Unlike some relatively well-documented mythologies in the world, ranging from Egyptian, and Indian, to Greek, Slavic mythology is mostly and rather unfortunately shrouded in obscure folklore. Some of these myths originated from pre-Christian Slavic realms and others from complicated Christian bias (that came centuries later).

However, there are some major deities whose names crop up from scant but near-contemporary sources, like the Primary Chronicle, a Kievan Rus annal that dates from circa 1113 AD. To that end, here we present a list of 12 enigmatic Slavic gods and goddesses. Few of the entries were drawn from hypotheses based on later medieval German sources.

Recognized Slavic Gods and Goddesses

Rod – Ancestor God

One of the primary examples of duality/polarity in Slavic mythology relates to the entity of Rod (and Rozanica – his female counterpart). Often perceived as the primordial god, Rod was possibly also venerated as the supreme god in various pre-Christian cultures of the Eastern and Southern Slavs.

In essence, his (scant) mythical narrative relates to how Rod is the creator (or progenitor) of the other Slavic gods and the universe, thus suggesting his early status as an important deity. To that end, the very name ‘Rod’ is derived from the Proto-Slavic word *rodъ, which relates to both ‘birth’, ‘family’, and ‘harvest’.

In view of this etymological connection, it can be surmised that Rod was probably venerated as the deity of families, agriculture, and rain; especially during the early Slavic period. However, he was replaced by Perun (described later in the article) – as can be discerned from his omission from the pantheon of deities worshiped by Vladimir the Great, circa the 10th century AD.

However, Rod was probably worshipped as Sud (‘The Judge’) by the southern Slavs. Interestingly enough, the female counterpart/s of Rod, collectively known as Rozhanitsy (or Sudzenitsy), were possibly venerated as multiple goddesses (much like the Fates of Greek mythology) who were perceived as protector deities of clans or tribes.

Perun – The God of Thunder

Probably the most well-known of Slavic gods and goddesses, Perun (or Grom) was venerated as the god of thunder, rain winter sun, justice (law), and war. In terms of mythology, he is symbolized by the oak – which exemplified the realms of the living and the sky.

To that end, etymologically the root perkwu in Proto-Slavic possibly meant oak, but later per meant strike – thus suggesting the evolution of Perun from a deity of just atmosphere to the all-encompassing deity of war and justice. This rather translates to his physical appearance – a strong bearded man armed with an ax (much like the Norse Thor).

Interestingly enough, the chief god in the mythical narrative, Perun, represents the steadfastness of oak of life, with his eagle-like form keeping a watch over the mortal realm from the highest branches of the tree. On the other hand, the root of the oak was symbolized by his nemesis Veles (discussed in the next entry), the dragon (or serpent) deity of water, and the dark underworld. This inevitably leads to clashes between these Slavic gods, especially after Veles tends to intrude upon the mortal realm – the domain under the protection of Perun.

As for the historical side of affairs, Perun, among all Slavic gods, has the most number of descriptions (although not all by name) in ancient Slavic texts. In fact, the deity is often co-identified with Perkunas, the Baltic god of thunder.

The Primary Chronicle (dating from circa 9th century AD) also mentions how Prince Oleg sealed a peace treaty with the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine) by invoking the weapons of Perun. Lastly, it is also mentioned how Vladimir the Great even installed an impressive statue of Perun, which was later discarded when Kievan Rus became Christianized under his rule.

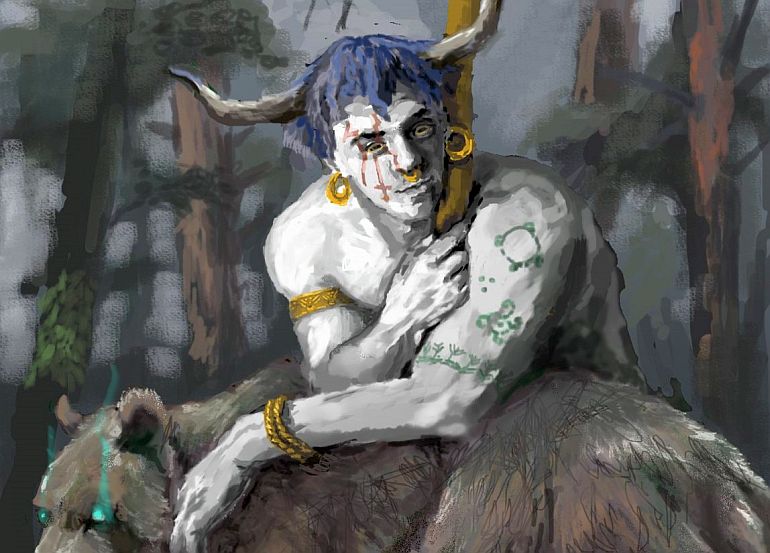

Veles – The God of the Underworld

The deity of many attributes, Veles (or Volos) is among the very few Slavic gods who find mention in most ancient and medieval Slavic domains. Talking of attributes, Veles was venerated as the god of livestock, earth, wealth, poetry, and even music.

However, there was a more disquieting side to the Slavic god, as can be discerned from his association with the underworld and water – which also made Veles the deity of departed souls, magic, and trickery. Pertaining to the latter-mentioned attributes, Veles was often projected as the nemesis (or antithesis) of Perun, the robust thunder god symbolizing the power of life.

Physically, Veles was often portrayed as a bearded man with dark, wooly features; while sometimes also depicted as a bald man with horns. In the mythical narrative of Slavic gods, Veles is also portrayed as the dragon or serpent who emerges from the fleece of darkened wool to strike at the base of the tree of life – the very guardianship of Perun.

In some myths, he goes on to abduct Mokosh – the consort of Perun and the goddess of summer, thus suggesting the eternal struggle between life and death and winter and summer. As for the historical side of affairs, Veles, by his name, was possibly mentioned for the first time in the Rus-Byzantine Treaty of 971 – wherein he is invoked as a deity who has the power to bring on diseases on oathbreakers.

Dazhbog – The God of Sun and Rain

Another one of the major Slavic gods, Dazhbog was venerated as the god of sun and rain in most pre-medieval Slavic cultures, often projected as being the son of Perun. From the etymological side, the word Dazhbog (or Dazhboh) is probably derived from Proto-Slavic *dadjьbogъ – which suggests that the solar deity also was possibly revered as a god (or giver) of wealth.

Interestingly, Proto-Slavic *bogъ (god) might even be related to Indo-Iranian Bhaga (meaning share or wealth), which suggests an older Indo-European origin of Dazhbog. The attribute of sharing wealth is also inducted into various Slavic myths of Dazhbog – some of which describe him as a wolf-pelt (or bear pelt) wearing man giving gold and fortune to people during the hard winter days.

In the historical context, the cult of Dazhbog was possibly demonized by later Christian practitioners, possibly (and quite ironically) because of its popularity in various southern Slavic states like Serbia. And talking of popularity, the sun deity was indeed beloved, possibly even as a cultural hero – as can be ascertained from Dazhbog’s mention in the Primary Chronicle.

In fact, just like his mythical father Perun, Dazhbog was said to have a splendid statue that was commissioned by Vladimir the Great (before his conversion to Christianity).

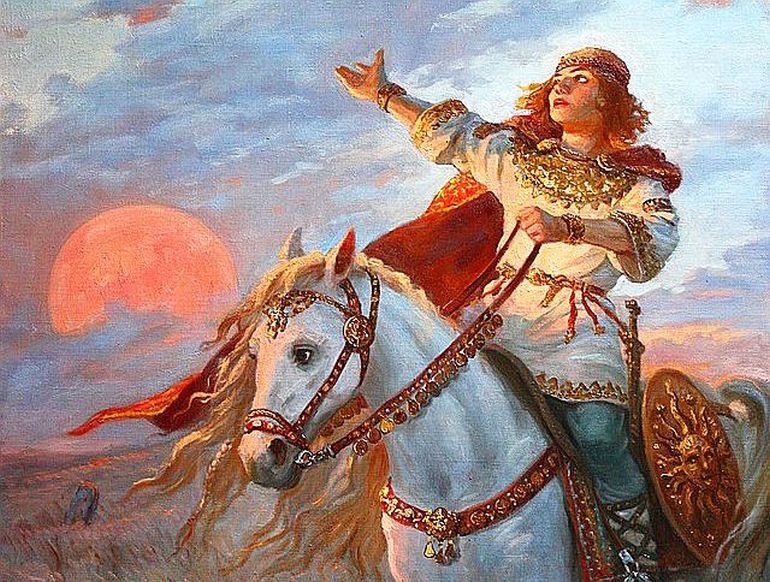

Yarilo – The God of Spring

Counted among one of the major Slavic gods, Yarilo (or Gerovit) was the deity of verdant vegetation, fertility, and the coming of spring. To that end, he has been often described as the typical birth-death cycle deity, however, with some fascinating Slavic traditions.

For example, Yarilo was venerated as the (lost) son of Perun, the supreme thunder god. But in spite of his lineage, he was rather adopted by Veles, the mighty god of the underworld – and there he was tasked with guarding the cattle of Veles. Interestingly enough, the Slavic version of the underworld was more akin to a utopian world of everlasting lush plants, green grass, and wetlands.

So in honor of Yarilo, during the springtime (when the deity symbolically made his way to the living world), many cities and villages, in the region of present-day Russia and Belarus, were often decorated with various motifs, like straw dolls. These were accompanied by chosen men dressed as the deity who headed processions throughout the countryside.

And so, spring was seen as a bountiful time of truce between the forces of life and death, wherein Yarilo falls in love with Morana – his twin sister, the goddess of nature and death. But after the harvest season was over, it was once again time for Yarilo to ritually ‘die’ or retreat into the underworld. This was mythically explained by his apparent unfaithfulness to his wife/sister, and his subsequent ‘murder’ or sacrifice – until his reemergence in the next spring cycle.

Considering the deity’s affinity with fertility, spring, and agriculture, Yarilo was unsurprisingly portrayed as a young man dressed in white, with a crown of flowers and armed with a wheat sheaf. However, in some striking historical folk accounts, Yarilo was also venerated with equine characteristics – sometimes as a young warrior riding atop a healthy horse and sometimes as an entity that could shapeshift.

Mokosh – The Goddess of Earth

Till now, we talked about the Slavic gods – however, among the major deities, Mokosh (or Mokoš) was considered the imperative (and even primordial) feminine deity of the Slavs in pre-Christian times. To that end, her origins possibly even date back to the Proto Indo-European age (circa 5th millennium BC), with the entity often likened to a mother goddess.

As for the Slavic scope, Mokosh, meaning ‘Friday’, was the goddess of earth, verdancy (and moistness of the land); and the protector of women, fishermen, and merchants. Her physical attributes are often described as a woman with long arms, thus suggesting her intricate connection to spinning and weaving – thus metaphorically also encompassing the destiny of women and their work.

In the mythical side of affairs, Mokosh was often portrayed as the (reluctant) wife of the supreme god Perun, possibly because of her affinity for the verdancy and moistness of the earth, as opposed to the ‘dryness’ of the sky god Perun. In some narratives, she is even said to have adulterous relationships with both Veles and Yarilo, with the latter spring ‘fling’ leading to the creation of the fruits of the earth.

Historically, Mokosh was held in high regard by the pre-Christian Slavs, so much so that construction was barred during spring – so as not to harm the pregnant earth. And like other primary Slavic gods, Mokosh was also said to have a statue erected by Vladimir the Great, before his conversion to Christianity.

Morana – The Goddess of Death

Morana (or Marzanna), unlike Mokosh, represented the ills and darkness of winter. To that end, Morana, was in many ways, the baleful representation of the advent of winter – the goddess signifying the cycle of death.

And historically (as in present days), winters were indeed harsh in most Slavic lands, with chilling temperatures accounting for the death and disease of both humans and livestock. Such events eventually tied Morana with misfortune, with mythical narratives of the crone goddess even dabbling in sorcery and creating nightmares.

Interestingly enough, in the etymological sense, Morana’s (or Marzanna) name is probably derived from the Proto-Indo-European root mar-, mor-, signifying death. In that regard, there are other ancient cultures (with Indo-European affinity) that had their own version of the crone goddess – like the Mariham of the Iranians.

And as for rituals, the rites of Marzanna (often called the feast of Maslenitsa) are even followed in our modern times, with a straw effigy of the goddess being dragged through the streets, burned in the fields, and then drowned during the coming of spring – thus signifying the end of winter.

Sventovit – The God of War

The Slavic god of war and abundance, Sventovit, literally the ‘strong lord’, was chiefly venerated by the West Slavic Rani tribe. His worship later spread to the Polabian Slavs – as is evident from the (oft-mentioned) sacred temple that was dedicated to him on the Baltic island of Rügen, north of present-day Germany.

According to medieval sources, the citadel temple was a grand example of pre-Christian Slavic architecture with the huge timber superstructure being topped by an immaculately placed red roof facade. Inside the monument, the enormous four-headed idol of Sventovit was placed – with the impressive figure holding a drinking horn made of various metals. Helmold’s Chronica Slavorum describes –

Every year, every man and woman paid a coin as a donation for the worship of this idol. The idol was also given a third of the loot and the results of plundering as if they had been attained and taken for his protection.

This same god had three hundred horses and the same number of men who served as warriors on them, and all of their earnings, obtained through arms or robbery, were given to the custody of the priest, who, using the profits from these things, would create different types of emblems and various adornments for the temple, and store them in tightly closed chests, in which, in addition to abundant money, a large amount of purple cloth had accumulated, eaten by time. There could also be seen an enormous amount of public and private donations, given by the fervent offerings of those who asked the deity for favors.

Now from the perspective of the mythical pantheon, there is a possibility that Sventovit was simply venerated as a conflation (or even substance) of the supreme god Perun. Animals and motifs such as white horses, eagles, and horns were usually associated with the deity.

Hypothetical Slavic Gods and Goddesses

Svarog – The God of Fire

In this section on hypothetical Slavic gods, we have decided to include a few Slavic gods whose origin myths are still debated in academic circles, with some hypotheses suggesting their possibly non-Slavic (or loaned background).

Svarog is one such deity whose historicity is questioned regarding his first mention – which was made in the Hypatian Codex, a 15th-century Russian compilation that, in turn, reverts to the translation of the 6th-century Byzantine cleric John Malalas. In the Russian text, the name of the Greek god Hephaistos is replaced with that of Svarog, thus making Svarog the god of fire and metallurgy.

Now, it is not entirely known if the Russian attempt to ‘match’ the deity was an intentional way to Slavonise the older Greek deity, or was it an honest (yet misguided) adaptation of older Slavic deities (who were related to fire).

From the etymological perspective, Svarog does seem to be related to Indo-European languages, like Svar meaning ‘gleaming’, while Svarg meaning ‘heaven’ in Sanskrit – thus potentially making Svarog the god of heaven or sky.

In other words, Svarog could have been venerated as a creator deity, whose eminence was probably reduced with the passage of time. But there is little evidence for Svarog being worshiped as a specific deity in pre-Christian Slavic lands.

Radegast – The God of Hospitality

A hypothetical West Slavic god of hospitality, Radegast (literally might translate to ‘dear guest’ or ‘welcomed guest) was also considered the deity of crops, war, and even the sun. Now historically, the name Radegast first comes up in the chronicle of Thietmar of Merseburg in the 11th century.

There it is mentioned that the god Svarogich (or Svarog) is the primary god in the city of Radegast – the holy site of the pagan Wendish tribe of Rethra. However, later German chroniclers reversed the name of the city with the god, thus suggesting the veneration of Radegast as a deity rather than a city.

Considering these conflicting accounts, the present-day hypothesis usually alludes to how Radegast might have simply been an opus borne by the misunderstanding of the early medieval German chroniclers. In that regard, Radegast might have been a conflation of the god Svarog.

In any case, Radegast has often been described as a man dressed entirely in black with a swan-ornamented helmet, shield, and spear – who is invited as a guest of honor to banquets and feasts. There is also an ominous side to the deity, with one particular 12th German chronicle mentioning how human sacrifices were offered to Radegast.

Belobog/Chernobog – The Dual Gods of Light and Darkness

According to a few credible studies, Chernobog (the Black God) and his antithetical counterpart Belobog (the White God) might just be inventions (or possibly alterations) made by later Christians. Now if viewed from the prism of popular culture, both of these Slavic ‘gods’ are made quite famous through the fictional works of modern writers, like American Gods by Neil Gaiman.

However, historically, the very first mention of Chernobog is made in Chronica Sclavorum (or Chronicle of the Slavs), a medieval document compiled by Helmold of Bosau, a Saxon priest in the late 12th century – a time period that is two hundred years after the Christianization of most Slavic lands.

Interestingly, while Chernobog was represented as a devil-like figure in the chronicle, Belobog was not even mentioned by Helmold – thereby suggesting that the latter deity was an assumed (and subsequently conceived) nemesis to the dark god.

Talking of history, Belobog was first mentioned in a 16th-century document known as the Chronicle of Pomerania. To that end, some historians consider the Belobog-Chernobog deities as notions or even nicknames for the duality of other gods.

In fact, this scope of duality between assumed light and darkness (if not necessarily good and evil) also plays out in the myths of important Slavic gods like Perun and Veles. In essence, while Belobog and Chernobog might not have been specifically venerated by the pre-Christian Slavs, folkloric versions of such deities may have existed in some Slavic realms.

Lada – The Goddess of Beauty and Love

And finally, much like the last two entries, the veneration of Lada in pre-Christian times is also debated by some modern-day academics. Usually considered the beautiful, voluptuous goddess of love and spring, Lada was perceived as the Slavic counterpart to Greek Aphrodite or even Norse Freyja. The latter connection becomes more evident when she is paired with her twin brother Lado (much like Freyr is with Freyja).

However, historically, the first mention of Lada possibly comes from the early 15th century – a period when most Slavic realms were already Christianized for centuries. To that end, Lada might even be an invention of anti-pagan Christian clerics in a bid to denigrate the ‘lustful’ nature of pagan religions.

Etymologically, Lada (or rather ‘Lad’) applies to ‘beautiful’ and even ‘order’ in various Slavic languages. To that end, Lada is represented as a crowned woman with pristine golden hair who looks over the domains of love, couplehood, marriage, and harvest.

And lastly, historically, while no records of Lada exist from pre-Christian times, the goddess indeed has various mentions in literary and religious works after the 15th century. One such example pertains to the Slavenskie skazki (“Tales of Desire and Discontent”), one of the works of 18th-century Russian novelist Michail Čulkov.

Online Sources and Citations –

https://www.thoughtco.com/slavic-gods-4768505

https://culture.pl/en/article/what-is-known-about-slavic-mythology

https://ia802604.us.archive.org/7/items/helmoldipresbyt00pertgoog/helmoldipresbyt00pertgoog.pdf

Be the first to comment on "The Most Enigmatic Slavic Gods and Goddesses"