Introduction

From the other side of the silver screen, many of us gasped at the fictional atrocities committed at the unraveling event of the Red Wedding in the Game of Thrones (and in the Song of Ice and Fire). But as G.R.R Martin would be among the first to admit – many of his mind-concocted chapters are in fact inspired by real-life historical scenarios.

And while we are not exactly sure about the inspiration for the Red Wedding, in terms of ‘real’ history, it was the Abbasids who brought upon the aptly named ‘Banquet of Blood’. As can be gathered from the moniker, this episode pertained to an especially damning yet calculative ploy that wiped out around 80 family members of the preceding ruling house of the Umayyads at one go – after they were invited to a royal feast at abu-Futrus, near Jaffa on June 22, 750 AD.

Contents

The Start Of An Empire

The Umayyads took over the Islamic Caliphate by deposing the great and pious Caliph Ali in 657 AD, as a result of succession troubles that plagued the inheritors of Prophet Muhammed’s burgeoning realm. In fact, by doing so, their first Caliph Muawiya also inadvertently started out the very first Muslim dynasty.

Suffice it to say, the rise of the Umayyad dynasty paralleled other important developments in the Islamic world, namely the transfer of the caliphate’s capital from holy Medina to the strategic Damascus (in present-day Syria). This symbolic change in turn had much deeper consequences, with the ruling class once again relying on the long-urbane population of the Levant Arabs (many of whom were still Christians), as opposed to the loose tribal confederations of the ‘backwater’ of Arabia.

Now while the gargantuan Islamic empire under a single banner stretched from Iran to Spain, the practicality of the Umayyad power base had always been confined to Bilad al-Sham, a ‘metropolitan’ province (roughly corresponding to Syria) backed by the ahl al-Sham, the elite Syrian army largely composed of Arabs.

Consequently, Syria and Damascus became the center of attention and architecture for the ritzy Umayyad family members, who were already known for their extravagance and partiality to the Arabic ethnicity. Thus numerous mosques were constructed, and along with them sprang the contrasting decadent side of the ruling class, with ritzy ‘desert palaces’ and ‘retiring mansions’ being incessantly built for the elite members.

The Brewing Chaos

Unfortunately, for the Umayyads, their focus on both ethnocentrism and extravagance backfired in the long run. Concerning the first point, Islam by this time had started to spread beyond the borders of traditional Arabia and the Levant, with the religion especially catching up among adherents on the eastern side of the burgeoning realm – with regions like Iran and Transoxania being conquered by the superbly successful Muslim armies.

However, most of these newly converted Muslims (known as mawalis) – ranging from Persians, and Azeris to Turks, were considered second-class citizens within the empire, in spite of their advanced cultural legacy and norms. In essence, the Umayyads tended to favor the rights and (government) positions of the old Arab families based in the Levant, as opposed to the initially universalist concept of Islam.

Such measures gradually transformed the caliphate from a religious institution to an expansive dynastic territory ruled by a hereditary ruling class composed of ethnic (and favored) Arabs. The other part of the predicament was related to the Umayyad obsession with their kingship over the mulk or empire.

So, while their ritzy measures took the form of splendid buildings and opulent court lives within Syria, the Umayyads also had to face frequent conflicts and civil wars – including one that changed the entire branch of the ruling family from Sufyanid to the Marwanid. Such chaotic upheavals and inappropriate military endeavors started to chronically drain the Caliphate’s seemingly inexhaustible resources.

The Coming Of The Abbasids

Deriving their name from that of Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib, the uncle of the Prophet Muhammad, the Abbasids challenged the Umayyad rule by flaunting their lineage from the Hāshimite clan of the Quraysh tribe in Mecca.

Ironically, while their claim pertained to a closer bloodline to Muhammad and thus related to being ‘purer’ Arabs in nature, the Abbasid propaganda started in the distant oasis city of Marv in northern Khorasan (located near today’s Mary in Turkmenistan) – which was far away from the regions of Syria and Arabia.

In fact, the revolt was mainly supported by the Khurasani Arabs who had been living in distant Iran and Transoxania for almost a generation after the first Arab armies conquered the regions in the 7th century AD.

Suffice it to say, the Abbasids also appealed to the non-Arab Muslims (or mawalis), especially the culturally advanced Persians, who had generally been sidelined by the ruling Umayyads when it came to core government and military positions.

The opposition to the Umayyad rule culminated in a rebellion instigated by Ibrahim the Imam, who was fourth in descent from Abbas. And with the insurrections gaining momentum in the eastern parts of the Umayyad realm (along with Yemen), the scope quickly escalated into an open revolt under the leadership of the charismatic Abu Muslim, who was possible of Persian origin.

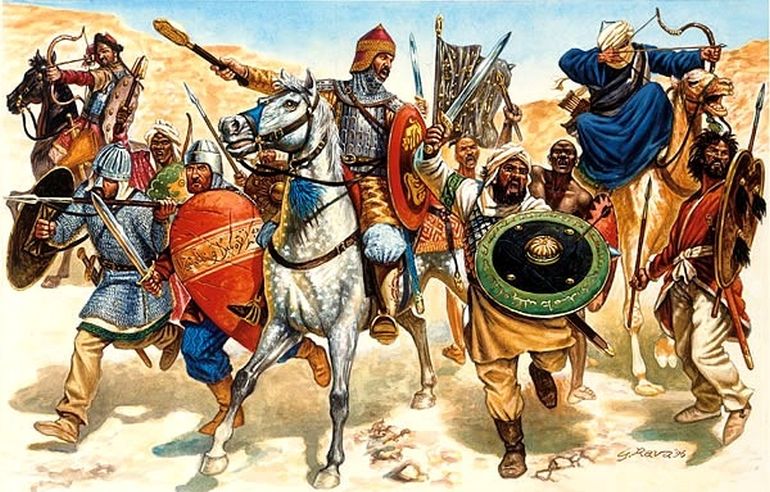

Thus tens of thousands of followers, with some experienced soldiers in their midst, thronged to the Black Standard of the Abbasids – and their armies swept across the Umayyad lands from the east. After a string of victorious engagements, the war was carried forth into the plains of Iraq. And the outnumbered Abbasids finally delivered a momentous defeat on the opposing Umayyad forces at the Battle of Zab (in January of 750 AD), thus effectively claiming the caliphate for themselves.

The Banquet Of Blood

It was Abu al-‘Abbas as-Saffah, a descendant of al-ʿAbbās, who was proclaimed as the first Abbasid Caliph. And in spite of their initially peaceful claims, the Abbasids were not above bloodshed tactics when it came to political maneuvers.

So after the rebels triumphantly stormed Damascus, as a result of their convincing victory at the decisive Battle of Zab, thousands were arrested and held in prisons on charges of subversion, while many of the Umayyad partisans were summarily executed in the coming months. The last Umayyad caliph Marwan II had already fled to Egypt, and he was also probably assassinated (or executed) shortly afterward.

However, by the middle of 750 AD, there were still remnants of the Umayyad ruling family members residing in their strongholds around the Levant. But as proven by the Abbasid track record, moral scruples took a back seat when it came to consolidating power – and thus the plan for the ‘Banquet of Blood’ was hatched.

Although not much is known about the exact machinations of this bloody event, it is generally believed that over 80 Umayyad family members were invited to a grand feast on the pretext of reconciliation. Given their desperate status and hope for fair surrendering terms, apparently, (almost) all of the invitees ceremoniously made their way to the Palestinian town of Abu-Futrus.

But once the feasting and festivities were done, most of the princes were remorselessly clubbed to death by the Abbasid followers – thus eliminating the possibility of Umayyad’s return to caliphate power.

Intriguingly enough, the Abbasids just about failed in their cold-blooded endeavor to completely wipe out the Umayyads, with a certain Rahman ibn Mu’awiya making his daring escapade all the way to distant Spain, where he declared himself as an independent Umayyad governor in 756 with his capital established at the majestic city of Cordoba.

But the “game of thrones” ended on a grisly note, with the largest land-based empire (up till then) being usurped almost overnight by a singular episode that involved both feasting and blood.

Sources: San.Beck / History of Islam / IranicaOnline / Quatr

Be the first to comment on "Banquet of Blood: Abbasids Wiped Out Their Opponents in a Feast"