Popular notions tend to group the later Eastern Roman realm, or more specifically the Byzantine Empire, as a strictly medieval entity that encompassed Greece, the surrounding Balkans, and the Anatolian landmass. But if we take the impartial route that is ‘bereft’ of prejudiced medieval European politics and chronicling, the Byzantine Empire was the continuation (and even represented endurance) of the Roman legacy, so much so that most of its citizens called their realm Basileia tôn Rhōmaiōn – the Roman Empire.

To that end, the very term ‘Byzantine’ in spite of its popularity, is a misleading word. So without further ado, let us delve into the history, organization, and evolution of the early medieval (Eastern Roman) Byzantine army, from the 7th to 11th century.

Note* – In spite of its slightly fallacious nature, we will continue to use the term ‘Byzantine’ instead of ‘Eastern Roman’ in the following article, for the sake of clarity (for most readers).

Contents

Introduction – The Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantine Empire?

As we mentioned before, the term ‘Byzantine’, as opposed to Eastern Roman, is rather a medieval invention that sort of takes an uncomplimentary route. This was partially based on the prejudices of medieval chroniclers. In fact, to that end, the word ‘Byzantine’ is rather deprecatory even in our modern world, with its association often made to “deviousness or underhand procedure” (Oxford Dictionary).

In essence, such biased views were often concocted by the contemporaries of the Eastern Roman Empire, who perceived the political scope and ploys favored by the Romans as being overly complicated and labyrinthine.

However, as historian Ian Heath wrote (in Byzantine Armies 886-1118 AD) – in spite of such misunderstood labeling and anachronistic slanders, the Byzantine army of 10th century AD was possibly the “best-organized, best-trained, best-equipped and highest-paid in the known world”.

Simply put, the Byzantine army from this particular age was the closest to a professional force that served any known medieval realm. And this scope of professionalism was rather reinforced by the favorable economic might of the empire, strengthened by an organized military system (that was different from their ancient predecessors – the Roman legions), and well-defined logistical support.

Organization of the Byzantine Army

Bandon – The Basic Unit of the Eastern Roman Army

The military manual of Strategicon (or Strategikon, Greek: Στρατηγικόν) written by Eastern Roman Emperor Maurice in the late 6th century dealt with the general military strategies of the early Byzantine army. Unsurprisingly, the renowned Tactica military treatise written by or on behalf of Byzantine Emperor Leo VI the Wise (circa early 10th century AD), drew heavily from the Strategikon.

And both of these manuals talked about the basic military unit of bandon (or tagmata as mentioned in Strategicon), a word itself derived from the Germanic ‘banner’. This alludes to the foreign influence in the Byzantine army during the early medieval period.

Now it should be noted that the number of troops within each bandon varied in accordance with the available manpower from the Byzantine Empire, which took into account the injured and the invalidated. In any case, on the theoretical level, by Emperor Leo’s time, a bandon possibly accounted for 256 men for infantrymen (comprising sixteen lochaghiai) and 300 men for cavalry units (comprising six allaghia of 50 men each) – and each one was commanded by a komes or count.

Interestingly enough, the Byzantine army did make use of ‘mixed’ divisions of soldiers within each bandon, with ratios of 3:1 to 7:3 when it came to spearmen (skutatoi) and archers, thus suggesting advanced tactical deployments on the battlefields. The banda (plural of bandon) was also used as the standard for determining bigger divisions, like moirai and turmai.

To that end, a moira often contained variable numbers of banda, oscillating between 2 to 5 – possibly accounting for around 1,000 troops in the 10th century AD (as opposed to the norm of 2,000 men for each moirai in the 6th century AD). The turma, on the hand, comprised around three moirai, thus amounting to around 3,000 men.

The Themata or Provincial Armies

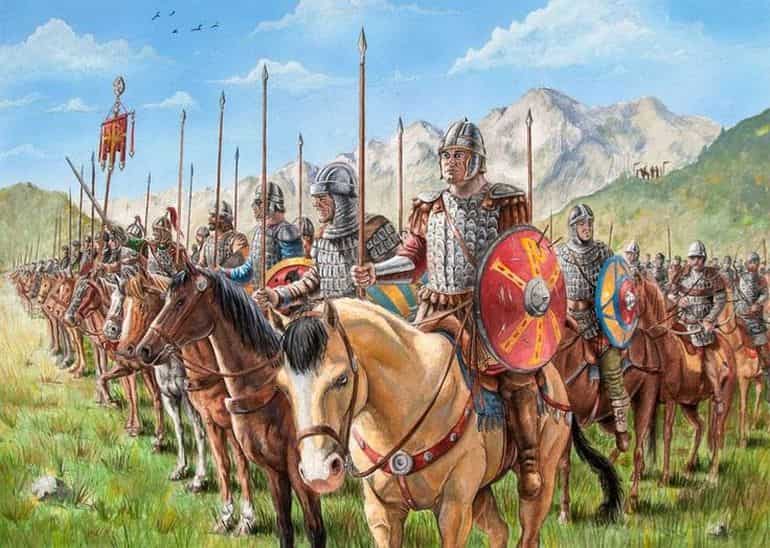

The weight of the entire Byzantine military system from the 7th century to the early 11th century AD was dependent on the Themata (or Themes) system – an administrative network of provincial forces that guarded the Byzantine Empire (more or less across Anatolia).

Partly inspired by the provincial system set in place by Constantine the Great, the Themata – as we know it today, was possibly established during the reign of Constans II, as opposed to the popular notion associated with Emperor Heraclius. In any case, the rise of this defensive force, initially based on the provinces of Anatolia, was probably fueled by the incursions of the Arabs on the eastern frontiers of the Empire.

Now each of these theme armies was commanded by a military governor known as the strategos (or general), who also boasted his personal retinue of heavily armed troops known as the spatharioi (spatha or sword ‘bearers’). And on occasions, some of these retinues rose to hundreds of men, as was in the case of the Thema Thrakēsiōn, whose strategos had a retinue of two banda – approximately 600 men.

The military governor was additionally assisted by other high-ranking officials who took responsibility for the province’s revenues, taxation, and most importantly payments for the provincial army.

However, the core member of the Themata pertained to the regular provincial troop, who usually belonged to the farmer-soldier background. These freemen were offered plots of agricultural land (often hereditary) in return for their mounted (in theory) military service. This setup sort of bridged the gap between the foederati of the Late Roman army and the rising feudal tendencies in erstwhile Europe.

But the size of such plots tended to be smaller than the knightly holdings of western Europe – thus resulting in a greater number of Themata troops albeit with relatively lower quality equipment and training. This starkly contrasts with the traditional infantry-heavy legions of the erstwhile Roman Empire of the 2nd-3rd century AD. At the same time, it should be noted that not all such provincial troops of the Byzantine army were uniformly ‘poor’.

In fact, as mentioned in Tactica, some members of the Thematic army comprised rich landowners who could afford better armor and weapons – and as such, they were considered the first line of defense by the Emperor himself.

Furthermore, in spite of the non-uniformity of equipment showcased by different provincial troops, there was a minimum threshold of requirement expected from each farmer-soldier who held land. For example, in the 9th century AD (Middle Byzantine Period), the Byzantine Empire passed a law that allowed poor Themata soldiers to band together to pay for a properly equipped mounted warrior.

In rare cases (as legislated by Emperor Nikephoros II), some of the richer troops of the Byzantine army were obligated to furnish better equipment for their poorer military brethren. And during extreme situations, if the soldier couldn’t afford his arms and armaments – even after being offered aid from others, his land was promptly taken away. Consequently, he was drafted into the irregular divisions that were derogatorily called the ‘cattle-lifters’.

So, in essence, as opposed to 10th-century feudal Europe’s wide gap between the early knightly class and the ‘rag-tag’ peasant infantry, the Byzantine army boasted a fairly consistent provincial military institution that was inclusive of different soldier types.

The entire Theme system, although denoting a primary military body, was further strengthened by an administrative network (although the scenario took a downturn by the second half of the 11th century). Furthermore, it should be noted that this administration of the Themata evolved over the centuries to encompass both civic and military jurisdiction.

Strength of the Provincial Army

The basic unit of each Thematic army in the Byzantine era possibly harked back to the aforementioned banda (each bandon ranging from 200 to 400 men). Although in terms of practicality, the provincial soldiers were occasionally organized into the bigger turmai. Suffice it to say, the strength of each provincial army varied, dictated by the population of the said province.

For example, the Anatolikon province could possibly furnish around 10,000 soldiers, while the Armeniakon province could account for 9,000 troops. The smaller provinces, like Thrace, could approximately provide 5,000 provincial soldiers. And the overall strength of the Byzantine Themata army possibly numbered between 70,000 to 90,000 men, in circa early 10th century AD. The number of this Byzantine field army drastically decreased to possibly 40,000 troops during the 12th century.

Now as historian Ian Heath noted that some of the themes were further divided or even expanded, based on the political and military scenario of the period – which, in turn, had an effect on the manpower of the province. Moreover, the Byzantine realm also had strategic frontier themes, known as kleisourai (or ‘mountain passes’) that were mostly created from the border districts.

These particular provinces tended to maintain a more autonomous army linked by forts and castles, and the battle-hardened soldiers were commanded by the border nobles known as the akritai. On occasions, even the younger sons of the ‘interior’ Thema landowners joined the ranks of border armies, thus militarily reinforcing many strategic locations of the Byzantine Empire.

Payment and Rations of Ordinary Byzantine Soldiers

As we fleetingly mentioned before in the article, the Byzantine army of the Theme system was relatively well paid, especially when compared to the European realms of the contemporary time period. In terms of actual figures, a regular Thema soldier was possibly paid one (or one-and-a-half) gold coin, known as the nomismata, per month.

Each nomismata weighed around 1/72th of a pound, which equates to 1/6 to 1/4th of a pound of gold for the individual soldier per year. This increased to 3 pounds of gold per year for ‘fifth-class’ strategos and 40 pounds of gold per year for ‘first-class’ strategos. It should also be noted that additionally, these farmer-soldiers held their grants of land, which theoretically were valued at over 4 pounds of gold.

Now of course, much like in the earlier Roman Empire, the payment system must have had its limitation. For example, Emperor Constantine VII (or Porphyrogenitus – ‘the Purple-born’), the son of Leo VI the Wise, talked about how the Byzantine army at the provincial level was paid once in four years in the ‘old times’.

This could have meant that the provincial troops served in a cyclic manner, thus alluding to the rota system that possibly came into force every three years, which in turn might have provided a fresh batch of permanent soldiers for each year.

However, on the other hand, Arabic sources mention how most of the Byzantine forces (circa 9th century AD) were only paid once in four or five years, thus suggesting how the comprehensive payment scale occasionally put a strain on the treasury of the Empire.

In any case, the payment was also complemented by a rationing system, with dedicated rations being provided to the Thema soldier during his active duty. And like in many contemporary military cultures, the provisions were often bolstered by spoils and plunders gathered during both quick raids and extensive campaigns.

And interestingly enough, once again in stark comparison to early medieval European armies, disabled soldiers were expected to be endowed with pensions, while the widows of those who were killed in action were given a considerable sum of 5 pounds of gold (at least during the peak of the Byzantine army in circa 9th century AD).

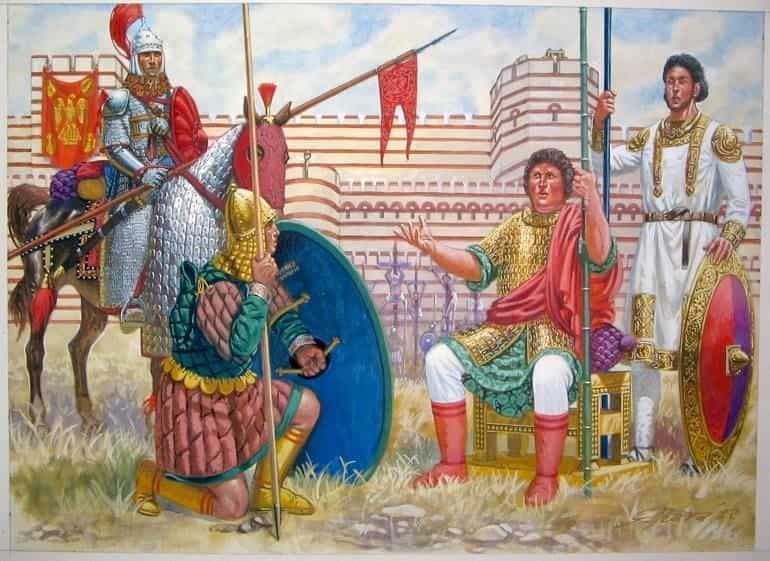

The Tagmata or the Elite Guard Regiments of the Byzantine Empire

Till now we have talked about the Themata army of the Byzantine Empire (circa 8th – 10th century AD). But the provincial troops were supported by the better-equipped and highly-trained Tagmata, the permanent guard regiments based in and around the capital of Constantinople. In essence, these elite units took the role of the nucleus of the early medieval Byzantine army and were possibly formed by Emperor Constantine V.

Pertaining to the latter part, the Tagmata were thus perceived as the Eastern Roman Emperor’s own formidable guards units who took the field only when their ruler set out on a campaign. But reverting to practical circumstances, during such military scenarios, some of the elite Tagma units must have also stayed back at Constantinople to guard the capital, while a few others were probably even committed to garrison duties in the proximate provinces like Macedonia and Thrace.

Scholai, Exkoubitoi, and Other Elite Regiments

The Scholai (Σχολαί, ‘the Schools’), probably the senior-most unit in the Tagmata, were the direct successors of the Imperial Guards established by none other than Constantine the Great. The other three principal regiments that were considered among the Tagmata ‘proper’ are as follows – the Exkoubitoi or Exkoubitores (‘Sentinels’), the Arithmos (‘Number’) or Vigla (‘Watch’), and the Hikanatoi (‘the Able Ones’) who were established by Emperor Nikephoros I in early 9th century AD.

There were also some other regiments that were occasionally counted in the imperial Tagmata roster, including the Noumeroi, who were possibly tasked with manning the walls of Constantinople, and the Optimatoi (‘the best’), who, in spite of their name, was relegated to a support unit that maintained the baggage train and garrisoned the nearby areas outside the capital.

Interestingly, there was also the Hetaereia Basilike (“the Emperor’s companions”), which was probably composed of foreign mercenary soldiers. During certain scenarios, men of the Imperial Fleet were also inducted into the Tagmata units.

Now when it comes to the number of soldiers of the Byzantine Tagmata, there is a lot of debate in the academic world. Early medieval sources rather mirror this state of confusion, with Procopius writing in the 5th century on how the Scholai was made up of 3,500 men. 10th-century Arab author Qudamah talked about how this number possibly rose to 4,000 per Tagma regiment in the 9th century.

However, yet another Arab author, Ibn Khordadbah mentioned how the total strength of the Tagmata army was 6,000 (which makes it 1,500 men per regiment), and they were supported by 6,000 servants. And finally, another historical source of the 10th century described how the Emperor in the campaign should be supported by at least 8,200 horsemen (all of these figures are mentioned in ‘Byzantine Armies 886–1118′ by Ian Heath).

Presuming these horsemen to be from the Tagmata, we can surmise that in normal scenarios, the Emperor possibly boasted over 12,000 elite troops – and the number possibly even crossed 25,000 in the latter decades of the 10th century.

The Renowned Military Units of the Byzantine Army

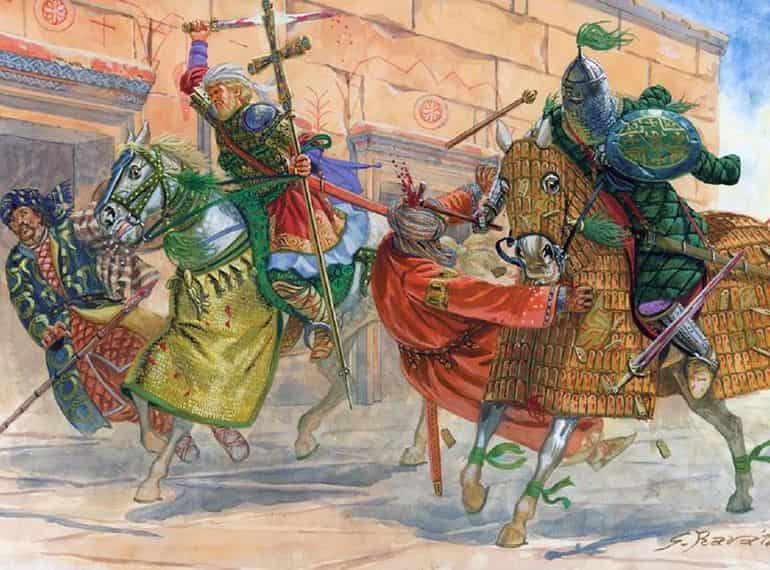

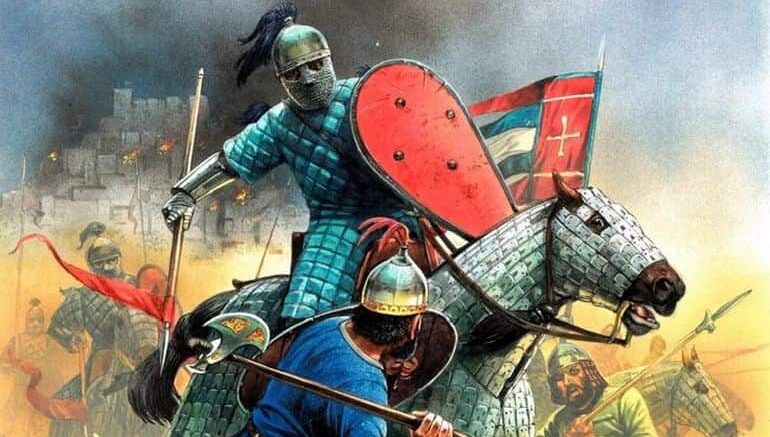

The Cataphracts

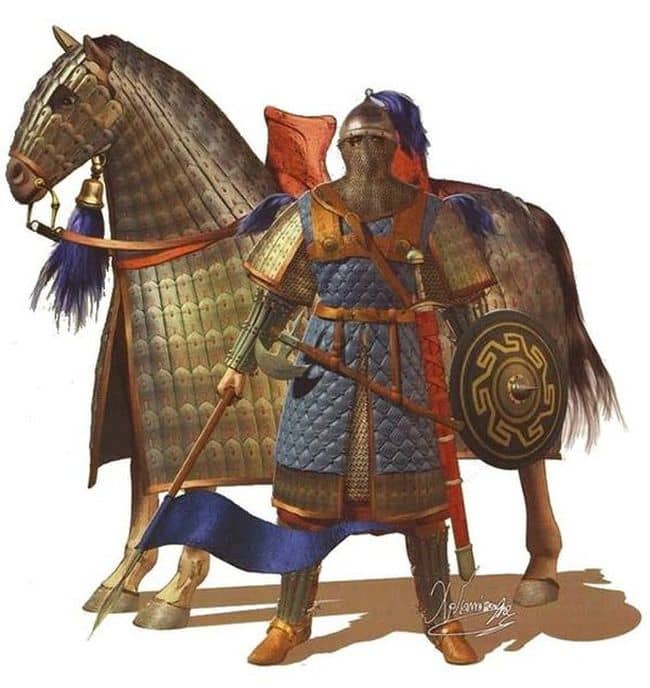

The very term ‘Cataphract’ (derived from Greek Kataphraktos – meaning ‘completely enclosed’ or ‘armored’) is historically used to denote a type of armored heavy cavalry that was originally used by ancient Iranian tribes, along with their nomadic and Eurasian brethren.

To that end, the Eastern Romans adopted the cataphract-based mounted warfare from their eastern neighbors – the Parthians (and later Sassanid Persians), with the first units of the heavy cavalry being inducted into the Roman Empire army as mercenaries (probably raised from mounted Sarmatian auxiliaries).

And interestingly enough, the subsequent Byzantine army maintained its elite heavy cavalry units of cataphracts from antiquity till the early middle ages, thus ironically carrying on the tradition of Eastern equestrianism.

In any case, the Eastern Roman Cataphract of the Byzantine army fielded till the 10th century, was known for its super-heavy armor and weapons (that included maces, bows, and rarely even javelins). Typical contemporary descriptions of the cavalrymen mention the use of klibanion, a type of Byzantine lamellar cuirass that was crafted of metal bits sewn on leather or cloth pieces.

This klibanion was often worn over a mail corselet, thus resulting in a heavy ‘composite’ armor, which was further reinforced by a padded armor worn under (or over) the corselet. This tremendously well-protected scope was complemented by other armor pieces, like vambraces, greaves, leather gauntlets, and even mail hoods that were attached to the helmet.

Now in terms of military history, the Kataphraktoi or their brethren Klibanophoroi (a super-heavy cavalry unit revived by Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas) certainly required costly equipment and armaments, which could have possibly limited these units only to the Tagmata – the professional standing army (or Imperial Army of Byzantine emperors).

It is also interesting to note that Emperor John I Tzimiskes raised another unit of heavily armored shock cavalry – known as the Athanatoi (or ‘Immortals’). According to contemporary sources, these cavalrymen were draped in exquisite armor, and described as “armed horsemen adorned with gold”.

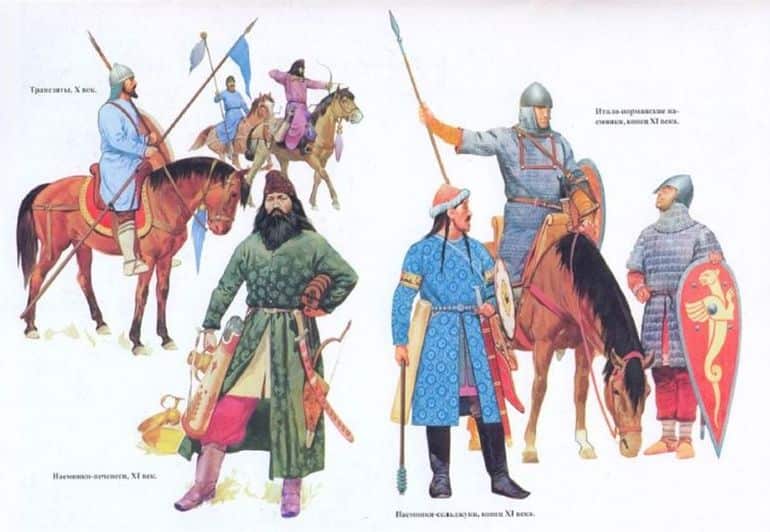

The Mercenaries – From Pechenegs, Normans, to Norsemen

By the end of the 10th century, the manpower derived from most Themes in Anatolia began to dwindle; while by the end of the 11th century, the quality of the new native Byzantine troops declined – so much so that their land-owning positions were gradually taken over by Armenians (and related Cappadocians), Varangians, Slavs, and even Franks.

Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas, who was also a brilliant military leader, perceived this ‘slackening’ trend and already took steps that would allow the employment (and even recruitment) of mercenaries in the Themata army.

In fact, according to credible estimates made by historians, by the end of the 10th century (and early 11th century), possibly more than half of the fighting men in the Byzantine army were mercenaries who came from different ethnic backgrounds.

Now if we proceed to a century later, Frankish sources talked about the various mercenary elements found in Emperor Alexios I Komnenos’ army, including the Patzinaks, Alans, Kipchaks, (Cumans), Bulgars – and these groups possibly formed the core of the missile cavalry (like cavalry archers). To that end, Nikephoros II’s light cavalry divisions were mostly composed of the Patzinaks (or Pechenegs), semi-nomadic Turkic people who originally hailed from Central Asia.

These light cavalrymen were complemented by their ‘heavier’ brethren, along with the infantrymen and marines – derived from the Anglo-Saxons, Rus (early Varangians), Franks, Italians, Dacians, and even Normans.

And quite intriguingly, this system of employing foreign mercenary troops even took an administrative route (possibly as an alternative to the depreciating Theme system) that streamlined the foreign troops into self-contained contingents known as the symmachoi (‘allies’) that were commanded by their own officers and leaders.

The Varangian Guard

Incredibly enough, the famed Varangians Guards were indeed employed as mercenaries as opposed to guard units like the Scholai and Exkoubitores. Now employing mercenaries was a trademark of Byzantine military stratagem even in the earlier centuries (as we discussed in the last entry). But the recruitment of the Varangians (by Emperor Basil II in 988 AD) was certainly different in scope, simply because of the loyalty factor.

In essence, the Varangians were specifically employed to be directly loyal to their paymaster – the Emperor. To that end, unlike most other mercenaries, they were dedicated, incredibly well trained, furnished with the best of armors, and most importantly devoted to their lords (the Byzantine Emperors). And unlike other imperial guard regiments, the Varangian Guard was (mostly) not subject to political and courtly intrigues; nor were they influenced by the provincial elites and the common citizens.

Furthermore, given their direct command under the Emperor, the ‘mercenary’ Varangians, as professional and loyal troops, actively took part in various encounters around the empire – thus making them an effective crack military unit, in contrast to just serving ceremonial offices of the royal guards.

In any case, the popular imagery of a Varangian guardsman generally reverts to a tall, heavily armored man bearing a huge ax resting on his shoulder. This imposing ax in question entailed the so-called Pelekys, a deadly two-handed weapon with a long shaft that was akin to the famed Danish ax. To that end, the Varangians were often referred to as the pelekyphoroi in medieval Greek.

Now interestingly enough, while the earlier Pelekys tended to have crescent-shaped heads, the shape varied in later designs, thus alluding to the more ‘personalized’ styles preferred by the guard members. As for its size, the sturdy battle-ax often reached an impressive length of 140 cm (55 inches) – with a heavy head of 18 cm (7-inch) length and a blade width of 17 cm (6.7-inch). And lastly, it should also be noted that the Varangians mostly played their crucial roles after the military peak of the Byzantine army (post-11th century) – an age that is not the focus of our article.

The Evolution of the Byzantine Army – Visual Presentation

YouTuber foojer has aptly furnished a flourishing visual scope to this millennium-long military tradition of the Eastern Roman Empire accompanied by short information snippets that mention the evolution of armor and soldier panoply for the Byzantine infantrymen. As the creator of the time-lapse video makes it clear –

I’ve chosen to call them Byzantines instead of Eastern Romans for the sake of convention, and I’ve chosen to focus on native heavy infantry, excluding mercenary and guard units (sorry, Varangian fans).

By order of appearance: three infantrymen from the Byzantine ‘Dark Ages’ (~7th to 9th centuries); five infantrymen from the Macedonian dynasty (10th to 11th centuries); two infantrymen from the Komnenid dynasty (11th to 12th centuries); three infantrymen from the Laskarid dynasty (13th century); four infantrymen from the Palaiologian dynasty (13th to 15th centuries); one warrior from the Trapezuntine Empire (which survived until 1461)

The armor and weapons are mostly stylized though I’ve tried to include as much detail as possible. One point to note: my portrayal of the 1453 household trooper as heavily orientalized is controversial, but given the direction Byzantine costume was headed (check out the medallion of Emperor John VIII, and note how Trapezuntine warriors in 1461 were almost indistinguishable from their Turkish opponents), I think it makes a lot of sense.

*The article was updated on October 1st, 2022.

Book References: Byzantine Armies 886–1118 (By Ian Heath) / Byzantium and Its Army, 284-1081 (By Warren Treadgold)

Online Sources: The Ancient World / Hellenica World / Byzantine Military (link here) / National Hellenic Research Foundation

Be the first to comment on "Byzantine Army: Organization, Units, and Evolution"