Introduction

When it comes to the historically rich region of Mesopotamia, Babylon is arguably the most renowned of all cities. An ancient settlement that harks back to the dominions of Sargon of Akkad (circa 24th century BC), Babylon possibly started out as a small town in the backdrop of mighty cities like Ur, Uruk, and Nippur.

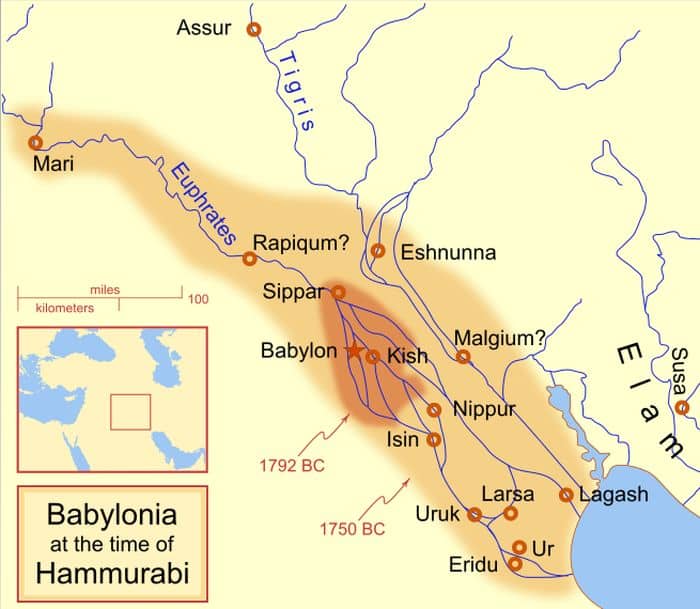

However, by the time of the ascension of Hammurabi the Great (the sixth king of the Amorite dynasty) in 1792 BC, Babylon became the major capital of the city-state of ‘Babylonia’, known as Mât Akkadî or ‘the country of Akkad’ in contemporary Akkadian.

The very term ‘Babylon’ is of Greek origin and it is possibly a rough translation of Babillu (or bav-ilim in Akkadian)– which in Semitic pertains to the conjunction of two words Bâb (gate) and ili (gods), thus suggesting the location of Babylon as the ‘gate of the Gods’.

On the Biblical side of affairs, Babylon is presented with a rather critical narrative. And arguably the most popular of these presentations pertains to the Book of Genesis, chapter 11, which deals with the infamous Tower of Babel – an architectural edifice that angers God, thus leading to the ‘curse’ of different languages of humanity, thereby mirroring the confusion and strife between cultures.

Ironically, the rather critical Biblical emphasis on Babylon is what attracted historians and archaeologists in the first place to find this ‘fabled’ city – ultimately resulting in its discovery in 1899 by Robert Koldewey.

Contents

The ‘Lost’ Years and Early Ascendance of Babylon (circa 24th – 17th century BC)

Some historians have hypothesized that Babylon as a settlement (by the Euphrates River) was possibly established sometime in circa 24th century BC, before the reign of Sargon of Akkad – the founder of one of the first known all-Mesopotamian empires that existed for around 180 years (while a few ancient sources even claim Sargon as being the founder of Babylon itself).

On the other hand, a few scholars have put forth their notion about how Babylon was founded by the ‘barbarian’ Semitic-speaking, semi-nomadic Martu (better known as Amorites) after the fall of the last Sumerian kings during circa 21st century BC.

In any case, the known history and ascendance of Babylon as an important city comes from the period (circa 1792 BC) that corresponded to the reign of Hammurabi, a relatively unknown Amorite prince who carved the first Babylonian city-state centered around the alluvial plain between the Tigris and the Euphrates.

Hammurabi burst into the political scene of Babylon by not only succeeding his father Sin-Muballit (who was probably forced to abdicate) but also continuing his father’s legacy in upgrading the city state’s infrastructure. Such massive projects ranged from enlarging and heightening the walls of the city, and building expansive canals, to constructing ostentatious temples in honor of his patron gods.

As a matter of fact, Hammurabi’s patronage of extensive infrastructural endeavors earned him the title of bani matim or the ‘builder of the land’.

However, beyond just popular civic projects, Hammurabi was a very ambitious ruler who long coveted the proximate lands of the resource-rich Mesopotamia. And after decades, guided by an opportunistic political drive and rather sophisticated military expeditions, Hammurabi was successful in becoming the master of the entire southern part of Mesopotamia – an enviable feat since he (possibly) started with only around 50 sq miles of land under his rule.

In the following years, he conducted campaigns against the rival (and very powerful) city-state of Mari in Syria; and by 1761 BC, entirely destroyed the city. And by 1755 BC, he directly marched onto Ashur and conquered Assyria, thus becoming the ruler of the entire Mesopotamia.

Consequently, the acquisition of various lands, cities, and their different social constitutions might have prompted the initiation of the Code of Hammurabi – a ‘universal’ law system that could rigorously deal with the divisive nature of the now-expanded Babylonian Empire.

Babylon’s Loss of Political Independence (circa 16th – 7th century BC)

However, from the perspective of history, it should be noted that Babylonia as an empire was soon eclipsed after the death of Hammurabi, with the realm being consequently annexed by the Hittites (who even sacked the city of Babylon in 1595 BC) and then Kassites.

Finally, the war-hardened Assyrians came to the fore and claimed the city by the early 8th century BC. All of these conquests, targeted toward the city, do however prove the importance of Babylon to the proximate invaders of the region, a pattern aptly demonstrated by the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal of Nineveh, who besieged and took the settlement (after a rebellion) and yet left it unharmed.

The king even took the trouble to personally ‘purify’ Babylon from the evil spirits, thus justifying the royal city’s status as a place of culture and learning. Subsequently, many Assyrian rulers treated Babylon as a ‘cultural’ capital and advocated their inclination towards Babylonian civilization, institutions, and science.

That was until King Sennacherib unceremoniously sacked the city in 689 BC, an act that was criticized by many contemporary people as a ‘rift between heaven and earth’, including nobles of his own court. Subsequently, many of the disfranchised and deported population of the city were only allowed to return after eleven years.

The Second Rise of Babylon (circa 7th century – 6th century BC)

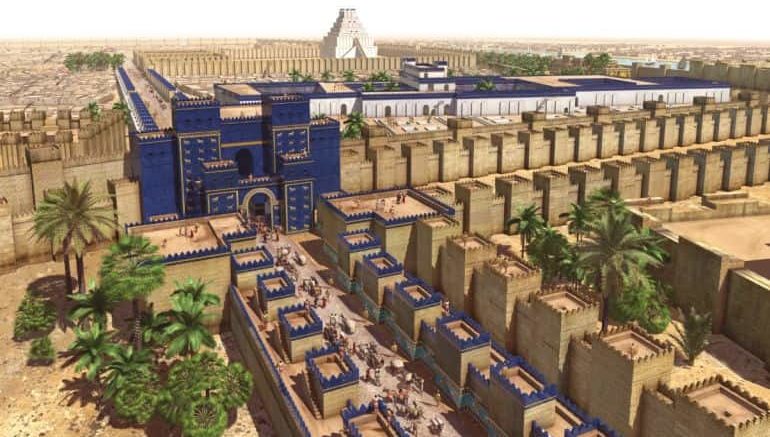

The video above presumably reconstructs the royal city of Babylon at its architectural peak during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar circa 6th century BC. And while the animation does flaunt a bevy of gorgeous 3D rendering techniques, it SHOULD BE NOTED that the creators have taken some artistic license to demonstrate the grandeur of Babylon. Few of these ‘anachronistic’ examples would relate to the dressing style of the inhabitants (which seems more akin to later Arab styles) and the portraiture of Achaemenid Persian motifs on some walls.

Like a phoenix rising from its ashes, it was a native soldier named Nabopolassar who was destined to expel his Assyrian overlords and restore the glory of the royal city of Babylon in 626 BC. Thus the Neo-Babylonian empire was founded, and the city reached its architectural peak under Nabopolassar’s son – Nebuchadnezzar II, who reigned from 605 to 562 BC.

Forever attracting the ire of Biblical writers for his alleged role in destroying Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem (see the 3D reconstruction here), Nebuchadnezzar II was also responsible for undertaking and renovating massive infrastructural and monumental projects inside the city of Babylon. The capital by then covered 900 hectares (2,200 acres) of land and boasted some of the most imposing and majestic structures in all of Mesopotamia.

The architectural list included the completion of the royal palace (supposedly inlaid with ‘bronze, gold, silver, rare and precious stones’), an entire stone bridge that connected the two major parts of the city over the Euphrates, the famed blue Ištar Gate, and the possible restoration of Etemenanki (‘House of the foundation of heaven on earth’) – a towering ziggurat (that has often been likened to the Biblical Tower of Babel).

In fact, the fully refurbished Etemenanki would have been one of the tallest man-made structures from ancient times, with its imposing height reaching around 298 ft or 91 m. Intriguing enough, a few ancient authors had also ascribed the construction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon – one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, to Nebuchadnezzar. However, recent studies have revealed how this landscaped masterpiece was possibly located in the city of Nineveh.

South of the Etemenanki, the Esagila was constructed as a massive temple complex dedicated to Marduk. This particular deity was by far the most important Babylonian god, with his worship almost bordering on monotheism. And incredibly enough, from the religiopolitical angle, Marduk, as opposed to many other gods, was said to reign directly from his stronghold Esagila in Babylon.

This symbolic significance rather bolstered the extension of the actual Esagila complex, which was completed in its final form by Nebuchadnezzar II, circa the 6th century BC. As a matter of fact, Marduk as a deity was held in such high regard in the lands of Babylonia that even ‘foreign’ Persian (Achaemenid) emperors like Cyrus and Darius projected themselves as the “chosen of the god”.

The Decline and Fall of Babylon (circa 6th century BC – 7th century AD)

This fascinating reconstruction (above) with some authentic depictions was made for the Mesopotamia exhibition of the Royal Ontario Museum, by the folks over at kadingirra.com.

The resurgence of the Neo-Babylonian Empire was snuffed out by the Persians under Cyrus the Great, with Babylon being captured after the Battle of Opis in 539 BC. According to most ancient sources, after defeating the Babylonian army in a few engagements, the Achaemenid Persian army made its triumphant yet bloodless entry into the jewel of the ancient world, the city of Babylon.

The task was made easy by the enemy tyrant Nabonidus, who fled the capital. Given such a ‘docile’ state of affairs, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Babylon, while losing its royal status, continued to flourish as a center of art and education under the Persians.

The cultural flair of the city was disparately interrupted by foreign pressure tactics, like an unexpected act from Xerxes that led to the destruction of Marduk’s solid gold statue (that was supposedly taller than the combined height of three men) in a bid to fill up the royal exchequer.

This desperate action was taken in reaction to riots fermenting inside Babylon. However, the awe with which Babylon was perceived in the ancient world remained intact even after the Persian Empire was conquered by Alexander the Great. As historian Stephen Bertman wrote –

Before his death, Alexander the Great ordered the superstructure of Babylon’s ziggurat pulled down in order that it might be rebuilt with greater splendor. But he never lived to bring his project to completion. Over the centuries, its scattered bricks have been cannibalized by peasants to fulfill humbler dreams. All that is left of the fabled Tower of Babel is the bed of a swampy pond.

From Alexander’s death in 323 BC till the rise of the Parthians in 141 BC, Babylon certainly remained largely symbolic in its scope as the ‘last bastion’ of Mesopotamian culture in the Seleucid realm. Unfortunately, by the Common Era, the impressive settlement was all but forgotten, except for a brief revival under the Sassanids.

However, by the 7th century AD, the rampant socio-political changes in the region finally took their toll on Babylon, thereby relegating it to ruins during the advent of the Islamic civilization in what is now Iraq.

Online Sources: World History / Livius / Khan Academy / Live Science

Book Reference: The Cambridge Ancient History

Featured Image Source: DKFindOut

Be the first to comment on "Babylon: History and Reconstruction of the Ancient Mesopotamian City"