Introduction

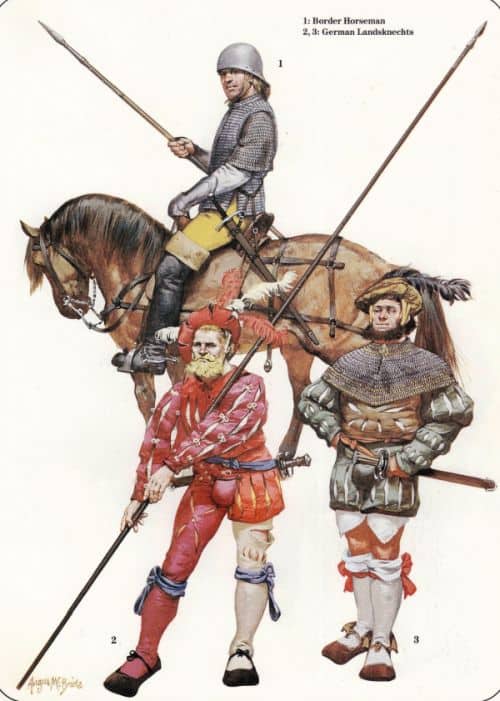

Possibly meaning ‘servant of the land’, the term Landsknecht generally denotes a specific German footsoldier (mostly pikeman) from the late 15th – mid 16th century who generally came from the mercenary background. Adopting the early Renaissance tactics of massed pikemen formations, partly influenced by the Reisläufer (Swiss mercenaries), these Landsknecht soldiers were not only formidable but also one of the most effective infantrymen of Europe during the aforementioned epoch.

Furthermore, quite interestingly, a part of their prowess was also fueled by their boisterous attitude and shocking dressing sense (for the period), thus landing them a fascinating place in the annals of military history.

Contents

- Introduction

- The Influence of Swiss ‘Motivation’

- Origins of the Landsknecht

- Recruitment and Organization of Landsknechts

- The Profile of a Would-be Landsknecht

- The Professional Soldier

- Arms and Armor of the Landsknecht

- Battlefield Role of the Landsknecht

- The Vibrant Costume of Landsknecht Soldiers

- The Element of Discipline and ‘Pike Court’

- The Intense Rivalry with Swiss Pikemen

- The Decline of the Landsknecht

- Honorable Mention – The Forlorn Hope

The Influence of Swiss ‘Motivation’

To understand the origins of the Landsknecht, we must first go through the short history of their predecessors (and later rivals) – the armies of the Helvetic Confederation (basically a coalition of cantons and city-states that later made up the union of Switzerland).

According to historian John Richards, these militiamen of the Alps were adept at skirmishing while also being well trained at the use of pikes, short swords, and maintaining cohesive formations – possibly as a result of small-scale but frequent border conflicts (as opposed to long drawn total wars).

Beyond their martial skills, the young men of the region were further known for their adventurous spirit and even daredevilry – so much so that groups of such impressionable men formed the saubannerzug. These bands of saubannerzug (the banner of the pig or foot) almost functioned as ruffian gangs – but imbued with an effective command structure and proper tactics.

Furthermore, the city-states tended to employ locally famous noblemen (schultheiss) or other veterans to command units of Swiss militias, thereby signifying the provincial yet highly efficient version of easily-musterable armies.

In essence, the effectiveness of these Confederate armies not only stemmed from their inclination towards pike drills and martial skills but also from their sheer motivation to fight alongside their neighbors, friends, and even family members.

So, during times of war, the bands were easily organized and then joined to make larger forces (numbering around 10,000 men) – which were further streamlined with dedicated divisions and battlefield roles. And it was this intrinsic nature of cohesiveness that allowed the Swiss Confederate armies to score astounding victories over their far richer and better-equipped opponents, like the Burgundians in the 15th century.

Origins of the Landsknecht

An interesting political development in the late 15th century allowed the Holy Roman Empire to gain control of Burgundy (which lost its own king in 1477 AD). Simply put, it brought forth the Empire close to the domains of both the Helvetic Confederation and France – but the heir to the throne, Maximilian I, wisely chose the military ‘influence’ of the former.

In fact, one of his crucial acts as a commander was to defeat an encroaching French force of knights and men-at-arms with an army of mostly pikemen. Suffice it to say, he was greatly inspired by the effectiveness of the pikemen, namely the famed footsoldiers of the Confederate armies.

On the practical side of affairs, the Holy Roman Empire was beset on its eastern flanks by the Ottoman Turks and troubled on its western flanks by France. So as a solution, the realm needed readily available troops who were already motivated and even trained to some degree.

Fortunately for the Empire, the southern German states with a high population density facilitated the ‘supply’ of young men who were eager for military action and booty. Moreover, the lingering border clashes already attracted droves of mercenaries from regions ranging from the Rhine, Alsace, Helvetic Confederation, and even Scotland.

Maximilian, on ascending the throne in 1486 AD, possibly recruited the first Landsknecht soldiers from these various mercenary pools and German communes. By 1488 AD, many of the Landsknechte (the plural term for Landsknecht) were officially trained, and one unit, known as the ‘Black Guard’, was possibly counted as the elite among these footsoldiers.

By as early as 1490 AD, the emergent Landsknechte proved their worth in battles by successfully conducting actions and winning encounters against the Hungarian Kingdom in neighboring Bohemia.

Recruitment and Organization of Landsknechts

Almost mirroring the recruitment of the Swiss militias (who fought against Burgundy), the Landsknecht soldiers were ‘enticed’ into the ranks by men of influence, power, financial means, and even personal charisma. Some of these men, known as obrist (colonel), were basically military veterans with ‘street smart’ business experience – and as such, they performed a crucial role that bridged the gap between a commanding officer and a paymaster.

As was often the case, the greater nobles and even the emperor were short of expendable cash during times of war; and in such chaotic scenarios, the obrist, with his business acumen, stepped up to maintain a fighting unit of Landsknechte – who were paid by raising bank loans and even from the colonel’s own pocket.

And while this may seem to be a risky endeavor in terms of money, over time, the obrist’s own pay or commission (directly ascertained from the Imperial revenues after the conflict) more than made up for temporary financial doldrums. In terms of numbers, a regular Landsknecht was paid around 4 guilders per month, while for a high-ranking obrist the figure reached 150 times that value.

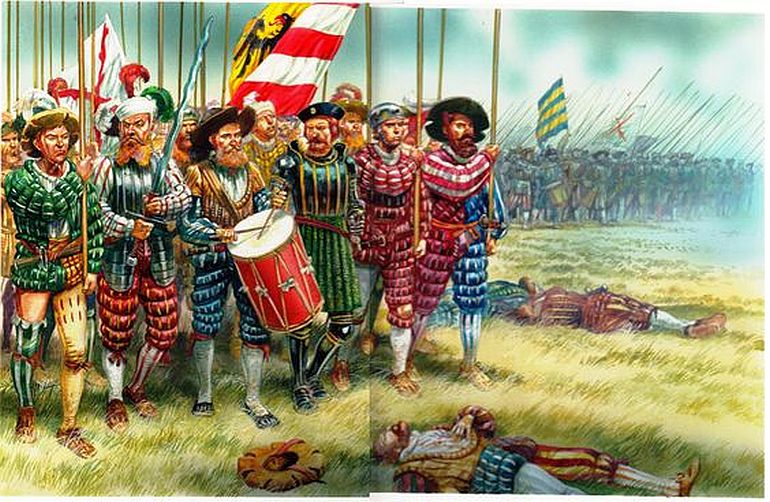

Consequently, the importance of obrist was rather reflected by his autonomous stature within the army, regarding how he had freedom in recruiting his regiment (usually numbering 3,000 – 5,000 men, but sometimes even reaching 10,000) and employing the other officers. This, in turn, allowed for an almost privatized military system that could sustain (to some degree) Landsknechte manpower and logistics during times of conflict and delay of Imperial payment.

These regiments were further divided into the Fähnleins (companies) – which were headed by the Hauptmann (Captain), and the command structure was aided by a group of other ‘officers’, including the lieutenants and Fähnriche (ensigns).

The Profile of a Would-be Landsknecht

The Burgundian army that suffered its defeat at the hands of the Helvetic Confederation was an adequately equipped and well-trained army. In spite of such qualities, they were outmaneuvered by the Swiss Confederate militias because of the latter’s sheer sense of cohesiveness, morale, and motivation to fight as solid formations of footsoldiers.

Maximilian’s Landsknechte were certainly modeled after the Swiss – and this is even reflected in the backgrounds of the young men who join the ranks of well-drilled pikemen and footsoldiers. For example, as opposed to peasants, it was the middle-class city apprentices who were keener to join the Landsknechte, possibly because of stricter guild laws that dissuaded them from having their own workshops.

Similarly, many areas of Germany and Austria had a population explosion – so much so, that even the younger ‘third’ sons of wealthy families, denied their inheritance and enticed by both pay and potential plunder, were known to have joined the Landsknecht banners.

To that end, as historian John Richards mentioned (in his book Landsknecht Soldier 1486 – 1560), the extremely poor folks were rather ‘weeded out’ since the Landsknecht had to initially pay for his equipment which cost around 14 guilders. He covered this cost from his monthly allowance (sold) of 4 guilders, which was higher (at least in the initial years) than the income of the stonemasons and laborers working in the cities.

The Professional Soldier

As mentioned in the earlier entry, the ranks of the Landsknechte were mostly formed by the relatively well-off, as opposed to the poorer sections of the society. But economic means alone didn’t qualify one for employment; one also had to prove his fitness and social bearing to the recruiting obrist.

Furthermore, ‘employment’ is the keyword here. Simply put, befitting their mercenary status, the Landsknecht soldier was perceived as an employee of the regiment who was provided with his bestallung brief (‘letter of appointment’).

This document not only highlighted his monthly payment and length of service but also mentioned the terms of the engagement, judicial codes (‘articles of war’), and names of his obrist and other commanding officers (or rather the equivalent of officers, like the field-colonel, penny-master, and other sergeants).

Interestingly enough, the Articles of War laid out some guidelines pertaining to the prescribed conduct of the Landsknecht soldier. For example, he was expected to protect the women, children, old people, and church properties, while also expected to pay for his goods in friendly territories.

As for his soldierly discipline, the Landsknecht was only allowed to plunder when told to do so and expected to limit his gambling and alcohol consumption to manageable levels. Furthermore, he was not to desert or run away from the battlefield on pain of execution, even if his payment was delayed (till two weeks or some vague timeline).

Arms and Armor of the Landsknecht

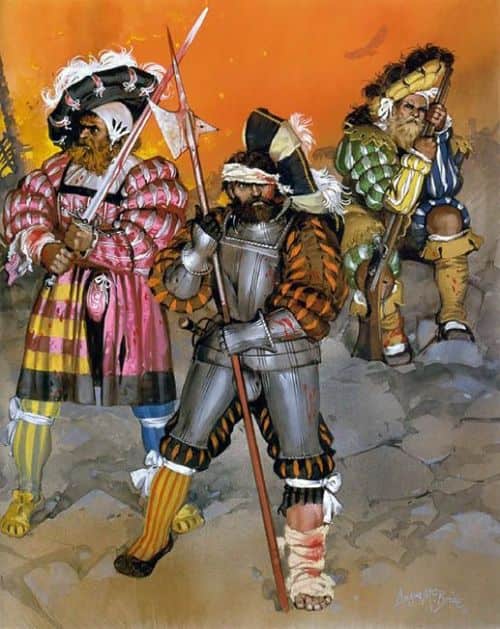

In terms of armor, the regular Landsknecht soldiers (or pikemen) went rather light with simple breastplates with tassets (thigh guards) and steel skull caps, thus allowing them to focus on handling larger (14 – 18 ft length) weapons like pikes – usually made of ash staves with steel heads.

On the other hand, the experienced Landsknecht, known as Doppelsöldner (‘double pay man’) – whose group formed the core of the formation, was armored more heavily and armed with the vicious zweihänder (two-handed) swords, poleaxes, Kriegsmesser longswords, and halberds.

Such varied weapon types were accompanied by side arms, including the renowned katzbalger (cat skinner) swords with S-shaped quillons, crossbows, and later arquebuses. Among these, the katzbalger was perceived as the iconic weapon of the Landsknecht – so much so that even contemporary Swiss illustrators depicted such weapons to differentiate the Landsknecht from his rival, the Reisläufer (Swiss pikeman).

Battlefield Role of the Landsknecht

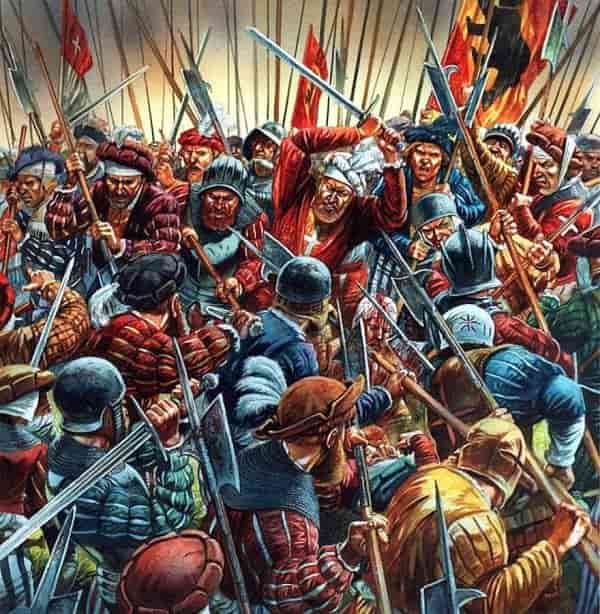

In terms of a general role, the Landsknecht soldiers mostly comprised the pikemen – and thus their standard battle formation pertained to the use of blocks of massed pikemen, much like their Swiss predecessors (and rivals).

However, it can be argued that unlike the Swiss (or rather Confederate soldiers), the Landsknechte were not overly dependent on the melee capacity of their pikemen. In that regard, we know of Landsknechte preferring to hold their pikes at shoulder height, whereas the Swiss tended to hold them overhead at an angle for better offensive maneuvers.

To that end, the massive blocks of Landsknecht pikemen were often accompanied (or flanked) by dedicated double ranks of halberdiers, swordsmen, and arquebusiers (who replaced the earlier crossbowmen) – and together such ‘mixed’ formations were reminiscent of the igel (hedgehog) pattern. During the reign of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, the Landsknecht pikemen and swordsmen were aided by the Spanish arquebusiers, thereby resulting in formations that were at once defensive and yet tactically dynamic.

In essence, this (somewhat) solved the outdated and rather inflexible maneuver of massed pikemen advancing and deciding battles – since such footsoldiers were easy targets for the enemy artillery (especially in open battlefields).

Consequently, there were occasions when Spanish cannons focused on the enemy Swiss halberdiers, while the Imperial Landsknechte were used to mop up the remnants of the tattered foe. In other scenarios, like in the Battle of Pavia (1525), the Landsknechte also proved their mettle in offensive tactics by advancing into enemy positions in spite of suffering significant casualties.

The Vibrant Costume of Landsknecht Soldiers

While the katzbalger (cat skinner) swords were symbolic items of the Landsknecht regiments, in terms of visual flair, it was always their seemingly garish sense of fashion that stood out in the military scheme of things. In fact, their florid, colorful attires (often bordering on the gaudy), flamboyant caps, and appetite for violence and rambunctious pursuits were perceived as markers that set them apart from other soldiers.

However, one could argue that these ‘patterns’ were part of Landsknecht’s persona, so as to prove how his mercenary status and martial prowess made him independent from other military institutions.

In terms of influence, historians also agree that their clothing sense was partly inspired by the Swiss mercenaries. But there was a deliberate direction of excess associated with the dressing sense, with slashed doublets, shirts of multifarious hues with puffed sleeves, vibrant hoses (sometimes with exposed knees), and prominent codpieces – complemented by feathered beret-type hats and broad flat shoes. Such attires were meant to shock people, thus serving as striking visual indicators that unmistakably identified them as the famed Landsknechte.

The Element of Discipline and ‘Pike Court’

By virtue of their special ‘independent’ status (accorded to them by Emperor Maximilian I), the Landsknechte didn’t fall under the jurisdiction of civil laws. However, the Landsknecht was subject to a particular set of guidelines and military laws that underlined the discipline in both their camps and on the battlefield.

In theory, such military laws and courts were seen as extensions of the collective will of the Landsknecht regiment – and thus the ‘courtrooms’ (basically benches set up in open air) were only attended by the Landsknechte themselves (in order of their ranks). Interestingly enough, much like in our modern times, both the prosecutor and the defendant were entitled to two counselors.

As historian John Richards mentioned, in one of the interesting examples of self-justice, known simply as the ‘pike court’, the judgment was made by open voting within the regiment. Usually reserved for serious charges (like bringing disrepute to the regiment), the outcome for the defendant was either acquittal or death – and thus the entire process of voting and carrying out the sentence was completed in a day.

Incredibly enough, the voting from the soldiers was made on the basis of three separate recommendations – each formulated by groups of Landsknechte who had studied the entire case. And if the defendant was found guilty of his serious charges, he was solemnly ordered to run between two formed lines of Landsknechte while asking for their forgiveness.

After doing so, he would reach the provost at the end, and the provost would symbolically strike him thrice on his right shoulder. And then he would again have to run between the lines, with the accompaniment of drums and fifes, until his comrades executed him with the tip of their pikes.

The Intense Rivalry with Swiss Pikemen

It should be noted that when the Landsknecht regiments were still in the process of being formed as an answer to conventional armies (by circa late 15th century), the most sought-after mercenary units in Western Europe pertained to the Swiss pikemen, who proudly called them themselves Eidgenossen (Confederates).

In fact, many of the early Landsknecht units were trained by instructors from the Helvetic Confederation, while few of such regiments even had members from the distant Swiss cantons. But with the full-fledged emergence of the Landsknechte, there were several units who would openly showcase their distaste for the Reisläufer (Swiss mercenaries).

The rivalry between these famed footsoldiers inevitably turned into armed conflict when the Holy Roman Empire went into a war (Swabian War) with the Helvetic Confederation in 1499 AD. The intense battles, especially when pitted against each other where the quarter was neither asked for nor given, resulted in encounters known as schlechten krieg or ‘bad wars’.

Such conflicts were interspersed with elements of psychological warfare and propaganda – with both sides engaging in insults and slurs against each other (that were even distributed by leaflets).

Some examples from the Landsknecht side pertain to derogatory terms like milchsufer (milk boozer), chueschnaggler (cow cuddler), and chueschweizer (cow swiss). Interestingly enough, over time, the term ‘schweizer’ stuck around, thus giving way to the name Schweizerland (‘land of cowherds’) or Switzerland – denoting the lands of the Helvetic Confederacy.

The Decline of the Landsknecht

Unfortunately, the very nature of the Landsknecht soldiers, pertaining to their mercenary status and relatively easy availability, proved to be their downfall. To that end, by the late 16th century, many areas of Germany continued to go through a phase of population explosion – and as such, an even greater number of folks joined the ranks of mercenary companies.

At the same time, inflation rose, while Landsknecht payments remained constant (at 4 guilders), thereby eroding the rather ‘exclusive’ nature of the regiments. Consequently, unwanted elements, including even criminals, sought to gain employment with such companies.

Furthermore, political instability and the proclivity to fight only for ‘money’ (as opposed to security concerns) led to a general mistrust of mercenaries – so much so that some cities even forbade their recruitment. And as payments got stifled, roving bands of unemployed Landsknechte took to general lawlessness and banditry.

And finally, advancements made in gunpowder technology and artillery further relegated the need for massive formations of pikemen and foot soldiers. Such tactical changes were reflected in the last decade of the 16th century, with mobile cavalry forces (like the Hussars) and devastating gunpowder companies functioning as crucial units that tended to decide the outcome of many open battles.

Honorable Mention – The Forlorn Hope

The Forlorn Hope, known as Verlorene Haufen (literally translating to ‘lost group’) in German, was a gutsy group of soldiers chosen from the Landsknechte, and they were primarily tasked with breaking the enemy formations. In essence, these daredevils, often armed with heavy two-handed swords, formed up their own loose ranks in the front of the main body and then desperately charged into the enemy pikemen to shock and awe them.

Conversely, they were also the first to receive the charge of the foe when the opponent soldiers were on the offensive. Now considering the sheer brutality of this perilous maneuver, it comes as no surprise there was always a dearth of volunteers in the Forlorn Hope.

Some of the adventurous and stouthearted, in a bid to earn their ‘double-pay’, may have taken it upon themselves to form the front ranks. With the passage of time, even criminals with death sentences were inducted into the Verlorene Haufen. Consequently, symbolizing the gritty, resolute, and deadly nature of their tactics, the Forlorn Hope of the Landsknecht regiments were known to have carried the red Blutfahne (‘Blood Banner’).

Book Reference: Landsknecht Soldier 1486 – 1560 (By John Richards)

Online Sources: MilitaryHistoryNow / Britannica / Military.Wikia

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork, or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "Landsknecht: The ‘Garishly’ Effective Footsoldier Of 16th Century"