Historical facial reconstructions provide us with a glimpse into the past in a manner that we can visually connect to our ancient predecessors. However, it should be noted that most of these reconstructions, while guided by empirical evidence, are based on educated appraisements, thereby presenting approximations of the facial structure of the individual. Taking this into consideration, let us take a gander at six facial reconstructions of ancient Egyptians, from the period between circa 15th century BC to the 1st century BC.

Contents

- Nebiri, an Egyptian Dignitary (circa 15th century BC)

- Nefertiti, Egyptian Queen (circa 14th century BC)

- Tutankhamun, an Egyptian Pharaoh (circa 14th century BC)

- Ramesses II, an Egyptian Pharaoh (circa 13th century BC)

- Meritamun, an Egyptian Noblewoman (possibly before circa 1st century BC)

- Cleopatra, Female Ruler of the Ptolemaic Dynasty (circa Ist century BC)

Nebiri, an Egyptian Dignitary (circa 15th century BC)

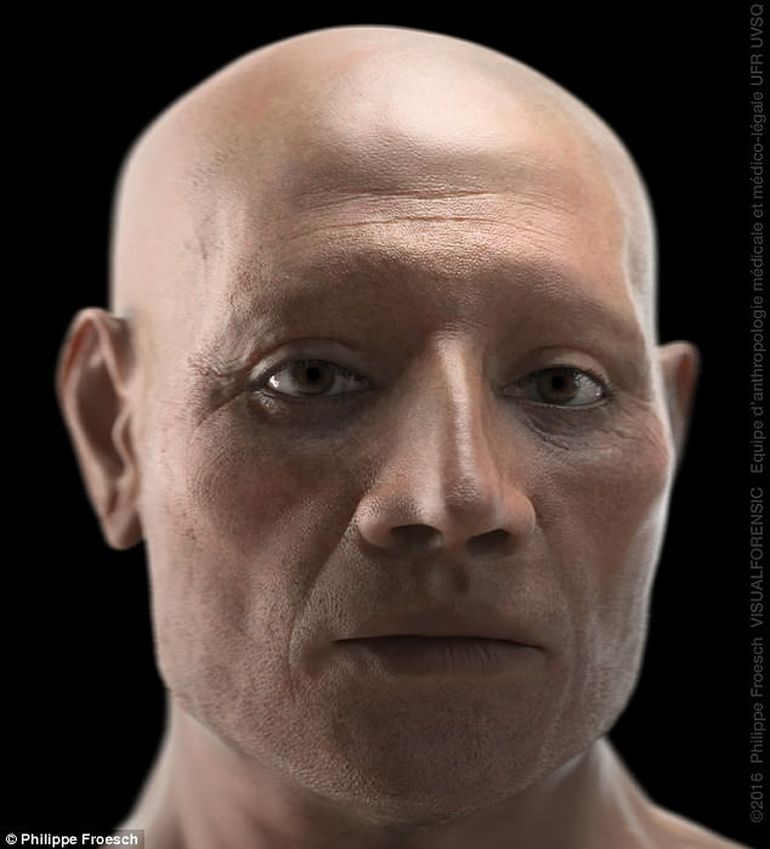

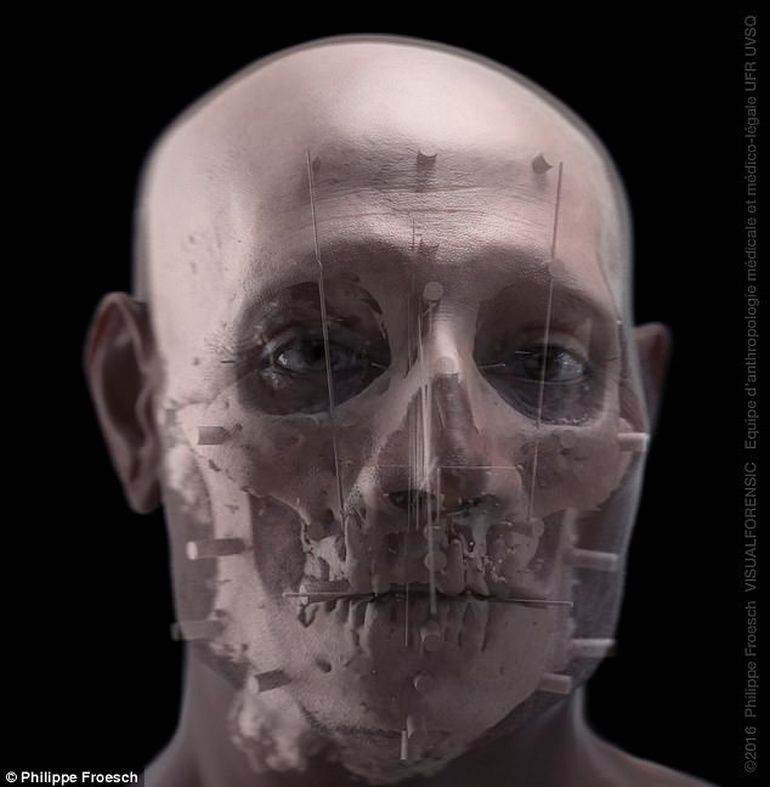

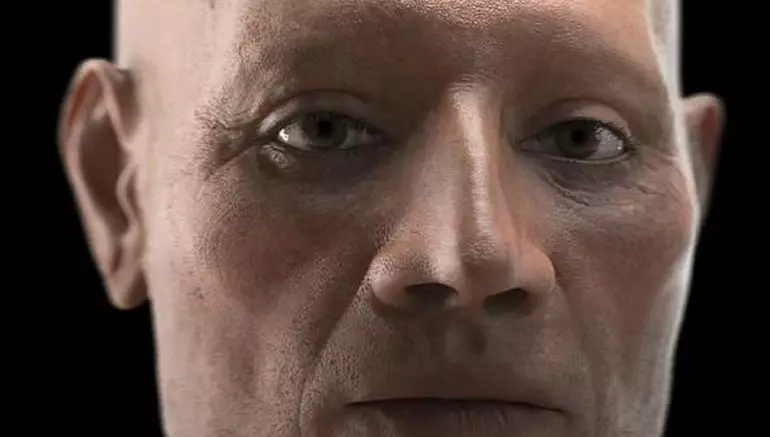

Nebiri was an ancient Egyptian dignitary who lived during the time of the 18th dynasty, corresponding to the reign of Pharaoh Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC). Now in terms of archaeology, Nebiri’s mummy showcased the oldest-ever case of chronic heart failure due to atherosclerosis (along with severe gum disease). But beyond modern reports, there is almost a sense of poetic justice when it comes to the history and reconstruction of Nebiri’s mummy.

To put things into context, Nebiri possibly died at the age of 45 to 60 and was buried in the Valley of the Queens (or Ta-Set-Neferu in Egyptian). However, his tomb was desecrated and looted in antiquity itself, while his body was intentionally damaged by the plunderers. The remnants of his mummy were re-discovered in 1904 and subsequently housed at the Egyptian Museum in Turin.

But in spite of such a regrettable fate of Nebiri’s mummy, it is modern forensic technology that has aided in ‘reviving’ the physical attributes of his face, thus once again bringing back the Ancient Egyptian dignitary to the historical limelight. To that end, this facial reconstruction was achieved by using computed tomography along with other techniques. And the result translates to the facial recreation of a man in his 50s with well-defined jawbones, a seemingly prominent nose, and slightly thick lips.

Interestingly enough, while Nebiri’s tomb was desecrated millennia ago, his head is often viewed as a good example of ‘perfect packing’ in ancient Egyptian times, according to a paper published in the journal Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology.

In fact, a CT scan has already revealed how the mummified head was preserved with the help of linen bandages that were carefully inserted in the nasal area, eyes, and mouth. An analysis made in 2013 showcased how these bandages were meticulously treated with a concoction comprising a balsam or aromatic plant, a coniferous resin, heated Pistacia resin, and finally animal fat (or plant-based oil).

Nefertiti, Egyptian Queen (circa 14th century BC)

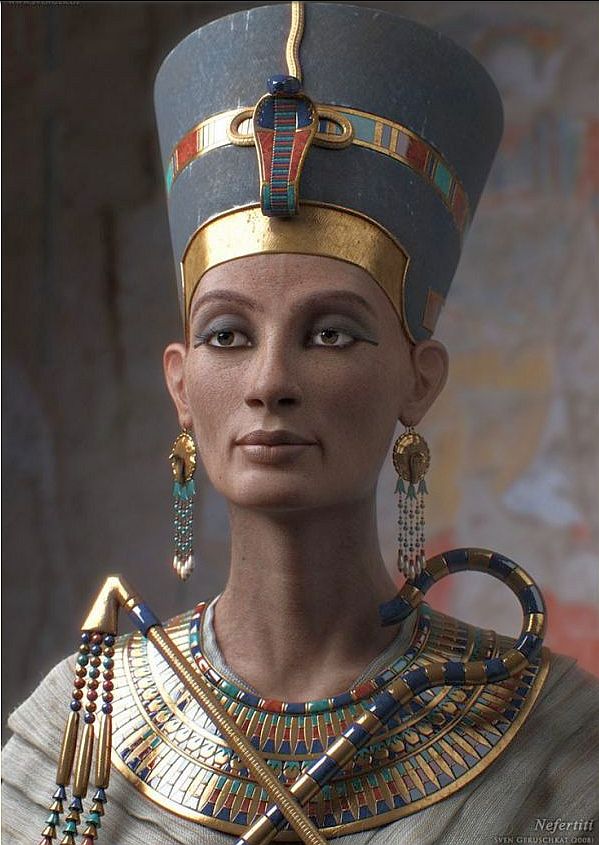

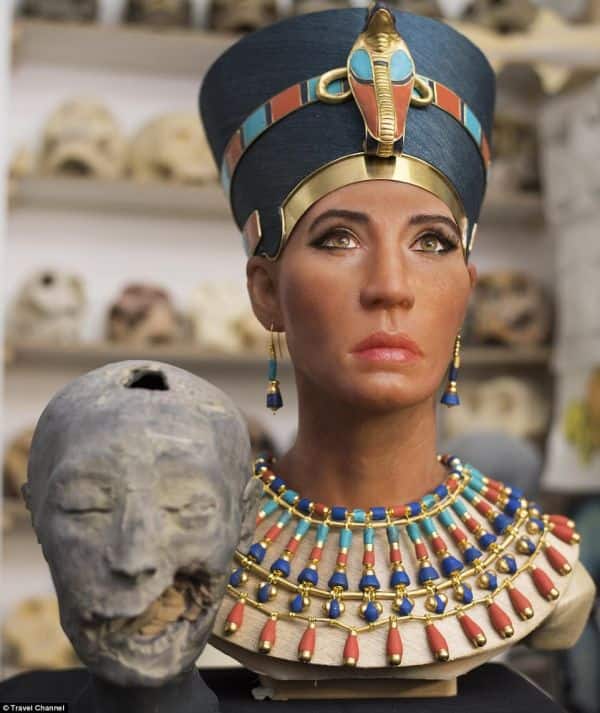

More than 1,300 years before the birth of Cleopatra, there was Neferneferuaten Nefertiti (‘the beauty has come’) – a powerful queen from ancient Egypt associated with beauty and royalty. However, as opposed to Cleopatra, Nefertiti’s life and history are still shrouded in relative ambiguity, in spite of her living during one of the opulent periods of ancient Egypt.

The reason for such a contradictory turn of affairs probably had to do with the intentional disassembling and expunging of the legacy of Nefertiti’s family (by successive Pharaohs) because of their controversial association with a religious cult that prescribed the relegation of the older Egyptian pantheon.

Fortunately for us history enthusiasts, in spite of such rigorous actions, some fragments of Nefertiti’s historical legacy survived through various extant portrayals, with the most famous one pertaining to her bust made by Thutmose circa 1345 BC.

The bust with its bevy of intricate facial features favorably depicts the ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertiti, possibly at the age of 25. In terms of the visual look, what we do know about Nefertiti, also comes from the royal portrayals on the numerous walls and temples built during the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep IV.

In fact, the depiction styles (and prevalence) of Nefertiti were almost unprecedented in Egyptian history till that point, with the portrayals quite often representing the queen in positions of power and authority. These ranged from depicting her as one of the central figures in the worship of Aten to even representing her as a warrior elite riding the chariot (as presented inside the tomb of Meryre) and smiting her enemies.

Talking about depictions, reconstruction specialist M.A. Ludwig has taken a shot at recreating the facial features of the famed Queen Nefertiti with the aid of Photoshop (presented above). Based on the renowned limestone Nefertiti Bust, Ludwig makes this point clear about the facial reconstruction –

I’ve seen artists try to bring out the living likeness of Queen Nefertiti many times, and some of the most famous attempts, though good in and of themselves, always seem to adjust her facial features to match certain contemporary standards of beauty in some way, which really isn’t necessary because the original bust of Nefertiti is already so beautiful and lifelike. I took the chance of leaving the bust’s features entirely as they are, only replacing the paint and plaster with flesh and bone. The result is absolutely stunning.

Interestingly enough, back in 2016, researchers from the University of Bristol also came up with their recreation of an ancient Egyptian queen, but the project was based on the mummy of The Younger Lady – the biological mother of Tutankhamun (and wife of Amenhotep IV), who was never proven to be Nefertiti herself.

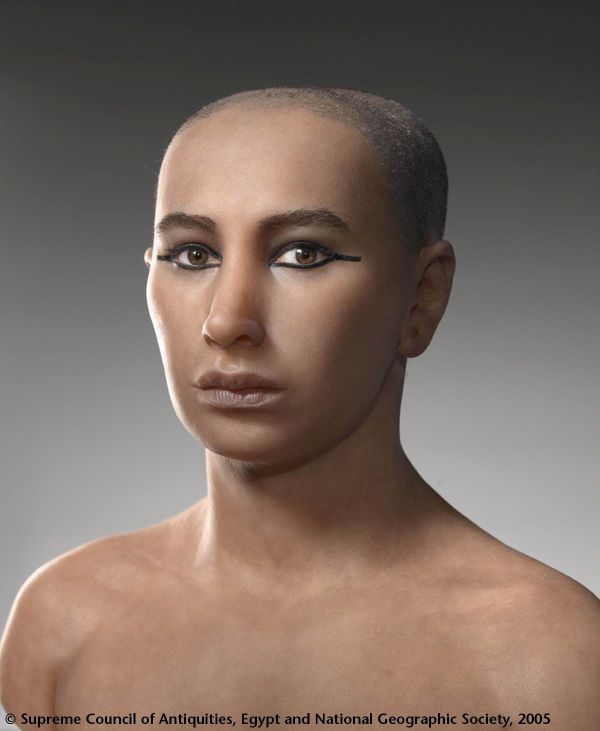

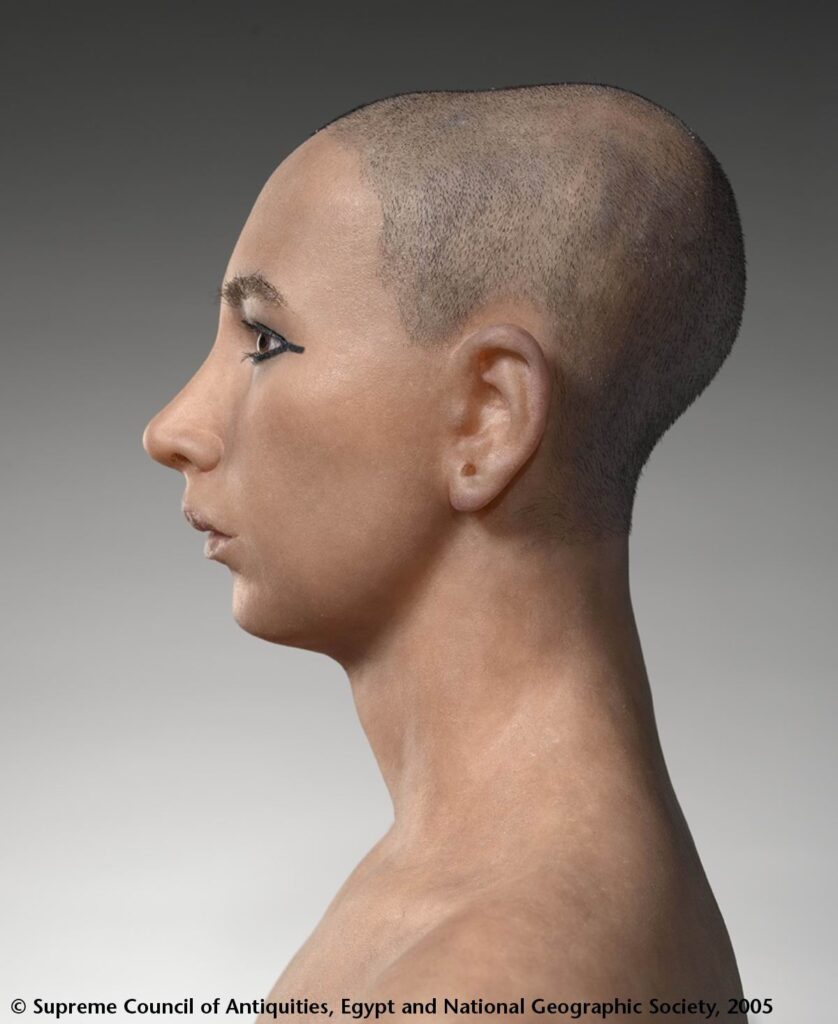

Tutankhamun, an Egyptian Pharaoh (circa 14th century BC)

Tutankhamun (‘the living image of Amun’), also known by his original name Tutankhaten (‘the living image of Aten’) was a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty – who only ruled for around a decade from circa 1332-1323 BC.

Yet his short reign was important in the grander scheme of things since this era not only coincided with Egypt’s rise as a world power but also corresponded to the return of the realm’s religious system to the more traditional scope (as opposed to the radical changes made by Tutankhamun’s father and predecessor Akhenaten – the husband of Nefertiti). The legacy of King Tut also has its fair share of mysteries, with a pertinent one relating to his still-unidentified mother, often only referred to as the Younger Lady.

Reverting to his own reconstruction, back in 2005, a group of forensic artists and physical anthropologists, headed by famed Egyptologist Zahi Hawass, created the first known reconstructed bust of the renowned boy king from ancient times. The 3D CT scans of the actual mummy of the young Pharaoh yielded a whopping 1,700 digital cross-sectional images, and these were then utilized for state-of-the-art forensic techniques usually reserved for high-profile violent crime cases. According to Hawass –

In my opinion, the shape of the face and skull are remarkably similar to a famous image of Tutankhamun as a child, where he is shown as the sun god at dawn rising from a lotus blossom.

Controversially enough, in 2014, King Tut once again went through what can be termed a virtual autopsy, with a bevy of CT scans, genetic analysis, and over 2,000 digital scans. The resulting reconstruction was not favorable to the physical attributes of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh, with emerging details like a prominent overbite, slightly malformed hips, and even a club foot.

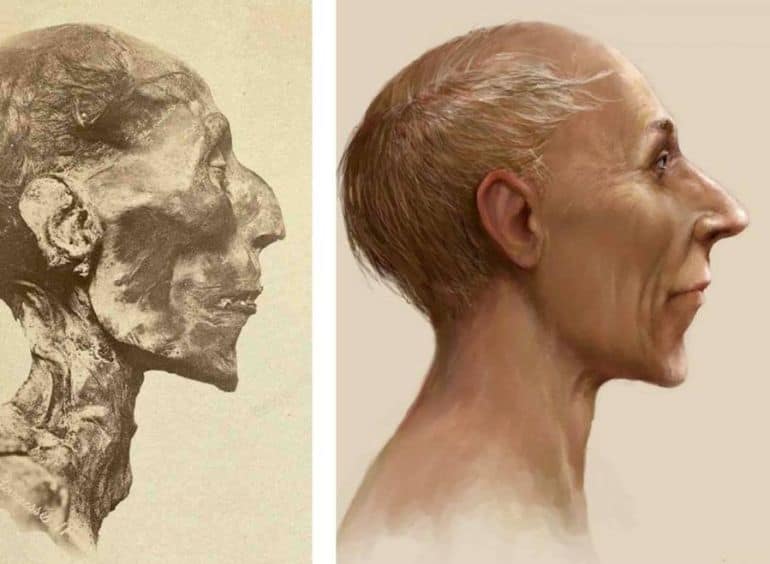

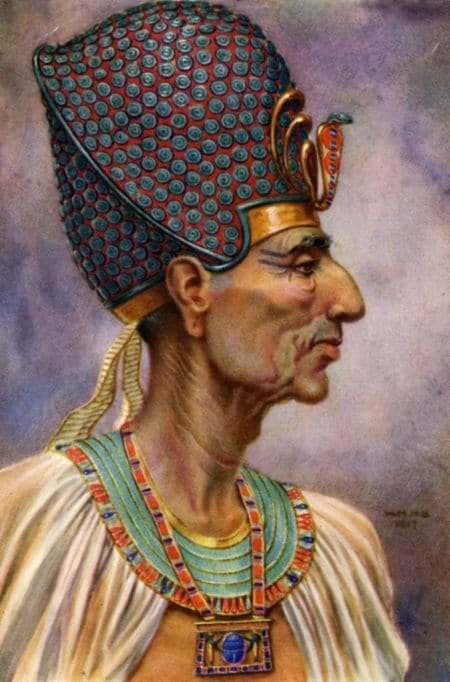

Ramesses II, an Egyptian Pharaoh (circa 13th century BC)

Ramesses II (also called Ramses, Ancient Egyptian: rꜥ-ms-sw or riʕmīsisu, meaning ‘Ra is the one who bore him’) is considered one of the most powerful and influential ancient Egyptian Pharaohs – known for both his military and domestic achievements during the New Kingdom era.

Born circa 1303 BC (or 1302 BC), as a royal member of the Nineteenth Dynasty, he ascended the throne in 1279 BC and reigned for 67 years. Ramesses II was also known as Ozymandias in Greek sources, with the first part of the moniker derived from Ramesses’ regnal name, Usermaatre Setepenre, meaning – ‘The Maat of Ra is powerful, Chosen of Ra’.

As for his reconstruction scope, after 67 years of long and undisputed reign, Ramesses II, who already outlived many of his wives and sons, breathed his last circa 1213 BC, probably at the age of 90. Forensic analysis suggests that by this time, the old Pharaoh suffered from arthritis, dental problems, and possibly even hardening of the arteries.

Interestingly enough, while his mummified remains were originally interred at the Valley of the Kings, they were later shifted to the mortuary complex at Deir el-Bahari (part of the Theban necropolis), so as to prevent the tomb from being looted by the ancient robbers.

Discovered back in 1881, the remains revealed some facial characteristics of Ramesses II, like his aquiline (hooked) nose, strong jaw, and sparse red hair. YouTube channel JudeMaris has reconstructed the face of Ramesses II in his prime, taking into account the aforementioned characteristics – and the video is presented above. A painting by Winifred Mabel Brunton also provides an estimation of the side profile of the Pharaoh at a slightly advanced age.

Meritamun, an Egyptian Noblewoman (possibly before circa 1st century BC)

Researchers (from multiple faculties) at the University of Melbourne have combined avenues like medical research, forensic science, CT scanning, and Egyptology, to recreate the visage of Meritamun (‘beloved of the god Amun’), an Ancient Egyptian woman who lived at least 2,000 years ago.

And the interesting part is – the scientists only had access to Meritamun’s mummified head, which on analysis alludes to how she met her demise at the young age of 18 to 25. But beyond her beautiful face, the researchers with their reconstruction project are looking forth to uncover more clues from the Egyptian’s ancient life, ranging from her actual time period, and diet to even the diseases she contracted during her lifetime.

The researchers were befuddled when they found out that they had full access to a mummified head in the university facility’s basement, possibly a legacy left behind by Professor Frederic Wood Jones (1879-1954), who undertook archaeological projects in Egypt. In any case, the team made a CT scan and found that the skull was in genuinely well-preserved condition, thus initiating the first steps toward a reconstruction process.

The researchers then went on to determine the gender of the mummy (head) by analyzing the bone structure of the specimen. Guided by the relative smallness of the jaw (and its angle), along with the narrowness of the roof of the mouth, the team found out that they were dealing with an Ancient Egyptian female; later confirmed by anthropologist Professor Caroline Wilkinson, who is famous for heading the reconstruction of King Richard III.

Interestingly, while the gender of Meritamun could be determined, the researchers are still working on the actual date of the mummy head itself. To that end, the specimen showcased significant levels of tooth decay, which could have been the effect of sugar, an item introduced to Egypt after its conquest by Alexander – thus placing Meritamun within the Greco-Roman time frame.

On the other hand, honey (known to Egyptians before Greek influence) could have also played a role in causing tooth decay. Furthermore, the high quality of the linen bandages wrapped around the mummy’s head hints at how Meritamun was probably a noblewoman, and she could have hailed from the time of native pharaohs – as long ago as circa 1500 BC.

Cleopatra, Female Ruler of the Ptolemaic Dynasty (circa Ist century BC)

Cleopatra – the very name brings forth reveries of beauty, sensuality, and extravagance, all set amidst the political furor of the ancient world. But does historicity really comply with these popular notions about the famous female Egyptian pharaoh, who had her roots in a Greek dynasty?

Well, the answer to that is more complex, especially considering the various parameters of history, including cultural inclinations, political propaganda, and downright misinterpretations. For example, some of our Hollywood-inspired popular notions tend to project Cleopatra as the quintessential Egyptian queen of ancient times.

However, in terms of history, it is a well-known fact that Cleopatra or Cleopatra VII Philopator (Romanized: Kleopátrā Philopátōr), born in 69 BC, was of (mostly) Greek ethnicity. To that end, being the daughter of Ptolemy XII, she was the last (active) ruler of the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty that held its major domains in Egypt.

In essence, as a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty, Cleopatra was a descendant of Ptolemy I Soter, a Macedonian Greek general, companion (hetairoi), and bodyguard of Alexander the Great, who took control of Egypt (after Alexander’s death), thereby founding the Ptolemaic Kingdom. On the other hand, the identity of Cleopatra’s grandmother and mother is still unknown to historians.

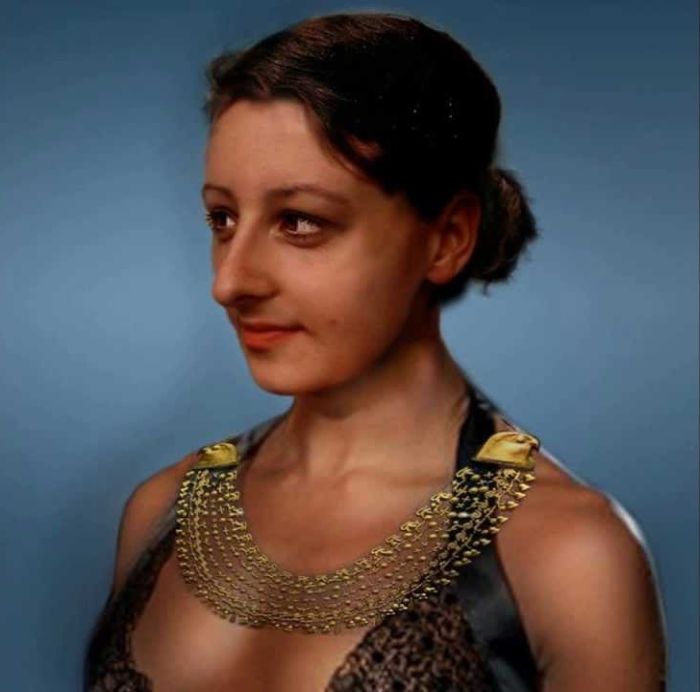

As for her reconstruction, one particular sculpture, thought to be of Cleopatra VII, is currently displayed at the Altes Museum in Berlin. Reconstruction specialist/artist M.A. Ludwig made her project based on that actual bust (except for the last video).

And please note that the following recreations are just ‘educated’ hypotheses at the end of the day (like most historical reconstructions), with no definite evidence that establishes their complete accuracy when it comes to actual historicity.

And while the animation will undoubtedly confuse many a reader and history enthusiast, actual written records of Cleopatra vary in their tone from a profusion of appreciation (like Cassius Dio’s account) to practical assessments (like Plutarch’s account).

Pertaining to the latter, Plutarch wrote a century before Dio and thus should be considered more credible with his documentation being closer to the actual time period of Cleopatra. This is what the ancient biographer had to say about the female pharaoh – “Her beauty was in itself not altogether incomparable, nor such as to strike those who saw her.”

Even beyond ancient accounts, there are extant pieces of evidence of Cleopatra’s portraiture to consider. To that end, around ten ancient coinage specimens showcase the female pharaoh in a rather modest light. Oscillating between what can be considered ‘average’ looking to representing downright masculine features with the hooked nose, Cleopatra’s renowned comeliness seems to be oddly missing from these portraits.

Now since we are talking about history, some of the masculine-looking depictions were possibly part of political machinations that intentionally equated Cleopatra’s power to her male Ptolemaic ancestors, thus legitimizing her rule.

Featured Image Source: TheLivingFace

Be the first to comment on "Facial Reconstruction of 6 Ancient Egyptians You Should Know About"