Though the extended weapon of the longbow precedes the medieval Englishman by over 3,500 years (with the first known specimen dating from 2665 BC), it was the renowned longbowman of the Middle Ages who made a mark on the tactical side of affairs when it came to famous military encounters.

And while Sluys (1340), Crécy (1346), Poitiers (1356), and Agincourt (1415) proved the prowess of the English longbowman, there was certainly more to the scope of being a dedicated archer in a military world dominated by heavily armored knights and men-at-arms. So without further ado, let us check out ten interesting facts that you should know about the English longbowman.

Contents

- Not All English Longbowmen Were ‘English’

- The ‘Indentured’ Retainers and the Yeomen

- Monetary Matters and Plundering

- Training (Or Lack Thereof)

- Armor and Arms Supplied by the ‘Contract’

- The Actual Longbow

- Design and Range of the Longbow

- Bracers For Safety

- The ‘Harbingers’

- Battle of Agincourt – A Victory Against Overwhelming Odds

- Honorable Mention – The Cry of ‘Havoc’

Not All English Longbowmen Were ‘English’

The common misconception about the English longbowman actually pertains to his categorization as being sole ‘English’. Now while the tactical aptitude of the longbowman flourished after the 14th century, the origins of archery-based warfare in Britain had a far older tradition. To that end, during the late 11th century Anglo-Norman invasions of Wales, the Welshmen gave a good account of themselves in archery against their well-armored foes.

Interestingly enough, the Normans were probably inspired by the tactical acumen of the natives. And given their penchant for adaptability, the bow was raised to be a prestigious weapon after the Norman conquest of England. Practicality (obviously) played its role alongside ceremonious affairs – with the bow achieving its ‘prestige’ solely due to its sheer effectiveness in the hand of specialized archers who defended northern England from the encroaches of the lightly-armored Scots.

As a result, the English armies continued to employ Welshmen as dedicated archers. But even more antithetically, the English also employed Frenchmen in their ranks. Now from the historical perspective, this shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise.

That is because, by the 13th-14th century, the English Plantagenet monarchs continued to hold vast tracts of land and settlements in continental France. So many French people from these parts (like the Gascons and French-Normans) often viewed the English as their overlords and thus served in their armies (including archery divisions) without compunction.

The ‘Indentured’ Retainers and the Yeomen

According to historian Clive Bartlett, the English armies of the 14th century, including the longbowmen, mainly comprised the levy and the so-called ‘indentured retinue’. The latter category entailed a sort-of contract between the King and his nobles that allowed the monarch to call upon the retainers of the noblemen for purposes of wars (especially overseas).

This pseudo-feudal arrangement fueled a class of semi-professional soldiers who were mostly inhabitants from around the estates of the lords and the kings. And among these retainers, the most skilled were the longbowmen of the household. The archers from the King’s own household were termed the ‘Yeomen of the Crown’, and they were rightly considered the elite even among the experienced archers.

The other retainers came from the neighborhoods of the great estates, usually consisting of followers (if not residents) of the lord’s household. Interestingly enough, many of them served the same purpose and received similar benefits as household retainers.

There was also a third category of the retainer longbowman, and this group pertained to men who were hired for specific military duties, including garrisoning and defending ‘overseas’ French towns. Unfortunately, in spite of their professional status, these hired retainers often turned to banditry, since official payments were not always delivered on time.

Monetary Matters and Plundering

Oddly enough, in the early 14th century, both the levied archers and the retainers were paid the same amount (of 3 pence a day) in both England and France – in spite of their presumed difference in skill levels. However, by the 15th century, there were many changes in the military laws, with a notable one relating to how the raised levies could only serve in the ‘domestic’ arenas, like England and (in some cases) Scotland.

On the other hand, the retainer English longbowman groups bore the brunt of the fighting in ‘overseas’ France, thus endowing them with a professional character. Their improved pay scale also reflected such a change, with the new figure being 6 pence a day – adding up to around 9 pounds per year. In a practical scope, the number actually came down to around 5 pounds per year; and for comparison’s sake, a medieval knight required around 40 pounds per year to support himself and his panoply.

Naturally, it begs the question – why did the retainer longbowmen agree to their ‘indentured contracts’ in spite of such low wages? Well, like in the case of the Mongols, the monetary benefit didn’t come from wages, but rather from various ‘perks’. For example, some household retainers were paid yearly annuities by their lords, and these sums frequently went into double figures. Others were gifted houses and monetary bonuses.

And lastly, there was the age-old attraction towards plunder and ransoms. Regarding the latter, high-ranking prisoners of war were immediately handed over to the captain, and consequently, the longbowman was paid a healthy reward. While in cases of low-ranking victims, the captor could directly demand his ransom.

The resultant money (if paid) was then distributed in accordance with some set rules. Two-thirds of the sum could be taken by the captor (the longbowman), while the remaining one-third was divided among the captain, his superior commander, and ultimately the king.

Training (Or Lack Thereof)

Training specifically for warfare and battlefield tactics, or at least what we understand as rigorous training for warfare (aka boot camp), was notably absent from the itinerary of an English longbowman. So why was the longbowman considered potent, especially in the latter half of the 14th century? Well, the answer lies in their skill level, rather than their physical aptitude for battles.

Simply put, there was a tradition of archery among both the retainer and levied folks, with skill sets passed down through generations. So while most of them didn’t train specifically for battle scenarios, they did practice their archery skills for recreational and hunting pursuits.

In fact, some English monarchs banked on this ‘exclusivity’ of longbow-based archery skills that gave their armies an edge over other contemporary European forces (usually comprising crossbowmen) – so much so that numerous statutes were passed that obligated many retainers to practice their archery on Sundays.

There were also regular instructions from the royal court that wholesomely encouraged people to take up archery. As King Edward III’s declaration of 1363, makes it clear (as referenced in the English Longbowman: 1330 – 1515 by Clive Bartlett) –

Whereas the people of our realm, rich and poor alike, were accustomed formerly in their games to practice archery – whence by God’s help, it is well known that high honor and profit came to our realm, and no small advantage to ourselves in our warlike enterprises…that every man in the same country, if he is able-bodied, shall, upon holidays, make use, in his games, of bows and arrows…and so learn and practice archery.

However, it should be noted that by the middle of the 15th century, the longbowmen were not considered as deadly as they were some decades ago. Contemporary chronicler Philip de Commynes talked about how the Englishmen in Charles the Bold’s army were not worthy of actual battlefield maneuvers.

As a counter to the decreasing standards of the longbowmen, the Duke of Burgundy may have also trained these folks in shooting volleys when combined with the pikemen, thus hinting at the precursor to pike-and-shot formations.

Armor and Arms Supplied by the ‘Contract’

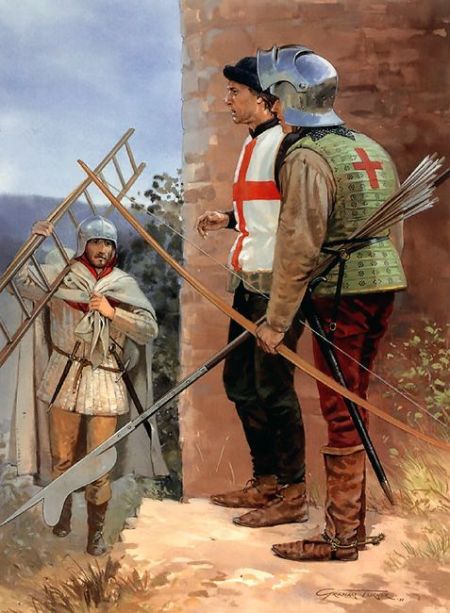

As opposed to the ill-equipped European archer of the early medieval times, the longbowman was furnished with armor and arms that were provided by his employer (the lord or the king). According to a household accounting book of 1480 AD, a typical English longbowman was protected by brigandine – which was a type of canvas (or leather) armor reinforced with small steel plates riveted to the fabric.

He was also issued a pair of splints for arm defenses, a ‘sallet’ (a war helmet or a steel-reinforced cap), a ‘standart’ (or ‘standard’ that protected his neck), a ‘jaket’ (basically his livery), a ‘gusset’ (which could have been either synthetic underwear or a small plate the protected his joints), and a sheaf of arrows. Presumably, much of such equipment was kept in stock and was only issued by the senior commanders in times of war.

The Actual Longbow

Contrary to some notions, the longbow was not the only kind of bow used by English archers after the 14th century. In fact, most of the archers used their personal bows for hunting and occasional practice. But after they were retained (or levied), the men were supplied with newer war bows by the aforementioned contract system (or the state). These new longbows pertained more or less to a standard issue, and thus their mass-scale production became easier to manage.

Now the longbow was not actually the most efficient projectile-based weapon of its time. However, the design made up for its difficulty of usage through other means – like its relative cheapness and simplicity when compared to the crossbow.

Furthermore, the longbow in the hand of an experienced longbowman packed quite a punch with its capacity to even puncture (early-period) steel armor over a substantial distance. This is what Gerald of Wales, the Cambro-Norman archdeacon, and historian of the 12th century, had to say about the Welsh longbow (the precursor to the ‘English’ variety), as sourced from the English Longbowman: 1330 – 1515 (By Clive Bartlett) –

…[I]n the war against the Welsh, one of the men of arms was struck by an arrow shot at him by a Welshman. It went right through his thigh, high up, where it was protected inside and outside the leg by his iron chausses, and then through the skirt of his leather tunic; next it penetrated that part of the saddle which is called the alva or seat; and finally it lodged in his horse, driving so deep that it killed the animal.

Design and Range of the Longbow

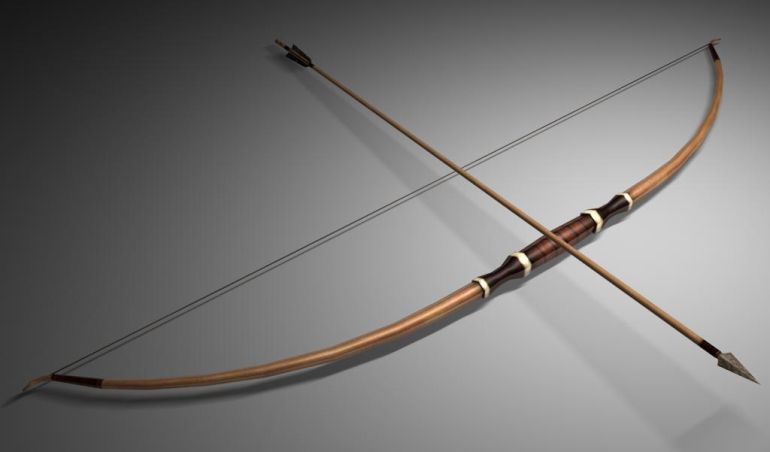

Unlike composite bows, the longbow used for wars was usually crafted from a single piece of wood, thus alluding to the simplicity of its design. In that regard, the preferred timber had always been of the yew variety, though seasonal changes and availability dictated the use of other wood types too – like ash and elm. To that end, the mass production of longbows was fairly regulated by the state (and the lords), with dedicated tree plantations specifically supplying many of the required staves.

There were also times when England had to import yew bow staves from continental European realms, namely Venice and other Italian states. In any case, most of the bow staves were frequently assessed and sorted out for quality by specially appointed officials; while a longbow in itself could be furnished from a prime stave in under two hours by the expert bowyers, thus fueling an impressive rate of production.

Historian Clive Bartlett has talked about how the finished longbow (often painted and sometimes ‘whitened’) was over 6 ft (or 6 ft 2 inches), though even longer specimens (up to 6 ft 11 inches) have been discovered from the wreck of the famous 16th century Royal Navy warship Mary Rose.

Now in terms of optimized shape, the members (limbs) of the bow should appertain to the round ‘D’ shape. This scope of physicality translated to around 80-120 lbs of draw weight, though higher draw weights of up to 185 lbs were used in battles – which made the draw lengths go over 30 inches.

And finally, when it came to the range, there are no particular contemporary sources that accurately portray the figures during medieval times. However modern reconstructions (of even the Mary Rose specimens) have sufficiently proven that longbows could acquire ranges of somewhere between 250-330 m (or 273 to 361 yards).

All of these factors of force and range, when combined, were enough to penetrate Damascus mail armor; though plate armors were still relatively undamaged. But it should also be noted that the ‘bodkin’ arrows shot by the longbowman could potentially account for blunt trauma on heavily armored horsemen (like knights) since these riders already possessed the added forward momentum of their galloping war horses.

Bracers For Safety

The extended scope of the longbow along with the taut nature of the string (usually made from hemp) surely transformed the craft into a dangerous weapon to handle. The main danger to the user was due to the string hitting the forearm area in its ‘backlash’. This could be avoided by either bending the elbow or adjusting the distance between the string and the bow when strung – but both of these measures hampered the intrinsic shooting range and technique of the longbowman.

So as a solution, the longbowman opted for bracers (forearm armor) that were crafted from leather and horn (and even from walrus tooth ‘ivory’ on rarer occasions). Generally exhibiting a strap-and-buckle system, as evidenced by the extant specimens salvaged from Mary Rose, the bracers also carried some form of insignia. These heraldic devices probably showcased the city origin of the archer or the lord’s badge under whose command the longbowman served.

The ‘Harbingers’

The ‘Harbinger’ by definition pertains to a forerunner or herald who announces or signals the approach of another. However, in practical terms, the English ‘Harbingers’ of medieval times served a tad different purpose. Attached to the logistical corps of the army, they were tasked with finding the billets of the ordinary soldiers and longbowmen before the arrival of the main body of troops.

These billets were fairly well arranged in English soil, with the quarters being allocated in accordance to the rank and influence of the soldier; though in France, the method sometimes gave way to madness – with chaotic affairs and strong-arming deciding the good habitation scopes.

Interestingly, the Harbingers (sometimes having longbowman divisions in their ranks) also served as scouts who looked for the dry sites conducive to camping that had access to essential requirements like wood and water.

Battle of Agincourt – A Victory Against Overwhelming Odds

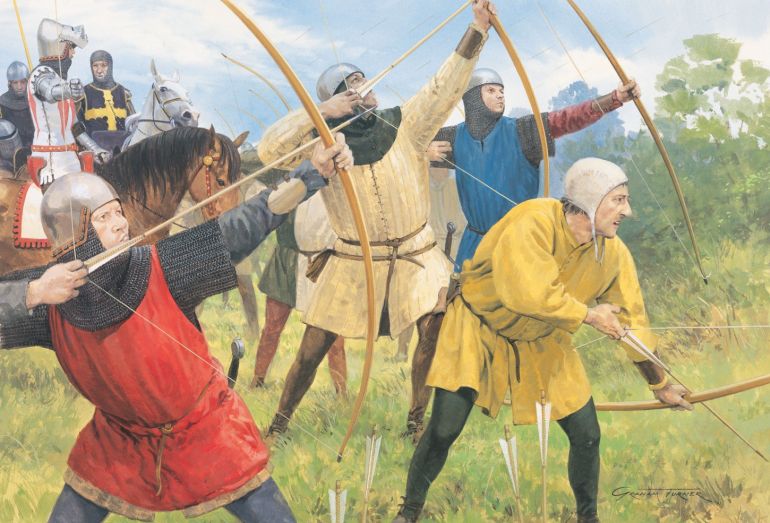

In many ways, this renowned engagement from the Hundred Years War demonstrated the superiority of tactics, topography, and disciplined archers over just heavy armor – factors that were obviously rare during the first decades of the 15th century.

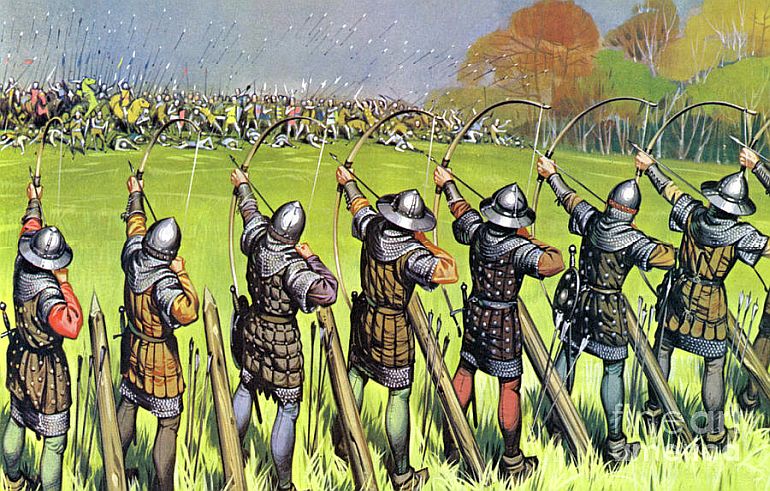

As for the battle itself, it pitted around 6,000 to 9,000 English soldiers (with 5/6th of them being longbowmen) against 20,000 to 30,000 French forces, who had around 10,000 heavy armored knights and men-at-arms. The haughty mindset of the French nobility participating in the battle could be somewhat gathered from chronicler Edmond de Dyntner’s statement – “ten French nobles against one English”, which totally discounted the ‘military value’ of a longbowman from the English army.

As for tactical placement, the English army commanded by Henry V, the King of England, placed itself at the end of a recently plowed land, with their flanks covered by dense woodlands (that practically made side cavalry charges nigh impossible). The front sections of the archers were also protected by pointed wooden flanks and palings that would have discouraged frontal cavalry charges.

But in all of these, the terrain proved to be the greatest obstacle for the armored French army, since the field was already muddy with recent occurrences of heavy rain. In a twist of irony, the armor weight of the French knights (for at least some of them) became their biggest disadvantage, with the mass of packed soldiers fumbling and stumbling across the soggy landscape – making them easy pickings for the well-trained longbowmen.

And, when the knights finally reached the English lines, they were utterly exhausted, while also having no room to effectively wield their heavy weapons. The English longbowmen and men-at-arms still nimble-footed, switched to mallets and hammers – and delivered a crushing blow in hand-to-hand combat on the frazzled Frenchmen.

In the end, it is estimated that around 7,000 to 10,000 French soldiers were killed (among them there were around a thousand senior noblemen). And even more were taken prisoners, while the English losses were around the paltry figure of 400.

Honorable Mention – The Cry of ‘Havoc’

While William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar made the phrase famous, the cry of ‘havoc‘ was actually a call used during medieval times by the English (and Anglo-French) armies to signal the beginning of plundering. In essence, ‘havoc’ (or havok, derived from Old French havot, meaning pillaging) heralded the end of a victorious battle, and thus the war cry was taken pretty seriously by the commanders. In fact, it was taken so seriously that even a premature call of ‘havoc’ during the battle often resulted in the death penalty (by beheading) for the ones who started the cry.

Now while this may seem harsh, such rigorous punishments were part of the military regulations of the late 14th century. Many of them were formulated for the ‘practicality’ of instilling discipline in the army – a quality that often decided the outcome of a battle; a case in point pertaining to the Battle of Agincourt.

Furthermore, unlike the boisterous French nobles of the time, the English took collective precautions for their relatively smaller armies, thus upholding the principles of safety. So in essence, the premature ‘havoc’ callers might have run afoul of such principles, which could have put the entire army in danger when pillaging in their unguarded ‘mode’.

Book References: English Longbowman: 1330 – 1515 (By Clive Bartlett) / Longbowmen, Tactics, and Terrain: Three Battle Narratives from the Hundred Years War (By Molly Helen Donohue)

Online Sources: Journal of the Society of Archer-Antiquaries / ThoughtCo / Longbow-Archers / BritishBattles

Be the first to comment on "The English Longbowman: 10 Things You Should Know"