exorbitant consumption of wine. Often described as males with dense hair, fierce beards, and legs of goat (or part beast, like horse’s ears and ears), Satyrs were mostly associated with the Greek god Dionysus.

Residing in forests to pursue their immoderate lifestyles, the Satyrs were lewd and mischievous. However, on the other hand, they were also industrious and skillful in music – aspects that were made use of by Dionysus himself, when he employed such creatures for winemaking.

Interestingly enough, the foster father of the god Dionysus was a Satyr by the name of Silenos (or Silenus), who was also believed to be the father of all Satyrs. But as opposed to the uncivilized nature of his wild descendants, Silenos was a wise and knowledgeable tutor.

In terms of history, Satyrs were possibly symbolic representations (or warning markers) of unrestrained lifestyles or revelry. Quite intriguingly, in ancient Greek theaters, there were actors who dressed up as satyrs for the chorus. The god Pan, with his goat horns and legs, may have also been associated with these creatures.

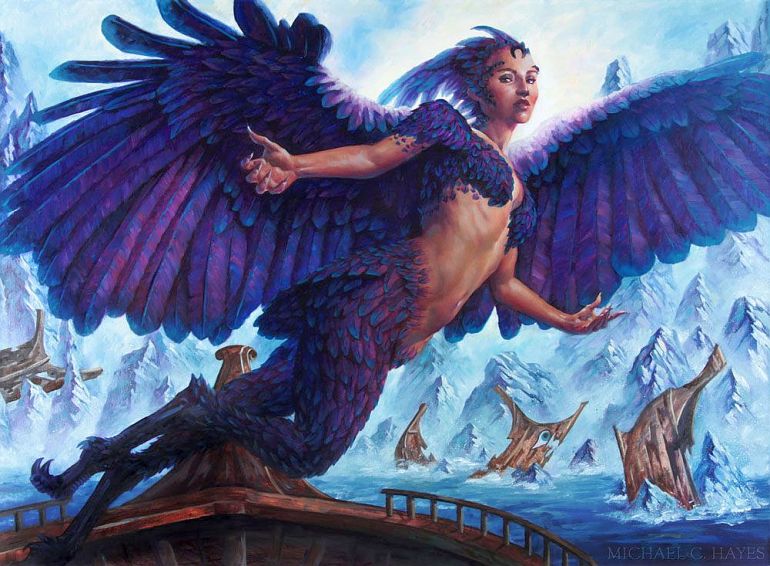

Siren

Contrary to popular depictions, Sirens (or Seirênes) were not mermaid-like creatures in Greek mythology. Instead, they have been described as having the anatomy of a half-woman (the upper body) and half-bird (the lower body). Often represented as beautiful women with incredibly alluring voices that called upon the passing sailors to their destruction, the Sirens (two or three in number) were said to be the daughters of Achelous (a river god) or Phorcys (a primordial sea god).

In most mythical narratives, the Sirens were initially the handmaidens of Persephone, the daughter of Demeter – the Olympian goddess of the harvest. Now in some legends, they were given wings by Demeter to seek out Persephone after she was ‘kidnapped’ by Hades to the underworld. In other myths, the Sirens were cursed with wings and inhuman features after they failed to find Persephone.

However, the most popular myth relates to how the Sirens, perched on rocky cliffs (possibly at Sirenuse, Italy), enchanted unsuspecting sailors with their beguiling voices – to finally kill the innocent men. In Odyssey, the hero Odysseus ‘bypassed’ the danger by instructing his crew members to block their ears with beeswax, while he himself was tied to the mast. The cursed Sirens, upon failing in their objective, supposedly fell off the cliffs to their deaths.

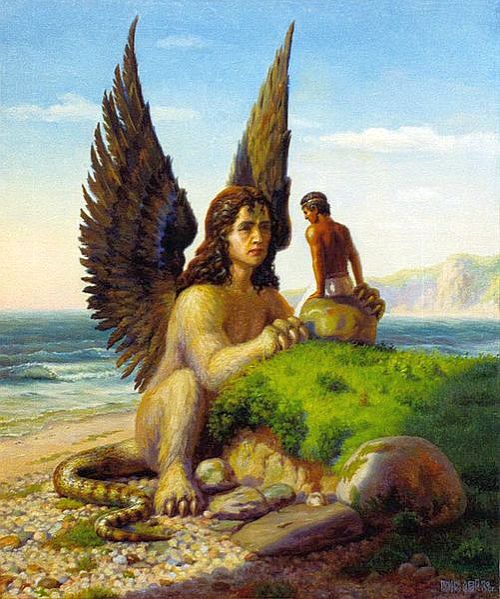

Sphinx

Much like the earlier mentioned Griffin, the Sphinx was not exactly an invention of Greek mythology, with the most famous example relating to the Egyptian mythical being. However, in the Greek version, the Sphinx was depicted as a rather treacherous and merciless monster with the head of a female human and the body of a lion. Additionally, she had the wings of an eagle (unlike her Egyptian counterpart) and the tail of a snake.

In the most famous myth, Sphinx was said to have been an offspring of the serpent Echidna, which made her the sibling of monsters like Cerberus and Chimera. The story further elaborates on how the Sphinx was sent to the ancient Greek city of Thebes as a punishment by the gods, relating to a past crime perpetrated by the city dwellers.

Thus the task of the Sphinx was to guard the city gates and ask all travelers a particular riddle. And if they failed to answer it, they were eaten alive by the harsh monster. However, the hero Oedipus successfully answered the riddle, and subsequently, the Sphinx plunged to her death in despair. Historically, this association with death was often mirrored by the Sphinx-engraved stelae on the tombs of young men.

Stymphalian Birds

Often described as a flock of man-eating birds, the Stymphalian Birds were said to have bronze beaks and sharp metallic feathers (along with toxic dung) that could be used against their unfortunate victims. In Greek mythology, these voracious flying monsters were apparently created by Ares (the God of War) or were the pets of Artemis (the Goddess of Hunt). These birds escaped the wolves to nest by Lake Stymphalia in Arcadia – where they multiplied and terrorized the local populace.

As for their most popular myth, it was once again tied to the Labors of Hercules. For his sixth labor (which required him to slay the Stymphalian Birds), the Greek hero approached the lake, but the marshy land couldn’t bear his enormous weight. However, Goddess Athena intervened and presented Hercules with a krotala, a rattle that scared the birds into flight.

And once the monstrous birds took their flight from the inaccessible marshy area, Hercules was able to shoot them with the poisoned arrows dipped in the noxious blood of Hydra (discussed earlier). According to some stories, most of the Stymphalian Birds were killed, while few others escaped to the Black Sea – where they were encountered by the Argonauts.

Typhon

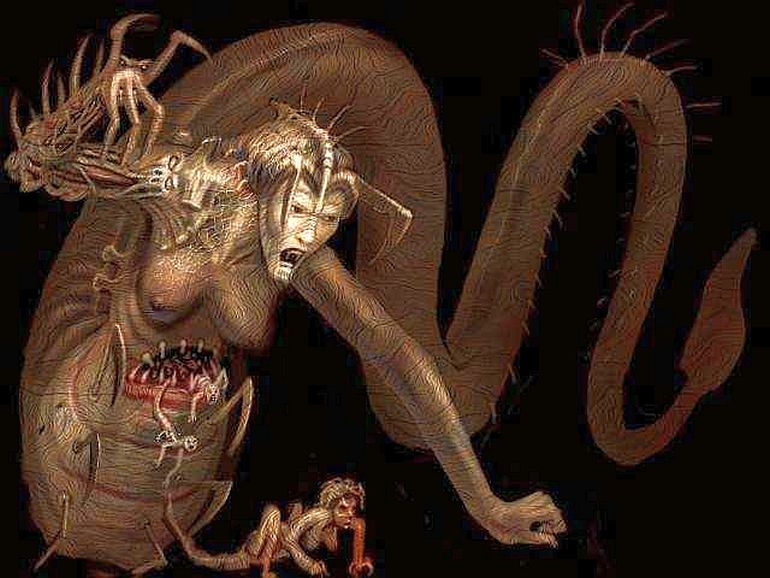

Typhon (Typhoeus or Typhaon) was depicted as the humongous serpentine monster in Greek mythology. In Theogony, he was represented as the monstrous offspring of Gaia (the Earth) and Tartarus (the harrowing abyss of the Underworld). In the Bibliotheca, it is further mentioned how Typhon was birthed out of spite by Gaia when the Olympians (under Zeus) drove off her other sons (the Titans and the Giants) to establish divine rule over the cosmos.

Given his association with violence and vengeance, a hundred dragon heads erupted from the neck and shoulders of Typhon – as the monster besieged the very heaven of the Olympian Gods. The Greek tragedian Aeschylus (circa 5th century BC) mentioned how Typhon could even breathe fire from his innumerable snake heads. But the immensely powerful bestial creature was defeated by Zeus and subsequently imprisoned inside the lowest pit of the Underworld.

As for the aspects of Typhon, it was widely believed that he was the storm-giant who unleashed the violent gales from the Underworld (which establishes the relationship with the word Typhoon). In some stories, he is also (possibly mistakenly) portrayed as the volcano-giant Enceladus, who was defeated by Athena and banished underneath Mount Etna in Sicily.

In terms of the mythical narrative, Typhon is also the father of a host of other monstrous creatures, including Cerberus, Hydra, Chimera, Sphinx, and the Nemean Lion. His mate was the female monster Echidna who had the strange anatomy of a half-woman and half-snake.

Honorable Mention – Phoenix

Popularly identified as a mythical firebird that could resurrect from its own ashes, the origins of the Phoenix are pretty obscure when it comes to Greek mythology. According to one hypothesis, the Greek version of Phoenix was possibly inspired by Bennu, the self-created bird god of ancient Egypt. Other theories have alluded to how the Egyptian myth was possibly ‘concocted’ after the prevalence of Classical folklore.

Anyhow, in most myths, the Phoenix was said to be a magical bird with vibrant plumage that originated in either India or Arabia. Herodotus mentioned how only a single Phoenix is alive at a time for a lifespan of 500 years. By the end of its lifecycle, the mythical creature voluntarily ignites itself in a nest filled with incense – and from the ashes, a new Phoenix rises anew.

In any case, given its complex history and mythology, the Phoenix has been depicted in various ways. For example, Herodotus talked about the firebird that looked like an eagle but with red and gold feathers. The Romans incorporated even more colors into the representation, thus making the Phoenix akin to a peacock.

And the later Christians also adopted the symbolism of rebirth associated with the Phoenix with the allegorical resurrection of Christ. They further endowed the creature with the hue of rich Phoenician purple (a very expensive red-purple dye extracted from the murex shellfish). Such representations also made their way into the medieval bestiaries of Europe, with the famous example pertaining to the Aberdeen Bestiary of the 12th century.

Other Sources: Bibliotheca / Metamorphoses

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork, or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "Monsters, Dragons, and Creatures of Greek Mythology"