Introduction

Quetzalcoatl is arguably (and rather uniquely) the most renowned of all mythical entities from Aztec mythology, whose legacy has survived the rigors of time and foreign influence. Even during the peak period of the Aztecs during the 15th century, Quetzalcoatl was revered as one of the important deities in their pantheon and as the creator of mankind and earth. In essence, he was often venerated as an ancestor god who in the mythical narrative ‘carved out’ the lineage of various Mesoamerican groups.

Contents

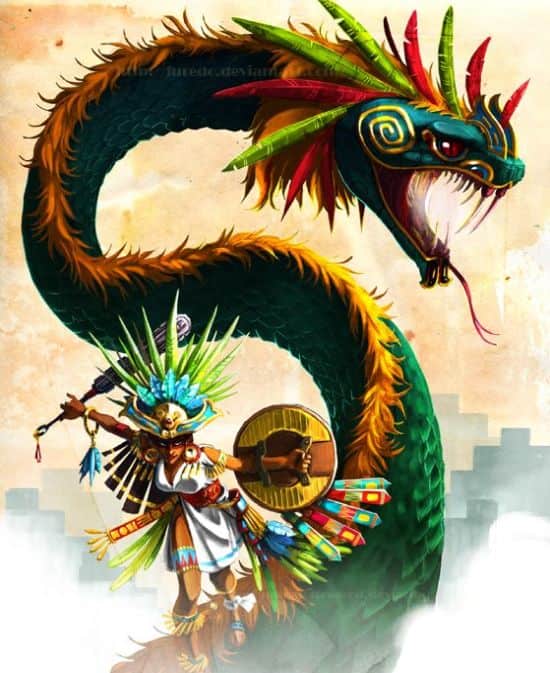

Depictions of Quetzalcoatl – Feathered Serpent Iconography

The very term Quetzalcoatl (or Quetzalcohuātl in Classical Nahuatl) means ‘feathered serpent’. In the Nahuatl language, quetzalli roughly means ‘long green feather’, later associated with the ‘emerald plumed bird’, and coatl refers to a serpent. Unsurprisingly, many depictions of Quetzalcoatl pertain to a serpent, with the probable earliest known representation of the god found at the Olmec site of La Venta.

The stela, dating from some time between 1200 – 400 BC, portrays a serpent rearing its head behind a person (possibly a priest). More elaborate depictions of the feathered serpent version are found in the six-tiered pyramid built in the god’s honor at Teotihuacan, dating from circa 3rd century AD.

Similarly, the Maya serpent imagery from the Classic period (circa 250 – 830 AD) is also found in many Mayan sites. According to researchers, the feathered serpents (pertaining to the Classic Maya serpent iconography) probably symbolized the sky or in some cases planet Venus.

However, given the diversity of cultures in Mesoamerica and the ever-evolving nature of myths, Quetzalcoatl was also portrayed in forms that went beyond the morphology of the plumed serpent. For example, there are a few representations of Quetzalcoatl that are distinctly human in form – from the site of Xochicalco (a pre-Columbian site that Mayan traders settled). These depictions date from circa 700 – 900 AD.

Quite incredibly, the ‘human’ nature of Quetzalcoatl influenced the later Toltec rulers, so much so that they might have even venerated and equated Quetzalcoatl to a king. To that end, the feats of the 10th-century Toltec king Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, who was said to have ruled over the mythic-historic city of Tollan, are almost inseparable from the legends of the god himself.

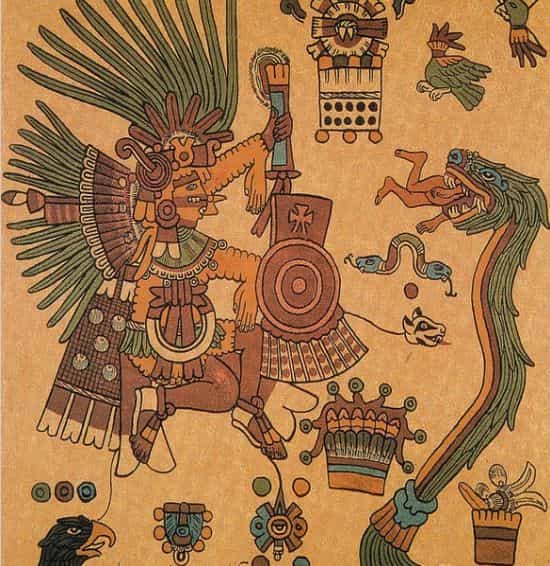

And as with various mythical figures, Quetzalcoatl was also worshipped in his different aspects. For example, in the aspect of Quetzalcoatl-Ehécatl, the god was depicted with a duckbill mask protruding with fangs and shell jewelry known as the ehecailacocozcatl (‘wind breastplate’).

As for his aspect of Quetzalcoatl-Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli, the Mesoamerican deity was portrayed with an ominous black facemask, complemented by an opulent headdress and darts representing the rays of the morning star.

Origins and History of Quetzalcoatl

As we fleetingly mentioned in the earlier entry (referring to the Olmec depiction of the serpent god), the cult of the serpent in Mesoamerica predates the Aztecs by almost 2,000 years. The worship of the ‘Feathered Serpent’ as a definite deity possibly started in Teotihuacan, the largest city in the pre-Columbian Americas, by circa 1st century AD.

After the fall of Teotihuacan by circa early 7th century AD, the Feathered Serpent cult didn’t stop but rather spread to other Mesoamerican urban centers, including Xochicalco, Cholula, and even Chichen Itza of the Maya people – as could be discerned from the iconography of the period. Simply put, while it was not the same feathered serpent deity worshipped by all the factions, there was certainly continuity in the symbolism of feathered snakes found across the ancient Mesoamerican cultures.

Thus the ‘Feathered Serpent’ was also known as Kukulkán to the Maya of Yucatan (possibly having its origins in Waxaklahun Ubah Kan, the War Serpent or the even older Vision Serpent) and Gucumatz (or Qʼuqʼumatz) to the Quiché of Guatemala. And as we described before, the Toltec rulers continued the tradition of venerating Quetzalcoatl through their own mythic-historical association of rulers with the deity.

For example, there might have been a Toltec warlord with the namesake Quetzalcoatl, possibly also known as Kukulkán, who invaded the Yucatan in the early Post-Classic Period (circa 900 AD). Similarly, another legendary Toltec ruler Topiltzin Ce Acatl Quetzalcoatl was hailed as the son of Mixcoatl, a renowned Chichimeca warrior.

Interestingly enough, Mixcoatl was primarily perceived as the god of the hunt in the later Aztec religion. In essence, over the course of centuries, the Nahua-speaking tribes (of Aztec culture) would adopt many of the legends of Quetzalcoatl (along with other Toltec myths) and mix them with their own native folklore. This gave rise to the ubiquity of the mythical ‘Feathered Serpent’ and its motifs in the Aztec pantheon of gods by circa 15th century AD.

Lineage and Myths of Quetzalcoatl

Counted among the most important Aztec gods (and Mesoamerican divine entities), Quetzalcoatl is regarded as the son of the creator deity Ometecuhtli (in some stories, Quetzalcoatl is regarded as the son of the virgin goddess Chimalman). He was also venerated as the creator of mankind and earth in the Aztec pantheon.

In one version of the Aztec creation myth, the world was created and destroyed four times (each age associated with the sun). Some of the tumultuous episodes were borne by the fighting between Quetzalcoatl and his brother Tezcatlipoca (‘Smoking Mirror’).

Ultimately during the Fifth Sun, Quetzalcoatl was successfully able to retrieve the human bones from the underworld Mictlan (guarded by the realm’s ruler – Mictlantecuhtli) that were infused with his own blood and corn to once again ‘regenerate’ mankind.

In another myth, the god along with his brother Tezcatlipoca fashions the earth out of Cipactli, a female serpent-like monster. Consequently, her hair and skin give way to trees and flowers, while her eyes and nose account for the caverns and springs.

However, given the violent loss of her physical form, the monster (now embodying the earth) thirsts for blood and hearts – thus alluding to the grisly practice of human sacrifice. Quite interestingly, in some Aztec traditions, Quetzalcoatl opposes human sacrifice possibly for this very same reason – because the practice goes against the legacy of the gods defeating the bloodthirsty monster.

Talking of sacrifice, in yet another myth, Tezcatlipoca tricks Quetzalcoatl into getting drunk on pulque (an alcoholic drink fermented from the sap of the maguey plant) by masking it as a medicinal drink. The inebriated god then goes on to flirt with his own sister – the celibate priestess Quetzalpetlatl, thereby hinting at some form of incest.

Waking up the next morning, the remorseful Quetzalcoatl willingly sets himself on fire (thereby sacrificing himself), and consequently, his ashes and heart rise up to the sky to transform into the radiant morning star (Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli or aspect of Venus).

Attributes of the Feathered Serpent Deity

The question can be raised – why was the deity particularly associated with a serpent? Well, according to some scholars, the snake in its most basic form in Mesoamerican culture might have represented the earth and the vegetation. Archaeologist Karl Taube hypothesized that the feathered serpent, by virtue of its ‘evolved’ morphology, may have been associated with fertility as well as the intricate political classes of the region.

In Aztec circles, Quetzalcoatl probably also symbolized one section of agricultural activities that pertained to the very renewal of vegetation, while also being linked to the morning star or Venus (sometimes referred to as the evening star, symbolized by his twin brother Xolotl). Consequently, in the Aztec ritual calendar, Quetzalcoatl was linked with the cycle of the year Ce Acatl (One Reed).

Talking of twins, interestingly, the twin Aztec high priests of the Templo Mayor (the main temple of Tenochtitlan – the capital of the Aztecs) were given the title of Quetzalcoatl Tlamacazqui. To that end, Quetzalcoatl was considered the patron deity of the Aztec priesthood, thus being also associated with learning.

Interestingly enough, the duality of Quetzalcoatl and his brother Tezcatlipoca mirrors the mythical narrative of light and darkness. In that regard, Quetzalcoatl was often venerated as the god of light, rain, justice, mercy, and wind (along with even knowledge, books, and poetry); while contrastingly, Tezcatlipoca was considered the god of night, deceit, sorcery, and the Earth.

Another legacy, possibly borrowed from the earlier Toltecs, made Quetzalcoatl the patron god of priests, thus alluding to the symbol of death and resurrection. Furthermore, both Quetzalcoatl and his brother Tezcatlipoca were honored as Ipalnemohuani, meaning ‘by whom we live’, with the title giving credence to their statuses as creator gods of ancient Mexico.

Hernán Cortés and Quetzalcoatl

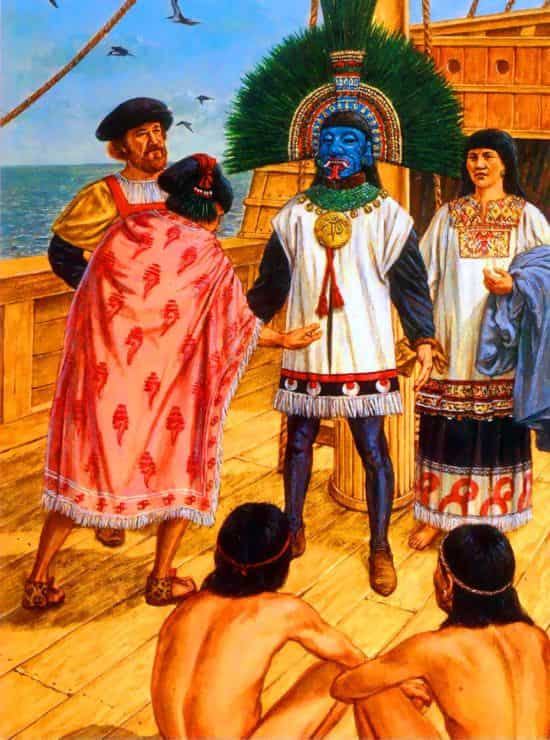

As we discussed before, Tezcatlipoca was associated with night and darkness, whereas his equal yet opposite Quetzalcoatl was associated with light and thus possibly referred to as the White Tezcatlipoca. In some myths, Quetzalcoatl grows a beard and goes on to wear a white mask, thereby hinting at his erroneous representation as a white-bearded god. And it is this latter characterization that has been debated in academic circles.

According to a previously held conventional theory, the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma II regarded the arrival of the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés on Mexican shores (circa 1519 AD) as the return of Quetzalcoatl, given his ‘white-bearded face’. However, this connection of Quetzalcoatl-Cortés is not really found in any native document that is devoid of the post-Conquest Spanish influence.

Furthermore, historians have found only scarce evidence of such a foretelling of Quetzalcoatl’s return in pre-Hispanic traditions. Simply put, the narrative of Cortés fulfilling his role as the mythical Quetzalcoatl in the conquest of the Aztec territories might have been propaganda from the Spanish side (to provide a veneer of pretext for their conquests) or an excuse from the Aztec side (to hide their inability to stop the conquistadors).

Endurance of Quetzalcoatl’s Legacy

Interestingly enough, from the historical perspective, even decades before the arrival of the Spanish, the Aztec Empire fought against a tenacious enemy in the form of a confederacy of Eastern Nahuas, Mixtecs, Zapotecs, and other associated tribes under them.

The confederacy was known for both coveting and maintaining a major pilgrimage center at Cholula – the city dedicated to the worship of Quetzalcoatl. In essence, Quetzalcoatl was regarded as the ‘unifier’ deity who was to be venerated across tribal lines, on the basis of common social and political grounds of the ancient Mesoamerican culture.

This confederacy went on to provide logistical support to the Spanish conquistadors in their time and even went on to take control of the symbolic Cholula from a pro-Aztec faction. Over the course of years, many of their leaders gained important commercial routes and forged crucial economic ties with the Dominican order of the Spanish Imperial provinces in Mesoamerica.

In the twist of irony, such ties with the foreigners rather bolstered their autonomy as native powers. This in turn allowed for the preservation of indigenous traditions related to Quetzalcoatl for centuries to come. And lastly, the complex legacies of Quetzalcoatl in religious circles were also unexpectedly preserved by fringe groups, like some members of The Church of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons).

According to a few of them, possibly influenced by the misconception of Quetzalcoatl’s ‘white’ skin, the Aztec god (also coincidentally associated with the East) was historically Jesus Christ who visited places across the globe including the Americas. However, it should be noted that officially the Mormon Church doesn’t endorse such a perspective, with one noted Mormon author categorizing this peculiar association as folklore.

Online Sources: McGill University / LACMA / World Digital Library / MexicoLore

Featured Image: Artwork by GENZOMAN (DeviantArt)

Be the first to comment on "Quetzalcoatl: History and Mythology of the Aztec ‘Feathered Serpent’ God"