Introduction

Fashion and technology – while these words have vastly different connotations in our modern world, their combined scope in history was mostly related to warfare. That is because warfare in itself (at least till late medieval history) was dominated by the kings, nobles, and elites of the society. These wealthy groups had access to both fashionable items and technological progression, a fusion of which coalesced into intricate armor systems for better protection (and thus the chance of survival) on the battlefield. So without further ado, let us take a gander at 12 marvelous warrior armor ensembles from history you should know about.

Contents

- Introduction

- Mycenaean Dendra Panoply (circa 15th century BC)

- Persian Immortal Armor (6th – 5th century BC)

- Roman Lorica Segmentata (late 1st century BC – 3rd century AD)

- Sassanid Savaran Armor (4th – 7th century AD)

- Eastern Roman Cataphract ( Kataphraktoi ) Armor (7th – 10th century AD)

- Samurai Ō-yoroi (circa post 10th century – 15th century AD)

- Siculo-Norman Knight Armor (circa 12th century AD)

- Mongol Keshik Armor (13th – 14th century AD)

- Aztec Jaguar Warrior Armor (circa 14th – 16th century AD)

- Indian War Elephant Armor (15th – 17th century AD)

- German Landsknecht Dress (15th – 16th century AD)

- Polish Winged Hussar Armor (16th – 18th century AD)

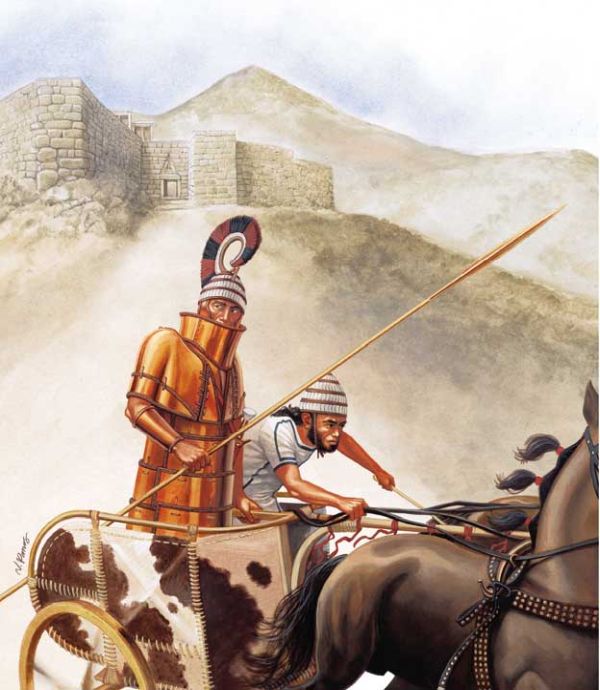

Mycenaean Dendra Panoply (circa 15th century BC)

The above-pictured armor is not a figment of the imagination of the illustrator but rather depicts the incredible specimen from Bronze Age, known as the Dendra panoply. Named so because of the discovery of the earliest of these fascinating specimens in the village of Dendra in the Argolid (see actual image here), the warrior armor system was developed from the late Mycenaean period (or at least after the 15th century BC) and probably used by the elite members of the Mycenaean army who rode into battle in chariots.

This uncovered specimen in question consists of fifteen separate sheets of beaten bronze that were fastened by leather bands. The main cuirass in itself comprised two different facades (for the front part and rear part of the torso) that were joined by a hinge.

Additionally, the impressive warrior armor ensemble boasted big shoulder guards, triangular arm-pit guards, a deep neck guard (composed of a high bronze collar), and even greaves (padded with linen). So after all these pieces were ‘set up’, the complete panoply equated to a robust, full-covered plated body armor that may have been imposing in its scope, though surely cumbersome in its usage.

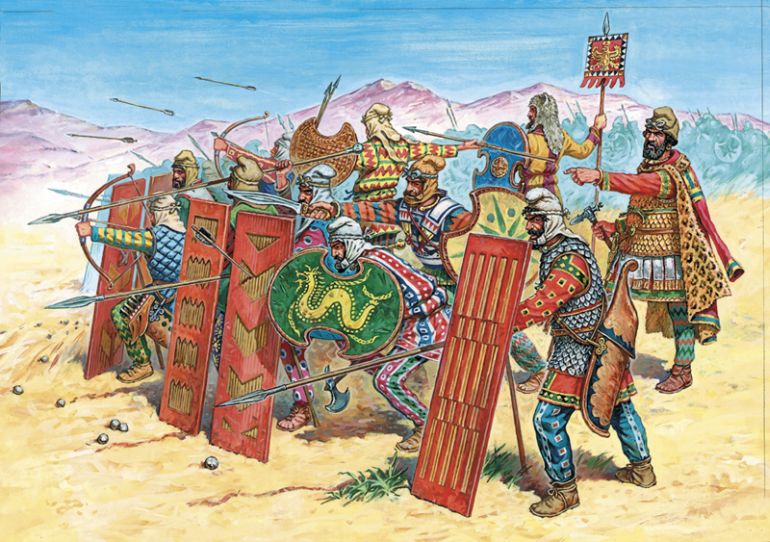

Persian Immortal Armor (6th – 5th century BC)

The ancient Persians almost had an obsession with the number ‘thousand’, and as such their regiments were theoretically divided into thousand men known as hazarabam (hazara denoting thousand). The decimal system was also upheld when ten such regiments were combined to form a division (baivarabam) of 10,000 men. The so-called ‘Immortals’ or Amrtaka (in Old Persian) was the chosen baivarabam of the Persian king, and their scope of ‘immortality’ seemingly stemmed from their constant number – which was always kept at 10,000 (according to Herodotus).

In other words, the casualties in this elite division might have been replaced as soon as possible by the best candidates from other Persian baivarabam. Herodotus also described the warrior armor of these crack troops of the Achaemenid Empire –

The dress of these troops consisted of the tiara, or soft felt cap, embroidered tunic with sleeves, a coat of mail looking like the scales of a fish, and trousers; for arms they carried light wicker shields, quivers slung below them, short spears, powerful bows with cane arrows, and short swords swinging from belts beside the right thigh.

As can be comprehended from such accounts, the Persian Immortals were probably very different from the oddly ‘dark’ manner in which they were depicted in the movie 300. As a matter of fact, such elite divisions tended to flaunt their vibrant and ritzy uniforms and armaments – as is evident from their accounts of carrying spears with golden pomegranates, silver pomegranates, and even golden apples. The latter-mentioned spears were carried by the king’s own bodyguard unit of 1,000 men – known as arstibara, but nicknamed the ‘Applebearers’.

Roman Lorica Segmentata (late 1st century BC – 3rd century AD)

The ubiquitous Lorica Segmentata is one of the tropes of ancient Rome, with its fair share of (often anachronistic) portrayals in popular culture. But beyond its familiarity and faux name (the very Latin term Lorica Segmentata was coined in the 16th century and literally translates to ‘armor in pieces’), the warrior armor design in itself was a testament to Roman ingenuity. Used after the 1st century BC till the 3rd century AD, thus corresponding to the apical period of the Roman Empire, the panoply combined the advantages of heavy protection offered by plate armor and flexibility due to its varying sections.

In terms of design, the armor was composed of metallic strips that were horizontally arranged in an overlapping manner in the downward direction. The ‘setup’ basically enclosed the torso in two halves, with fastenings both at the front and back. Additionally, the armor was reinforced by shoulder guards along with breast and back plates, thus accounting for the protection of the upper body and shoulders.

There were numerous modifications over the years (at least till the 3rd century) that rather improved upon the core bearing of the Lorica Segmentata, but historians are still not sure about the actual historical users of this segmented cuirass – with theories covering both legionaries (as depicted in Trajan’s Column) and auxilia (as evidenced by archaeological finds in Roman fort sites).

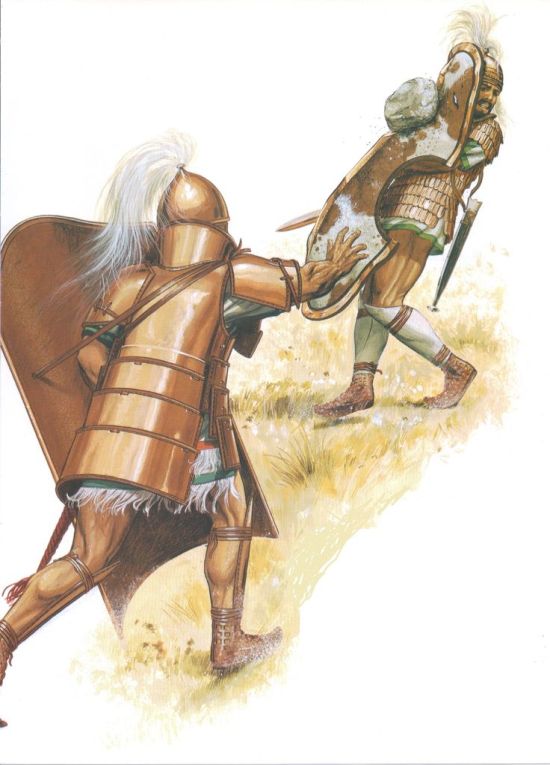

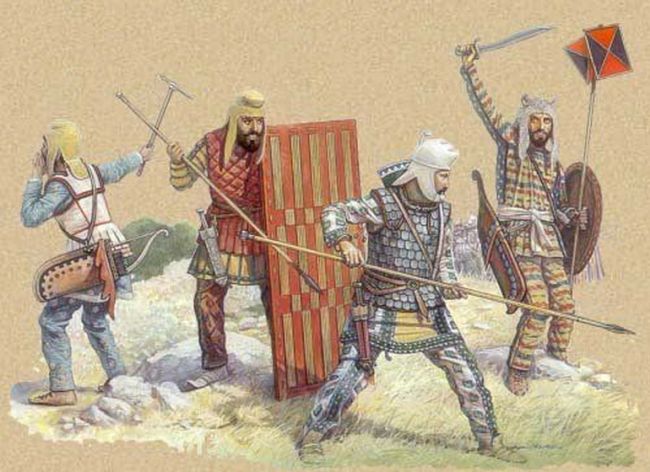

Sassanid Savaran Armor (4th – 7th century AD)

The (Persian) Sassanian society of antiquity held the Arteshtaran or warriors in high regard, and among them, the Savaran formed the elite cavalry corps of the empire with their own Drafsh (banner). To that end, the Savaran were mostly composed of members from the seven royal families of Persia, the upper nobility (known as the azadan), and also the lower nobility (under the Khosrow reforms), thus mirroring the knightly class of the later European middle ages.

In essence, the Savaran fulfilled the military role of heavy cavalry, partly inspired by the shock tactics of their predecessor Parthian cataphracts, while also taking up the societal role of a knight bound by feudal laws of the land.

In terms of their warrior armor, the Savaran knights had variations based on their divisions. For example, the Sassanid Zhayedan (Immortals) and Royal Pustighban (pictured above), comprising prestige units within the Savaran, were probably more heavily armored than their theoretical ‘peers’, and hence were only used as a reserve force to secure breakthroughs in a battle.

In any case, most Savaran knights tended to be well-armed (with lances, axes, maces, bows, and even whips) and armored, with typical accouterments ranging from lamellar, scale, laminated to mail. The latter type was often used in combination with vambraces and breastplates, while finally evolving into entire mail coats that often reached down to the knees, thus once again reflecting the style of the early European knights.

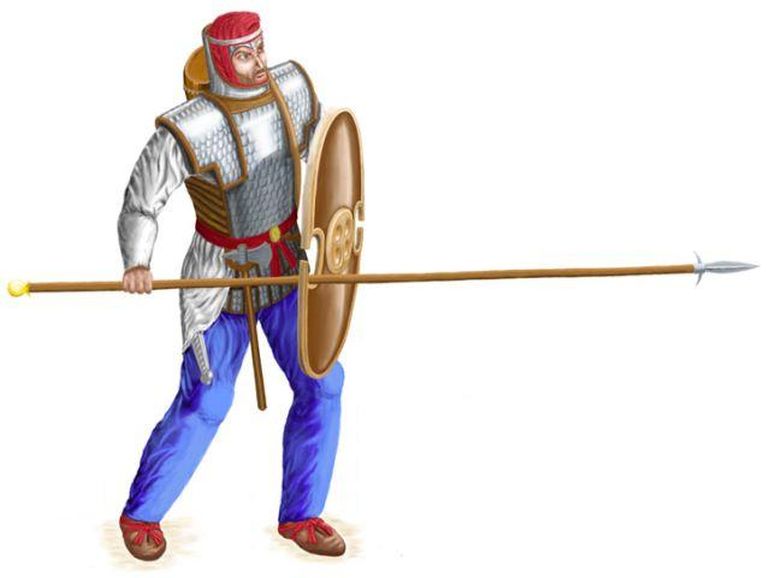

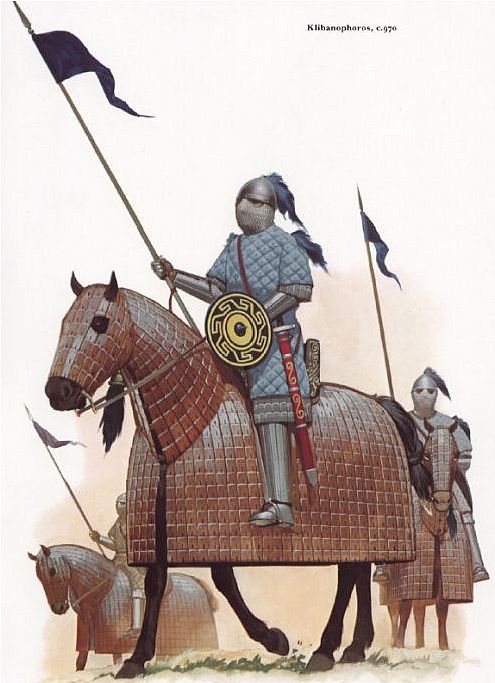

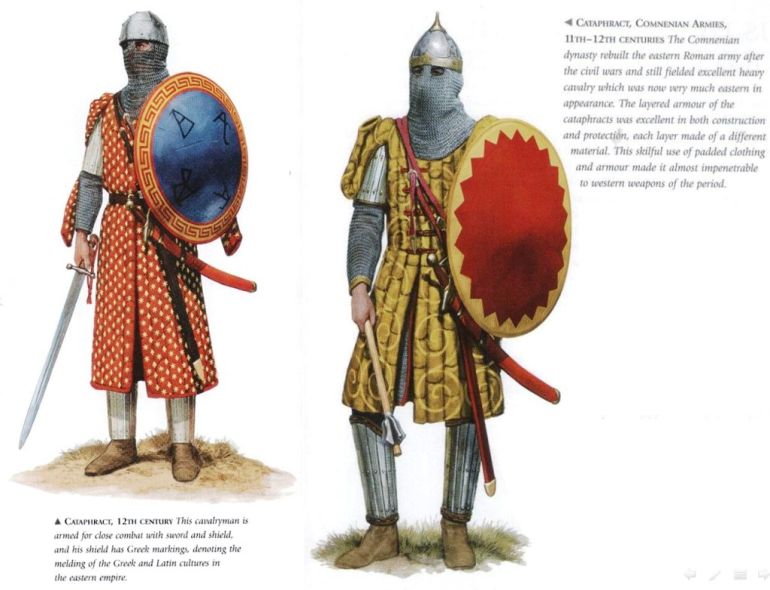

Eastern Roman Cataphract (Kataphraktoi) Armor (7th – 10th century AD)

The very term Cataphract (derived from Greek Kataphraktos – meaning ‘completely enclosed’ or ‘armored’) is historically used to denote a type of armored heavy cavalry that was originally used by ancient Iranian tribes, along with their nomadic and Eurasian brethren. To that end, the Eastern Romans adopted the cataphract-based mounted warfare from their eastern neighbors – the Parthians (and later Sassanid Persians), with the first units of the heavy cavalry being inducted into the Roman Empire army as mercenaries (probably raised from mounted Sarmatian auxiliaries).

And interestingly enough, the subsequent Byzantine army maintained its elite units of cataphracts from antiquity till the early middle ages, thus ironically carrying on the tradition of eastern equestrianism.

In any case, the Eastern Roman Cataphract of the Byzantine Empire fielded till the 10th century, was known for its super-heavy armor and weapons (that included maces and rarely even bows). Typical contemporary descriptions of the cavalrymen mention the use of klibanion, a type of Byzantine lamellar cuirass that was crafted of metal bits sewn on leather or cloth pieces.

This klibanion was often worn over a mail corselet, thus resulting in a heavy ‘composite’ armor, which was further reinforced by a padded armor worn under (or over) the corselet. This tremendously well-protected scope was complemented by other armor pieces, like vambraces, greaves, leather gauntlets, and even mail hoods that were attached to the helmet.

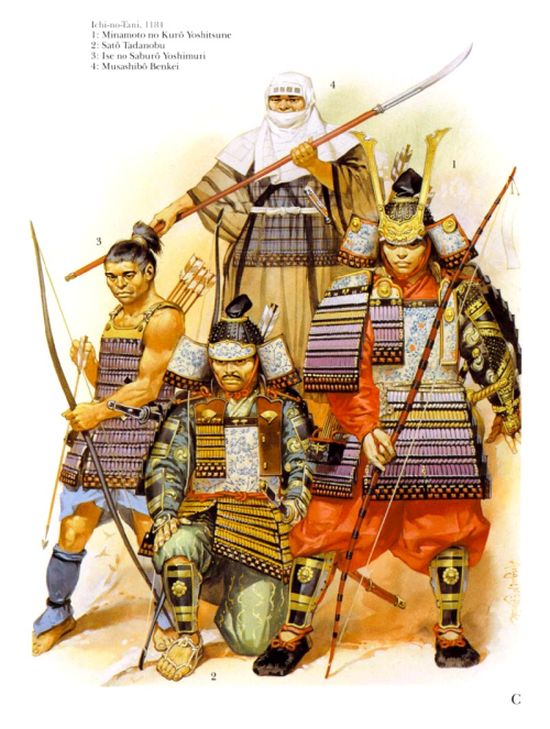

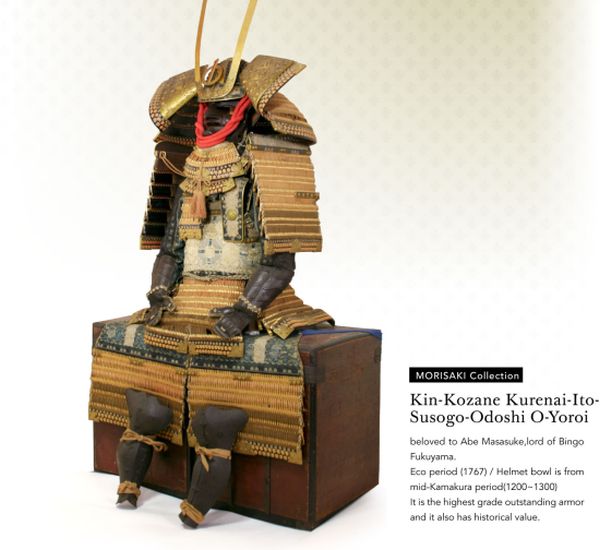

Samurai Ō-yoroi (circa post 10th century – 15th century AD)

The Ō-yoroi or ‘great armor’ was specifically designed for mounted archers, who often formed the elite forces of the Japanese Samurai. In essence, the great warrior armor was reserved for the high-ranking warriors (‘bushi‘), especially after the 10th century AD, when such elite troops performed the tactical tasks of cavalrymen and mobile archers on the battlefield. As an article from Boris Petrov Bedrosov (at myarmoury.com) describes –

The most distinctive feature of the o-yoroi was its cross-section, which had the form of the Latin letter “C”. A three-section cuirass fully protected the back, left, and front parts of the body, and only the right part (where the letter “C” is opened) was protected with a separate section called the waidate. The waidate was put on first and was tied to the body with two silk cords—one at the level of the waist and the other diagonally across the chest and over the left shoulder.

The straps (watagami) were strengthened with vertical, semi-rounded plates which protected the shoulders from vertical cutting strokes. The cuirass was closed with the traditional buttons (kohaze) attached to the watagami. These were made from hard wood, horn, and sometimes ivory. A copper ring (agemaki-no-kan) was riveted in the middle of the back section. To it, the heavy silk braid, butterfly-like knot called agemaki was tied.

In spite of such intricate arrangements within the Samurai warrior armor, the visually striking part of the o-yoroi arguably relates to its ‘leather’ finish. This printed leather was called the egawa, and one of its elements known as the tsurubashiri provided the ‘illusion’ of full-plate armor. This entire panoply, weighing over 65 lbs, was complemented by the mengu or facial armor that was either crafted from iron or lacquered leather.

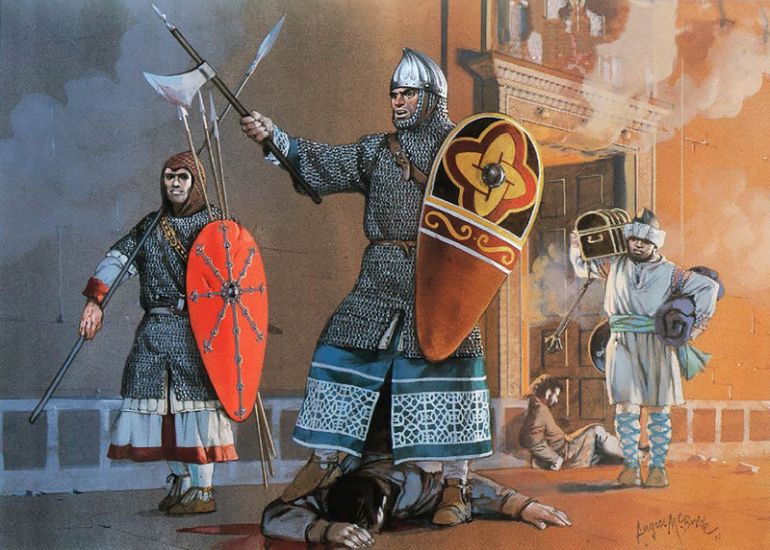

Siculo-Norman Knight Armor (circa 12th century AD)

The first bands of Norman mercenaries had started infiltrating the southern parts of Italy that were still under Eastern Roman rule, by 1017 AD. And after a steady trickle of settling and raiding, the preliminary military conquests were initiated by the famed Norman adventurer Robert Guiscard and his small party (which consisted of only five mounted riders and thirty followers on foot – according to Byzantine historian Anna Comnena) in 1041 AD.

Over the course of the next thirty years, many towns of southern Italy fell to Norman forces, thus effectively ending the influence of the Eastern Romans. This period also coincided with the repeated incursions and ultimate Norman conquest of the rich island of Sicily. This was a significant event in European history since the island with its dominant Christian population had been under the suzerainty of Arab rulers for more than 150 years.

But beyond just an event with religious implications, the subsequent formation of the Kingdom of Sicily resulted in a synergistic cultural domain that was seldom seen in the rest of ‘backward’ Western Europe. In fact, the ‘adaptable’ Norman rulers were thoroughly influenced by the previous Arabian cultural ambit, and as such even adopted many segments of Islamic traditions and styles, including some elements of their dress, language, and even literature.

The warrior armor of the late Siculo-Norman knight was a product of such cultural overlaps, with one of the major sources of visual information coming from the carved capital depictions of the cloister of Monreale Cathedral. One such portrayal harks back to a magnificently equipped Norman nobleman (knight) equipped in a partially gilded helmet with a face mask, complemented by a mail coif and a ritzy attire. Interestingly enough, the feet of his mail chausses were probably enclosed in iron scales, thus hinting at advanced craftsmanship for the contemporary age.

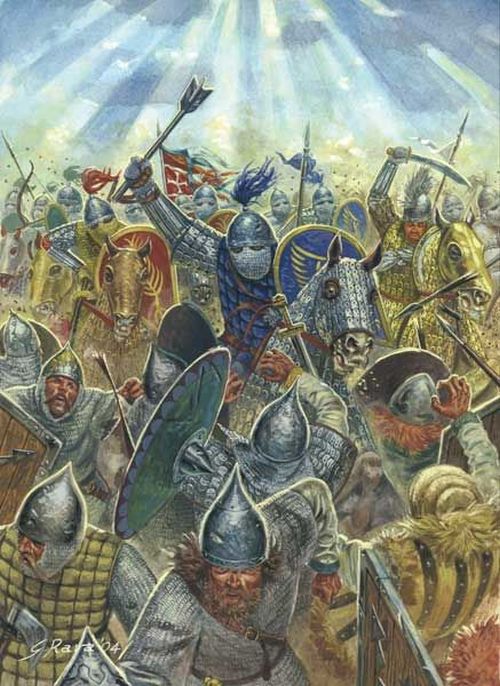

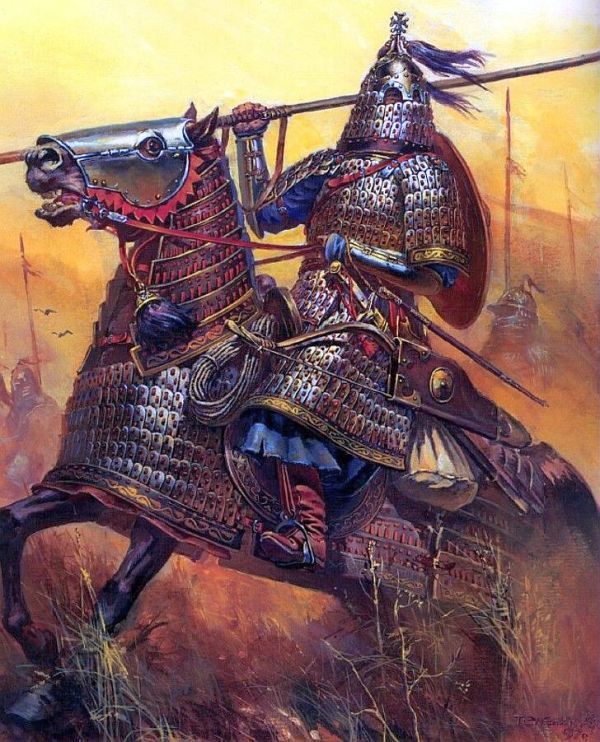

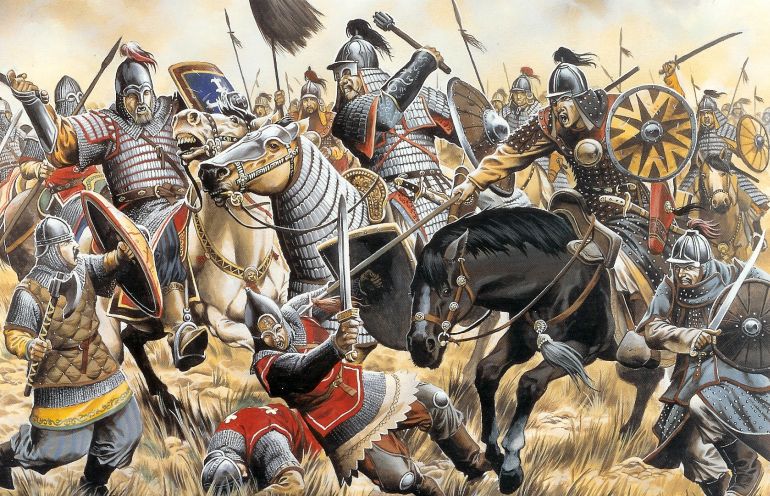

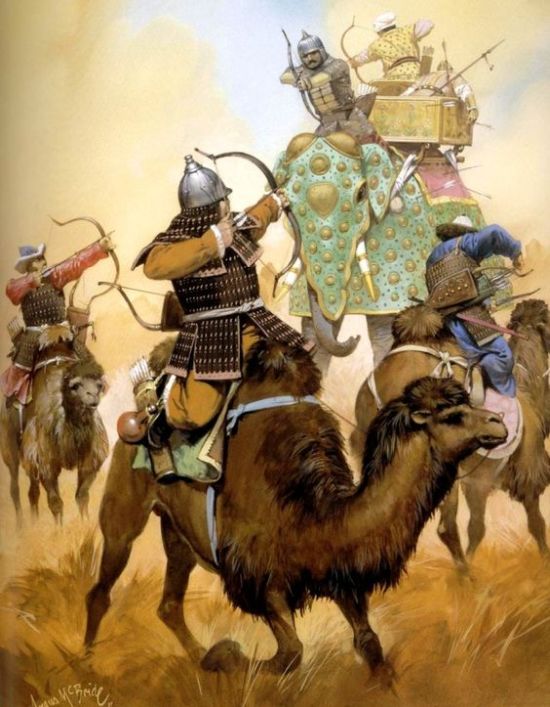

Mongol Keshik Armor (13th – 14th century AD)

Historically, the Mongol Keshik may have pertained to the chosen bodyguard for the royal families of the horde, corresponding to Genghis Khan’s time (later adopted by his successors). And while like most of their elite counterparts, the warrior armor of the Keshik evolved with time, the core characteristics of the style remained familiar with its basis on the lamellar arrangement of pieces.

According to Carpini’s description (John of Plano Carpini was possibly among the first Europeans to enter the court of the Great Khan), many of the Mongol heavy cavalrymen wore armor that was crafted from an array of tiny metal pieces that were bound together expertly by leather thongs. This particular panoply suggests the Asiatic composite type of armor with lamellar overlays.

The warrior armor was complemented by a helmet made of larger metal pieces with additional protective features like a neck guard (made of iron plates) and a separate lamellar armor for the hardy horse itself (in spite of being a smaller breed than its Arabian and European counterparts). Furthermore, interestingly enough, while this specific topic is debated, it is not unlikely that the elite cavalry forces of the Mongols wore silk shirts beneath their armor systems.

And the reason went far beyond vanity. This is because, as opposed to popular notions, most of the harm by penetrating arrows was caused when the arrowhead was pulled out of the skin. So a layer of silk might have come in handy with its fibers being twisted around the arrowhead, thus protecting (most of) the wound from the penetrative foreign object. Moreover, Mongols were probably aware of silk’s anti-bacterial properties when treated with dyes (or even turmeric). Obviously, this was not due to their perceived knowledge of the germ theory, but rather because of years of experience in warfare and wound treatment.

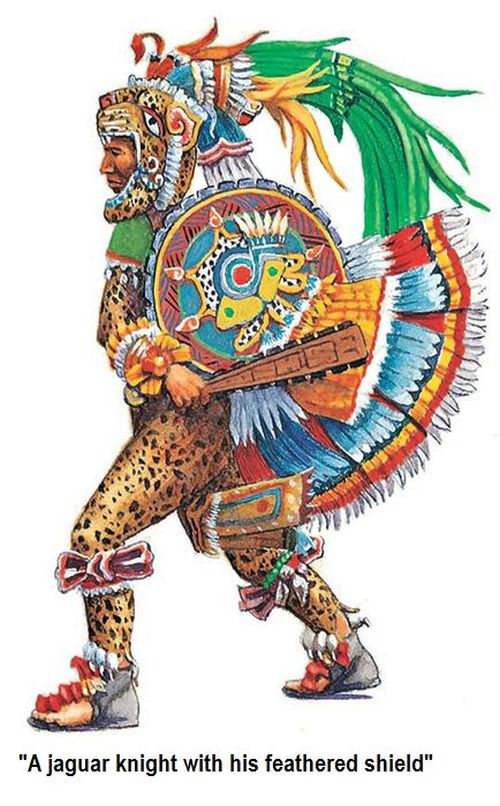

Aztec Jaguar Warrior Armor (circa 14th – 16th century AD)

A unit made famous by the real-time strategy game Age of Empires 2, the Jaguar Warriors belonged to the elite military order fielded by the Aztecs. Accompanied by their brethren – the Eagle Warriors, the Jaguar Warriors (known as ocēlōtl in classical Nahuatl) were chosen on the basis of their bravery and ability to capture enemy warriors (for later sacrifice), and thus were placed at the fore of their war band.

Interestingly enough, unlike many contemporary societies, this collective elite force, sometimes referred to as the cuāuhocēlōtl, was composed of members from both the nobility and the commoner class, which in itself suggests the importance of training, ferocity, and bravery in the Aztec society over class-based warfare. However, it should also be noted that most members of the Jaguar Warrior military order expected to be granted lands and titles by their lords, thus in many ways mirroring the knightly class of the medieval Europeans.

As for the warrior armor, the battle-hardened members of the elite Aztec military orders, including the Cuachicqueh (or ‘Shorn Ones’), were often dressed in regalia that matched their names. Suffice it to say, the Jaguar Warrior draped themselves in pelts of jaguars (pumas), a practice that not only enhanced their elevated visual impact but also pertained to a ritualistic angle wherein the warrior believed that he partly imbibed the strength of the predator animal.

It can be hypothesized that these elite warriors also wore a type of quilted cotton armor (known as ichcahuipilli) under their animal pelts while higher-ranking members tended to flaunt their additional apparel in the form of colored feathers and plumes. Such boisterous scopes of visual exhibitions were complemented by deadly weapons like the Macuahuitl (roughly translating to ‘hungry-wood’), a wooden sword with sharp obsidian blades drilled into its sides.

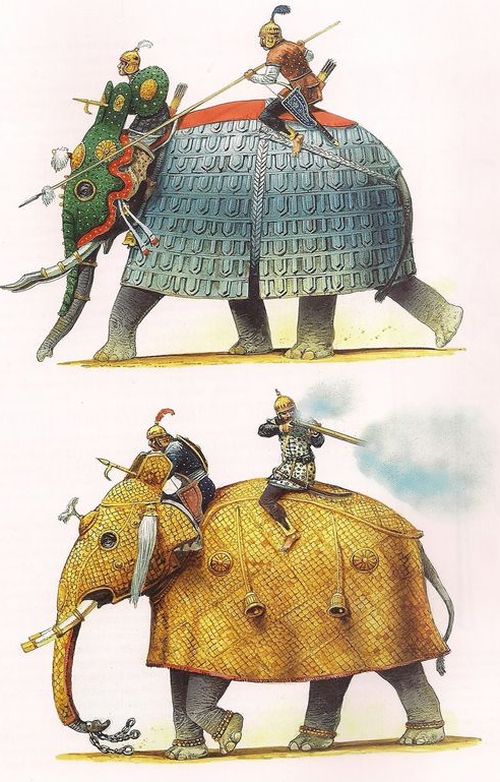

Indian War Elephant Armor (15th – 17th century AD)

Intriguingly, the first possible evidence of elephants being trained for war comes from China, during the period of the Shang Dynasty from 1600-1100 BC. And while wild Chinese elephants dwindled in numbers (and Mesopotamian elephants became extinct) circa 500 BC, the legacy of war elephants was carried forth by Indians, Persians, and subsequently the Greek successor states and even Carthaginians in the ancient times. However, the armored war elephants in question here hark back to the later medieval times of India, corresponding to the period between the 15th to 16th centuries, when the development of gunpowder weaponry was still in its relatively nascent stage.

To that end, the extensive armor system of these highly-valued war elephants (mostly comprising the male gender) consisted of intricately crafted face masks with strategic vision holes that protected the ears and trunk of the humongous animal. In fact, the exhibited War Elephant Armor at the Royal Armouries in Leeds has headgear so heavy that it requires three attendants to lift that particular section.

As for the main body armor in itself, the panoply was crafted from sheet iron panels and chainmail woven across cloth or leather. And like in the case of the earlier mentioned Cataphract warrior armor, this sturdy sheath was accompanied by a padded cloth or leather on the inside, to keep the animal (partly) comfortable.

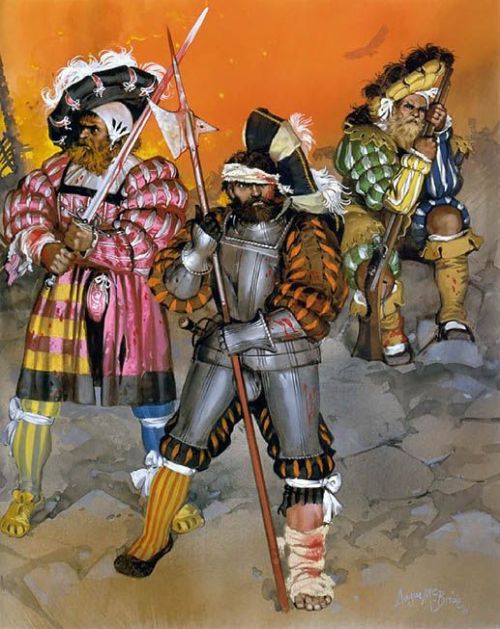

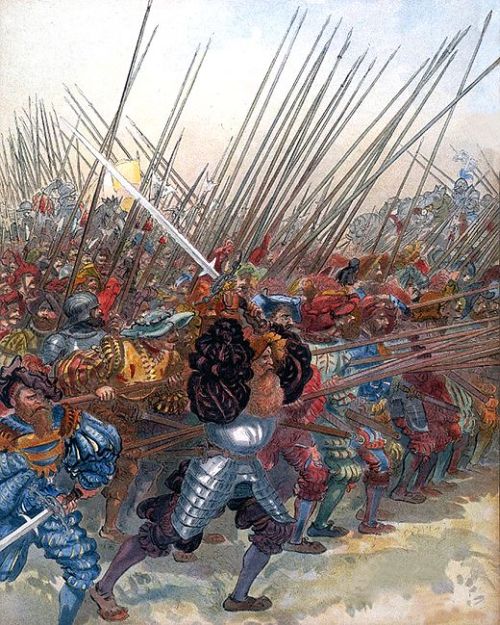

German Landsknecht Dress (15th – 16th century AD)

The very term Landsknecht, first coined in the late 15th century, translates to ‘servant of the country’. But while this term suggests a scope of humility, the Landsknechts were anything but modest, with their florid, colorful uniforms (often bordering on the gaudy), flamboyant caps, and penchant for violence and rambunctious pursuits.

Recruited as boisterous soldiers of fortune from mostly Germany, these medieval mercenaries possibly copied the weapons and tactics of the revered (and often expensive) Swiss Guards or reisläufer. At times, the rivalry between these two units reached vicious levels, especially when pitted against each other in battles where the quarter was neither asked for nor given – resulting in encounters known as schlechten krieg or ‘bad wars’.

In terms of warrior armor, the Landsknechts went rather light with simple breastplates with tassets (thigh guards) and steel skull caps, thus focusing on their offensive capabilities with weapons like pikes, halberds, and zweihänder (two-handed) swords. Such varied weapon types were accompanied by side-arms like katzbalger (cat skinner) swords with S-shaped quillons, crossbows, and later arquebuses.

However, what lacked in armor was more than made up for by their garish warrior attires that were worn to flout the medieval rules of decency. These loud costumes translated to slashed doublets, striped hose, and tight (or sometimes oversized) breeches – most of which were flaunted to showcase their privilege in being exempt from laws that dictated certain decorum in dresses during contemporary times.

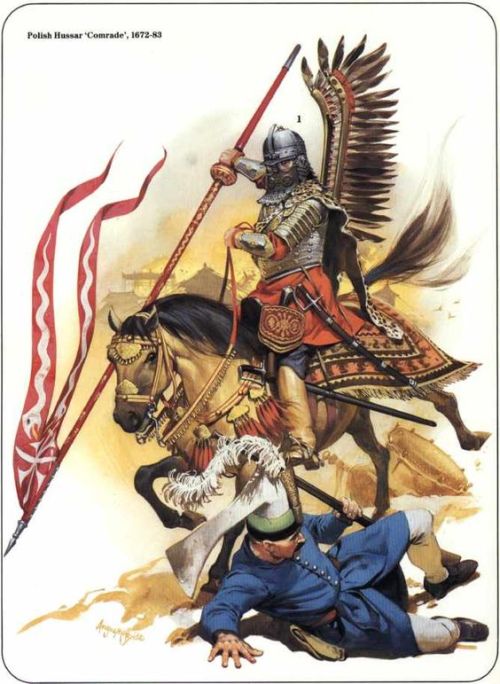

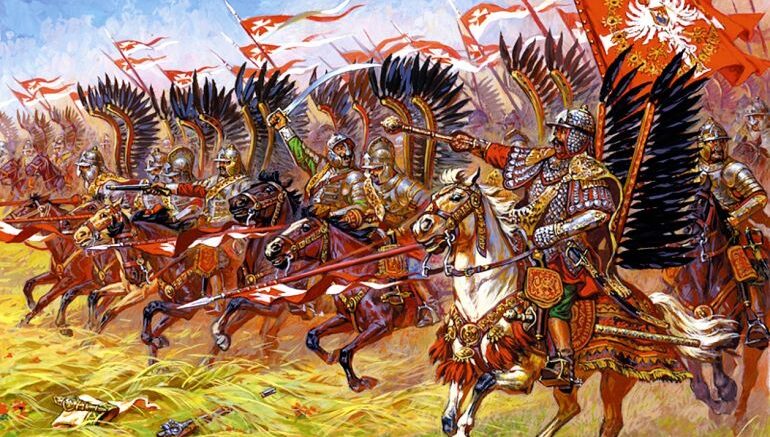

Polish Winged Hussar Armor (16th – 18th century AD)

While historically Hussars may have originated from the Serbian mercenaries who served as light cavalry in the 14th century, the Polish Winged Hussars epitomized the shock cavalry arm of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth between the 16th and 18th centuries. Showcasing their stylized yet heavily armored avatars, partly fueled by the mid-16th century reforms of Stephen Báthory (one of the most successful kings in Polish history), the winged hussars serving under their dedicated banners (chorągiew) were essentially the elite of the effective (and often victorious) armies of the thriving Eastern European commonwealth.

The ostentatious warrior armor of the 16th century Polish Winged Hussars was undoubtedly inspired by their earlier Hungarian counterparts, along with influence from some regions of western Europe – like the lobster-shaped anima breastplate that originated in Italy (and possibly in turn influenced by the ancient Roman Lorica Segmentata). However by the 17th century, when the warrior armor of this elite cavalry force was arguably at its most stylish stage, the inspiration was clearly borrowed from the East, rather than the West. The ornately burnished cuirasses were accompanied by helmets, mail sleeves, lances, koncerz swords, and even firearms (sclopetum or rudimentary pistol).

In any case, the unique feature of the winged hussar armor obviously related to the ‘winged’ part, and unfortunately, this is where history and legends combine to paint a rather unrealistic picture. From the archaeological perspective, experts know of the early wing types that were made by simply attaching rows of the feather into a straight batten. It can be hypothesized that during the reign of John Sobieski, these wings took more elegant forms with vibrant color schemes, possibly sourced from geese, eagles, and even vultures.

However, historians are not really sure about the actual purpose of these ornamental apparel. And while popular culture suggests how the elaborate feathers whistled their way into the thick of battle to terrify foes, (most) scholars believe that these wings were used to intimidate the opponents by sheer visual impact (complemented by the dazzling effect of the hussar warrior armor).

Book References: The Normans (By David Nicolle) / Mongol Warrior 1200-1350 (By Stephen Turnbull) / The Mycenaeans c. 1650-1100 BC (By Nicholas Grguric) / The Persian Army 560-330 BC (by Nicholas Sekunda) / Sassanian Elite Cavalry AD 224 – 642 (By Dr Kaveh Farrokh) / Polish Winged Hussar 1576-1775 (By Richard Brzezinski)

Be the first to comment on "12 Marvelous Warrior Armor Ensembles from History You Should Know About"