Introduction – Difference between Galleys and Frigates

When it comes to history, maritime pursuits had undoubtedly enhanced the ‘reach’ of humankind, from the perspective of both migrational activities (like the Austronesian people) and trade networks (like the Phoenicians).

Over time, the coastal geographical locations of various settlements rather translated into strategic economic centers that were worth defending – thus giving way to the first naval powers of the world. This, in turn, led to the design and evolution of naval ships, namely warships, that were built for the dedicated purposes of defense and attack maneuvers.

Interestingly, the galley is one of the consistent design templates for such warships. It is basically a ship that is primarily propelled by rows (of oars) instead of sails. Consequently, the war galley survived in its various forms (with various weapon systems) for millennia, possibly from circa 1500 BC to 17th century AD, until the advent of more advanced naval crafts.

In essence, we must understand that a war galley is not exactly a definitive type of warship, but rather a general design upon which different types of warships are based on.

On the other hand, a frigate originally referred to any kind of warship with sails, built for speed and maneuverability, and as such tended to have a smaller size than the main warship. By the 17th century, frigates, known for their speediness, carried lighter armaments than the ‘ship of the line’.

The corvettes were even smaller than the frigates, sometimes modified from the sloops – and thus were only reserved for coastal defense (and raids) and minor engagements during the Age of Sails (1571–1862).

To that end, in this article, we will discuss the remarkable historical warships (some based on the galley design, while others based on sails) that have sailed the high seas, with the time period covering almost 2,500 years – from the 7th century BC till the 17th century AD.

Contents

- Introduction – Difference between Galleys and Frigates

- Bireme and Trireme (origins from circa 7th century BC)

- Liburnian (origins from circa 2nd century BC)

- Dromon (origins circa 4th-5th century AD)

- Fireship (used in different eras, from circa 5th century BC- 19th century AD)

- Viking Longship (circa 10th century AD)

- Carrack (origins in 14th century AD)

- Caravel (origins in the 15th century AD)

- Galleass (origins in late 15th century AD)

- Chebec (origins in 16th century AD)

- Turtle Ship (origins in the late 16th century)

- Galleon (origins in 16th century AD)

- Schooner (origins in the 17th century)

- Conclusion – Ship of the Line

Bireme and Trireme (origins from circa 7th century BC)

Herodotus mentioned penteconter, a type of ship that had a single set of oars (possibly numbering 25) on each side. This ship, with its function of bridging the gap between exploring and raiding, was probably one of the first types to be used by the Greek maritime city-states and colonies for communication and coastal control.

However, arguably the first known ship dedicated to naval warfare possibly pertains to the bireme. Boasting a much bigger design than the penteconter, a typical bireme of 80 ft in length (remus meaning ‘oar’ in Latin) had two decks of oars on each side, complemented by a single mast with a broad, rectangular sail. More importantly, befitting its status as a warship (or war galley), the bireme was also fitted with the embolon, the battering ram or beak that could smash into enemy vessels.

Now according to one hypothesis, the Greek bireme was possibly inspired by the fast-moving galleys used by the Phoenicians. However, within a matter of centuries, the bireme evolved into the trireme (with three decks of rows) with larger dimensions, sturdier design, double masts (one large and one small), and more crew members (possibly reaching 200, with 170 of them being rowers).

Furthermore, the command structure involving such trireme warships, especially in the ancient Athenian navy, was quite streamlined with a dedicated captain, known as the trierarch (triērarchos) who commanded his group of experienced sailors and oarsmen.

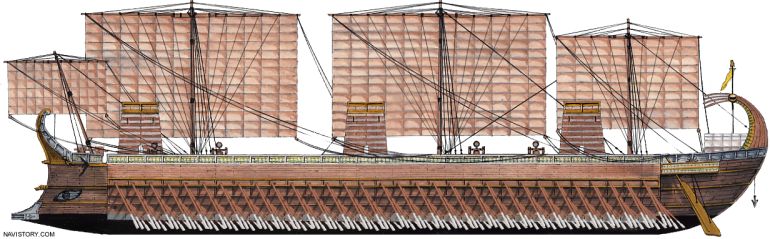

With the sheer domination of such war galleys in the ancient Mediterranean theater (circa 4th century BC), it should come as no surprise that the trireme further evolved into the quadrireme, the quinquereme, and so on. One pertinent example would relate to Tessarakonteres (diagram above) – belonging to Ptolemy (Ptolemaios) IV Philopator, who ruled the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 221 to 204 BC.

According to a description penned by Athenaeus, the giant Hellenistic warship with its 40 tiers of rows and seven rams was supposedly manned by 400 sailors (for rigging and regulating the sails); 4,000 rowers (for handling the oars); and 2,850 armed marines – thus accounting for a total of 7,250 men, which is more than the crew numbers required aboard the largest existing aircraft carrier in the world!

The Roman Republic and the Carthaginian Empire were also known for maintaining a large fleet of quadriremes and quinqueremes, and as such, many of these warships were also fitted with artillery in the form of catapults and ballistae. Moreover, the Roman marines devised a mechanism known as corvus (meaning “crow” or “raven” in Latin) or harpago.

This was a sort of boarding bridge that could be raised from a 12-ft high sturdy wooden pillar and then rotated in any required direction. The tip of this bridge had a heavy spike (the ‘corvus‘ itself) that clung onto the deck of the enemy ship, thus locking the two ships together.

The Roman soldiers crossed across this makeshift bridge and directly boarded the enemy ship. This naval tactic gave the Romans the upper hand since they were known for their expertise in close-quarter combat.

Liburnian (origins from circa 2nd century BC)

After the Roman Republic gained its ascendance over the Carthaginians, its naval power was relatively secure, and as such, the status quo was reflected by the conventional fully-decked galleys equipped with partially-submerged rams, mechanical artillery, and possibly even turrets (for archers).

In a few cases, Roman ingenuity still won the day – with one example pertaining to the desperate Roman fleet, under the command of one Decimus Brutus, fighting the Veneti and their sturdy ships (during Caesar’s Gallic Wars, circa 56 BC). In response, Brutus devised the incredible tactic of using grappling hooks that would allow them to cut the rigging of the heavy Venetic vessels.

However, with the gradual supremacy of the Romans in the Mediterranean region, the state didn’t really require large ships for expansive military actions. Furthermore, a new kind of foe came to the fore by 1st century BC – the pirates with their lighter vessels who made frequent raids on the coasts of Illyria and the various islands of the Adriatic.

In response, the Romans adopted the designs of these lighter, more-maneuverable ships – and the result was the liburnian (liburnidas), a single-banked galley that was later upgraded with a second bank of oars. The name was possibly derived from the ‘Liburni’, a seafaring tribe from the Adriatic coast.

The Liburnian functioned as the faster warship-variant of standard biremes; and thus was used for reconnaissance, raids, and general escort duties for merchant vessels. Over time, there were various types of Liburnian warships, with some fitted with heavier frames and rams for better offensive capability (rather than speed).

In fact, by the time of the emergence of the Roman Empire, the Liburnian was basically used as a blanket term for most types of Roman warships (and even cargo vessels). As for the historical significance, Agrippa was known to have effectively used his fleet of liburnian warships against the forces of Marc Antony and Cleopatra, in the decisive Battle of Actium, in 31 BC.

Dromon (origins circa 4th-5th century AD)

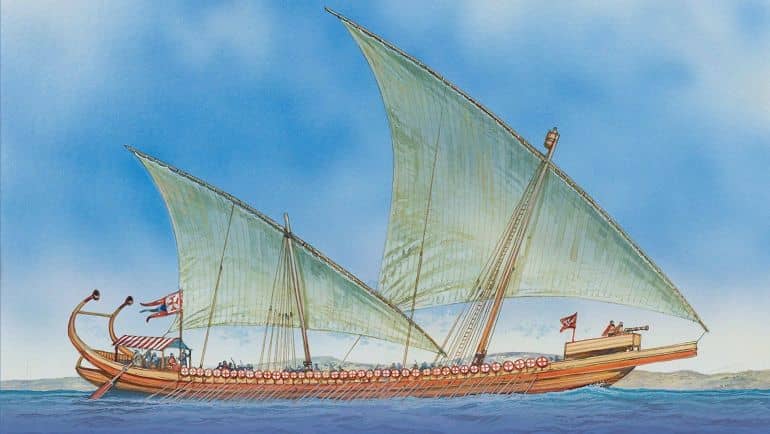

The most prevalent warship by circa 5th century AD (till 12th century AD), especially in the Mediterranean waters, pertained to the dromon (‘runner’ or ‘racer’). As could be ascertained from the name itself, this galley-type vessel was designed as a fast craft that eschewed the outrigger used in earlier Greek and Roman warships.

According to some historians, the dromon might have been the evolution of the liburnian, and as such was the mainstay of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) navy that maintained its naval supremacy during the early medieval era. Dromon-type galleys (or at least similar warships) were also used by their proximate foes, namely the Arabs, circa 7th century AD.

In terms of modifications in design, the dromon possibly boasted a full deck (katastrōma) that may have carried artillery, while also conspicuously having no battering ram. Instead, the warship was fitted with an above-water spur (with a sharp point) that was used for breaking enemy oars, as opposed to puncturing hulls.

One can also hypothesize how the dromons, irrespective of their single bank or two banks of oars, were fitted with the effective lateen sails (triangular shaped), possibly introduced by the Arabs, who, in turn, derived the technology from the Indians.

Fireship (used in different eras, from circa 5th century BC- 19th century AD)

In terms of naval technology, fireship is a blanket term used for different types of warships that were used with various tactical outcomes. For example, one of the oldest accounts of a ‘fire ship’ pertains to a ship literally set on fire by the Syracusans, who then guided the burning vessel towards the Athenians (during the Sicilian expedition, circa 413 BC).

The latter, however, was successful in mitigating the danger by putting out the flames. A similar type of tactical ploy was also used during the Battle of Red Cliffs (circa 208 AD) when General Huang Gai let loose fire ships (stocked with kindling, dry reeds, and fatty oil) towards his enemy Cao Cao.

On the other hand, an arguably more effective version of the fireship was devised by the Eastern Romans (Byzantine Empire) during their momentous encounter against the Arabs, circa 677 AD. Utilizing the aforementioned dromon-type warships, the Romans fitted their darting galleys with special siphons and pumping devices, instead of the usual beak (or spur).

These siphons spouted ‘liquid fire’ (or Greek Fire) that continued to burn even while floating in the water. In fact, some writers have gone on to explain how the viciously efficient Greek Fire could only be mitigated by extinguishing it with sand, strong vinegar, or old urine.

Suffice it to say, the weapon and the fireship were perfectly tailored to naval warfare; and as such the Eastern Roman Empire used it in numerous marine-based encounters to secure victories – with notable examples involving the crucial successes achieved against two Arab sieges of Constantinople.

However, the procedures of making and (subsequent) deployment of Greek Fire remained a closely guarded military secret – so much so that the original ingredient has actually been lost over time. Still, researchers speculate that the composition of the substance might have pertained to chemicals like liquid petroleum, naphtha, pitch (obtained from coal tar), sulfur, resin, quicklime, and bitumen – all combined with some kind of a ‘secret’ ingredient.

Furthermore, there are 11th-century conceptions pertaining to Northern Song Dynasty fireships that were possibly equipped with flamethrowers that were similar to the Greek Fire mechanisms of the Eastern Roman Navy. By the Age of Sails (1571–1862 AD), various navies used explosive fireships.

These vessels, drizzled in tar and fat and filled with gunpowder, were operated by a small crew who made their escape during the last moments before the incendiary fireship could run into an enemy craft. Suffice it to say, such ruthless naval tactics were usually reserved for assaults on anchored ships, rather than in the open seas.

Viking Longship (circa 10th century AD)

While Viking raiding ships were one of the defining features of Viking raids and military endeavors, these vessels had a variance in their designs – which is contrary to our popular notions. According to historians, this scope of variance can be credibly hypothesized from the sheer number of technical terms used in contemporary sources to describe them.

To that end, the Vikings before the 10th century made very few distinctions between their varied merchant ships and warships – with both (and other) types being used for overseas military endeavors. Simply put, the first Viking raids along the English coasts (including the plundering of the Lindisfarne monastery in 793 AD, which marks the beginning of the Viking Age) were probably made with the aid of such ‘hybrid’ ships that were not specifically tailored to military purposes – as opposed to the ‘special’ ships showcased in The Vikings TV series.

However, in the post-9th-10th century period, the Viking raiders boosting their organized numbers by military establishments or ledungen, did strive to specifically design military warships, with their structural modifications tailored to both power and speed.

Known as snekkja (or thin-like), skeid (meaning – ‘that cuts through water’), and drekar (or drakkar, meaning dragon – derived from the famed dragon-head on the prow); these streamlined longships tended to be longer and slimmer while accounting for a greater number of oars. On the other hand, increased trading also demanded specialized merchant ships or kaupskip that were broader with high freeboards, and depended on their greater sail-power.

Given their svelte design credentials, the Viking longship traditionally required only a single man per oar when cruising through the neutral waters. But when the battle was at hand, the oarsman was joined by two other soldiers whose job was to not only give a lending hand (for increasing the ship’s speed) but also to protect the oarsman from enemy missiles. And as the Viking raids became more profitable and organized, the wealth was translated to even bigger and better warships.

One good example would pertain to the ship of King Olaf Tryggvason (who ruled Norway from 995 to 1000 AD) – aptly named Long Serpent. According to legends, this ship supposedly carried eight men per half-room (or oar) at the naval Battle of Svolder, which would equate to over 550 men overboard if we also count the other combatants.

Now in practical terms, this scenario might have been a bit exaggerated with probable translation issues. But even if we account for 8 men per room (or 4 men per oar), the total number of men that Long Serpent could carry would have gone beyond 300!

Carrack (origins in 14th century AD)

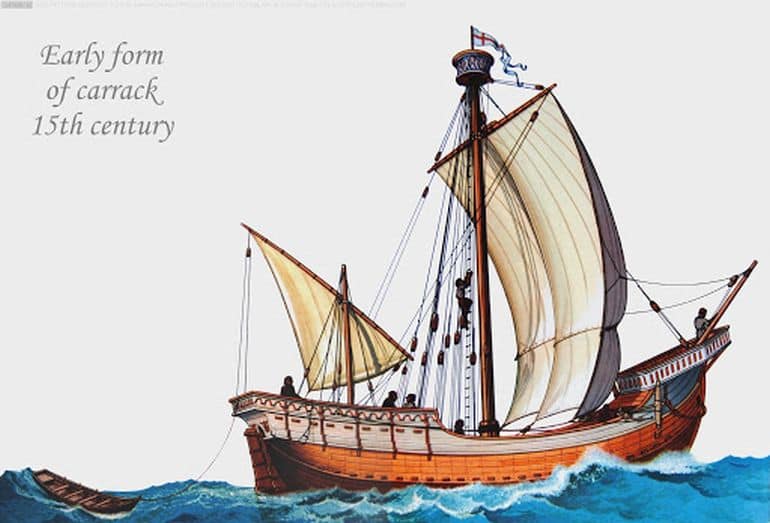

Considered one of the most influential ship designs in the history of navigation, the carrack was probably among the first sea vessels that evolved beyond the design of war galleys. In essence, the carrack eschewed any form of oar-based system, instead entirely relying on sails.

To that end, a fully-evolved carrack design was typically square-rigged on the foremast and mainmast and lateen-rigged on the mizzenmast. The size of the carrack, with its carvel-built robust hulls, also made it stand out from its galley-based predecessors, with some versions boasting capacities of around a whopping 1000 tons.

By the early 16th century, the carrack (also known as nao in the Mediterranean theater) became the standard vessel for the Atlantic trade routes and exploration. Simply put, the massive capacities of the carracks made them ideal candidates as merchant ships; while their sturdy design and high stern (with large highcastle, aftcastle, and bowsprit) made them effective as military warships.

Caravel (origins in the 15th century AD)

In reaction to the relatively ponderous nature of the aforementioned carrack-type warships and merchant vessels, the Portuguese (and later the Spanish) developed the caravel – a smaller but highly-maneuverable sailing ship with three masts and ‘modular’ sails. Pertaining to the latter, the sails of the ship could be adapted in accordance with the situation and requirement of the crew – with both lateen-rigged (caravela latina) and square-rigged sails (caravela redonda).

Suffice it to say, such levels of design flexibility allowed the caravel to be at the forefront of Portuguese exploration endeavors. One pertinent example would relate to the Niña and Pinta ships of Columbus that were instrumental in their journey to the Americas.

By the end of the 15th century, larger variants of caravels were built by the Portuguese, often as dedicated warships with better mobility. Some of these designs boasted four masts (with a combination of both square and lateen rigs), along with forecastle and sterncastle (although they were smaller than carracks).

Galleass (origins in late 15th century AD)

Designed as a compromise between the sail-driven larger ships and the oar-driven galleys, the galleass was fitted with a combination of oars (usually 32 in number) and masts (usually 3 in number). In essence, the warship was designed to have the better maneuverability of galleys while also having the volumetric capacity to hold heavy artillery.

Suffice it to say, many maritime factions adopted the design of galleasses, namely the Venetians who used them effectively in the Battle of Lepanto (1571), and the Ottomans who called their ‘hybrid’ ships mahons.

Unfortunately, over time, the limitations of such frigate-type galleasses came to the fore, especially because of their ‘compromising’ design. For example, most of the galleasses couldn’t carry the sturdy square sails because of the size of the galley-based hull. At the same time, the increased size, when compared to a standard war galley, didn’t allow the galleass to be as maneuverable as its oar-based predecessor.

Chebec (origins in 16th century AD)

A North African answer to the European warships with their broadsides (longitudinal side of the ship where the guns are placed), the chebec (or xebec – possibly derived from the Arabic word for ‘small ship’) was the evolved variant of the war galleys used by the Barbary pirates.

In response to the sails and guns of the larger European warships, the chebec was also designed to make room for broadside cannons. However, at the same time, the chebec was distinctly smaller and more streamlined in its overall form – especially when compared to the massive carracks (naos) of the Mediterranean.

Over the course of a few decades, the chebec warships completely ditched the oars, while relying on three massive lateen sails – thus making the complete transition from a galley to a sailing ship.

At the same time, their intricate design credentials like the adoption of large lateen yards, angular positioning of the masts, and longer prows made them speedier and more maneuverable than the bulky warships of the period. Interestingly enough, the effectiveness of the chebec warships led to their adoption in the 18th-century navies of both France and Spain.

Turtle Ship (origins in the late 16th century)

When the Japanese forces under daimyō Hideyoshi invaded Korea in 1592, they boasted of two significant advantages over their foes – their Portuguese-supplied muskets, and their aggressive tactic of boarding enemy ships (supported by cannon fire). However, Korean Admiral Sun-Shin Yi had an answer for these ploys in the form of the newly designed Turtle Boat (Geobukseon in Korean).

Constructed with the aid of newly raised private money, this relatively small fleet consisted of ships (with lengths of 120 ft and beams of 30 ft) covered in iron plates. The core frame was made from sturdy red pine or spruce, while the humongous structure itself incorporated a stable U-shaped hull, three armored decks, and two massive masts – all ‘fueled’ by a group of over 80 sinewy rowers.

However, the piece de resistance of the Turtle Boat was its special roof which consisted of an array of metallic spikes (sometimes hidden with straws) that discouraged the Japanese from boarding the ship.

This daunting design was bolstered by a system of 5 types of Korean cannons emerging from 23 portholes, that had effective ranges of 300 to 500 m (1000 ft to 1600 ft). And finally, the awe-inspiring craft was made even more intimidating – with a dragon head on the bow of the vessel that supposedly gave out sulfur smoke to hide the ponderous movement of the boisterous boat.

Galleon (origins in 16th century AD)

According to historian Angus Konstam, the early 16th century was a period of innovation for ship designs, with the adoption of better sailing rigs and onboard artillery systems. A product of this technological trend in marine affairs gave rise to the galleon – a warship inspired by the combination of both the maneuverability of caravels and the hefty nature of carracks.

To that end, the galleon was possibly developed as a specialized marine craft with a keel-up design dedicated primarily to naval battles and encounters, but also having some cargo-carrying capacity.

After the 1570s, it was the Spanish navy that took an active interest in developing their own version of the galleon – thus leading to the Royal Galleons of the Spanish Armada. These incredible warships ranged from humongous 1,000-ton (with 50 onboard guns) to 500-ton (with 30 onboard guns) capacities.

The weights were complemented by graceful designs, with a sharper stern, sleeker length-to-beam ratio (when compared to bulkier carracks), and a more effective hull shape for carrying artillery. However, by the early 17th century, the sizes of the Royal Galleons were trimmed down – to be increasingly used as escorts (and even cargo ships) for the highly profitable transatlantic trade routes.

As for the artillery on board the typical galleon, there were several varieties, including the larger canones (cannon), culebrinas (culverins), pedreros (stone-shotted guns), bombardettas (wrought-iron guns), and versos (swivel guns).

Among these, the pedreros – used as close-range anti-personnel weapons, and bombardettas – with their lower ranges when compared to bronze guns, were increasingly considered outdated by the 17th century. On the other hand, the versos, with their swivel-mount and faster breech-loading mechanisms, were effective and flexible for both solid-shot and grapeshot.

Schooner (origins in the 17th century)

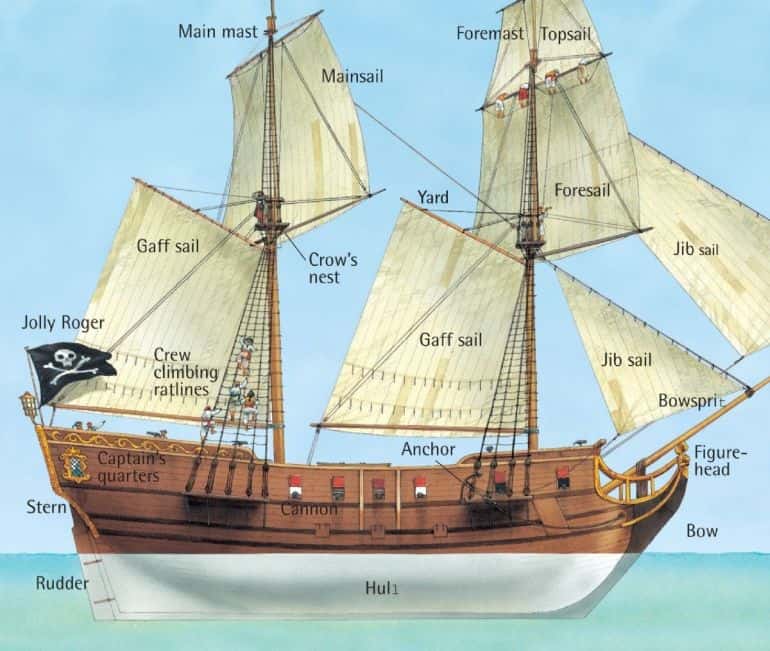

The schooner was typically defined as a relatively small marine vessel with two or more masts – with fore and aft sails on both these masts. Now while it was smaller than the general warships of the period, the schooner (and the even tinnier sloop) were the preferred craft commanded by the pirates who operated in the Caribbean region from around 1660-1730 AD.

This probably had to do with their relative inconspicuousness, greater speed, and better maneuverability – especially when compared to the bulky merchant ships. Simply put, the pirates of the Caribbean tended to prey on merchant vessels rather than the powerful warships that usually even moved in squadrons.

As for the ship-mounted guns, the sloop and larger schooner were typically equipped with the 4-pounder (also called the Canon de 4 Gribeauval), the lightest weight cannon in the arsenal of the contemporary French field artillery. These gun pieces weighed around 637 lbs and had a maximum range of over 1,300 yards. Larger pirate ships (like Black Bart’s Royal Fortune) obviously carried bigger guns, including the medium 8-pounder and heavy 12-pounder.

Conclusion – Ship of the Line

Unfortunately, in spite of the many modifications (both structural and organizational) made on the Spanish galleon, naval warfare in the decades of mid 17th century changed significantly in terms of formations and maneuvers.

To that end, in the following years, one of the widespread tactics adopted by many contemporary European navies related to the ‘line of the battle’. This entailed the formation of a line by the ships – end to end, which allowed them to collectively fire their cannon volleys from the broadsides without any danger of friendly fire.

The adoption of such tactics translated to ships being used as floating artillery platforms, thereby resulting in the design of heavier vessels with more guns – better known as the ‘ship of the line’. Suffice it to say, the sleeker warship (like the galleon) was ironically anachronistic, with the focus of shipbuilders once again shifting to the bigger warships with broadside artillery platforms.

Be the first to comment on "Powerful Types Of Warships From History: 7th Century BC – 17th Century AD"