Introduction

In popular culture and fantasy genre, we are accustomed to depictions of undead, dragons, elves, and dwarves. Interestingly, most of these creatures have their own versions (and even origins) in Norse mythology – from a patchwork of oral traditions and local tales that were conceived in both pre-Christian ancient Germania and early medieval Scandinavia.

Most of these myths are accessible to us through the works of literature like the Prose Edda, assumed to be written by the Icelandic historian Snorri Sturluson, circa 1220 CE. The other crucial literary work composed in Old Norse relates to the Poetic Edda.

As its name suggests, the compilation consists of poems dating from circa 1000 – 1300 CE. Most of the collections contain text from the Codex Regius (Royal Book), an Icelandic medieval manuscript dating from circa 1270 CE.

The Codex Regius in itself is considered one of the most important extant sources for both Norse mythology and Germanic legends. To that end, let us take a gander at 20 such fascinating creatures and monsters from Norse mythology through both the cultural and historical lens.

Contents

List of Norse Mythology Creatures

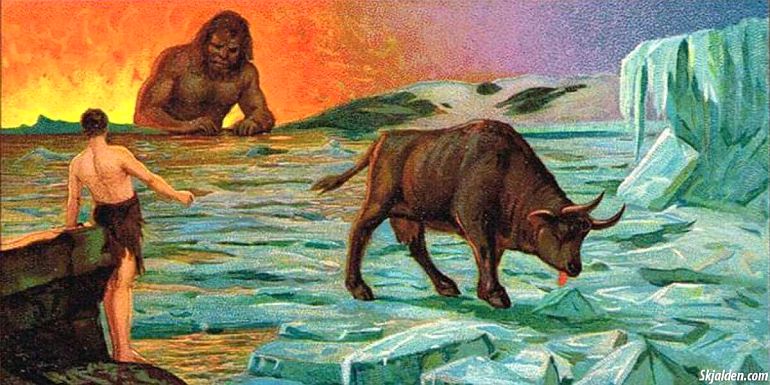

Audhumla

Audhumla (or Auðumbla) was the primeval cow in Norse mythology. As mentioned in Gylfaginning (the first part of Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda), she was responsible for sustaining the primordial frost giant Ymir – who is fed with the milk from Audhumla. Ymir, in turn, gave birth to a host of mythical creatures and divinities, including the first male, female, and six-headed monster.

Audhumla, the Cow, also played an essential part in Norse creation myth by revealing Buri – the ancestor of all Aesir Norse gods. She did so by licking away the salty rime rocks. As abstracted from the Prose Edda – “The cow licked salty ice blocks. After one day of licking, she freed a man’s hair from the ice. After two days, his head appeared. On the third day, the whole man was there. His name was Buri, and he was tall, strong, and handsome.”

Buri was the grandfather of Odin – the chief among all the Aesir gods and goddesses. As for Audhumla, she was only mentioned once in another subsection of Prose Edda (Nafnaþulur), in reference to cows. In terms of history, such cow-oriented deities are also found in other mythologies, like Hathor in Egyptian mythology and Hera (‘the cow-eyed’) in Greek mythology.

Draugr

The Draugr (or Draug) is simply a Norse version of an undead creature. However, unlike the zombies presented in typical popular culture, the Draugr were often depicted as hideous yet magically powerful creatures of Norse mythology who often possessed superhuman strength and size.

So unlike a ghost, the draugr had a corporeal body of a reanimated corpse, which made it akin to a revenant (or even similar to a barrow wight from the works of J.R.R. Tolkien). However, in Norse folklore and myths, the definition of a draugr is pretty vague, with some characters like Kárr inn gamli (‘Kar the Old’) being specifically called a draugr, while others like Glámr called a troll (or a vampiric creature of a cairn).

In any case, most folkloric traditions attest to the draugar (plural form of draugr), as undead creatures, having the sickly complexion of ‘corpse pale’ or even necrotic black. Pertaining to the latter, the Draugr of Thorolf in the Eyrbyggja saga was said to have skin that was black as death, reeking of decaying bodies, while his size was swollen to that of a huge ox.

Some draugar, like Þráinn (Thrain), were portrayed as having large claws, while others were noted to have the power to shape-shift, look into the future, and even swim through solid rock.

As for history, the Vikings were known to have taken ritualistic precautions during funerary rites to prevent the deceased from becoming a draugr who could wreak havoc on the living. For example, the toes of the dead were tied so that the body couldn’t move. In other instances, a pair of scissors were kept on the chest as a symbolic gesture of precaution.

Dwarves

Dwarves (dvergr in Old Norse) are represented as magical beings who were inherently skilled at smithing and crafting. One of the first known origin stories of the dwarves is found in Völuspá, the first poem of the Poetic Edda. Here it is mentioned how these beings were (possibly) created from the blood and bones of Ymir – the primeval giant who was sustained by Audhumla the Cow.

And since we are talking about the dwarves of Norse mythology, it should be noted that early Germanic lore never explicitly attested to the perceived short stature of dwarves. For example, four dwarves were believed to hold aloft the very sky in four cardinal directions.

However, Prose Edda does mention how the dwarves were dark, shortish (with the phrase – dvergr of voxt or “short like a dwarf”), and lived underground in Svartalfheim – which basically made them black elves. Some were even said to turn to stone in sunlight, much like the trolls of popular culture.

Irrespective of the blurred nature of physical traits, the dwarves, in Norse mythology, were responsible for creating incredible enchanted items, including the famed Mjollnir, the hammer of Thor; the unbreakable Gleipnir, the chain that bound the wolf Fenrir; the Skidbladnir, a ship of Freyr that always had favorable wind; and Gungnir, the runic spear of Odin.

Elves (Light Elves and Dark Elves)

Elves (álfr in Old Norse) are described as luminous beings who mostly resided in Alfheim (meaning Home), one of the Nine Realms of Norse mythology. Akin to what can be termed minor divinities, the elves were believed to have intrinsic magical powers and unsurpassed beauty.

Interestingly, as opposed to what we identify as an elf in modern fiction and popular culture, the ancient Germanic people had a more indistinct concept of the mythical being. For example, in the book Gylfaginning from Prose Edda, the elves are roughly categorized into Ljósálfa (light elves) and Dökkálfar (dark elves).

The former, dwelling in the blessed realm of Alfheim, were “fairer than the sun” to look at, with their delightful demeanor and healing powers. Contrastingly, the dark elves burrowed underneath the ground and were seemingly abrasive in their attitude. There is also mention of the Svartálfar (black elves or dusky elves) in the Eddas.

Some scholars have hypothesized that in view of the blurred aspects of minor divinities in Norse myths, the dark elves (or more specifically the black elves) were simply reinterpretations of the dwarves (as discussed earlier). Furthermore, in Germanic culture, there were also overlaps in ancestor worship and the veneration of elves, thus suggesting how elves were perceived as exalted versions of humans.

Fafnir

Fafnir was a fearless dwarf in Norse mythology who tragically became a greedy dragon cursed by the allure of gold. As mentioned in the Icelandic Norse myth Volsunga Saga, Fafnir was originally a brave dwarf with a very strong right arm. Consequently, he was chosen by his father, the Dwarf king Hreidmar, to guard their house bedecked with gold and precious gems. His other four brothers were Regin, Ótr, Lyngheiðr, and Lofnheiðr.

Unfortunately, the life of the dwarfs turned horribly wrong when Ótr was mistakenly hunted and killed by Odin and Loki because he resembled an otter during the day. The events took an even more grievous turn when Loki ransomed Odin (who was captured by the dwarfs) with the cursed gold of Andvari and the ring Andvaranaut.

The curse led to Fafnir killing his own father and taking over the immense hoard of gold and jewels. It also transformed him into a greedy and loathsome poison-breathing dragon that fled into the wilderness to jealously guard his ill-gotten riches.

However, his other brother – the dwarf smith Regin, who raised Sigurd – the Germanic folk hero, plotted for revenge. Thus the smith sent the hero Sigurd on a dangerous mission to kill Fafnir. Sigurd, aided by his sword Gram, and the advice of Odin, did successfully slay Fafnir, But things once again turned nasty. After the death of the dragon, Regin, in turn, was filled with lust for the cursed gold, until he was also killed by Sigurd.

Fenrir

Fenrir (or Fenrisúlfr, meaning Fenris-Wolf) is probably the most famous wolf in Norse mythology. Destined to break free of his enchanted fetters during the calamitous Battle of Ragnarök, Fenrir is foretold to kill Odin himself. However, it is also foretold that the monster, in turn, will be slain by Odin’s son Víðarr – the silent god of vengeance.

In Norse myths, Fenrir was born from the union of the god Loki and the giantess (jötunn) Angbroda. His other monstrous siblings were the World Serpent Jormungand and the Ruler of the Underworld (or Niflheim) Hel. And interestingly, while these two were kept at bay by the Aesir, the vicious Fenrir was directly guarded by the Norse gods under the watchful eye of Odin.

And it was here that Fenrir was bound by the dwarf-made magical fetter Gleipnir – until the end of time and the arrival of the foretold Ragnarök. However, even while binding the giant wolf, the war god Tyr had to sacrifice his right hand, which was violently bitten off by Fenrir in his rage.

Moreover, Fenrir’s own children – the giant wolves (or wargs) Sköll and Hati Hróðvitnisson, are foretold to swallow the sun and the moon respectively (or vice versa) during the cataclysmic clash of Ragnarök that will end the present world cycle.

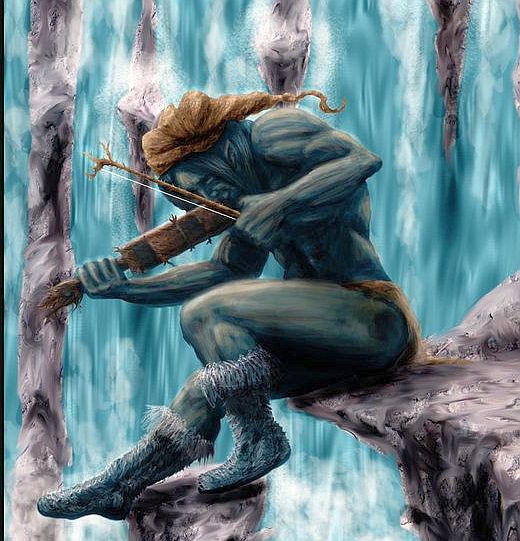

Fossegrim

Fossegrim (or Strömkarlen) is traditionally associated with the folklore of the Scandinavian countryside (as opposed to just Norse mythology). Usually, portrayed as a male water spirit residing by the river banks or nooks of waterfalls, the fossegrim is said to have incredible skills as a fiddler.

The musical talent of this creature has to do with the innate command over the blissful sounds of the forest, wind, and water. And weirdly enough, the lore suggests that the Fossegrim can even teach their skillset to adventurers – only on the condition of offerings being made on certain days of the week. These favored ‘gifts’ range from live white goats to smoked mutton delicacies.

As for appearance, Fossegrim and related creatures in Norse mythology were usually depicted as graceful males dressed rather haphazardly in nature’s garb. However, much like the Sirens of Greek mythology, some of the malevolent beings tended to lure victims (both women and men alike) to their doom. While other stories mention how the Fossegrim tended to be completely harmless.

Hugin and Munin

The prevalence of raven-related imagery in both Norse mythology and popular culture alludes to death (or forewarnings of death). To that end, the Germanic people associated Odin with various (and often antithetical) aspects, ranging from wisdom, and frenzy to even death. Pertaining to the latter, Hugin and Munin (Huginn and Muninn) were the two ravens of Odin perched on his shoulders – who often heralded the carnage of battles and warfare.

In the metaphorical sense, the ravens, as carrion birds, ‘fed’ on the ‘offerings’ (the slain) of the battlefield – thus suggesting how the fallen warriors, especially enemies, were gifts of sacrifice given to Odin. And thus the approach of Hugin and Munin on the battlefield meant that Odin was ready to accept his gifts (of death).

Interestingly, beyond themes of death and carnage, ravens are pretty intelligent creatures. This also deeply associated the ravens with the wisdom aspect of Odin. In that regard, the very word Huginn is derived from hugr or ‘thought’. So, in many ways, rather than mere pets, stories describe Hugin and Munin as extensions of the god himself.

Some have hypothesized that the ravens were the intellectual and spiritual components of Odin – who were detached from the one (or oneself) to curiously gather even more knowledge and wisdom. One stanza from the poem Grímnismál also mentions how Odin worries about the ravens not returning to him. This alludes to the dangerous gamble of ‘dividing’ oneself mentally and spiritually, especially when in a trance-like state of shamanism (or seiðr).

Huldra

Another creature from Germanic and Norse folklore, the Huldra (or Hulder) is represented as a fair and rather seductive female being who resides deep inside the forests. As such, the Huldra, also called skogsrå, may have been related to the guardian spirits of Norse mythology.

But over time, the Huldra was portrayed as a malevolent being, who while showcasing its apparent beauty and slenderness, lured young men to the dens deep inside the forest. And as is often the case in myths around the world, ultimately such men met their demise at the hand of the creature – that tended to reveal its true form of hideousness.

Interestingly, while performing its acts of seduction, the Huldra is said to have its unnatural cow’s (or fox’s) tail hanging from its dress. This did give the potential victim the opportunity to identify the imminent danger and turn away from the forest path.

Jormungand

Jormungand (or Jörmungandr) literally translates to the ‘Great Beast’. In Norse mythology, the massive monster, also known as the ‘World Serpent’ or ‘Midgard Serpent’ was one of the three offsprings of Loki and the giantess Angbroda (the others being Fenrir – the giant wolf, and Hel – the ruler of the Underworld).

In terms of depiction, Jormungand was believed to be so massive that the serpent (or dragon) encircled the entirety of our visible world (Midgard). In fact, by virtue of his humongous nature, Jormungand was even prophesized to bite (or grip) his own tail after growing large enough to surround the whole world.

And talking of prophecies, Jormungand was also foretold to encounter Thor at the Ragnarök – where both would slay each other. To that end, in the Eddas, it is even mentioned how Thor tried to fish for the giant serpent – who was initially thrown into the very depths of the seas by Odin to prevent a cataclysmic clash. But the fishing line, with its ox head’s bait, was severed by the giant Hymir, so as to postpone the ominous events of Ragnarok.

In the historical scope, the concept of Jormungand (or a giant monster residing in the depths of the earth) was prevalent in pre-Viking era Germanic societies. Even early medieval Germans attributed natural phenomena like earthquakes to the creature’s movements.

Jötnar

The Jötnar (plural form of jötunn) were supernatural beings who inhabited Jötunheimr (Jotunheim), one of the Nine Worlds of Norse mythology. Now in conventional terms, the jötnar are often conflated with typical giants, including the frost giants and fire giants. Consequently, in popular culture, they are projected rather negatively as typical enemies of the Aesir gods.

However, in traditional myths, the term jötnar was used in an extensive way, thereby referring to a race of beings (in contrast to a specific physical trait) who came in different shapes and sizes. For example, the jötunn Gerdr is described as being divinely beautiful, and her lovely shimmering looks even caught the attention of Vanir god Freyr – the deity of fertility (and ruler of elven homeland Alfheim).

Furthermore, some of the jötnar also play a crucial role in forging relations with the gods – so much so that most of the Aesir gods were actually descendants of the jötunn (via Bestia, who was the mother of Odin). On the other hand, there were also monstrous and frightful jötnar – like the giant wolf Fenrir and the humongous serpent Jormungand.

Some myths, including that of the Eddas, put forth the jötnar as having varied powers that were similar in vein to that of the gods. Quite intriguingly, the evil, monstrous, and even mentally stunted jötnar were also equated with creatures like trolls (discussed later in the article), giants (þurs), and demons.

Kraken

One of the monstrous creatures that originated in Scandinavian folklore, the Kraken can be perceived as the amalgamation of different legends and general romanticism associated with the unknown depths of the seas. In its most popular form, the Kraken is usually depicted as a cephalopod-like monster (or gigantic squid) that is so big that it can drag down an entire ship with its viciously large tentacles.

To that end, historians and researchers have often hypothesized that Krakens were possibly inspired by the real-life giant squids rarely sighted by the sailors of ancient and early medieval times. For example, in Norway, the legend of the Kraken as a giant squid was further reinforced when people began to witness the washed-up rotted specimens of these large cephalopods on the beaches.

Some of the carcasses were reinterpreted as sea devils or even sea monks. Furthermore, there was also the influence of aquatic monsters from other myths, like that of the Charybdis and Scylla from Greek mythology. The former was said to have the power to create an enormous whirlpool that could suck in ships and sailors alike.

Mares

Not to be confused with a female horse, the Old English word mare (or mara in Old Norse) means ‘monster’ or ‘goblin’. It is derived from mære, ultimately coming from Proto-Germanic maron meaning ‘goblin’ (its PIE root is mora- ‘incubus’). To that end, the term ‘nightmare’, originating from the early 14th century, used to mean ‘an evil spirit, sometimes female (incubus), that afflicted men in their sleep’ – thus corresponding to bad dreams.

For example, in the 13th-century Ynglinga saga, the king of Uppsala is suffocated by a mare ‘riding’ on his chest and head. Similarly, in the Eyrbyggja saga, a sorceress takes the form of a marlíðendr (‘night-rider’), which can be similar to a mare, to cause trample injuries to a character.

Quite incredibly, the first element of the name of the Celtic Irish goddess Morrigain (Morrigan) is possibly also derived from maron. To that end, in modern Irish, her name Mór-Ríoghain roughly translates to the ‘phantom queen’. Befitting this cryptic epithet, in the mythical narrative, Morrigan was capable of shapeshifting (who usually transformed into a crow – the badb) and foretelling doom, while also inciting men into a war frenzy.

Mokkurkalfi

Mokkurkalfi (or Mist Calf) was a gargantuan monster made of clay by the frost giants in Norse mythology. According to the story, the construct was made so as to frighten Thor – who was supposed to have a duel of combat with Hrungnir, the mightiest of the giants (jötnar). Simply put, the 9-mile tall, clay-made construct was to aid the giants in the ensuing fight with the thunder god.

And while Hrungnir was unceremoniously defeated and slain by Thor, the Mokkurkalfi was still at large. One version of the myth even mentions how Thor apparently wet himself at the sight of the lumbering monstrous construct whose head rose above the clouds. However, fortunately for the Aesir, Thor’s human servant Thjalfi (or Þjálfi) was less impressed by the clay-made construct.

He noticed the abrupt halting steps of the artificial giant and consequently swung his ax at the thick legs of Mokkurkalfi. As a result, the hulking yet ungainly construct toppled back and crashed to the ground. And such was its immense girth that its fall even resulted in an earthquake in Jotunheim – the homeworld of the jötnar(giants).

Nidhogg

Nidhogg (or Níðhöggr – meaning ‘curse striker’) was the dragon-like creature who gnawed away at the very roots of the Yggdrasil – the World Tree (the tree that held the various worlds of the Norse cosmos). In Norse mythology, Nidhogg was the primary malefactor among the many serpents and giants; and as such, his name meant – ‘he who strikes with malice’.

Simply put, Nidhogg was viewed as the eternal antagonist of the Norse mythos whose very intent was to let loose the forces of chaos into the realms of gods and men. In the poem Völuspá, Nidhogg is mentioned to rise (or fly out) from underneath the World Tree to (presumably) aid the jötnar and ‘devourers’ in their fight against the Aesir during the Ragnarok.

In the historical scheme of things, Nidhogg was possibly the personification of the ever-present evil or chaotic force that seemed to affect and influence humans. To that end, in the pre-Christian Germanic society, being called a nīðing (nīþ is the first syllable of Níðhöggr) was one of the worse forms of insult – so much so that the insulted person could even challenge the instigator in a deadly combat duel or take his words back.

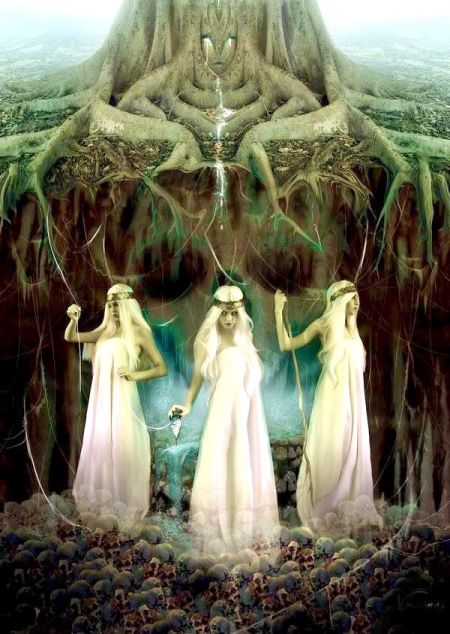

The Norns

The Norns (Nornir)are an interesting class of female mythical beings within Norse mythology who are often described as having the power to weave and even control fate. In essence, they were viewed as powerful entities (in some cases even more than gods), albeit a bit detached from the traditional framework of the cosmos.

Interestingly, in the Eddic poem, Fáfnismál (“Fáfnir’s sayings”), the Norns are represented as many in number, who came from different ‘races’ – including gods, elves, and even dwarves. However, the poem Völuspá describes the Norns as more mysterious beings who didn’t originate from any particular background. However, described as a trio, the three Norns Urd, Verdandi, and Skuld had the incredible power to respectively weave fate (sometimes related to the past), the present, and the future.

The poem further mentions how the three Norns resided underneath Yggdrasil, the cosmic tree that holds the universe and its realms. Their expanded role also included the caretaking of the tree – which they did by carrying water and fertile earth from the verdant well Urðarbrunnr.

Ratatoskr

Till now, we have talked about the undead, dragons, giants, and elves. However, Norse mythology also had its fair share of whimsical yet potent characters. One of them was the Ratatoskr (‘bore-tooth’) – a seemingly innocuous squirrel who ran messages (and insults) across the World Tree from Veðrfölnir, the wise eagle to Nidhogg, the serpent (discussed earlier).

In the Eddas, Ratatoskr, in spite of his small stature, was represented as a particularly mischievous creature who reveled in the insults exchanged between the eagle who was perched on top of the tree and the serpent who gnawed at its roots. At times, the squirrel twisted the words and made the nasty exchanges even more vitriolic – thus alluding to how the creature loved the gossip and bitter fallout associated with it.

Historically, Ratatoskr may have symbolized the ever-present general dangers to the world that go beyond the domains of chaos and order. Some have also theorized that the squirrel’s ultimate goal was to bring down the Yggdrasil – a feat that was only possible through purposeful malice rather than raw strength.

Sleipnir

Sleipnir (meaning ‘the slipper’) was the famed eight-legged horse of Odin, the chief of the Aesir gods. In Norse mythology, he was the son of the celestial stallion Svadilfari (or Svaðilfari -who was a jötunn) and a mare (that Loki shapeshifted into). In most narratives, Sleipnir is described as a great horse of Odin whose dimensions are so large that his gallop could alter the landscape of the area.

In other myths, Sleipnir is projected as being swift (rather than large) whose eight legs could carry his rider to all the nine worlds of the cosmos in a jiffy. And given his pedigree that combined a giant’s strength and a god’s divinity, Sleipnir also had the ability to bypass the natural boundaries of most realms.

For example, in the tragic tale of god Baldr’s death, his brother Hermóðr rode Sleipnir all the way to Hel, the realm of the dead. And the supernatural horse effectively jumped the fence of the underworld and even brought back Hermóðr safely to Asgard. In another story, Sleipnir was pitted against Gullfaxi, a swift horse owned by Hrungnir the giant (see the entry – Mokkurkalfi).

Tanngnost and Tanngrisnir

As opposed to popular cultural notions about the regal means of Norse deities, Thor’s very own chariot was actually pulled by two goats instead of great steeds (aptly showcased in the latest movie adaptation of Thor). Named Tanngnjóstr (“one that grinds teeth”) and Tanngrisnir (“one that has gaps in teeth”), the goats, incredibly, served the dual purpose of pulling the chariot and also serving as the god’s food.

The latter relates to how Thor cooked them when in need of sustenance. However, they were once again resurrected by Thor’s hammer – the magical Mjollnir. To that end, in one of the stories, Thor even shared his divine meat with human farmers. But their son Thjalfi (or Þjálfi) unwittingly sucked the marrow out of one of the goat’s bones (possibly tricked by Loki). This resulted in the goat’s lameness once the animal was resurrected.

As a form of reparation, Thjalfi was taken as a servant of Thor – and he later paid his dues by defeating Mokkurkalfi, the massive clay construct (discussed earlier). On another note, the resurrection of the goats also mirrors the fate of Sæhrímnir – the beast (or boar) that was cooked every night to feed the fallen warriors (einherjar) of Valhalla (hall of the slain) and was then resurrected once again on the following day.

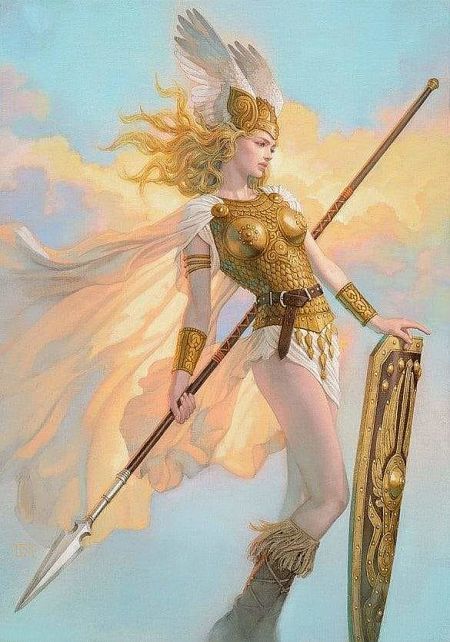

Valkyrie

Valkyries (or valkyrjur – meaning ‘choosers of the slain’) were Odin’s female spirits who aided the Norse god in bearing the dead warriors (or slain heroes of battles – known as einherjar) to the halls of Valhalla. Often depicted as elegant maidens, the Valkyries were also known to ‘earmark’ the warriors who would gain passage to the haloed halls of Odin after their death.

Now interestingly, while many Norse sources and their modern interpretations represent the Valkyries as noble female spirits imbued with beauty and power, the original Germanic narratives tended to portray them in a more portentous manner. One particular Skaldic poem Darraðarljóð shares such a view by describing how the Valkyries anticipatedly weaved the terrible fate of many Norse warriors at the famous Battle of Clontarf, circa 1014 CE.

The spirits weaved them in apparent glee, with terrifying elements like intestines and severed heads. Even the Anglo-Saxon version of the Valkyries, known as wælcyrie, were usually spirits associated with violence and death. Another school of thought hypothesizes how the Valkyries in Norse mythology was possibly an extension of the brutal power of Odin.

Honorable Mention – Trolls

In Norse mythology, the word ‘troll’ (or trǫll)didn’t really define any specific type of creature. Instead, the noun troll was used as a blanket term for various types of monsters, including fiends, demons, and jötnar (giants).

Sometimes also categorized as ‘thurs’ (or þurs) and risi (heroic beings), these trolls were commonly portrayed in a rather negative light – as unlikeable and even mischievous creatures of Norse mythology. Over the passage of time, the confusing and vague descriptions led to the categorization of ‘ugly trolls’ as ungainly, brutish, and dim-witted creatures who lived in isolation in the mountains and caves.

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork, or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "20 Fascinating Creatures of Norse Mythology"